Читать книгу Death at Breakfast - John Rhode, John Rhode - Страница 5

Prologue

ОглавлениеVictor Harleston stirred uneasily. He grunted, then opened his eyes. Was he awake? Yes, he thought so. He stretched himself, to make quite sure of the fact.

It was still dark behind the closed curtains, on this January morning. Too dark for Harleston to see the time by his watch, which lay upon the table beside his bed. He was too lazy to stretch out his hand and switch on the light. Instead of this, he lay still and listened.

Very little noise came to him from without the house. Matfield Street was a backwater, lying not far south of the Fulham Road, and comparatively little traffic passed along it. One or two early risers were evidently about. Harleston could hear the hurried tap of a woman’s heels upon the pavement. This passed and gave place to a popular tune, whistled discordantly. A boy on a bicycle, probably. Considering that the window of his bedroom looked out at the back of the house, it was surprising how distinctly one could hear the noises from the street, Harleston thought idly.

But these were not what he was listening for. His ears were tuned to catch a familiar sound from within the house. Ah, there it was! A rattling of crockery. Janet would be along soon with his early tea. Harleston pulled up the eiderdown a few inches, and composed himself for a few minutes doze.

Then, suddenly, his memory returned, and in an instant he was wide awake. It was the morning of January the 21st, the day which was to make him rich! No more dozing for him now. Rather an indulgence in luxurious anticipation. Before the day was out, he could be his own master, if he chose. He hadn’t decided yet what he should do. Better not throw up his job at once. People might wonder. On the whole, it would be best to wait until the Spring, then take a long holiday and consider the future. There was no earthly need for a hurried decision.

He heard a door slam, somewhere downstairs, and then steps approaching his room. Janet, with the tea. It must be half-past seven.

Then the expected knock on the door, and a girl’s voice, ‘Are you awake, Victor?’

‘Yes, come in,’ he replied.

The door opened, and the girl placed her hand on the switch, flooding the room with light. She wore a gaily coloured apron, and was carrying a tray. Seen even this early in the morning, she was not unattractive. Full, graceful and unhurried in her movements. A slim figure, with her head well set upon her shoulders. Her face was certainly not pretty, but, on the other hand, it could not be described as ugly. Plain Jane, she had been called at school. And the nickname aptly described her. Janet Harleston was plain, without anything special about her face to capture the attention.

If you looked at her twice, you did so the second time because your curiosity was aroused. You wondered if her expression was natural to her, or whether something had occurred that moment to cause it. You noticed the sullen droop of her lips, the hard, unsympathetic look in her grey eyes. A sulky girl, you would have thought.

Her behaviour on this particular morning would have strengthened that impression. She put the tray down upon the table by Victor Harleston’s bed, and left the room without a word.

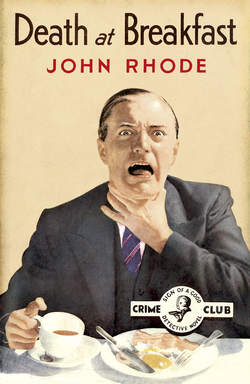

He made no effort to detain her. His mind was too full of plans for the future to find room for trifles. He raised himself to a sitting position, blinking in the sudden light. Seen thus, his face appearing above his brightly striped pyjamas, he was definitely unlovely.

Victor Harleston was a man of forty-two, and at this moment he looked ten years older. His coarse, heavy face was wrinkled with sleep, and his sparse, mouse-coloured hair, already beginning to turn grey, had gathered into thin wisps. These lay at fantastic angles on his head, disclosing unhealthy looking patches of skin. What could be seen of his body was flabby and shapeless. His eyes were intelligent, almost penetrating. But there was something malefic, non-human about them.

He yawned, disclosing a set of discoloured teeth, in which were many gaps, and looked about him. Janet was still upset, then. She hadn’t troubled to draw the curtains or light the gas-fire. Well, he couldn’t help her troubles. She’d get over them in time. She’d have to.

This last reflection brought a grin to his face. He loved to feel that people had to do what he wanted. At present, the number of such people was disappointingly small. Janet, and a few juniors at the office. It galled him to think that, up till now, he had himself had to do what his employer wanted. Up till now! Money was a precious thing, to be carefully hoarded. There was only one way in which a rational man was justified in spending it. The purchase of freedom for himself, and of servitude for others.

Still, he would have to make up his mind about Janet. He might make her an allowance, and tell her to go to the devil. But the prospect of parting with any of the fortune now within his grasp was repugnant to him. Why should he make Janet an allowance? Why part with one who was, after all, an efficient and inexpensive servant? He would only have to replace her, and the money spent on the allowance would be utterly thrown away, bringing him no benefit. Yes, that was the plan. He would stay here, in this house which was his own and suited him. But he wouldn’t spend the rest of his life earning money for other people. He would enjoy himself, and Janet should continue to look after him. But she must never be allowed to guess at his sudden access of fortune. That was a secret to be hugged to his own breast.

As for her temper, that had never troubled him yet, and it was not likely to now. She was too dependent upon him to let her ill-nature go to extremes. Dependent upon him for every mouthful she ate, every shred she wore. It was a delicious thought. He could dispose of her as he pleased. And it pleased him that she should remain and keep house for him. Victor Harleston poured himself out a cup of tea, added milk and sugar, and left it to cool.

He resumed his interrupted train of thought. No need to take seriously her threat of the previous evening. She would leave him, and go and stay with Philip until she found a job for herself! Not she! She knew too well which side her bread was buttered to do a silly thing like that. Jobs that would suit her couldn’t be had just for the picking up. There was only one job she was fitted for, that of a domestic servant. And what would Philip, with his high-flown ideas, say to that? It was all very well for the young puppy to encourage her. He wasn’t earning enough to keep her, that was quite certain. And he had a perfect right to forbid Philip the house, if he wanted to.

Victor Harleston drank his tea, and got out of bed. His first action was to draw the curtains. A sinful waste to use electric light if he could see to dress without it. Yes, it was a bright morning, clear and frosty. He switched off the light. Then he took a cigarette from a box which stood on his chest of drawers, and put the end of it in his mouth. He found the box of matches which he always kept hidden in a drawer, underneath his handkerchiefs. He struck a match, turned on the gas-fire, and lighted it. With the same match he lit his cigarette. No sense in using two matches when one would serve. Then he put the box back in its accustomed place.

As he did so, a sheet of paper which he had placed on the dressing table the previous evening caught his eye. It was a business letter. He read it over again, and smiled. All right. He had not the slightest objection to receiving something for nothing. He would try the experiment, right away.

Standing in front of the gas-fire, warming himself, his thoughts reverted to his impending fortune. He picked up a pencil from the mantelpiece, and with it made a few calculations on the back of the letter. The resulting figures seemed to please him, for he nodded contentedly. Quite a lot of money, if carefully husbanded.

He folded the letter in half, and tore it across. Then put the two halves together, folded them as before, and once more tore them across. With each of the four scraps of paper thus produced he made a spill. These he added to a bundle of similar spills which stood in a vase. No sense in wasting matches, when with one of these one could light a cigarette from the gas-fire.

He took his dressing-gown from a hook behind the door, put it on, and went along to the bathroom.