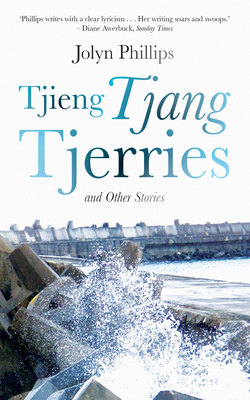

Читать книгу Tjieng Tjang Tjerries and Other Stories - Jolyn Phillips - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Photograph

Оглавление‘I am. I am. I am.’

‘Yes!’

‘Issie, Liesie, my toe didn’t even touch the line.’

‘Is Jonie. You’re out!’

‘But–’

‘Ha a nee, you’re out. It is my turn!’

Marelize and I were arguing about whose turn it was to play hokkie when Antie Pyma Hinkepink came through the yard. I was watching her hobble past us towards Antie Molla’s house and in my head I sang to the rhythm of her walking:

Antie Hinkepink

One two three

Washing everybody’s dirty laundry

Five six seven

The dog runs loose

Seven eight nine

Her man is goosed

And her poor children cries ‘There’s no more food’.

Antie Molla was in the kitchen, I could see she was watching us playing through the window. Why is she looking at us like that? I thought. First she was looking at Antie Pyma, then at me, and then with her hands over her mouth. Then at me again. Antie Molla knocked on the kitchen window with her eyebrows pulled skew. Any child knows that means: ‘Get inside, or else …’

I was too busy looking at all the women from Dahlia Street, Skool Street and Roos Street running towards my street, and I wanted to run with, to see what was going on. I was just about to skedaddle when Antie Molla grabbed me by my collar.

‘In met djou,’ she said, ‘daai is grootmensgoed, you and Marelize must grate polony for the kosbakke.’

I smiled because I knew she only cared, even though sometimes she came across as strict. Sometimes I would ask Liewe Jesus if I could trade my ma for Liesie’s Ma. I wished I had such a nice Ma like hers. Ma Emmie said she is a weglê-eier from a white man. She has pitch-black hair like Sneeuwitjie’s and she wears her hair in a long vlegsel that hanged like a horse’s tail behind her back, and she is not brown like us, she was amper white like a real Boer.

I liked An Molla’s house. It was always full of laughter and they liked singing for Jesus and on Fridays, I would go to youth practice, and wear skirts and doekies that you tie like a bolla behind your head. Best of all is, they always had milk and Coke in the fridge, not like in our house where we drank powder milk in our cereal because Ma said milk was for madams and queens and we weren’t either. Sometimes An Molla even asked me to comb her hair when she came from work at the fish factory. I combed it carefully and handled it like something precious. Her hair always smelt like Colgate Apple shampoo. Afterwards, when I got home in the evening, I untangled my hair and combed it out and imagined I had hair like hers, but mine was brittle and kroes and had never grown past my ears.

My head was full of thoughts and the polony I was grating with Liesie just rested there. How was I supposed to help Liesie grate polony when Antie Molla looked at me the way she does when something bad happens in her favourite soapies? Through the window I saw her cross the street to join Antie Pyma and the others outside our house.

‘Your mother is looking for you,’ said Antie Molla, entering through the kitchen door.

‘Ma, my ma knows I’m sleeping over,’ I said, dikbek.

‘Man, moetie teëpraatie,’ she said, her voice a bit louder this time.

I nodded my head while I looked at my dirty feet, ash gray from all the games we played today. I was a bit sad that I couldn’t sleep over, but I would never answer back to big people.

‘Naand Oom Friekie,’ I said in a low voice. ‘Naand almal,’ I greeted everyone in the sitting room watching Bold and the Beautiful.

When I got home our whole yard was full of people. Even people from HOP Land were there. It is probably that stupid brother of mine, I thought to myself. I wish he would just disappear, but Ma mos always take his side. I felt that she forgot that I’m also her child. As I walked through our yard, everybody was whispering behind their breaths. Agies, I thought. They like gossiping about us, because Ma and Derra are always fighting, because he is always drunk. I stood in the door and watched my ma sob really loud while Antie Zin and Antie Kêtie comforted her. Ma was looking at the ceiling mumbling, ‘It’s not him, it can’t be him.’ I was so confused because everyone gave me that I’m-sorry look, but no one said a thing. They just watched my ma cry.

I did not go to school the next day. Ma was up early, cleaning and turning out the house. The house became quiet, that made me feel restless so I got up. Our house is made from siersteen bricks, a fabriekhuis, an ‘opskuldhuis’, Ma would remind Derra. I could see the living room from my room. Derra was sitting next to the CD player, listening to Kfm, with his head almost resting on his lap. Ma returned from An Griet, the Funeral Antie. The moment Ma came home, she just looked at Derra, but their eyes were screaming, ‘It is your fault!’

Later on I decided to go to Derra because I felt bad for hating my brother for dying. ‘Derra?’ I asked.

‘Yes, Jonie?’ he said.

‘Is Derra and Ma angry at me?’

‘No kint, this is not about you.’

He did not look at me once, like me being there made it worse. I knew he was lying to me. I left him there and went back to my room that Ma had cleaned by now, sweeping and dusting like her life depended on it. I lay on my pillow with my head at the foot side like Ma when she thinks about everything, hugging my teddy so tight almost like that would make it hug me back, but I became restless and so I walked passed Derra very quietly and pushed my bike out the tool hokkie.

As soon as I got on the bike I pedalled so hard it felt like I was riding on the wind up Ridderspoor Street, Lelie Street and past Beverly Hills Plakkerskamp. The closer I got to the shore, the more I could smell the fynbos, making my nose tickle a bit, and the smell of the sea, so familiar. It lingers in your lungs like the early morning mist resting on our roofs. The sea was my only sure thing. My backpack started to wriggle. I knew who it was. I was in such a rush, I took the bag my dog Suzie likes to sleep in. My back was wet and so was Suzie’s tail, shivering like jelly. I walked towards the shore to wash my shirt. The sea seemed angry that morning, the waves did not tumble forward and calmly rest on my feet like other days. She pushed forward a lot of bamboes, always a bad sign. I soaked my shirt in the water. I looked down at my body.

I am the only one that doesn’t have tieties in my class. My older cousin told me that if I put chicken stront on it, it would grow faster. I put my shirt carefully on a rock and Suzie and I baked in the sun. I smiled because it felt like the sun was hugging me, and Suzie licked me on the nose. She knows when I’m sad. She loves me the most, just like that moment, quiet and calm.

When I got home I gently rested my bike against the wall. My aunt, Antie Ragel, was waiting for me. She grabbed me by the ear. ‘Liepe Heiland! Waar was jy? Jou ma het genoeg om haar oor te bekommer, gat in da so!’ my aunt scolded.

I ignored my aunt while I took Suzie from my backpack. I wanted to see Ma, I was sad and Ma always knew how to make me happy. I was scared and it felt like our house was swallowing me. I walked in on her unpacking my brother’s closet, then packing the clothes back again. I didn’t know what to say. I just leaned my head against her shoulder, but she pushed me away. She looked at me very angry, her eyes and her glasses misty.

‘Go play outside,’ she said.

I stood there frozen, giving her a dead stare.

‘Get out!’

That was ten years ago and I still feel like that little girl when I come home to visit Ma from college. Nowadays Ma looks old. Her face is small and tired. I do not recognise her any more. Everything about her irritates me. She snaps at everything I do and sometimes she just comes to my room and looks at me. I hate being here with her and our life. The house no longer smells like Jik and washing powder. The walls have turned yellow from all the cigarette smoke and the white ceilings are dotted with specks of mould. It reminds me of stale bread. As a child, Ma would always tell me that stale bread gives you a nice voice. I see the cups are half washed and the cupboards are almost empty, just a bottle of fish oil, flour, a packet of yeast and pot of salt. The fridge is switched off and stands in the kitchen like an ornament. I am standing at the door observing our street, it is still as busy, with neighbours doing washing and gossiping.

‘Oumatjie! Jonie! Jonie Felicity Gibson! Antwoord tog?’

It is Ma calling me. I walk towards my room.

‘Ja Ma. What is it?’

‘Don’t come and what me. I am still your mother.’

She is scratching through my things. Sometimes it seems like she looks through my things hoping to find me there. She completely ignores me watching her go through my things. In my mother’s house, there is no such thing as private.

‘Look what I found!’ she says excitedly.

She gives it to me. It’s a picture of my brother and me.

‘He was darem a beautiful child,’ she says, smiling.

‘Ja.’ I say, ‘Ma se oogappel’ in a resentful way.

She turns with her hands making fists in her hips, ‘Haai! No child, I have never treated you children like vis en vleis.’

I look at Ma sitting with her legs crossed on the tapyt floor laughing at the picture. I can’t help but join her.

‘Look Oumatjie,’ she says, ‘it’s you! Always a koddige kint.’ She sighs. ‘You know, when you were born you were so small you could fit into a shoebox. Pa said that it was a blessing, such children become clever children. Ai, that man was never wrong. Ma Emmie was very concerned. She was too scared to hold you. “Oe gotta kintjie, gat die dingetjie lewe,” Ma Emmie peeped. ‘You were two years old,’ she goes on with a smile on her face, the same sort of smile that I imagine she would have had the day the photo was taken.

‘Look, Antie Giena, she looks drunk,’ I say.

‘Yes,’ Ma says, ‘she is the biggest holy clown in Aster Street now. And there is Old Jim too, I miss the old devil.’

‘Why did they call Old Jim a duiwel?’

‘Loved women,’ she says simply. ‘And here stands Pa, your oupa,’ she continues. ‘Pa loved you, spoiled you rotten, tot in die afgrond in. I remember this one time, you were just starting to crawl, and we were living by Koekie-them on the hill when you fell off the blerrie steps. Pa could only think of one person to blame …’

‘Wapie!’ we say together.

‘When I got home the poor child was in tears and on top of that Pa only bought sweets for you, so I had to run to Andries Kafee to get Wapie some with my last pay. You know he really did love you, your brother,’ she says. ‘He would abba you on his back. The day I brought you home he looked at you all the time with his little legs hanging from the bed kicking, and he’d kiss you on your little forehead.’ She goes on talking. ‘Ai,’ she says, ‘you mos remember Annie Têtjiebek, nè?’

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘that lady with the voice that sounds like a hooter.’

‘That one looked after you,’ she continues, ‘she only worked for me for a week. I was so thankful at the time. I couldn’t stay home any more, you mos know your pa was drinking, as hy mos syp, dan syp hy sy werk onder sy gat uit. I nogal paid her R20, die bleddie fool,’ Ma says. ‘Then one day, I come from work and as soon as I put my bag down she starts scolding like a crazy hoenner. Annie says, “This damn klimeidjie tells ME that I’m too drunk to look after HER, can you believe it? Dè,” she says, “take your fokken kint, I will get my money later. Bye!”’ Ma laughs as she tells me about Annie.

‘What did I say?’ I asked, laughing.

‘You loved counting teeth. You must have overheard me talk to Giena,’ she says.

‘Ma, uhm, do you still miss him?’ I ask.

‘Who?’ she asks, fixing her eyes on the photograph like she is trying to copy every detail in her mind.

‘Wapie.’

‘Ja.’ She says, ‘I miss you,’ stroking my face and Wapie’s face on the photo.