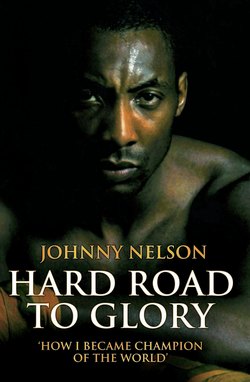

Читать книгу Hard Road to Glory - How I Became Champion of the World - Johnny Nelson - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 6

TWO MINUTES IS A LONG, LONG TIME

I didn’t start my amateur career until I was 17, by which time most young boxers have had dozens of fights and the good ones are already thinking of turning professional. It meant I seldom fought kids my own age. There were no junior fights for me against under-strength boys who couldn’t hurt anyone. As far as the boxing world was concerned I was a man and that meant several of my 13 amateur fights were against guys who weren’t good enough to be pros but were hard and enjoyed getting in the ring and hitting people. I was also tall, so my opponents tended to be close to heavyweight. They mostly had the advantage of experience and, unlike me, they wanted to be there. Many of them seemed to take special pleasure in beating up a black kid who was clearly anxious not to hit them back.

I used to travel to bouts with other lads from the gym, such as Paul ‘Silky’ Jones, who eventually became world champion, Leslie and Trevor Knowles, who would fight for fun, and the Kayani brothers, the original hot steppers when it came to boxing. They all had more potential than me, although only Silky went on to box professionally. On the way to fights they would boast how they were going to knock out their opponent, while I tended to sit quietly and watch the second hand on my tenth-birthday watch tick steadily through two minutes, the length of a round. Even sitting on the bus it felt like an age, far too long to be able to stay out of trouble.

I would offer a silent prayer that my opponent wouldn’t turn up. That was the best of all results and allowed me to describe in great detail on the way home how I would have smashed him if only he’d been fit enough to box. As I warmed to the subject, I’d figure that maybe he was fit – perhaps he just chickened out when he knew he was due to fight me. It was a different story when they did turn up.

My first fight was in Chesterfield. Time has thankfully wiped the guy’s name from the memory banks but nothing will ever let me forget the fear I felt when I saw him heave his way into the ring. He was massive, a monster. His scarred face and often-busted nose showed he was ready to hit and be hit. He didn’t look like someone who had ever known fear or felt pain. He came lumbering at me from the first bell and proceeded to blast the lights out of me. He didn’t allow me any time to catch my breath and was too strong for me to hold on to. He bullied me into a corner and wouldn’t let me out. There was no room for me to move – if he’d given me the space I would have gone down, but he was too wily for that. He was enjoying himself too much, toying with me. But he should have let me be counted out because, for a reason I will never understand, the referee gave me the verdict. It was one of only three amateur bouts I ‘won’ and I can only think they were awarding points out of pity that night.

The victory meant nothing to me – even I didn’t believe I had won – but the bout provided me with an early lesson that stood me in good stead through the rest of my career. I knew if I’d had the chance I would have gone down, but, as I thought about the fight afterwards, I was pleased he hadn’t given me the opportunity. I swore to myself I would never hit the deck voluntarily. It’s an easy thing to do but, if a fighter starts to jump on the floor when the going gets tough, it becomes a habit and eventually he will do it so often he might as well quit altogether. I hated taking punishment and Brendan and I worked hard to develop a style that meant I got hit as little as possible, but I didn’t want to be a coward. I decided then that, if my opponent landed a shot, I would take it and he would have to produce something special to put me down. I’m proud to say that I only went down three times in my 19-year professional career, and two of those were from foul blows.

Most of my amateur bouts were instantly forgettable but I do recall fighting Ian Bulloch in Bolsover, mainly for how it affected a title fight later in my career. Ian was a miner with a big following among his fellow pit men, especially in his home town. It was a very white, hostile crowd and, as I climbed into the ring, they started making jungle noises. I heard a few calling me a black so-and-so and one wag called out, ‘Watch him, Ian, he’s got a spear down his trunks.’

It was water off a duck’s back. Our gym had all racial types, as well as representatives of several religions and not a few heathens. There was always loads of banter, which Brendan encouraged, reasoning that, if we got used to it among our mates, it wouldn’t touch us when we got outside. I might not have been the best boxer in the world but even at that stage you couldn’t intimidate me with racial abuse.

Ian was powerful, too strong for me. He kept backing me up, hitting me with body shots and generally outmuscling me. I felt knackered. I noticed a clock on the wall and was trying to figure out how long there was to go when I heard the referee shout, ‘Stop boxing!’ He pointed to me and said, ‘You’re disqualified for ungentlemanly conduct.’

I was bemused – I didn’t know that looking at a clock was illegal – but I was also relieved because I’d been aware I was in danger of being knocked out. Nevertheless, I couldn’t help feeling I’d been cheated and Ian probably felt the same way, having been denied the chance to finish me off in the ring. Little did either of us know we would meet again a few years later, in much more significant circumstances.

Another bout sticks in my mind because of what happened outside the ring, and it was more humiliating than all my amateur defeats or disqualifications. It was an inter-club competition in Derby and I was up against a kid who was as reluctant to be hit as I was. We circled each other, tapping out jabs, most of them just out of range. We showed terrific footwork or, more accurately, terrified footwork. We bobbed and weaved, feinted to punch, switched stances, everything except land a meaningful shot. For two rounds, we never laid a glove on each other and finally the referee got fed up and threw us both out. I got changed and met up with Benjie who didn’t say a word as we headed for the car.

As we were going down the stairs, my opponent was walking up with a crowd of mates. They looked as though they were the real boxers in the club and their presence obviously made him feel braver.

‘If the ref hadn’t stopped it, I would have bust your arse,’ he said.

Who the hell did he think he was? ‘Oh yeah,’ I replied. ‘I don’t think so. I’d have bust your arse. I’d have slaughtered you.’

I then heard Benjie’s voice behind me: ‘Johnny, leave it. You weren’t gonna do nothing,’ and I had to walk out shamed, head down and with the sound of laughter following me all the way to the car park.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Clifton Mitchell, who was eventually to become a good friend, was in that little gang on the stairs. He told me later, ‘We were gonna kick off on the stairs and beat you up, but your dad did it for us, so we didn’t bother.’

I was clearly never going to be an ABA champion and I quickly tired of being given crappy prizes after bouts. The last straw was when I was given a small torch as a runner-up prize. Herol Graham and Brian Anderson kept telling me I was stupid to get hit for junk that ended up in the cupboard and that I might as well turn professional. I went to see Brendan and he told me I could only quit the amateur scene when I defeated a guy who had already beaten me twice. It wasn’t as big a hurdle as it sounds. I was bad but this fella was terrible. I knew I’d been robbed the first time we met and, even though he’d out-pointed me in the second fight, I still felt I could take him. He became my 13th and final amateur opponent. He truly was bad and I beat him up. In fact, I had more trouble from his wife who jumped into the ring after the fight, shouting at me and hitting me in the chest.

So, with just three less-than-convincing wins under my belt, I was a professional boxer. No one at St Thomas’s held their breath and I doubt if any of them bothered to tell their friends there was a new name in the Boxing Year Book. It’s a truism that there’s no place to hide in the boxing ring and it applies in the gym as well. On Sundays, St Thomas’s would be packed with people who had come down to watch the sparring and I vividly recall hearing Terry, the guy who used to drive the minibus to fights, saying to his mates as I started to spar, ‘Watch this kid, he’s crap. What a wanker. He couldn’t land a punch to save his life.’ He obviously thought I was deaf as well as useless.

But I couldn’t challenge him because he was right. When opponents went to hit me, I’d just put my hands up to stop the blows landing. It hardly occurred to me that I should be throwing punches back – that was what you did on the heavy bag or the speed ball. I was bricking myself each time I got in the ring and my body language screamed that this was no new Muhammad Ali. It wasn’t just Herol and Brian who wanted to spar with me. All the lads fancied their chances. Even the skinny kids realised I didn’t have a lot of bottle and that gave them confidence to have a go at me. There are a lot of people out there now who still find it hard to believe I became champion of the world and they tell disbelieving children, ‘I used to beat up Johnny Nelson,’ my first three professional opponents among them.