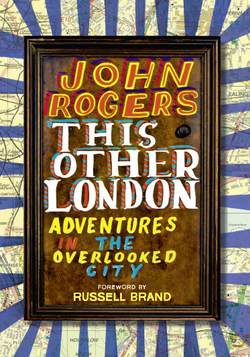

Читать книгу This Other London: Adventures in the Overlooked City - John Rogers - Страница 6

Оглавление

‘Exploration begins at home’

Pathfinder, Afoot Round London, 1911

Backpacking in Thailand in my early twenties I climbed down off an elephant in a small village in the mountains of the Golden Triangle. The streets of 1994 East London felt far away – I had broken free for new horizons. I entered a small wooden hut where a villager prepared freshly mashed opium poppy seeds in a long pipe. In Hackney such men were called drug dealers – here they were known as shamans. ‘Across the rooftop of the world on an elephant’, I wrote in my travel journal. The flight to Bangkok had been the first time I’d been on a plane; my previous travels hadn’t extended beyond a coach trip to Barcelona. The top of this mountain was the edge of my known world – the real beginning of an adventure.

In the gloom of the hut was another group of travellers – fellow explorers and adventurers. I spoke to the pale, willowy girl sitting next to me, dressed in baggy tie-dye trousers, a large knot of ‘holy string’ on her wrist from a long pilgrimage around India. She told me stories about an ashram in the Himalayas and gave me the address of a man with an AK47 who could smuggle me across the border into Burma. A few more minutes’ conversation revealed that this wise-woman of the road was an accountant on sabbatical who lived two doors down from my sister in Maidenhead. I had come 6,000 miles to a remote mountainous region to sit in a shack with a group of Home Counties drop-outs chatting about a new Wetherspoon’s in the High Street.

Hostel dorms were full of wanderers who claimed to have ‘discovered’ beaches and villages merely because they weren’t in the latest Lonely Planet Guide, ignoring the fact people were already living there. Seemingly there was nowhere left to ‘discover’, the whole world was very much ON the beaten track. I spent two years bunkered down on Bondi Beach but longed for windswept, collars-up London evenings, to be in this city indifferent to the whims of the individual, a slowly oscillating hum of existence, to feel millennia of history squelching beneath wet pavements. I also missed a decent pint of beer that wasn’t served in a glass chilled to the point that it stuck to your lips.

Returning to London and eventually starting a family didn’t mean settling down. I usually wear walking boots and carry a waterproof jacket just in case I spontaneously head off on a long schlep towards the horizon. I’ve remained on the move.

One Sunday winter evening I travelled five stops on the Central Line from Leytonstone to Liverpool Street to walk along the course of the buried River Walbrook. I didn’t see a soul until I popped into Costcutter on Cannon Street to buy a miniature bottle of Jack Daniels to drink on the pebble beach of the Thames beside the railway bridge. The backpacker trail had been as congested as the rush-hour M25, whereas the pavements above a submerged watercourse running through the centre of one of the biggest cities in the world were deserted. If I’d taken an afternoon stroll in the Costwolds I’d have been tripping over ramblers at every field stile, but here I had the streets to myself, the only other people I saw were the snoozing security guards gazing into banks of CCTV monitors. This walk, inspired by an old photo I’d seen in a book bought in a junk shop of a set of wooden steps leading down from Dowgate Hill, had led me to a land twenty minutes away from my front room more mysterious than anything I’d encountered in Rajasthan or the Cameron Highlands.

Randomly flicking through the pages of an old Atlas of Greater London a new world revealed itself. The turn of a wad of custard yellow pages and there was Dartford Salt Marsh reached by following the Erith Rands past Anchor Bay to Crayford Ness. Skirt the edge of the Salt Marshes inland along the banks of the River Darent, down a footpath you find yourself at the Saxon Howbury Moat.

This atlas of the overlooked was richly marked with names written in italics that would be more at home on Tolkien’s maps of Middle Earth in The Lord of the Rings than in the Master Atlas of Greater London. Hundred Acre Bridge should be leading you to a Hobbit hole in The Shire rather than to Mitcham Common and Croydon Cemetery. Elthorne Heights and Pitshanger sound like lands of Trolls and Orcs but where the greatest jeopardy would be presented by my complete inability to read a map or pack any sustenance beyond a tube of Murray Mints.

I set out to explore this ‘other’ London and pinned a One-Inch Ordnance Survey map of the city to the wall of my box room. It felt unnecessary to enforce a conceit onto my venture such as limiting myself to only following rivers, tube lines or major roads. I also didn’t fancy the more esoteric approach of superimposing a chest X-ray over the map and walking around my rib-cage. I wanted to just plunge into the unknown – ten walks, or what now appeared as expeditions, each starting at a location reached as directly as possible with the fewest changes on public transport, then hoof it from there for around ten miles, although it’d be less about mileage and more about the experience. I’d aim to cover as much of the terra incognita on the map as possible, spanning the points of the compass and crossing the boundaries of London boroughs as I had done borders between countries.

It was essential to embark on this journey on foot. For me walking is freedom, it’s a short-cut to adventure. There’s no barrier between you and the world around you – no advertising for winter sun and cold remedies, no delayed tubes or buses terminating early ‘to regulate the service’. Jungle trekking in Thailand and climbing active volcanoes in Sumatra were extensions of walking in the Chilterns with my dad as a kid, and wandering around Forest Gate and Hornsey as a student. Through walking you can experience a sense of dislocation where assumptions about your surroundings are forgotten and you start to become aware of the small details of the environment around you. At a certain point, as the knee joints start to groan, you can even enter a state of disembodied reverie, particularly with the aid of a can of Stella slurped down on the move.

When you walk you start to not only see the world around you in a new way but become immersed in it. No longer outside the spectacle of daily life gazing through a murky bus window or ducking the swinging satchel of a commuter on the tube, on foot you are IN London.

The explorations I’d carried out over previous years had taught me to expect the unknown, to never deny myself an unscheduled detour, and that even the most familiar streets held back precious secrets that were just a left-turn away. Most of all I knew that the more I gave in to the process of discovery the more I’d learn.

I’d initially been inspired to head off travelling round the world by reading the American Beat writers who gallivanted coast-to-coast across America looking for a mysterious thing called ‘It’. After finally landing in Leytonstone I wondered if enlightenment was just as likely to be found on the far side of Wanstead Flats as at the end of Route 66.