Читать книгу Hillcountry Warriors - Johnny Neil Smith - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

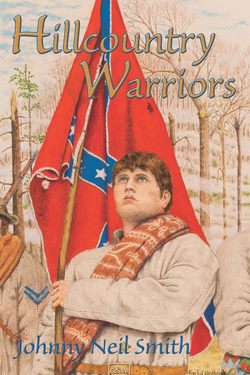

COONTAIL

ОглавлениеBy 1850, drastic changes transformed the forest lands of Newton county into many thriving communities. Large stands of virgin pine and hardwoods still sheltered most of this land, but where ancient, majestic trees had once stood like sentries guarding their fellow comrades, now open fields of grain, log cabins, and split rail fences were emerging. Where paths made by the Choctaws once weaved themselves through the entanglement of swamp bottom reeds and canes and twisted endlessly into the open forest, roads wide enough to allow wagons to pass now crisscrossed the county like a huge spider web and where vast herds of deer had once roamed at will, cattle, sheep, hogs and horses now grazed in the same open fields and meadows. The wilderness was gone.

By 1850, Little Rock was growing and prosperous. Thomas Walker’s general store and mill was thriving and he also sold lots to others who built a blacksmith shop, a livery stable and a tannery. One structure the entire community deeply valued and appreciated was its United Church. People of several protestant faiths came together to build this first edifice in the eastern section of Newton County. Each group only met once a month on its designated Sunday for its own worship. It was also in this church that people came together to discuss problems and have fellowship with one other. They also took great pride in organizing a school which was held in the building. All children in the community were invited to attend and most took advantage of the offer whenever they could be excused from their farm chores.

Lott and Sarah now had six children, but of the six, two died as infants; one during delivery and another of typhoid fever when only a few months old. Of the remaining four, the first three were boys and their last a girl.

Their eldest son, James Earl born in 1839, was a sickly child who suffered from asthma and could not stand the long and tiring days in the field. But, he could take care of livestock and gained a reputation as the most knowledgeable person in the community. People from all parts of the county would come to talk with him about problems they were having with their cattle and horses.

The second son, Thomas Stanley, was born in 1841. He was strong and energetic and much like his Uncle Jake; he grew into a large boisterous man who never met a stranger but had difficulty controlling his temper. Thomas loved working in the fields with his father and often would keep at it after his father called it quits. At times when they were behind and the moon was full, he would remain in the field with the company of only the night creatures.

The third child, born in 1845, was called John Lewis. He became a versatile young man loved and respected by all in the community. Like Thomas, he was strong enough to stay in the fields and could work along with his father and Thomas on an equal basis. He also liked helping James Earl with the livestock and horses and became fascinated with horse racing. What made him different from his brothers was his intense desire for education. His ambition to become a lawyer and judge drove him to hours of reading late into the night.

Finally in 1847, Sarah bore the girl she had wanted and needed for so long. Mary Lucretia was the prize of the family. Sarah, Lott and the boys all loved and overprotected her. In fact, she was so spoiled she considered herself the most important member of the family and felt her every wish should be fulfilled. But she was quick to learn and, like John, valued her education at the First United Academy.

Jake and Hatta were not so fortunate. Once while Jake was shoeing one of his racehorses, a spirited mare kicked him in the groin, seriously injuring him. It took months to recover, and the injury put an end to their additional family expectations.

Jake had wanted a house full of children, so he gave Homer his full attention and love often to the point of neglecting his wife.

It was now 1850, and fall was in the air. The Wilsons were almost done with their harvesting of cotton, corn, and wheat. Work was beginning to slow down so the families could spend more leisure time together and the men had time to venture into the woods to hunt squirrels, rabbits and raccoons.

One of the family treats was a Saturday afternoon ride visiting neighbors. This gave the children a chance to play with each other, a chance they seldom saw during the summer and early fall months due to their farm work. The excursion always ended at Walker’s store where the family would purchase supplies for the next week, see if any mail had arrived and watch the arrival of the four o’clock stage from Meridian.

It was just such an afternoon as this, when the family pulled up to the front of Walker’s store. Before the wagon had come to a complete stop, the children bounded out of the back and scrambled up the steps to see who would be the first to ask about the mail.

“Lott, Hatta and me is going to step up the road a piece to visit Mrs. Walker and Rebecca. You come get us when you want to go home. Okay?” Sarah said, as she began walking toward the Walker’s house.

“That’s fine. Me and Jake got a few things to do and we’re going to sit the stage out,” answered Lott. “Jake, you need any help with them jugs?”

“Naw, there ain’t but about twenty of ’em,” replied Jake who was already making his way up the steps with two jugs in each hand and one under each arm.

“Walker, you in there? Get yore back door open, and let me store some of this precious water ‘fore I decide to drink it,” laughed Jake.

“Yeah, come on in. I been waitin’ for ya,” Mister Walker said, holding the door open and giving him a low bow as Jake struggled to work his way through the narrow opening. “Jake, you know folks ain’t hittin’ the jug as heavy as they used to. I think religion’s gettin’ to them. Preacher Jones laid a sermon on us last Sunday ‘bout the evils of liquor, and he even made me feel guilty,” stated Mister Walker.

“Hell, Walker, you can’t believe everything a preacher says. We had one in Savannah that could drink you and me under the table,” replied Jake, as he headed out toward the wagon to get another load.

He stopped at the door, paused as if in deep thought, and turned to share his revelation. “You let a preacher show me in the Bible where it says you can’t drink liquor. He can’t. It says you just don’t overdo it, don’t drink in excess. That’s in Matthew 20:14. Walker, them preachers going to ruin this community.”

“Jake! Get out here. I want to show you sump’n,” Lott said who had been sitting on a bench on the front porch of the store, but was now standing and staring down the street toward the blacksmith’s shop.

“What’s got you in a stir, Big Brother? I ain’t seen you this disturbed since you chunked that piece of wood at me.”

“Jake, you see that wagon down there. It had a bunch of Negroes in it, and one looked like that Toby from back then.”

“So what. I don’t see nothin’ and so what if’n it is?” answered Jake disappointed that Lott’s excitement was only about a wagon load of Negroes.

“Jake, there ain’t s’pose to be no slaves ‘round here and Toby ought to be in Louisiana. I’m goin’ down there and see what’s goin’ on.”

“Damn Lott, you know you just a busybody. You know there’s some slaves here’bouts, and I heard ole Frank was bringin’ them in to work his fields. You ain’t going to stop slavery here,” Jake said, trying to catch up with his brother.

Reaching the wagon, Lott could see five Negroes inside preparing to load a box of plow heads and Toby was among them.

“Toby, that you ain’t it?” questioned Lott, pushing the door open so he could get a better look. “What ya still doin’ here in Coon Tail?”

“Yessuh, it’s me and I lives here now. Master Ollivah done brought me back. It’s been a long time since I see’d you Wilsons. You need sump’n?”

“Naw, we don’t need nothin’. We just meddlin’, that’s all,” replied Jake, bored with Lott’s questioning.

“Toby, how many slaves Frank got down here?” continued Lott.

“I don’t rightly know, Mist’ Wilson. Maybe, twenty or so. I don’t knows ‘bout no countin’,” Toby said, uneasy about answering Lott’s questions.

“Twenty!” exclaimed Lott. “I knowed he was a no good scoundrel. I had a feelin’ he was going to do sump’n like this.”

Suddenly a large, heavyset man appeared from the back of the shop carrying a whip in one hand and a keg of powder under his arm. Jake recoiled recognizing the type of person approaching them. He had seen them in Savannah. This man was a slave overseer.

“You niggars get that wagon loaded ‘fore I takes the hide off yore back,” stated the man, ignoring the Wilsons. “We gotta get this gear back ‘fore dark.”

The man stepped up on the wagon wheel, settled himself on the seat and then stared directly at Lott. “I heard what you said ‘bout Mister Olliver, and I think it best you keep out of his affairs. These here niggars is slaves and it ain’t a damned thing you can do about it. I also know who you is and know yore reputation. I guess you is Lott and the big ugly one over there is Jake. Just remember the name Jason Talbert and if’n you is smart, you’ll stay out of my path and leave my niggars alone.

Jake had about all he could stand of Talbert and started walking toward the wagon.

“Man, I’ve had all yore mouth I can take. You need to be taught some manners,” Jake said, as he rushed over to the wagon.

Quickly, Talbert pulled a revolver from his coat and pointed it directly at Jake’s forehead.

“Lott Wilson, you get this idiot out of my way or I’ll blow his brains out in the streets,” warned Talbert.

Lott hurried over to Jake and pulled him back toward the livery stable.

“Jake, let’s just drop it. It ain’t worth you gettin’ shot over. I’m the one who started the whole thing.”

The wagon pulled away from the stables and headed south for the Olliver farm.

“Talbert!” shouted Jake, “this ain’t over. One day I’m going to show you how I dealt with yore sorts in Savannah.”

“I hear ya,” answered Talbert, the wagon now approaching Walker’s Store. “You just keep fightin’ with the boys, you ain’t ready for a man yet.”

The children came running from the store to see what was causing the commotion. Homer was the first to reach the street and almost ran in front of Talbert’s wagon.

He jerked the reigns quickly to the right to pull out of Homer’s path. He was surprised at what he saw. At sixteen, Homer was tall and handsome but did not resemble the other children of Scotch-Irish descent. His hair was golden but he had large brown eyes and reddish-brown skin. A most unusual boy.

“Boy! Or ever what you is. Keep the hell out of my horses’ way. Next time, I’ll just run over ya,” shouted Talbert, as he brought the horses under control and quickly made his way out of town.

“What’d that man say to ya, Son?” questioned Jake, as he embraced and comforted him.

For several moments, Homer could say nothing but finally mumbled, Tm all right, Papa. He just scairt me a little. I’ll be fine. I don’t like that man. He’s got too much hate in his eyes.”

“Lott, let’s get the chill’un and women and go on home. I don’t feel like waitin’ for the stage,” Jake said.

“This has ruined my afternoon, too,” answered Lott who had slumped on the store steps to calm himself.

John ran up to the Walker’s house to get Sarah and Hatta and told Rebecca and the others what had happened.

The women hurried down to the wagon where they found Lott, Jake, and the children quietly waiting.

About half way home, the children asked if they could get off and take the shortcut through the woods. Away they ran, jumping and screaming like children who have been kept in the house too long.

The wagon slowly moved up the road with neither man saying a word. Finally, Sarah broke the silence.

“Boys, what did you two get into down there?” asked Sarah, nudging up to Lott the way she would when something was wrong.

Lott pulled the wagon to a sudden stop and turned to Jake. “I acted a fool down there, didn’t I? I was meddlin’ in someone else’s bus’ness, and I could have got you killed. I pray you’ll forgive me, and I ain’t going to meddle no more.”

“Lott, you hate slavery, and you got yore own feelings about it. I don’t care much for it neither, but for that Talbert, he’s got a lesson in manners comin’ some day, and I’ll be delivering the sermon to him. And for the apology, I owe you a thousand that I ain’t yet extended.”

As the wagon crept slowly toward the house, Lott told what had happened in town.

“Jake, I want you to stay out of Talbert’s way. That man sounds like he’s nothing but trouble. I don’t like for you to fight and hurt people, and I don’t want nothin’ to hurt you either,” Hatta said.

The women got off at the front steps and the brothers continued to the barn to unhitch the wagon.

“Jake, I heard that Bible verse that you was tellin’ Mister Walker ‘bout. You know, about drinkin You sure it’s in that verse in Matthew?” questioned Lott, impressed that Jake knew the scripture.

“Hell naw, I just made it up. I thought it sounded kind of good. Didn’t you?” laughed Jake.

“Jake, the Lord’s still got a lot of work to do on you ‘fore he can take you home. I just hope he gives ya the time it’s going to take,” replied Lott grabbing his brother playfully around the neck in an attempt to wrestle him to the ground.

“Well, it may take a while, but he sure got a helluvah job to do on that Talbert, and I might not give the Master enough time to reform that bastard, ‘specially if’n he messes with my Homer again.”

The next morning was Sunday, so the Wilsons were in no hurry to get up. The adults usually had a cup of coffee on the porch before the men and boys fed the livestock.

Lott, the last to arise, noticed Jake and Minsa down at the corral lazily looking over their prize horses.

Through the years, Minsa had adopted some of the white man’s ways. He still wore his hair long and often braided it back to keep it out of his face. But, with the shortage of deer and other wild animals, he now wore shirts and trousers made from a blend of cotton and wool. He especially liked red calico shirts. Most of the time he was barefooted; otherwise he preferred the leather moccasins worn by his people.

Minsa still lived with his wife and mother-in-law on the section of land he had chosen years before, but he had not tried to cultivate it. Instead, he worked for the Wilsons, taking care of their hogs and cattle which roamed the woodlands, and he took a special interest in Jake’s horses. Jake’s size still made it difficult for a horse to support his weight while racing, so Minsa who was much lighter and also an outstanding athlete became his substitute. Minsa had been taught the skills that could make him a champion. It was a wise move, because Minsa was excellent with horses and seldom lost a race.

Jake also encouraged Homer and let him race along with Minsa. Having two horsemen in a race doubled their chance of a victory.

Meanwhile, Lott had taken his coffee down to the corral to see what Jake and Minsa were discussing.

“Men, you up mighty early on this Sunday morning. You must be plannin’ some kind of campaign or sump’n,” stated Lott, making small talk and not expecting much in return.

“Well, big brother, we just lookin’ at these horses, and we think they’s just too short to keep up the winnin’. Sooner or later someone’s going to bring in some of them longlegged thoroughbred horses from up North and when they do, our winnin’ days is over.”

“They look good to me, and you boys has been bringin’ in the money on them races. What more do you want?” replied Lott.

“Look at them close. The best we got stands at fifteen hands tall, and Josh Clearman brought in one from up North a while back that stood over sixteen hands. He almost beat us,” Jake said, leaning over the top rail of the fence to study the horses more carefully. “He could’ve beat us if’n he knowed how to ride.”

“So, what are you tellin’ me, Jake?”

“We tellin’ you we got to get bigger horse if’n we is to keep on winning,” interrupted Minsa.

“Jake, me and Minsa has been thinkin’. If’n we had one of them thoroughbred horses to breed with the strong, quick horses we got now, we can keep on a winnin’ races. So what we got in mind is as soon as we get the cotton and corn out of the fields and get the fall hog killin’ done where we got the meat in the smokehouse, we goin’ North,” Jake said. “Me and Minsa got enough money saved to buy one of them animals and if’n we don’t, we’ll sell the horses me, Minsa, and Homer will ride up there on to take care of the rest,” explained Jake.

“Jake, how do you know where to go and who to see?” asked Lott knowing his brother was serious.

“We met a Mister Sam Jacobson from Tennessee a while back when we was over in Union at a dogfight. He had heard of our horses and we kind of got to talkin’ horse bus’ness. He said if’n we ever got up that way, he’d show us some of the finest horse flesh we has ever seen, and he even had some contacts up in Kentucky,” continued Jake.

“Well, you two is grown men and if’n that’s what you want to do, it’s fine with me. Just be sure to be home by spring plowin’ or we could have problems,” replied Lott. “And you sure better take care of Homer. He ain’t never been that far from home.”

“Forgot something,” interrupted Minsa. “I pick up letter several days ago at Walker’s store for you.”

He took a folded and crumpled letter from his pocket and handed it to Lott.

“Jake, this here’s Mamma’s writin’. Wonder how she’s a doin. Wonder if’n sump’ns wrong.”

He quickly opened the letter. The more he read, the more excited he became.

What’s in there, Lott? What’s goin’ on?” exclaimed Jake.

“Mamma’s comin’! Mamma’s comin’ to visit us next summer. She’ll be here the first of July. She’s comin’ to Coontail, Miss’sippi,” shouted Lott grabbing Jake by the hand. In a burst of excitement the two then began dancing a Scottish jig their mother taught them in Savannah.

The women up at the house thought the men must be hitting the jug again or had gotten into one of the large wasp nests under the barn roof. They were relieved and excited as the rest when they heard the reason for their unusual behavior.

Jake, Minsa, and Homer left the first day of November and headed north. They followed the Natchez trace as far as the middle of Tennessee where they met Mister Jacobson and from there rode into the eastern section of Kentucky. In what has been called “the blue grass country” they found exactly the horse they wanted, but it was priced higher than expected. It took all the money they had plus two of their own horses to acquire the animal of their dreams.

With only one saddle horse left and the magnificent thoroughbred they had no intention of riding, they set out south for Coontail. On the long trip back, two would ride and one would walk leading their prized possession.

Without money, the group had to hunt for food and sleep under the stars. Minsa, used to the outdoors, proved valuable to Jake and Homer in placing food before them each day.

Never had there been a happier group than the one that arrived on the 25th day of February 1851, at the front steps of the Wilsons’ home.

The family rushed out to greet the dirty, ragged group that had been gone for almost four months.

Standing before them was the tallest, finest looking animal the family had ever seen. He stood over sixteen hands tall, completely black except for a small white star between his eyes and another patch of white on the back of his right lower leg. Not only was he beautiful, but spirited and strong as well. He was something to behold.

Jake led the stallion up to Hatta. “I want you to meet the newest addition to the family. You name him, if’n you please.”

Hatta walked close and gently stroked his nose and patted his neck softly and whispered into his ear, “Your name, my hoofed brother, will be Lightning. You will strike and run quickly as a bolt of lighting streaks across the heavens with power of gods behind you. You and your offspring will bring glory and victory to our family. You will never be defeated.”