Читать книгу My Bonnie: How dementia stole the love of my life - John Suchet - Страница 6

Chapter 1

Оглавление27th April 1983

Bonnie and I are going to be together at last. I was up at dawn, tidying the bedsit of which I am so irrationally proud. We both had large houses in the English countryside, but I think I love this bedsit more than anywhere I have ever lived. Before breakfast I polished the kitchen and bathroom floors on my knees, then vacuumed the rugs in the main room. After breakfast I went out to the florist and bought some flowers. I didn’t know what to get. The girl said, May I ask what they are for? I grinned from ear to ear. To welcome someone very special, er, a woman. She smiled knowingly and selected something. I can’t remember what she chose. As I left the shop, clutching the bouquet awkwardly, I realised I had nothing to put it in. I went back in. She laughed. I bought a small green vase, pinched at the middle, with slanted ripples in the glass. It is on the sideboard and I am looking at it now as I write this, 26 years later.

I drive to Baltimore Washington International airport in the office Volvo, cursing the traffic that has made me a little late. I park and run towards the arrivals terminal, praying she has not come through. I don’t see her at first, then I realise it is her. A slim figure standing outside the doors. She is wearing a long summer skirt and coloured short-sleeved top. She has her hand on the extended handle of a suitcase. On top of the suitcase is an open wicker bag. Then I realise why I hadn’t at first recognised her. On her head she is wearing a straw hat. Round it are large multi-coloured paper flowers. The hat has cast her face into shadow.

I stop and look at her. She seems so frail. She has lost weight. Those wonderful high cheekbones give her face a fragile beauty. My breath quickens and my heart beats more strongly. My Bonnie is here. She has come to live with me. Her smile when she sees me is nervous, but it lights up her face.

In the car we are silent. I turn to her a couple of times. Each time she returns my smile, but I can sense the anxiety. Why are you anxious? I ask, cursing myself for the stupid question. I’m just a bit nervous, she says. I try to comfort her with a smile.

We walk along the corridor, and I open the door to my bedsit. The first real test. What will she say? Will she like it? Will she recoil in horror at the smallness of it? But I’m not really worried. She throws her arms out, does a twirl, and says it’s lovely.

I fold her up in my arms, breathe her in, stroke her skin. I look into her eyes as her eyelids slowly close and she turns her face up to mine.

In the evening, as she prepares a simple dinner, I open a bottle of sparkling wine and we toast the future. I spread a green cloth over a small table, both given to me by my camera crew. She takes two candleholders and two slim white candles out of the wicker bag, places them on the table and lights them.

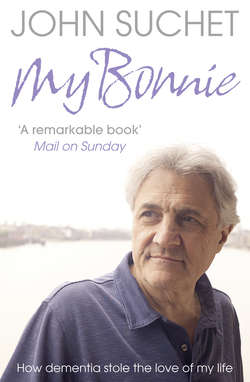

With slight trepidation (not all women like being photographed at a moment’s notice), I ask her if she would mind if I took a photograph. I never want to forget this moment, I say. Of course not, she says, giving the ends of her hair a little flick. I set up my old mechanical Nikon on some boxes and books, activate the self-timer, and run back to the table. One day, I say to her, I will write our story, and this photo will be on the cover. And now it is.

Her name is Bonnie, and no, it is not short for anything. Her father named her after Rhett and Scarlett’s young daughter in Gone With The Wind. (She came to a sticky end, but we’ll let that go.) He named his only daughter Bonnie because he liked the name, simple as that. Bonnie herself has not always been so fond of it. When she worked in London for an international charitable foundation, she complained to me that most people called her Bunny. Pointing out her name was actually Bonnie didn’t improve things much; the damage was done, and she believed they didn’t take her seriously. I have always adored the name. It is understated, friendly and instantly likeable.

She was born in New Jersey in 1941, and if you want a comparison for her in her younger years, think Grace Kelly in High Society, the archetypal elegant and cool American East Coast blonde. For a later comparison, the actress Lee Remick will do. In the years when I pined hopelessly for her and she relished my company only in my fertile imagination, I contented myself by putting her alongside Grace and Lee, my trio of American blondes, all utterly lovely and utterly unattainable. Don’t be too hard on me; a man is allowed his fantasy.

So the fact that she is beautiful is incontrovertible. It is simply a fact. A cursory glance at some of the photographs in this book will be enough to convince any doubter, but if you demand further proof, then brace yourself for this: by the time she was 20 years of age Bonnie was four times beauty queen. Not once, twice, or even three times, but four times. At each school she attended she was voted beauty queen and, most prestigious of all, at Cornell University she was crowned Homecoming Queen.

In case you should form the wrong opinion, I would like to stress that in not a single case did she put herself forward for these contests. In the early years it was a combination of school and parents, and at Cornell it was the students themselves who chose her. Not much upsets my Bonnie, but in years gone by if ever I wanted to make her just that tiny little bit fractious, I would remind her she was four times beauty queen. ‘No, stop that,’ she would say, ‘you’re embarrassing me.’ I would gently josh her, force that radiant smile to emerge, then hug her till it hurt.

In her final year at Cornell, she and a small group of female friends came to Europe to explore the Old World. The young men of Italy, Spain, France, thought all their Christmases had come at once—I know so because she told me that one day one of the other women said to her, ‘If you get another one tonight, could you pass him on to me’. But Bonnie left them to nurse damaged hearts—except in England, where one persistent suitor was ultimately to be rewarded. She went back to Cornell, but after graduation Bonnie returned to London and married her Englishman.

She later told me that from the day she set foot in England she felt as if she was returning home. Everything about the old country appealed to her, and she knew immediately she would make it her home. As I write this, she has lived in the UK for more than 40 years.

You don’t need to know much about me, so I will keep it brief. I was born in central London in 1944, the eldest son of a much-respected gynaecologist and obstetrician. Today I live with Bonnie in the same block of flats in which I spent the first 10 years of my life (two doors away on the same floor).

My school career was remarkable for its ordinariness. I made a lot of noise and achieved very little. At prep school I was caned relentlessly, along with my brother David, by a sadistic headmaster. At public school I was punished by a narrow-minded music director for playing jazz on school premises. I was relatively good at modern languages—French, German, Russian—and taught myself to play trombone to quite a high standard (which led to the offending jazz session). I managed to fail or achieve only mediocre passes in all exams, even in my stronger subjects, but a fortunate phone call at the right moment to the right faculty earned me a place at university. It was in Dundee, which shocked my parents, and we had to look at Dad’s AA road map of the UK to find out where it was. Four years later I was a Master of Arts (with Honours) but, more importantly, I had secured a position as graduate trainee with Reuters news agency in Fleet Street, London.

I will not bore on about exactly how I achieved that, other than to say that it was a combination of a certain ease in writing a news story, combined with a shameless exaggeration of my linguistic skills, which at interview were never put to the test. Just recently, around 40 years on, I was host at a social event in the City of London, at which the two former Reuters executives (long since retired) who had interviewed me were present. In my speech I finally confessed to them that had they tested my claims as a linguist, I would have been on the next train north. There was much laughter, and a few good-natured boos.

The start to my Reuters career was stellar. Eight months after joining—a year since my graduation—I was on the streets of Paris, covering the student riots of 1968, which ultimately led to the downfall of President de Gaulle. But, true to form, I then proceeded to make a mess of things by turning down the opportunity to become bureau chief in Congo Brazzaville. (It was a startling promotion, but my then wife insisted we needed to stay in the UK to look for a house and take out a mortgage. So I turned down Brazzaville, knowing I was making the first major mistake of my fledgling journalistic career.) I resigned, failed to find another job, then a fortunate phone call to the right person at the right time landed me a lowly job in BBC television news, writing the football results and weather forecasts. I managed to do even that quite badly, and after a year-and-a-half left for ITN, telling the BBC I would be back in a year. I stayed at ITN for the rest of my career. In 2008 the Royal Television Society presented me with a Lifetime Achievement Award, its highest accolade. I don’t know why—I’m convinced they got the wrong person—and when I look at the very smart gold and engraved glass award sitting on my grandparents’ glass-fronted cabinet, I regularly say to Bonnie that when they realise their mistake it’ll be too late, they’re not getting it back.

Back at the beginning of 1970, with my career in tatters, my first wife Moya and I moved into a Victorian cottage at the end of a cul-de-sac in leafy Henley-on-Thames and I took on a crippling mortgage. The house was cold and damp and parts of it were at risk of falling down. It needed a lot of work, and I had never held a drill in my life. A small slope went up into woods opposite our house. Three new houses had been built on it, red brick, boxlike, unattractive. In the summer of 1970, Bonnie and her husband moved into the house at the top of the slope.

I am writing this at the large oak dining table in the old farmhouse Bonnie and I bought 20 years ago in Gascony in south-west France. Bonnie is walking slowly around the house. It’s what she does now. She can’t settle. She stands at the kitchen door, squinting at the brightness outside. She walks the length of the kitchen, then into the sitting room, which we call the séjour, where I am writing. Hello darling, I say, I am writing about you. Good, she says, without questioning me any further. On the table is a large brown envelope with my name on it. Inside are sample chapters of a forthcoming book in which carers tell their stories of caring for a loved one with dementia. The author has asked me to write a short paragraph endorsing the book. Bonnie picks up the envelope, but I am not worried she will open it or even ask what is in it. Have you seen this, she asks?

Yes, I say, affecting a slight weariness in my voice. It’s from a charity I am doing some work for. They want me to read it and give my comments. Lot of stuff to get through. She smiles and puts it down, and walks back to the kitchen, where she stands at the door and squints her eyes again at the brightness outside.

I haven’t lied to her, I have told her something which is very close to the truth and which I know she will be comfortable with. I am getting better at entering her world and only saying things I know she will comprehend. I mustn’t try to take her outside her world. The tragedy is that that world is slowly shrinking, so something she may grasp today may elude her tomorrow. I have to be on the lookout for that.

I said she doesn’t settle. It is strange, and at first—for some time, in fact—I found it irritating and rather wearying. Why don’t you sit down, love? Sit in an armchair and relax. All right, she would say, and continue her gentle pacing. Do not try to take her outside her world. So now I say nothing. She is content. But I do have the power to alter things. If I close the computer now, get up, say I have finished writing, and go and sit in an armchair, she will come and sit in an armchair with me.

She has been patiently pacing for the last couple of hours while I have been filling you in on my unillustrious past, so the time has come to stop and give some time to her. So if you’ll excuse me…

My first wife Moya and I had a volatile, combustive relationship. Although from totally different backgrounds, our temperaments were rather similar. We were both highly strung, emotional, quick to judgment, with a temper. She came from a Scottish family and was proud of her Celtic blood. I came from, er, lots of different places. Yet we were both, to simplify, ‘artists’ rather than ‘scientists’. We liked books, theatre, films, music. Only problem was we liked totally different books, theatre, films, music to each other. There would be fierce argument about the merits or de-merits of a particular work of art, with measures of intolerance and ridicule thrown in. There was rarely a meeting of minds.

I was 19 when we met and 24 when we married. Ridiculously young, really, but I was the product of a ‘boys only’ education. At prep school the most popular boys were the ones who had a sister who just might come to visit, which would mean a rare sighting of a sublime creature with long hair wearing a skirt and maybe—god, the thrill of expectation —a touch of lipstick. At public school we were expressly forbidden from talking to girls who lived in the town. A boy who had the temerity not only to do that but to date her as well, was expelled between making the date and keeping it. How then to get to know these wonderful creatures? How to approach them, what on earth to say to them? For me even at 18, girls were mysterious and desirable creatures from another planet. I had no idea how to talk to one, let alone how to embark on anything more daring. And so practically the first girl who (finally) allowed me to kiss her became my wife.

My parents could see that, in marrying Moya, I was about to make the mistake of my life. Both tried hard to talk sense into me, to make me change my mind. Does a very young man who has secured an Honours degree in Political Science and Philosophy, who has landed the job of a lifetime at the first attempt, listen to his parents? Some may, but this one did not.

Problem was, Moya knew full well the lengths my parents had gone to in their attempts to stop me marrying her, and so once we were married she insisted I was to have nothing more to do with them. Nothing. I wasn’t to see them, or try to make contact with them in any way. I had a new life now, with her. Even I could see that was a bit extreme, but I let it go. Emotions were running high. I thought in time they would settle on both sides, and life would get back to normal. But it didn’t. She really meant it. I soon learned that even to mention my parents was to invite trouble. Still I did nothing to correct the situation. The birth of our first son, Damian, did little to calm things down. I threw myself into my work, and when we moved out to Henley it put physical distance between me and my ‘old’ family. Always at the back of my mind was the belief that one day matters would correct themselves, but in the meantime it simply became easier to carry on doing nothing. It made for an easier life.

Two more sons, Kieran and Rory, arrived, but I wasn’t allowed to tell their grandparents, never mind take them for a visit. How much longer would this new way of life last? I clung to the belief that it might end at any moment. My worst nightmare was that one of my parents would die before it was rectified. I felt guilty that I was allowing it to happen, but couldn’t think how to resolve it without damaging my increasingly strained marriage.

Meanwhile, my attention had been caught by the young blonde woman who lived in the house at the top of the slope. I had found out her name was Bonnie. She was stunningly beautiful and around her shone an aura of calm. Even before I had exchanged anything more than social pleasantries with her, I knew profoundly, totally, with not a shred of doubt or hesitation, that this would be my ideal woman. Sadly, a woman who could never belong to me. Too bad. I wouldn’t be the first man to find himself in such a position. At the very least, I thought, I would enjoy getting to know her, and derive pleasure from that.

Dreams are cruel and memories hurt. Just before waking this morning, I had the most intense dream about Bonnie. The old days were back. You can imagine. I awoke to feel her getting out of bed and knew I would have to lead her to the bathroom. Black dog depression on my shoulders. I got her dressed, and saw hanging up one of her favourite tops, colourful, beautiful, elegant. Boy, she used to turn heads when she wore that. It has been untouched for years. There is no point in reminding her of it—she would just smile and say yes. I touched it, as I used to, and stroked the buttons I was once so expert at loosening.

At breakfast she stood and walked to the kitchen door. She chuckled and said in a mock Cockney accent, ‘Is that your car?’ ‘Sorry?’ I asked. She repeated it, adding, ‘You know, that’s what those people say, those people, you know the ones, they just came in.’ I laughed and agreed. In fact, it is an annoying ad running on UK television at the moment, and she has memorised the catchphrase.

Good start to the day, triple whammy depression. I snap myself out of it, repeating the mantra—no self-pity, John, no self-pity. But it is so difficult. Here she is again now, just walking in and out of the séjour, while I tap-tap away, conjuring her up in my mind as she was in those long-gone, distant days, when I responded to her every word, every casually administered gesture. In my mind there is one person, in front of my eyes another, different person. It is impossible to stop the tears.

Bonnie and I met socially over the years, as neighbours do. When we were together my senses were heightened, my brain was more alert, my wit quicker, my conversation more sparkling (at least I thought so). She would respond with a serene and gentle smile, and softly spoken words. I thrilled at her accent, the anglicised American tones, the long ‘a’s and audible ‘r’s. Nothing dramatic or obvious. With Bonnie, everything was soft, gentle, subtle. Later, I would relive every word she had said to me. Was there a message, a sign? Was she trying to tell me something secret and important? Of course not, you fool.

At a dinner party at her house some time in the early to mid seventies, I saw a framed photograph of her with three smiling young men. I asked who they were. ‘My brothers,’ she replied. At the back of the group, the tallest had a strikingly handsome face, prematurely greying hair and neat beard. ‘You look so like him,’ I said. Her face lit up. ‘That’s Bob, the eldest. I’m next.’ ‘Nice looking,’ I said, ‘you all are.’ (Bold, I remember thinking, maybe too bold.) To my delight she began to talk about her family. She told me that her father was an executive with US Steel, which had meant moving the family across the US. She told me she had been born in Jersey City, but had lived in Maryland, Alabama, California. ‘In fact, it’s quite sad about Bob,’ she continued. ‘He really loved it in California. We lived in Whittier, just outside Los Angeles—’ ‘Nixon,’ I interjected, ‘he came from there.’ (Shut up, you fool, let her speak.) She nodded. ‘He was doing so well in school, he was academically bright, he was captain of the football team, he had a lovely girlfriend. But then US Steel wanted Dad to come back east. It was a huge wrench for Bob. He kind of gave up, he stopped trying. But he’s fine now. He’s got a lovely wife. In fact, one day you must meet my brothers. They’re bound to come over sooner or later.’

I can’t remember much more of what she said. I just wanted her to go on speaking and never stop.

In December 2008 there was a family wedding in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Bonnie’s nephew—son of her youngest brother—was getting married. I was worried about making the journey because of Bon’s health. Also it would mean staying in a hotel, with all the confusion that would bring. But it was vitally important we attend. Bon’s eldest brother Bob was terminally ill with oesophageal cancer. He had undergone several bouts of chemotherapy, but his lungs were filling up, requiring regular draining. The doctors had sent him home and warned the family he didn’t have long to live.

We went, and Bonnie coped better than I expected. There were a couple of middle-of-the-night excursions into the hotel corridor, but nothing I couldn’t handle. What really surprised me, though, was how Bon reacted to Bob’s illness. He was, frankly, in an appalling state. Skin and bone, protruding spine, sunken face, staringly bright eyes. I hugged him, and he let out a shout—I had pushed the permanently inserted catheter against his ribs. But Bon didn’t seem overly distressed. In one extraordinarily poignant moment, I saw her holding his hand and heard her telling him he must get better.

Thank goodness we made the journey. Bob died two months later. I haven’t told Bon. Why make her sad? She doesn’t need to know.

Things definitely changed some time around 1978. There was a big dinner party, about a dozen of us, all local couples, and we held it in a fancy restaurant, the French Horn in Sonning. I found myself sitting next to Bonnie, with both our spouses a fair distance away on the other side of the table. She had swept her blonde hair back from her face and held it in place with two cream combs. I don’t think I had ever seen anything more lovely. It set off her face in all its beauty, her peach skin and sparkling eyes vibrant and alive. I was in heaven. We chatted together right through the meal. God knows who was on my left or her right, but they might as well not have existed. It was the longest I had ever spoken to her for, and I wasn’t going to waste a second of it.

I could say my wit was at its sparkling best, and you would groan and roll your eyes, but really it was. Late on in the meal, she was asking me about my job. I told her I was an ITN reporter and mentioned one or two stories I had covered, and she said she had seen me on News at Ten. I was flattered. I wanted to ask her what she thought, but decided not to put her on the spot.

Then she said, and I remember it perfectly more than 30 years later, ‘Aren’t journalists supposed to be rottweilers?’ I laughed and replied, ‘Well, not me, I’m just a poodle.’ She burst into uncontrollable laughter. She threw her head back, her hair cascaded round her face, dancing below the combs. Then her head came forward, shimmering tears of laughter in her eyes. She put her hand on my arm to steady herself, but still her laughter shook her body, a sound more beautiful and joyous than any I had heard. I glanced quickly around the table—all heads had turned. Still she laughed, looking me in the eye now. Very slowly her laughter began to subside, but her cheeks were flushed, her eyes still fiery bright. She took a swallow of water. ‘You are funny,’ she said, and looked at me in a way I cannot describe. There was something new about it, something intimate.

I will wind the clock forward 10 or 12 years. We were by now married, and having dinner with a business colleague of Bonnie’s and his wife. Bonnie looked stunning in a dark skirt and colourful shaped blouse that showed her off to perfection. Her lovely hair was again pulled back and held in place by those two cream combs. ‘How did you two meet?’ the man’s wife asked. Bon shot me a look. She always felt slightly uncomfortable if I said we had been neighbours, and had asked me in the past to say something to the effect that we were introduced by friends, something neutral which should not lead to more questioning.

I said, ‘We were in a crowded room, our eyes met, I said Ugh, she said Ugh, and that was that—we are not very good with words.’ Bon did that laugh again. It was an exact repeat of the French Horn. She threw her head back and laughed until her ribs hurt. I laughed with her. The man and his wife looked at each other and joined in the laughter, but not very fully. I caught a look she gave him, which sort of said, ‘Why can’t you make me laugh like that?’

On the way home, Bon said she loved what I had said, she would never forget that it all began when we said Ugh to each other, and we laughed together all over again. Those combs are in a drawer of her dressing-table in our flat to this day. Just a few months ago, I saw her walking around the flat with them in her hand. She didn’t put them in her hair, just carried them around, occasionally putting them in her cardigan pocket, then taking them out again. I didn’t say anything. If I had said, Do you remember how I used to love you wearing those, she would just have said yes. But she wouldn’t remember really, and it might cause her a little pain deep down because she would know she doesn’t really remember. Later she put them back in the drawer and hasn’t taken them out since.

‘I am writing about you, my Bonnie.’

‘Oh are you? That’s nice,’ and she walks away.

There was a subtle change one summer’s evening in, I think, 1979. Bonnie and her husband invited my wife and me up to their house for dinner. Don’t think me vain, but I can remember exactly what I was wearing that night, and for good reason. I had on a dark blue blazer, open neck blue shirt and new pale blue slacks. We arrived a little early (probably my fault), the back door was open, and Bonnie called down to us to make ourselves at home in the sitting room, that she and her husband would be down in a minute.

There was a news journal on the coffee table. I picked it up and flicked through it. Aware that she would walk through the door at any moment, I affected insouciance, standing in relaxed manner, weight on one leg, the other informally outstretched, not taking in a single word on the printed page in front of me, hoping I was striking an irresistibly alluring image. The minutes passed. Finally I heard the light footsteps approaching, I adjusted my pose slightly—back that little bit straighter, biceps slightly flexed, one eyebrow subtly raised, nostrils marginally flared, a look of utterly false concentration on my face as I affected to be studying a learned article about something happening somewhere in the world. She walked in. I raised my head slowly and at an angle, a Cary Grant smile playing on one corner of my mouth, hoping it would strike the perfect combination of intelligence and pleasurably interrupted concentration.

‘Ooh look,’ she cooed, ‘John all dishy in blue.’

I chuckled in a manly way and flicked my head so a lock of hair fell springily onto my forehead. Rather that’s what I wished I had done. In fact I half-dropped the journal, slightly lost my balance on the supporting leg, caught my breath so I nearly choked, and all round made a pretty damn fool of myself.

But she said it, she really did say it. I remember the words exactly, and can even hear her tone of voice—mild, pleasurable and seductive—30 years on. After that, I spent the evening in a sort of daze. I can’t remember anything of how the dinner went, what we talked about, except that I recall running those few words through my head again and again and again. Why did she say it? What did it mean? Was she trying to say something more? Was it, in fact, a subtle way of saying something else?

I knew I was fooling myself. The answers to all these stupid questions were pretty obvious. She said it on the spur of the moment, without pausing for thought. But that in itself was amazing enough: it meant she really thought it. If she hadn’t thought it, she wouldn’t have said it. I reasoned that much, so I probably spent the rest of the evening with a foolish and rather smug grin on my face.

There was more to come. When it came time to say goodnight, Bonnie and her husband escorted us out of the front door. It was a warm rather sultry evening. It was customary to administer a French-style peck on both cheeks. She and I had done it a dozen times at various social functions. I moved towards Bonnie, she moved towards me, and as I leaned forward she didn’t turn her head, so I kissed her on the lips. Just fleetingly, no more than a split second. But all the clichés happened. A shaft of heat shot through my body, a mini-explosion went off in my head, my mouth hung half open, a smile spread from ear to ear. I let her go, I couldn’t repeat it, but as she drew back her eyes didn’t leave mine.

Now I really did have a question to ask myself. Was that deliberate? I lay in bed that night asking the question, I awoke the next morning still asking the question, and continued to ask it for the next several months, during which I did not see her. It had to be, didn’t it? Would a woman accidentally do that? Surely not.

You will not be surprised to learn that some years later, when we were at last together, I asked her the question. I didn’t expect her even to remember the occasion, let alone what happened, so I began at the beginning, as it were, by reminding her we had arrived a little early and I was standing reading the news journal. ‘And I said John all dishy in blue,’ she interrupted. ‘Yes, and when we left at the end of the evening…’, ‘I kissed you on the lips,’ she said.

My parents were totally out of the picture. Not totally out of my mind, but Moya didn’t know that. I had successfully sublimated the guilt, so that as far as she was concerned my life revolved exclusively round my ‘new’ family.

There were jolts. I was crossing a footbridge at South Kensington tube station one day, and there was a huge poster that said, ‘Honour thy Father and Mother’. I swallowed hard and cursed the interfering group of religious bigots that had put it up. I would dream of Mum and Dad, and wake with a leaden feeling of guilt in my head. Then, at a social gathering one Christmas at the home of a mutual friend who lived in the same road, Bonnie and I were engaged in polite conversation. I think we were talking about Watergate, President Ford’s outrageous pardon of his predecessor, something like that anyway, when—clearly intending no more than a continuation of chat—unwittingly Bonnie rocked me to the foundations. She asked me about my family, my parents. Nothing abnormal about that, except to someone in my situation. I tried to think quickly of something appropriate to say, something that would sound fine and lead to no further questioning. But what came out was ‘I, er, I don’t see my parents.’ I prayed she would simply move the conversation on, but she was appalled. She repeated what I had said, pausing between each word.

‘But that’s awful,’ she said, ‘really awful. Oh, I am so sad for you.’

I felt tears well up in me. Unwittingly she had broken through the defensive wall I had so carefully constructed around me. I knew it was wrong, she knew it was wrong, but I didn’t know what to do about it. This particular boat most certainly did not need rocking. It would sink, and I would sink with it.

October 1980. Bonnie’s husband, an economist, was away on a business trip. Moya and I invited her down to ours for the evening so she wouldn’t be on her own. I offered Bonnie a pre-dinner drink and replenished it despite her protestations. She and her husband had recently returned from a trip to Sri Lanka. Bon said she had found the atmosphere there almost erotic. The sultry heat, she said, and the people walking so languidly, their hips swaying and their loose clothing swaying too, men and women alike.

I don’t know about bloody Sri Lanka, but hearing Bonnie talk like that was pretty damn erotic for me. My imagination soared and the thought of Bonnie becoming aroused, combined most certainly with a strong scotch and soda, brought a crimson heat to my face which I made no attempt to conceal. I probably spent the rest of the evening grinning like the proverbial Cheshire cat. After all, I was in close proximity to a calm, softly spoken, gentle woman who had begun to fill my waking thoughts, and most of my nightly ones as well.

Some time around the middle of the evening, the heavens opened and the rain came bucketing down. It pounded on the roof and we could hear it splashing off the pavement outside. Throughout the evening, I made sure Bon’s wine glass was never empty, although I noticed she wised up to this quickly and never had more than a sip or two before I wielded the bottle again. Finally she said she ought to get back home and relieve the babysitter, who was looking after her two children. My wife nodded. Then she said, and these were her exact words, ‘John, you’re not going to let Bonnie walk home alone, are you, in this pouring rain? You must go with her.’

I swallowed hard. ‘Of course,’ I said, as a thousand butterflies suddenly took flight in my stomach. I remember the feeling. If this had been a movie, the camera would have caught the smug smile of satisfaction as I realised this was the moment I had waited for for so long. In fact, the feeling that filled me was closer to panic. What should I do? How should I behave? What if, in the next few minutes, it became transparently clear to me that Bonnie had no more feeling for me than any other bloke she had come into contact with? The illusion, the fictional edifice I had built, would be fatally breached and come tumbling down.

Oh Lordy, oh God, oh Hell, I thought as I took the umbrella my wife handed to me. We stepped outside, the two of us, making small exclamatory noises as the rain hit us. Bonnie took a hurried couple of steps to the gate before I could get the umbrella up. Rejection. Obvious. Fool. I hurried after her and onto the pavement. She waited for me to catch up. Ha! Good sign. Or not. The street lamp lit up her face as she half turned, the rain soaking her and drops rolling down her cheeks. She was smiling a wide smile.

‘Here,’ I said, ‘come under the umbrella.’ I raised it over her head and in a move that seemed as natural as breathing, I put my arm round her. She allowed me to draw her body closer to me. We walked that way up the slope to her house, in step with each other and laughing like teenagers. We reached the back door of her house. A dim light came from inside, but apart from that we were in darkness. The overhanging roof gave us slight shelter from the rain, but not much.

I put down the umbrella and reached out to her. Her arms reached out to me. We took a step towards each other and our lips locked in a moment of the most intense passion I had ever felt. We kissed as though our lives depended on it. I parted her lips with my tongue, she responded and she pressed herself fully against me. I tasted her, inhaled her scent. I stroked her body with my hands, feeling up and down her back, the indent of her waist, then, gently, the contours of her front. She made small gasping sounds, seeming to crave me as much as I craved her. I felt her hands on my back, my neck, my head.

I don’t know how long that immortal first kiss lasted. Minutes, certainly. In the movie I would have told her how I loved her, how I had longed for her, how I had waited for this moment. She would have sighed ecstatically, returned my ardent words, probably to the strains of Rachmaninov. In fact, we said nothing. Our eyes held each other for a few moments. I picked up the umbrella and walked back down the slope.

I have thought about this moment a million times in the more than 30 years since it happened. Bonnie and I have talked about it, laughed over it. It has always led to a repeat performance. Today, as I write about it for the first time, it only brings tears to my eyes.

Bonnie is pacing round the house and I want to tell her what I am remembering, but I don’t. Why talk of something that will mean nothing to her now, and might make her regret that she can’t remember it?

But can I really be sure it will mean nothing to her? What if I am wrong, and she does remember it? If she does, it will bring her a lot of pleasure. I decide to test it in as gentle a way as I can.

I go out onto the terrace, and of course Bon follows me out there. We stroll around for a few moments, then I lean against the table and say, ‘Come here, darling, come here a moment.’ ‘Why?’ ‘I want to ask you something.’

She walks towards me and stands facing me.

‘Do you remember our first kiss?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘When was it?’

‘Er…I don’t know.’

‘Take a guess.’

‘Five years ago?’

‘Yeah!’ I say, raising my arms in triumph. She smiles with satisfaction.