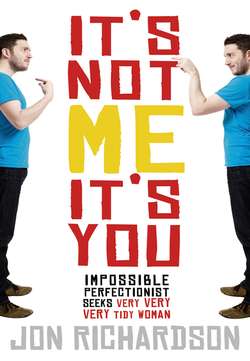

Читать книгу It’s Not Me, It’s You!: Impossible perfectionist, 27, seeks very very very tidy woman - Jon Richardson - Страница 5

SATURDAY

11.39

CLOSE EVERY DOOR

ОглавлениеI definitely remember dropping a bin bag half filled with rubbish into my wheelie bin on the way to my car. I remember putting my suitcase in the boot, beside my emergency box and climbing into the driver’s seat. I turned the key in the ignition – I remember that because the radio came on and they were talking about rap music so I turned it straight off – and then I pulled out of my driveway and on to the road. After driving about two hundred metres I signalled left – though nobody was behind me – and pulled over to the side of the road, stopped and applied my handbrake. This is where I have been for around three minutes now. It has started.

Did you lock the door?

The trouble is that while I’m thinking about whether I locked the door, I’m also thinking about Gemma.

I cannot stop thinking about her, which is a problem. I am certain that she would absolutely hate it if she knew what I was doing now and I do not want her to end up hating me. I just don’t know how you explain this kind of thing to someone who could never understand living this way.

It is an unfortunate fact that you have to have once loved someone to even begin to be truly capable of hating them. People often say that they hate certain comedians but they don’t really – they just don’t like their jokes or else are jealous of their success. I don’t mind someone saying they hate me when I know they don’t know who I am, but I can’t bear someone who once loved me pretending that they don’t hate me when I know they do.

But … did you lock the door?

Why does this always have to happen? It isn’t just when I drive – I can be on foot or even with other people. One of my lowest points was asking a taxi driver to return to my house halfway along our journey to the train station so that I could be sure I had locked the door. I can still hear the surprise in his voice now: ‘Go back, mate? Really?’ I told him I had forgotten my passport so that he wouldn’t think I was weird, but I felt bad anyway. Having to invent a fictional short-haul trip to France to cover the fact I had so little luggage with me was no mean feat either. Step forward the fictitious ‘sick relative’, no more questions asked. Besides, he was glad of the extra fare, I am sure.

My fear comes from years of living alone, with no one but me to take responsibility for my mistakes. If I don’t do something, it doesn’t get done – it is as simple as that. I absolutely refuse to go back this time though, no way. Things have changed. Each day I retrace my steps a number times, to check whether or not doors and windows have been locked, fridges closed, lights turned off, and each time I do so I find that I’ve always done what I thought I hadn’t. I have to accept that I am a worrier and I do not forget to do things like locking the door – that is what other people do, people who aren’t trying as hard as I am. But then again perhaps I have lulled myself into a false sense of security this time. Perhaps this time the door really is unlocked and I will be making a mistake if I don’t go back. It would be worse to have stopped and decided to carry on than not to have considered the possibility at all. Once my neighbour knocked on my door to tell me that I had left my car window down, so I am unreliable. Admittedly it was years ago now and nothing bad happened as a result, but still it sows seeds of doubt in my mind – you only have to fail once to be a failure. If I wait here any longer I will have wasted as much time as I would have by going back to check whether the door was locked after all. I have to make a decision.

I think you left it open, because you rushed down the driveway to put the bin bag in the wheelie bin and forgot to go back and lock the door.

Now, that seems plausible; I absolutely could have done that. A few net curtains twitch around me to remind me that I am disturbing the order of things, as if the houses themselves are winking at me in sly warning, like a Cockney down a dark alley, though in truth it is simply the inquisitiveness of the people behind who have nothing better to worry about than whether a stranger is in their midst.

I have lived in Swindon for five years now, and to me it is something of a Goldilocks town, in that it is just the right size for what I need. If it were any bigger, decision-making would be rendered utterly impossible by having too many options for which shop/restaurant/ post office to use. Equally, any smaller and it would make impossible the chances of disappearing into a shapeless crowd when out and about.

This is a town where you might recognise faces but never need to know names. The kind of place where you can be ‘the guy who is always in the chip shop at the same time as me on a Friday’ but need never become ‘Alan, who is married to Sarah, who used to work at the Cash and Carry but lost his job because he was caught sniffing women’s shoes in the changing rooms so now works from home but really is supported by Sarah because he’s too embarrassed to leave the house because he knows we spend most of our time talking about him and will do until something happens to someone else whose life need not affect us save for the fact we have so little else to talk about.’

People who have lived here all their lives will tell you that the traffic is bad or that crime is worse than it used to be, but those of us who have had experience of living in bigger cities will tell you that the traffic is rarely beyond manageable and, if you didn’t scour the local newspaper on a daily basis, you would barely notice the petty crime that goes on. I lived in Bristol long enough to see that Swindon is actually a fairly quiet place. I left five years ago because the people I was living with had seen too much of my weakness for them to have the respect for me I wish for. The city echoed with mistakes I had made and everywhere the memories of failures I made earlier made it difficult for anything to seem perfect ever again. I wonder if there will ever be a place I can foresee spending the rest of my life in. More likely it is me who will change; one day I will stop caring about the mistakes of the past. Hopefully.

Swindon is, I’ll grant you, an odd place to decide to build your utopia, but it seemed right at the time. House prices are as low as anywhere in the region, transport links make it an easy place to get out of and, most importantly of all, I don’t know anyone here. The door need never knock unexpectedly on a quiet Sunday and force me into a state of begrudging hospitality. I have a home phone, but no one but me knows the number. You might think this pointless, but I adore it. It makes the phone a talisman of my self-imposed isolation – I am like Willy Wonka, but I make no sweets and the closest I get to an army of Oompa Loompas is the occasional spider infestation. Oompa Loompa doopedy doo, I’ve got a Dyson hoover for you!

Most of the time I adore this solitude though I must confess that illness brings home with shocking clarity how, despite living in a large town and having neighbours on either side of me, it is possible to feel tremendously isolated by my choices. Recently a bad meat and potato pie sent me into feverish convulsions, my body going into full evacuation mode to rid itself of the pollutants inside. It was then that I became aware that there was nobody close enough to me to bring round warm soups, to mop my brow, or (in the worst-case scenario) discover my shrivelled up corpse on the bathroom floor. Twenty-eight is too young to be one of those people whose bodies lie undetected for weeks before questions are raised. ‘Here lies Jon Richardson. He died of a pie. Ashes to ashes, crust to crust. RIP.’

When I left my last home in Bristol, I thought for a long time about moving to the seaside, but I am not yet old enough to spoil that surprise. Like hearing Christmas adverts in October, nobody should live by the sea until they are old enough to appreciate it – its smells and its sounds. The sea is there to remind us what insignificant pieces of shit we all are. When you start to worry about death and how the world will cope without you, the sea roars its laughter down on the sands of your concern and tells you that it will be around long after you and was here long before you. You have to be old enough to appreciate this, having acquired the intelligence and perspective not to misinterpret this as a threat, rather than the arm across the shoulder it really is. ‘Don’t worry old friend. The sands over which you walk are made up of the very bones of things that once, like you, worried about what would become of them. Now you carry them away with you in your shoes and they find their way into the corners of your kitchen and bury themselves deep into your living room carpet. They have no more to worry about, but I am here still.’

I have always felt like the larger coastal towns had a latent aggression about them, almost as if the inhabitants were still worried about invasion by sea so walked around with broken bottle tops and concealed knives just in case. Because of the prevalence of old people seeking to die with sand in their socks, the young, for fear of being typecast as living in a glorified nursing home, start drinking blue drinks as soon as they finish work and take drugs as if to prove to ‘them London fuckers’ that they know how to have a good time, too.

The sea, however, doesn’t care. No matter what they do to try and impress it or repel its advances, it lurches forward and eases back with comic consistency, as if it is playing a game of chicken with those who live inland; a show of power that one day, if they look like they have forgotten to flinch, it might not retreat as soon as it should.

Of course not all elderly people retreat to the sea in their final years. There is an elderly couple who live on my boring little street in Swindon and that makes me feel sorry for them. It isn’t that we live in a particularly bad area, but just that it isn’t particularly nice either. It was built for people like me who could just about live anywhere, so long as it has four walls to put a bed and a toilet in. If Travelodge made towns, they would make Swindon. It does the job quite happily, thank you. Quite happily. Our local pub is a perfect example of this desire not to exceed sufficiency. It serves beer and has been built with aged beams to belie its newness, but it has none of the soul of a good pub. The ceiling would once have been white but has clearly not been repainted since the smoking ban came into place, and as such carries the trademark yellowy-orange patchiness. Perhaps I am wrong and the patchiness exists because the pub ends each night with a lock-in for selected clientele who sit around drinking ale and laughing heartily whilst smoking cigars, but I doubt it. People go there to do what they need to do, to drown what needs to be drowned and go home. Above the bar are a number of brass plaques engraved with playful re-imaginings of well-known phrases and proverbs.

‘A friend in need is a bloody nuisance’

‘Where there’s a will, there’s a dead relative’

And my particular favourite: ‘If arseholes could fly, this would be an airport’

Then, in the middle of the bar, right above the new and ostentatious pump for a well-known lager, which rises up like a serpent from the bar and seems to point upwards at the laminated piece of card, crudely printed from a computer in a number of different colours now faded with time:

The Customer is always Right. A Right pain in the Arse.

This last one doesn’t even really work – it is simply rude, another way of telling anyone on the wrong side of the bar that they are not welcome here. I don’t know why they don’t just go the whole hog and write ‘FUCK OFF’ in huge letters above the front door. Of course they are jokes, we can enjoy these signs because we are safe in the knowledge that we are polite and generous customers, and it is understood that the staff will be happy to attend to our every whim with a smile. Except that they aren’t, and we aren’t. The customers here are tired and rude, the staff not much better. It takes the gloss off the wit and all that is left is a sense of begrudging service.

Drink here if you must, but know this … I absolutely hate your guts. If you die on the property I will call for medical assistance, as is my duty, but should you fall even one pace outside my front door, I will simply laugh and be glad that you won’t be returning any time soon.

My street has no more character, with nothing to mark it out from any of the others around except for the words written on the signpost at the top of the road. All the streets round here are named after famous wartime actors. Classy. The houses are all identical and this ensures that the happiness of the occupants is entirely down to them. British people talk a lot about ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, trying to match your neighbours’ possessions: cars, hanging baskets, new windows. When the new-build houses are all identical it shaves off another layer of your potential individuality, which is absolutely fine by me.

There are clues as to who lurks behind the walls of the individual houses, if you care to look for them, such as the ostentatious pebbledashing of the retired couple down the road, keen to show that their wealth has not been hit by recent economic troubles. I have no problem with pebbledashing in the right place, but I’m afraid here it simply looks as though a drunk snowman has been sick all over their home whilst staggering back from the pub. Twice a year, at Halloween and Christmas, houses containing young children are made obvious by the volumes of cheap plastic paraphernalia that adorn the walls and front garden. From inflatable waving Santas to witches on broomsticks hanging from the guttering, the cartoon exteriors belie the misery and squabbling going on behind them. The children always look bruised from the inside out and the parents exhausted by what they are sure was once love.

And then there is my house. Plain and grey, there are no plants on the tarmacked driveway since I am never at home long enough to look after them. I have a wheelie bin, thank the council, and a little porch light whose bulb has never worked as long as I have lived there. I don’t get many visitors anyway, so it is of no use really. The point of moving to Swindon was to encourage me to make more of an effort to travel to see my friends and family who are spread out across the country, which I do my best to do, although it seems harder year on year to find time when days off coincide.

Swindon is a place in which I can exist in the meantime, drinking and sleeping. It’s not that I am unhappy here, just that happiness simply isn’t a factor. In the same way that you need the pang of hunger to appreciate full satiety, you need happy days in the park to appreciate the blues. There is nothing like that here, just people getting on with what they need to do and trying not to think about it too much. I don’t mean to make this sound depressing, because it isn’t really – it’s just the way it is. Cavemen didn’t waste their time thinking about whether or not they were happy or whether their lives had meaning; they were out hunting and trying to stay alive. We’re the same creatures – nothing has changed that much. We invented happiness when finding food became too easy and survival became the norm.

Once we could all get through the days without trying, we had to find some other reason to wake up each morning; we had to adopt a scoring system to see who was winning at being alive – happiness! Now we think about it all the time, we talk about it with our partners and we travel the world in search of it. I am playing a much longer game; like good comedy I believe the secret to be about timing. If I am too happy in my youth, then my senior years will surely see me unhappily lamenting the passing of the life I once had. If, however, I maintain a level of enforced melancholy for as long as possible, then I can escape into retirement rather than be forced into it. If the last day of my life is the happiest, that will suit me just fine.

As I ponder this point, a miserable-looking old woman walks by my car with bags full of shopping and stares at me as she passes, distrustful of why I am parked on her street and completely unaware that I live just around the corner. Her latent hatred of me is typical of almost everyone I encounter here. My neighbours, I am quite sure, suspect that I am a serial killer, a view I am quite happy to promote whenever I get the chance if it keeps them from talking to me, be it with a well-timed sinister chuckle to myself, or by making sure that they see how meticulously I clean the interior carpets of my car.

I must point out at this juncture that I am not a killer, though I have often thought about it when in crowded cinema screenings or on public transport – but who amongst us can honestly say that they haven’t? There is no reason for them to think this of me, save for the fact that if you asked them to describe my character they would most likely tell you any combination of the following:

1. I am polite

2. I am hard working

3. I am always well presented and meticulous

4. I keep myself to myself

5. I wouldn’t say boo to a goose

As any viewer of late-night crime documentaries will be able to testify, this is a classic serial-killer profile. It only takes a few bad pennies to ruin things for everyone and it’s thanks to the likes of Jeffrey Dharmer that men like myself are eyed with suspicion wherever we go. I am no saint, of course, and willingly confess that while I may not have said boo to a goose, I did tell a swan to ‘fuck off’ during a walk in the Lake District a couple of years back.

The car’s fan kicks in as the engine has been idling for too long now and my mind is turned back to the issue in hand. The problem, you see, is that taking the rubbish out is a rare event since I spend so little time at home, and so I am apt to remember doing it. Locking doors, however, is something I do all the time, so each individual occurrence blurs into an obscurity of infinite replicas. Perhaps if I mark out each time as unique by saying something memorable as I do it, it might stick better in my memory:

‘Jon Richardson is locking his front door in the rain and he had Shreddies for breakfast. Boobs.’

That kind of thing would be memorable. This is what I will do from now on, but this time I am just going to drive and when I get back tomorrow and find that the door was locked the whole time, I will treat myself to a smug, self-satisfied smile and know that I am getting better at life. In weeks and years gone by I would have gone back to check, but that was when I didn’t have Gemma to think about.

Gemma is the reason I am trying to be more normal, because I imagine that’s what she wants me to be. The best dating advice I can give you is that women like men who aren’t weird – and, I suppose, vice versa – and that’s probably where I have been going wrong for the last eight years. I am not a particularly attractive man, shorter than I would like and with too round a head to feel entirely comfortable when walking past a tennis court, but nor am I ugly enough to warrant the eight-year suspension from the opposite sex that I have been serving. My voice is rather too shrill and I tend to moan too much, but I suspect the main problem has been things like checking doors and getting uncomfortable because I feel that I have stepped on more cracks in the pavement with my left foot than my right – that’s what has marked me out for singledom. No one wants to walk the streets arm in arm with a man who occasionally breaks free to cross the road and step on a grid to ‘even things out’.

Having someone else to think about once more holds a light up to some of my more eccentric behaviours and I can see that parking by the roadside, yards from your house, and sitting in a catatonic state is not right. Life is about simply playing the odds and I have to concentrate on making myself a reliable target for love. Gemma and I are normal people and we go about our business normally, thinking about one another all the while. Besides, who would call at my house even if the door were unlocked? Swindon and its total isolation wins again!

Mirror, signal, manoeuvre. As I finally set off to my gig, I sing a song of victory to myself, a victory over the old me.

Hit the road, Jon, and don’t you go check that door.