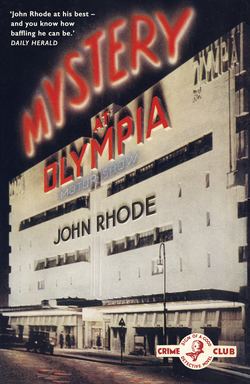

Читать книгу Mystery at Olympia - John Rhode, John Rhode - Страница 8

CHAPTER IV

ОглавлениеHanslet had not been long in his office next morning when he received a telephone call. He picked up the instrument. ‘Who is it? Mr Merefield? Yes, I know him. Put him through.’

The connection was established, and he heard the well-known voice of Harold Merefield, Dr Priestley’s secretary. ‘Hallo, is that you, Mr Hanslet? Good-morning. I say, do you know anything about an inquest on a chap named Nahum Pershore, who died at the Motor Show yesterday?’

‘As it happens, I know quite a lot about it,’ Hanslet replied. ‘Why?’

‘I’ll tell you. Oldland was here last night. It seems that he picked the fellow up, or something. He was telling Dr Priestley all about it. There doesn’t seem to me to be anything very special in his yarn, but you know what my old man is. He jumped at it at once. And he wants to know when and where the inquest is to be held, and whether you can get him a seat at it.’

‘You can tell him that I’ll keep a seat for him, all right. Two-thirty this afternoon, at the Kensington Coroner’s Court. Is that all?’

‘That’s all. Thanks very much. I’ll tell him. So long.’

Merefield rang off, and the superintendent leant back in his chair with a puzzled frown. What instinct had led Dr Priestley to evince any interest in the death of Mr Pershore? On the surface, there was nothing mysterious about it. An elderly man had collapsed in a crowd, that was all. Dr Priestley could know nothing about the curious incident of the olives. Yet that belligerent scientist, with his irritating passion for logical deduction, and his secret interest in criminology, seemed already to have detected an intriguing crime behind his friend Oldland’s necessarily bald account of the episode.

Well, so much the better. Hanslet had already thought of paying a visit to the house in Westbourne Terrace and putting the facts before the professor. He had a way of sorting out facts which was very helpful. They would meet at the inquest, and Hanslet would ascertain the professor’s impression later. Meanwhile he had plenty to do.

In the first place there was the analyst’s report, which had just come in. ‘Report on specimens submitted for analysis by Superintendent Hanslet, C.I.D. These consist of two bottles, marked “A” and “B” respectively, and bearing the label “Crescent and Whitewater’s Stuffed Olives.” Both bottles do in fact contain such olives, preserved in liquid. The bottle marked “A” contains twenty-four, the bottle marked “B” fifteen.

‘The analysis was for the purpose of ascertaining whether arsenic was present in the olives, and if so, in what quantity. The method adopted was to test first the liquid contained in the bottles, then each individual olive, then the pinkish mixture used as stuffing.

‘The first test was made upon the contents of bottle “A.” In this case, the results were entirely negative. No perceptible trace of arsenic was found in the liquor, nor in any of the olives or their stuffing.

‘The second test was made upon the contents of the bottle marked “B.” On testing the liquor, it was found to contain arsenious oxide in solution. The flesh of each olive was then tested separately, and yielded positive results, though the amount of arsenious oxide present was inconsiderable. On testing the stuffings, however, each of these was found to be contaminated with a small but varying quantity of arsenious oxide. In some cases, the crystalline particles of the salt were visible with a low-powered microscope. The amount of the salt present in each stuffing varied, but the average was half a grain. ‘This distribution of arsenious oxide suggests that the contamination had been deliberately carried out after the preparation and bottling of the olives. The method employed was probably as follows. The olives were removed from the bottle and treated separately. In each case the stuffing was removed, a quantity of arsenious oxide poured into the cavity, and the stuffing replaced. The presence of arsenious oxide in the flesh of the fruit could be accounted for by the absorption, and in the liquor by solution.

‘It may be of interest to Superintendent Hanslet to know that the smallest recorded fatal dose of arsenic is two grains.

‘The specimens are being retained in this department pending further instructions.’

So the olives had been poisoned, and Jessie’s symptoms were accounted for. If she had eaten four olives, she had taken two grains of arsenic, and might consider herself lucky to be alive. But what about Mr Pershore? If he had eaten five, by the same calculation he had taken two and a half grains. And he was dead. This seemed so logical to Hanslet, that he felt sure the inquest would be a very simple matter. The medical evidence would reveal that the cause of death had been arsenical poisoning.

He made a point of lunching early, and arrived at the Coroner’s Court in plenty of time. Dr Priestley was already waiting, and accepted the superintendent’s offer to find him a seat with a curt word of thanks. Shortly afterwards other witnesses began to arrive. Doctor Oldland, who greeted Hanslet with a nod of recognition and a slight lifting of the eyebrows. The police surgeon who had conducted the post-mortem. And finally Philip Bryant, at the sight of whom Hanslet frowned ominously.

The Coroner reached the court punctually on time, and the proceedings began without delay. He was sitting with a jury of seven, and when these had been sworn, the witnesses were called.

The first was Philip Bryant, who described himself as a solicitor, and gave his address as 500 Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He had seen the body of the deceased, and identified it as that of his uncle, Nahum Pershore. Mr Pershore was fifty-five, and lived at Firlands, Weybridge. He was a retired builder.

In reply to the coroner’s questions, Philip stated that he had last seen his uncle on the previous Sunday evening. He had seemed in very good spirits, but not quite in his usual robust health. Asked what reason he had for saying this, Philip replied that he had noticed at dinner that his uncle did not eat as much as usual. ‘I asked him tactfully after dinner if anything was the matter with him, and he told me that for the last couple of days he had been suffering from loss of appetite, with headaches and slight pains in the stomach.

‘I suggested to him that he had better see his doctor, but he told me that it was nothing. He attributed his symptoms to indigestion, from which he had already suffered some time previously. I knew that he was in the habit of taking some patent medicine for this, the name of which escapes me. I asked him if he derived any benefit from it, and he told me that he did, and that he would take an extra dose that evening.’

‘Did he appear in any way mentally depressed at his condition?’

‘Not at all. He was as cheerful as I have ever known him, and spoke of going for a Mediterranean cruise in a few weeks’ time.’

Philip stood down and the police surgeon was called. He gave his name as Cecil Button. He had been instructed to perform a post-mortem examination of the body of the deceased, and had done so that morning.

External examination had revealed no bruises or contusion of any kind. But, upon removing the clothing, a strip of linen, which appeared to have been torn from a shirt, was found tied round the right thigh. Upon removing the strip, it was found to be spotted with dried blood, not in any considerable quantity. Examination of the place from which the strip had been removed revealed three punctures, and on probing them, a corresponding number of pellets were found embedded in the flesh. These pellets had been removed. Doctor Button passed a small cardboard box up to the coroner for his inspection.

The Coroner opened the box and looked at its contents. ‘These appear to be shot from a twelve-bore cartridge,’ he remarked. ‘Is it your opinion, Doctor Button, that these injuries contributed to the death of the deceased?’

‘I hardly think that is possible,’ the doctor replied. ‘By the appearance of the very slight wounds, I formed the opinion that they had been sustained at least forty-eight hours before I examined the body, and possibly longer. They showed no signs whatever of being septic, and their position was such as to cause no danger, but only slight inconvenience. I noticed also that the skin in their vicinity was stained with iodine.’

‘Did you form any opinion as to how these wounds had been inflicted?’

‘They appeared to me to have been caused by a shot-gun, fired at considerable range. The pellets were widely scattered, the punctures being rather more than two inches apart. And the penetration of the pellets into the tissues was not more than an inch.’

‘You found no other sign of external injury?’