Читать книгу Woodworker's Guide to Veneering & Inlay (SC) - Jonathan Benson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Veneering Then & Now

A wood veneer is an attractive but thin slice of wood that can be glued onto a furniture surface or wall panel, creating a rich look for very little expenditure of expensive material. Veneering is an old process that has changed and developed along with advances in wood processing and cutting. Historically, veneer was used to decorate the very finest furniture; in recent times, it has also been used to disguise some of the worst. Today, it is still possible to produce very fine veneered furniture using basic woodworking tools.

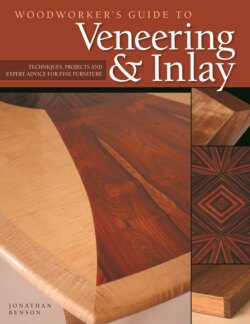

Desert Sun Sideboard by Jonathan Benson combines vintage Brazilian rosewood, curly maple, and ebony veneers. The 36" x 62" x 22" sideboard was created using the simple tools and techniques covered in this book.

Historical background

Veneers have been used in woodworking for more than 5,500 years. Examples of veneered pieces dating back to at least 3500 BC have been discovered in the pyramids of ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphics and frescoes created around 1950 BC depict workers cutting, joining, and gluing down sheets of veneer using stones as weights for clamping. The veneers were cut with an adze, a tool resembling an ax with its blade turned perpendicular to the handle. This process produced veneers that were rough, uneven, and about ¼" thick.

As technology progressed, it became possible to make thinner veneers. In Roman times, an iron-bladed pit saw was used. One worker stood in a pit below a log while another worker stood above, each pulling opposite ends of a large saw. The Romans also developed smaller bow-type saws, which could be used by one or two people. Sawn veneers could be much thinner than adzed veneers, close to ⅛" thick. Like adzed veneers, these early sawn veneers remained uneven and required much leveling and smoothing to create an even surface. Because these processes were labor intensive, veneers could only be used in the highest applications.

Figure 1-1. A 48" x 22" x 12" Art Deco chiffonier in curly maple is a classic 1930s Ruhlmann reproduction by Pollaro Custom Furniture Inc., Union, New Jersey. (Photo courtesy Frank Pollaro.)

Figure 1-2. A wet bar wall, made with quilted makoré panels and cabinets, pomele sapele bent-laminated doors, and a granite counter top, was designed by Dave Boykin and made by the three-man shop of Boykin-Pearce Associates, Denver, Colorado. (Photo courtesy Dave Boykin.)

Just like craftsmen today, early craftsmen had good reason to go to such trouble to fabricate veneers. In ancient Egypt, fine woods of interesting and contrasting figure had to be transported great distances, making them scarce. Cutting the wood into thin layers enabled it to cover more surface area. Also, rare and highly prized burls, large knotty growths found in many species of woods, will check, crack, and warp unless sawn very thin (Figure 1-3). Additionally, thin woods can be arranged and combined in intricate patterns, regardless of grain direction or species, without problems due to wood movement (see Chapter 2).

When circular saws came into use during the Industrial Revolution, veneers of 1⁄16" could be produced in large quantities. Veneer began to be used on a much greater scale. More people than ever before could own these inexpensive, mass-produced goods. Unfortunately, at this same time, veneer came to be associated with cheap, shoddy construction. The idea of a fine veneer covering over a cheap interior has been associated with the process ever since. Dictionaries today define veneer as “to disguise with superficial polish” or a “false show of charm” (Webster’s Dictionary, New Edition).

Figure 1-3. Ziggurat Chest of Drawers, 60" x 24" x 18", by furniture artist Silas Kopf of Northhampton, Massachusetts, features burl veneers with mother-of-pearl inlay banding. (Photo courtesy Silas Kopf.)

The middle class grew tremendously as labor shifted from working the land to working in factories. Technology continued to advance and veneer became ever thinner. With the incorporation of the mechanized knife in the early 20th century, veneer could be sliced to ⅓2" or less. (Today, most U.S. veneer is 1⁄28".) This was a huge advance in the efficient use of woods. The veneer was cut thinner, allowing it to cover more surface area, and the saw kerf (waste from the thickness of the saw blade itself) was eliminated. Far more veneer with a matching pattern could be produced, allowing for the coverage of larger areas, including entire rooms (Figure 1-2), with the same uniform pattern.

Then, due to the popularity of exotic woods during the first half of the 20th century, some of the finest furniture being produced was made using veneers (Figure 1-1). Consequently, during the last 200 years, veneer has lived a dual existence as the best and worst that wood furniture design has to offer. Contemporary furniture artists have again turned to veneer for both the beauty and luxury it offers as well as its economy and practicality (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. A very practical set of three nesting tables by Jonathan Benson combines purpleheart veneer with stained curly maple turnings (20" x 26" x 20"). Although it might have been possible to make the curved side panels in solid wood instead of laminated veneers, the cost would have been prohibitive.

Advantages of veneer

With the rapid rate of deforestation and the near disappearance of an increasing number of tree species, use as veneers may be the only alternative left for many types of woods. Already, many species and rare figure configurations are only available in veneer form (see here). Some exceptionally rare species, such as premium-grade fiddleback makoré, may only appear on the market as one or two large veneer logs every few years.

The yield advantage of using veneer is tremendous. Take a given log and rough-cut 1"-thick boards from it. The lumber, dried and planed on both sides, yields a ¾"-thick board that will cover one square foot of surface area for every board foot of lumber sawn. Take the same log and cut it into 1⁄30" to 1⁄40" veneers, and it will cover 30 to 40 times as much surface area. Considering that, per square foot, the retail price of 1"-thick lumber is often only two or three times the cost of veneer, it is obvious why the best logs go to the veneer mill.

There are also environmental advantages to consider. Less lumber grown in tropical rainforests is needed to cover the same surface area when sawn as veneer. Renewable and waste materials, including recycled industrial waste, can be used as a substrate (see Chapter 4, here). Many companies are starting to use non-toxic, soy-based glues to manufacture particleboard, fiberboard, and plywood, all of which can be used as veneer substrates.

But the visual advantages of veneer may be the most important to designers. Veneers make it possible to combine different woods in an infinite number of ways, regardless of grain direction. That makes them “omni-directional”—both movement across the grain and movement due to differing densities of various species are eliminated once the veneer has been properly glued down to the appropriate substrate. The veneer is just too thin to move in any direction, regardless of seasonal weather changes. The idea can be taken to beautiful extremes, as in the pictures created by marquetry and the geometric patterns of parquetry (see Figure 1-5, for example). In addition to marquetry and parquetry, veneer patterns commonly include book-matching, four-way matching, and radial matching. In book-matching, the leaves of veneer open like a book and the pattern reverses from one leaf to the next. In a four-way match, the book-match occurs both side-by-side and top-to-bottom, like a folded piece of paper. In a radial match, triangles of matched veneer fit together around a common center like a sunburst. More complex patterns are based on the three basic ones.

Figure 1-5. Silas Kopf: Tulips and Bees side table (54" x 20" x 35") combines marquetry in the floral doors and the bees, with parquetry in the assembly of blocks containing the bee motif itself.

Figure 1-6. Treefrog Veneers manufactures a variety of exotic-looking laminate sheets to be used like wood veneers.

Figure 1-7. The curvy base of Jonathan Benson’s W Table is made by bending and gluing fiddledback makoré veneer and combining curly maple elements (17" x 44" x 22").

Figure 1-8. Veneer is flexible and can easily be laminated into curved furniture forms. Constructivist Coffee Table, by Jonathan Benson, includes walnut, cherry, and granite (17" x 44" x 22").

Newer veneer materials, which can help conserve precious tropical lumber, are always coming on the market. They are made from less scarce and sustainable species of wood, as well as from synthetic materials made to look like rare woods. Other products have intricately patterned surfaces that do not resemble wood at all and can be produced in almost any color. Some have a herringbone or other pleasing pattern. The materials can completely change what a wood surface looks like, and are applied in much the same manner as traditional veneers, often combined with other wood veneers and solid wood (Figure 1-6).

Because a sheet of veneer is extremely flexible, all of the patterns, book-matches, and inlays discussed in this book can be applied to curved surfaces (demonstrated by the curved mirror project in Chapter 12). In fact, modern veneer gluing and pressing techniques make it relatively simple to veneer over curved surfaces, as well as to create curved pieces made entirely of veneer (Figures 1-7 and 1-8).

Figure 1-9. Dining Table by Jonathan Benson is made of holly wood and Swiss pearwood veneer, stained and painted wood, and glass (56" x 28").

Figure 1-10. Sideboard by Jonathan Benson is vintage Brazilian rosewood veneer and curly maple with tambour doors (36" x 50" x 18").

Figure 1-11. Jonathan Benson’s Pyramid Pedestal (37" x 15" x 15") has a bubinga base, vintage African satinwood sides, cocobolo and bubinga trim, a granite top, and a light to illuminate the gold-plated capstone made by jewelry artist Matha Benson.

Figure 1-12. Hall Table by Jonathan Benson features fiddleback makoré, curly maple, and glass (32" x 48" x 18").

Figure 1-13. Samovar Wall Shelf, with holly and Swiss pearwood veneers by Jonathan Benson, combines painted and stained woods (36" x 56" x 12").

The ability to properly handle, cut, match, and attach veneers can open up an entirely new range of ideas to woodcrafters of any skill level. At the same time, a lot of wood can be saved by using veneers. Most of the veneering processes covered in this book do not take a huge investment of either shop space or money. A small shop or an individual can go a long way using the basic tools most woodworkers already have. The addition of a screw-type or vacuum-bag veneer press opens up even more possibilities (see Figures 1-9 through 1-16). I will also cover more complex and production-oriented processes for shops that do a lot of veneer work. Anyone with an interest in veneering can start with some of the basic processes and move on to the use of more sophisticated tools and techniques as needed.

Figure 1-14. Sidetable by Jonathan Benson features fiddleback makoré, stained and bleached woods, curly maple, and a glass top. (30" x 30" x 18").

Figure 1-15. Hands of Time tall clock, by Jonathan Benson, is made of purpleheart and curly maple (62" x 26" x 12").

Figure 1-16. Pedestal by Jonathan Benson is made with pomele sapele veneer, maple burl, and a marble top (43" x 15" x 15").