Читать книгу Civilising Grass - Jonathan Cane - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction:

The Lawn is Singing

There is a way in which the dryness of the winter veld, when the sun is very harsh and the grass is bleached very white, or else is very black from veld fires, corresponds to the tonal range of a white sheet of paper and charcoal and charcoal dust – in a way more immediately even than oil paint. There was a way in which the winter veld fires, in which the grass is burned to black stubble, made drawings of themselves. You could rub a sheet of paper across the landscape itself, and you would come up with a charcoal drawing.

— William Kentridge, ‘Meeting the World Halfway:

A Johannesburg Biography’

William Kentridge (2010) observes that for much of his childhood in Johannesburg he felt that he ‘had been cheated of a landscape’. He explains that he wanted a landscape of ‘forests, of trees, of brooks’ but instead he had ‘dry veld, beyond the green gardens of the city’. The ‘veld’ is a particularly South African notion. Originally a Dutch word meaning ‘field’ or ‘countryside’, in Afrikaans it describes a field, pasture, plain, territory or ground, and in South African botany it is used to describe a set of vegetation found in southern Africa.

I felt this too when I was growing up in Johannesburg – without a landscape. I recall sitting in the back seat of my parents’ car watching fires burn across the winter veld, casting palls of smoke across the highways. I longed for green. I remember dreaming of planting lawns over the mine dumps and along the so-called green belts. The same fires would also burn the open grass veld next to our home, and the white men who owned homes in the suburb would beat the fire with sacks while my mother (and myself, when I had grown older) would spray water on the roof and lawns. Mostly, catastrophe was averted, but sometimes the fire would nick the lawn from over the precast concrete walls, scarring it black.

The lawn, consistently and perfectly mown, was a great joy to my father but also a cause for concern. On weekdays the gardeners – Laxton, after him Sam, then Benjamin and Hanock – would mow, fertilise, water, seed, spread compost and repair broken sprinklers. On weekends my shirtless father would mow his lawn. With the help of apartheid, my father’s family, who at the time of the Great Depression had been bywoners (white Afrikaans tenant farmers, displaced from their own property, often associated with ‘poor whites’), were lifted from penury and had taken on, with great commitment, the struggle to become ‘good whites’ (Teppo 2004). Among a number of other banal domestic practices that allowed them to lay claim to a viable white location, the lawn – its propagation, design, maintenance, appreciation and use – provided a territory and a backdrop for their (mis)adventures in white heteropatriarchy.

My mother, who during periods of my father’s absence energetically fulfilled his lawn duties, was Rhodesian, as were her parents. They too were committed lawn subjects, at home and on the sports field. Internationally successful sportsmen and women, they excelled in field hockey and lawn bowls. Indeed, I have many childhood memories of my grandparents, decked out all in white and padding softly on lettuce-green turf.

The banal brutality of these kinds of scenes has not been lost on careful artistic and academic observers.

The lawn in theory

Internationally, from the late 1990s onwards, critics have provided thorough treatments of the lawn phenomenon. The bulk of the research focuses on the United States, with some research from the United Kingdom and ex-British colonies.1 These studies put the lawn on the research agenda and opened up lines of inquiry into the lawn as a botanical, cultural, political and aesthetic object of analysis. The varied and interdisciplinary approaches have drawn on methods from environmental history, urban political economy, cultural history, urban studies, sociology and visual studies, producing a rich and provocative literature. These studies have done the hard work of tracing the histories of technological developments such as the invention and global spread of the lawnmower and the introduction and mass uptake of pesticides and fertilisers. They have asked questions about the meaning of the lawn; about the cultural values encoded in it; about how and what it signifies. Further, they have explored the lawn as a representational domain embodied in fine art, design, landscape architecture, architectural plans, advertising, ephemera, legal proceedings, poetry and so on. Some writers have also advanced a critique of the lawn from a Marxist standpoint, showing convincingly how environmentally destructive lawn economies structure supposedly personal landscape preferences. Notably, the discipline of political ecology has shown how lawns are part of a cyborg world – part natural/part social, part technical/part cultural – where non-humans play active roles in socio-natural processes. Finally, many studies have offered spirited political alternatives to the hegemony of the lawn while also acknowledging the powerful hold the lawn discourse exercises over the possibilities for speaking and acting against the lawn.2

As W. J. T. Mitchell formulated it in Landscape and Power, landscapes should be considered ‘verbs’, unfinished processes, inconclusive attempts at fixing a permanent vision of nature, rather than as ‘nouns’, which can be surveyed, owned or possessed. This theorisation attempted to address the way power functions in and through landscape, moving away from the notion that landscape represents power towards the idea that landscape is part of the operation of power. Drawing on Louis Althusser’s notion of interpellation, Mitchell suggests that the landscape is ‘not an object to be seen or text to be read, but … a process by which social and subjective identities are formed’ (1994b: 1). The landscape interpellates us, he argues; that is to say, the landscape is presumed to have the power to call out to us, to hail us, as Althusser put it, and in so doing it forms us as its subjects. This counterintuitive explanation of power shifts attention away from the presumed agency of individual selfhood to a structural reading of ideology.

Since the 1994 edition of Landscape and Power there has been something of a re-evaluation of the verb thesis. Historian Jill Casid (2011) has argued that while Mitchell’s ‘verb thesis’ contributed to a shift in thinking about landscapes as productive and active (especially with regard to imperialism and colonisation), it did not sufficiently consider performative accounts of power, nor did it account for the production of women, queers and disabled subjects.

In the preface to the second edition of Landscape and Power (2002: vii) Mitchell writes that given the chance to retitle the book he would now call it Space, Place, and Landscape. ‘If one wanted to continue to insist,’ says Mitchell, ‘on power as the key to the significance of landscape’,

one would have to acknowledge that it is a relatively weak power compared to that of armies, police forces, governments, and corporations. Landscape exerts a subtle power over people, eliciting a broad range of emotions and meanings that may be difficult to specify. This indeterminacy of affect seems, in fact, to be a crucial feature of whatever force landscape can have. As the background within which a figure, form, or narrative act emerges, landscape exerts a passive force of setting, scene, and sight. (2002: vii)

To understand this ‘weakness’, Mitchell suggests that it is necessary to take up the notion of desire: the Freudian/psychoanalytic picture of desire as lack or longing (2005: 61) and the image of desire as a process, an ‘experimental, productive force’ (Ross 2010: 66–67). It is the ambiguous formulation of desire as want that appears most productive in unsettling the power base of landscape. To ask what landscapes want ‘is not just to attribute to them life and power and desire, but also to raise the question of what it is they lack, what they do not possess, what cannot be attributed to them’ (Mitchell 2005: 10).

Casid’s response to Mitchell is evocative because she pulls in an entirely different direction, insisting on what she calls the ‘isness’ – the presence – of landscape by foregrounding its recalcitrance, its refusal to recede: ‘from landscape as a settled place or fixed point we instead encounter landscape in the performative, landscaping the relations of ground to figure, the potentials of bodies, and the interrelations of humans, animals, plants, and what we call the “environment” ’ (Casid 2011: 98).

The lawn is boring, it matters and we must say so

Casid’s response is an attempt to put landscape into action ‘under the performative’. She describes her project as ‘landscape trouble’ (2008), signalling a move to inflect landscape with the qualities of a verb to account for landscape as an ‘ongoing process of materialization’ (2011: 98–99). In response to Mitchell’s aphorism that ‘Like life, landscape is boring; we must not say so’ (1994a: 5), Casid retorts that, in fact, ‘landscape matters (and is volatile, fascinating, and queer in the ways it matters and performs); we must say so’ (2011: 100).3 The queering of the landscape is a theoretical manoeuvre that not only seeks to highlight the work of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) landscapers, gardeners, writers and artists but, further, seeks a critique of the very paradigm of heteronormativity, which dominates our ideas of ‘nature’. Queer theory suggests that so-called natural environments and processes of growth are not apolitical; they are caught up in a unidirectional narrative of progress and flourishing, which does not sufficiently account for the volatile, fascinating and queer in the ways humans and non-humans matter themselves. Casid’s performative conception also makes an aesthetic methodological stand against the primacy of landscape painting as the proper object of landscape studies and to include installation, performance art, sound, video and sculpture in the conversation. This is to reaffirm, in a different way, Mitchell’s refusal of landscape as a genre of painting in favour of landscape as ‘medium’ (1994a: 5). It is also to insist that landscape’s ‘performance’ is ‘not just taking place, making place, or decaying or even destroying place … but also and importantly its being and changing in and over time without final outcome despite the illusion of “isness” and the effects of naturalization’ (Casid 2011: 103). The ‘isness’ of landscape – its presumed presence as stable, as finished – requires the appearance of being outside of time, or after time.

Casid’s formulation suggests that landscape’s symbolic consolidation of power exists in an abiding paradox because landscape does not actually have a ‘final outcome’. The vitality of action, labour, process, movement in, on, through, by, in front of landscape is deeply threatening to the operation of the landscape idea, which is aimed at creating the illusion of permanence and stability. Landscape is always the attempt at transforming nature or land and the open-endedness of our relationship to these, into a space of ownership, possession, belonging; a stabilisation of the present and desired future formations of power into something seemingly permanent. In this sense, landscape must fail.

Scholarship should thus be far more interested in the disproportionate tendency to record, monumentalise and remember moments of success. Is it possible to claim that the imperial garden or, even more boldly, the imperial landscape (seen as processes and movements that are multidirectional and happening over time and space) is at its core already failing? Part of the ‘strategic instrumentality’ (Corner 1999: 4) of imperialist landscape is to arrest decay linguistically, aesthetically and materially, to present transient victories as evidence of permanence. The strategies of postcolonial, peripheral, queer landscape art and theory are to record the always failing garden/landscape as the norm, not the aberration, and to use failure as a tool of liberation. These minoritarian positions, the post-colonial and the queer, are concerned with life on the margins, and have seldom been under the illusion that ‘success’ belonged equally to (white) heterosexuals and (black) queers. Embracing failure as a liberatory approach, as proposed by Jack Halberstam in The Queer Art of Failure (2011), means reframing failure as ‘alternative ways of knowing’ and modes of ‘unbeing and unbecoming’ (2011: 23–24). These modes of flourishing and growing can potentially be outside of the time and space of productive, capitalist heteronormativity.

The lawn in South Africa

Six old white ladies with perms, in obligatory white bowling gear, cardigans and regulation flat-soled shoes, play bowls on a Saturday afternoon. It is winter, June 1980; some of the trees around the green have lost their leaves and it is likely that the East Rand Proprietary Mines (ERPM) bowling green is less than green – brown and dormant because of the cold, rainless winters that characterise the South African highveld. The highveld is a high-altitude plateau, especially in the north-east of South Africa, between 1 500 and 2 100 metres above sea level, which includes the Free State and Gauteng provinces, and portions of the surrounding areas: the western rim of Lesotho and portions of the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, North West, Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces. David Goldblatt’s Saturday afternoon: bowls on the East Rand Proprietary Mines green. June 1980 (1982; see Plate 1) is shot facing east; in the background is a double-storey terrace married quarters built by architect Herbert Baker in 1910 for the mines. If we look carefully, between the trees we see a distinctive Baker chimney, brick with a subtle flourish on the crown (Van der Walt & Birkholtz 2012). Opened in 1915 – just after Johannesburg’s oldest green, Kensington Bowls Club (1914) – the ERPM bowling green, like the gardens, fields and parks of Goldblatt’s photographic work In Boksburg (1982), appears both flat and ordinary, unremarkable.4 This banality is not incidental; neither is the flatness inconsequential. The flat lawn embodies centuries of expertise, hours of effort, substantial capital and a particular assemblage of desire and discernment.

As a photographer, Goldblatt was drawn to the boring and everyday, ‘to the quiet and commonplace, where nothing “happened” and yet all was contained and immanent’ (Dubow 1998: 24). In the everyday, he saw the conditions of possibility for apartheid’s insanity and brutality, and like the British Marxist art historians, cultural critics and geographers of the 1970s and 1980s who studied the ‘dark side of the landscape’,5 Goldblatt was drawn, repeatedly, to the seemingly innocent landscapes of South Africa. He made it clear that his interest in landscape had nothing to do with being a ‘nature lover’ but rather with ‘the way we act with the land, work with the land, move on it, mark it’ (O’Toole 2003).

The lawn is largely absent from Goldblatt’s earlier work, Some Afrikaners Photographed (1975). The images he captured there are landscapes of no-lawn; the Afrikaners he photographed do not seem to garden, or have gardens, but instead dance, work, farm, flirt, sing. In a later work, The Structure of Things Then (1998), the lawns seem terribly permanent, enduring topographies of apartheid. In Boksburg, his exploration of a segregated suburb, includes as many as twenty lawns. Both in the private garden and the civic sphere, these brittle black-and-white lawns form the grounds for polite, respectable white subjectivities. For instance, At a meeting of the Voortrekkers in the suburb of Whitfield, Boksburg records a team of ‘penkoppe’ (boys) and ‘drawwertjies’ (girls) squatting on the lawn with their leader. In a similar way, Flag-raising ceremony for Republic Day (31 May) at Christian Brothers College, Boksburg. 30 May 1980 depicts an everyday kind of political event, on a bleached Johannesburg lawn. In the domestic realm, Goldblatt observes kidney-shaped swimming pools rimmed with face-brick and lawn, precast concrete fences with neatly maintained grass, and, of course, mowing. In many of his photographs, the lawn is just caught in the corner of the frame. The tiny wedge of grass, bottom left in the photograph Girl in her new tutu on the stoep, is perhaps the most suggestive example of the lawn functioning in a supplementary, apparently unimportant way. Even in Saturday afternoon: bowls, where the lawn is in every practical sense necessary, even fundamental, it exists pictorially and ideologically as part of the background. The lawn seems to just be there.

It is the lawn’s just-thereness that explains, partly, why it has remained largely inoculated against sustained critique, why it has remained almost entirely politically unchallenged and is still ecologically, aesthetically and infrastructurally hegemonic.

While the lawn’s goodness, innocence and neutrality may have been convincing to most planners, artists and administrators, there have always been a small group of dissenters who have resisted the lawn in subtle and explicit ways, foregrounding the politics of its surface, offering alternatives to its dominance and taking a spade to its roots. For instance, in the eighteenth century Uvedale Price famously declared that the lawn was both boring and ugly, and entirely at odds with the picturesque principles that he felt were in good taste: ‘The notion that a lawn, or any meadow or pasture ground near the house, ought to be kept quite open and clear from any kind of thickets, has been one very principle cause of the bareness I have so often had occasion to censure’ (1810: 175).

In twentieth-century South Africa, at the same time that Goldblatt was capturing the long shadows of highveld winter, Mike Nicol’s poem ‘Returning’ in Staffrider (1984: 6) foregrounds the ‘brittle lawns’ of white suburbia:

Who returns to his winter suburb

walks familiar streets in the brown afternoons,

another itinerant passing wide of Alsatian and Doberman.

No-one looks up: children chase their fantasies

across brittle lawns. A year’s growth has thickened gardens

and spawned a new generation for the nannies on the

pavements.

Gardeners lurk behind hedges; a woman

shifts her chair to catch the moving sun.

The air carries intimations of despair:

a shower of ash lodging black in the curtains,

bodies massacred in room after room.6

The vitreousness of Nicol’s lawns is in stark contrast to the discursive softness of the lawns in the literary and technical archive. Apart from the brittle lawns in ‘Returning’ and Lungiswa Gqunta’s glassy installation Lawn 1 (see Plate 16), which I discuss in Chapter 4, the lawn is overwhelmingly and consistently described as ‘soft’, an ‘illustration of the beautiful’ (Jackson Downing 1853: 62; see also Johnson 1979: 154; Martin 1983: 467; Omole 2011; Stapf 1921: 88). The beauty, tranquillity and naturalness of the lawn are ideas that arrived in South Africa as part of the baggage of British empire. Even kikuyu, the lawn grass that has become naturalised in South Africa, was originally from the East Africa Protectorate and sent via Pretoria to Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London to be classified and propagated.

The ideal of the British lawn has been unexpectedly adaptable to the politics of the South African highveld, if not always to its climate. The flat, green lawn has been planted in locations as diverse as Pretoria’s Union Buildings (1913), the Voortrekker Monument (1949) and Freedom Park (2004); elite private high schools such as St Stithians, St Andrews and Roedean; the post-apartheid sculpture installation Long March to Freedom at Tshwane’s National Heritage Monument and the sculpture park at the Nirox Foundation at the Cradle of Humankind; and in Soweto, the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum has a dramatic axial line of lawn connecting the place where Pieterson was shot with the entrance to the museum. The lawn, here, is a peculiar vector from 16 June 1976 to the present.

The encounter between European landscape conventions and the South African environment, what Mary Louise Pratt calls the ‘contact zone’ (1991), is a territory in which scholars have sought to understand the problems of colonialism, dispossession, belonging, land and labour.

J. M. Coetzee set the terms for this debate with the publication of White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa (1988). His approach to the landscape was very much in line with the ‘dark side’ landscape critics from that period who argue that landscape is an ideological concept, a ‘way of seeing’ (Berger 1972), which ‘mystifies, renders opaque, distorts, hides, occludes reality’ (Wylie 2007: 69). Among other ‘dark side’ landscape critics, Raymond Williams (1975), John Barrell (1983) and Ann Bermingham (1986) argue that the landscape represents to certain people their imagined relationship with nature (Cosgrove 1984) and simultaneously hides the struggles, achievements and – importantly – the labour of the ‘inhabitants’ of that landscape (Daniels 1989). Coetzee extended and departed from these arguments in significant ways, particularly his concern with imperialism and racism.

In White Writing, Coetzee describes how South African landscape art and landscape from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century revolved around the question of ‘finding a language to fit Africa, a language that will be authentically African’ (1988: 7). He was concerned with the representational politics of ‘the land itself’ (10); work; visibility and the discourse of idleness; European schemas of thinking Africa, especially through the picturesque and the pastoral; and race, especially by marking and historicising whiteness. Zoë Wicomb and Jennifer Beningfield have pointed out how ‘white writing’ is ‘something incomplete, not fully adapted to its environment, something in transition’ (Wicomb 1998: 372), ‘plagued by doubts and insecurities … conflicts, ambiguities and silences’ (Beningfield 2006a: 18). These conflicts have animated a range of scholars, producing an eloquent and politically attuned body of literature (see Carruthers 2011; Darian-Smith, Gunner & Nuttall 1996; Foster 2008; Van Sittert 2003). Blank____Architecture, Apartheid and After, edited by Ivan Vladislavic ´ and Hilton Judin (1998), marks a strand of theorisation, present also in ‘Naturing the Nation’ (Comaroff & Comaroff 2001), concerned with the question of after: what possible shapes could a post-apartheid and postcolonial South Africa take?

However, apart from one brief study on the lawns of Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town (Mogren 2012), the only piece of research that offers a sustained, critical view of the South African lawn is David Bunn’s chapter ‘ “Our Wattled Cot”: Mercantile and Domestic Spaces in Thomas Pringle’s African Landscapes’ (1994). Published in the influential volume Landscape and Power, Bunn’s study of attitudes in the 1820s to landscape in the Cape Colony is important for two reasons. The first is its attention to the colonial lawn landscape and the second is how it works as part of the broader argument Mitchell advanced in Landscape and Power.

While Bunn critiques the naturalisation of settler subjectivity in ways that are familiar, showing how the eighteenth-century English landscape garden was exported to the periphery, he also departs in a fundamental way from the theorisation of the landscape as symbolic or representational. What he argues is that far from landscape being a symbolic expression of human intention or simply an aesthetic appreciation, landscape is, in fact, the (somewhat) independent instrument of cultural power.

Civilising grass

This book presents five introductory theses on the South African lawn, outlined below.

1.The lawn is political

The South African lawn has remained largely invisible in plain sight. Naturalised and treated as the product of common sense, the lawn appears to exist outside of politics and is commonly thought of as ‘neutral in struggles for power, which is tantamount to it being placed outside ideology’ (Fairclough 1989: 92). The ideological dimensions of the lawn are, however, perceptible and the discourse from which it emerges is evident in the archive. The lawn discourse governs, for instance, its colour, shape, texture, height, incline, level, orientation, relationship to buildings and so on. It also exerts control over practices, including those related to ownership and the creation, maintenance, usage, destruction, transfer and movement of the lawn. This discourse displays a strong tendency towards normative and value-based assessments of an individual lawn’s compliance or non-compliance with the ideal lawn. Lawns are seldom the star of the show, even when they are. (This is partly why they remained for so long inoculated against critical inquiry.) Lawns recede into the background and are favoured as backgrounds for the real drama of life. Foregrounding the lawn is a political act of denaturalisation, leading to a reversal of the normative figure-ground relationship.

2.The lawn is moving

Conceptually, aesthetically, materially and ecologically the South African lawn comes from somewhere else. Indeed, it is also on its way somewhere else. Colonialism and imperialism facilitate the lawn’s movement but also attempt to conceal that very movement. While colonial discourse relies on botanical transplantation and exchange, it also depends on the simultaneous impression of stasis to obscure its multidirectional and asymmetrical movements. The colonial landscape must not appear dynamic; it must seem stable, passive and immobile because timelessness and finishedness are fundamental requirements of the imperial landscape (see thesis 5). The lawn moves and grows rhizomatically: supposedly flat, even and soft, the lawn is not so much a surface as it is matter that connects, takes root and advances (down, up and outward). In this sense, the lawn is deep, not only because it tends to obscure what is beneath it but also because it is stubbornly knitted into and grounded in the earth. Following Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, I argue that the lawn is a weed and a ‘vegetable war machine’ (Marks 2010).

3.The lawn is work

Lawns require labour, time and money. In the past, sheep and other animals trimmed the lawn by grazing, and in a science fiction future, ‘mowbots’ (Greene 1970) may well keep the lawn. However, since the eighteenth century, humans have kept the lawn. Which humans – what gender, age, race and sexuality, for what pay or reward, on which day, at what time, in what conditions, with what equipment and inputs – is determined by the lawn discourse. In South Africa, which humans keep the lawn (and under what conditions) has everything to do with race and class. Anxiety about racial idleness and the injunction to conceal labour that does not support claims of land ownership underpin representations of the lawn (Coetzee 1988). Hence, the manner in which work done to the lawn is presented and represented, acknowledged and denied, remembered and ignored is very revealing about the power at work in the landscape. In addition to the work required to keep the lawn, the lawn itself is also at work. To focus on the inner workings of the lawn itself is to accord it a certain vitality and to acknowledge its power to produce certain effects in human and other bodies (Bennett 2010). The lawn’s work involves the complex process of producing subjects and perpetuating itself by extending rhizomatically over time and space – which is to say, colonising – without drawing too much attention to its fragility, its being-in-progress and its underlying aggression.

4.The lawn desires family

In a common-sense way, the lawn is strongly associated with children. For instance, it is quite typical for the literature to sincerely ask: but where would the children play if there was no lawn? Indeed, this question was especially vexing for white planners during the apartheid years, who worried about black children’s safety and cleanliness while at play. The lawn is historically understood to be a hygienic, safe, healthy, clean, modern surface, safe from ticks, snakes, traffic and dust, and exerting a ‘healthful’ influence (Dreher 1997; Mellon 2009). These sanitary discourses are focused on the bodies of children, the poor, the indigent, the disabled, the racially inferior and the sexually deviant in an attempt to reform their unhealthy and unproductive modes of place making. Public parks, sports fields and domestic lawns emphasise the desirability of family, wholesomeness and middle-class respectability. In opposition to this normalising drive, so-called anti-social queer theorists encourage resistance to being incorporated into productive heteropatriarchy. According to this argument, the child is understood to be the embodiment of ‘reproductive futurism’, which ought to be countered by a negative queer oppositionality (Edelman 2004). The embrace of queer negativity is in direct opposition to the lawn’s optimism and future orientation.

5.The lawn is a failure

The depressed, the hopeless, those without a stake are unlikely to make (good) lawns. Keeping a perfectly flat, even, green lawn is difficult and expensive work, easily compromised by extreme weather or low rainfall and so the successful lawn is often elusive, the cause of anxiety and insecurity. While the ideal lawn is understood to be fixed, permanent and durable, the lived lawn is really a mess: it is dying, flowering, rough, brown, bumpy, coarse, scratchy, dry, burnt, green, patchy, uneven and alive. It is an ideological function of the landscape medium to arrest complex processes and rhythms and to present them as stable. As a framing device, the lawn landscape was (and is) one of the tools at the disposal of the colonial and modern eye. And yet, at its heart, there is an internal contradiction because the lawn can, at best, only ever be a temporary victory. Essentially, the lawn is a landscape ‘without final outcome’ (Casid 2011: 103) and it is this open-endedness, this dynamic potential, that must be centred in a discussion of the colonial landscape. By queering the lawn we challenge the notion that it functions by way of injunction – No walking on the lawn! No blacks! No gays! – and that it is the binary opposite of the wilderness. The relation between the lawn and wildness is much more complicated; indeed, the lawn’s relation to human and non-human actors is much more complex. The lawn is strangely suited to misuse and reuse and is constantly and consistently failing even as it persists and even as it is unusually resistant to critique.

Structure of the book

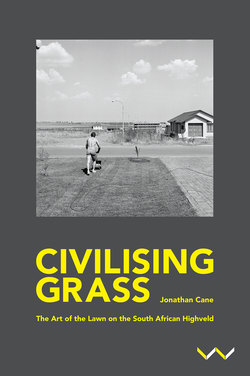

Civilising Grass consists of four chapters, which each deal with a particular aspect of lawns. These lawn moments, part of the larger lawn archive, are all located on the South African highveld, between the late nineteenth century and the present day. There is something discrete and somewhat unique about this geographic and historical selection. The discovery of gold, rapid industrialisation and crass commercialism, the Anglo-Boer War, the South African Union cemented in Pretoria, Nelson Mandela’s inauguration as president of South Africa on the Union Building lawns, all played out in a climatic zone that, compared to the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, is particularly unwelcoming to the arrival and imposition of the lawn. It seems to me that the highveld, particularly in winter, is perhaps the brownest landscape one could imagine – smog, veld, mine dumps and dust. And therefore, to even imagine (never mind actually plant and keep) a lawn in this place is to push the naturalness of the lawn trope to its most audacious limits.

However, I would argue that the findings of this book are relevant in general across South Africa and even in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya and Tanzania because of their Anglo-colonial similarities. That said, one would expect future research to flesh out differences. For instance, a study on KwaZulu-Natal would have to reckon with the influence of Brazilian modernist landscaping and the valorisation of tropicality, as Sally-Ann Murray (2006) has pointed out, and a study of the Cape would have to take into account the specifics of Cape colonial history.

The archive for Civilising Grass is composed from two groups of texts: those I call ‘scientific’, for lack of a better term, and those I call ‘artistic’. The distinction is not one that could hold up to any scrutiny; I could not possibly convince the reader that so-called scientific texts are not profoundly aesthetic, nor would I want to. To be deeply suspicious of any text that claims to be truth-telling is the inheritance of critical theory. And yet, in my archive, there is a coherent body of texts that claim to have something true to say about the lawn: This is how to mow it; this is how to plant from seed; that is too much water; these kinds of lawns are beautiful; those are unfashionable, uncivil, shameful and so on. These texts were written by experts – historians, administrators, scientists, botanists, teachers, gardeners, garden owners, garden writers, landscape architects and architects and they give shape to the discourses that govern the lawn. The writers often have uncomfortable things to say about ‘garden boys’, weeds, the poor and so on. They are overwhelmingly white – in fact, almost exclusively white – but many are women, and a couple are queer, too. They tend to write with little aesthetic or rhetorical finesse, but this lack of literary sensitivity can be read as signalling one of the ways a text of this kind makes a claim for facticity, strengthening its scientific pretensions and, possibly, its imagined lack of bias. What could be less political than advice on digging holes or choosing the right lawnmower?

If the first body of texts is characterised by its blindness to politics, the artistic texts are characterised by their blindness to the lawn. In these texts, the lawn is rarely the subject of the statement. And because the lawns I discuss are simply behind the sitter in the portrait, or in the foreground of the larger landscape or barely specified in architectural plans, they are difficult to track down and often unintended by the image-maker. This means locating lawns in artistic texts requires the collection of texts with the intuition that within the oeuvre of that author or artist there will be a lawn, somewhere. Those who have read Vladislavić, the biographer of Johannesburg, would expect to find a good many lawns in the geography of his writing, which they will. The same applies to the photographers Ernest Cole and David Goldblatt. But one would have had to have known to look there in the first place. The text collection was persistent and unsystematic – like cruising for sex in a park. The search term ‘lawn’ and permutations like queer lawn, black lawn, apartheid lawn, green lawn, post/colonial lawn, as well as translations like grasperk were put through digital databases and analogue searches. The first priority was South African and South African-focused texts, with an explicit intention to privilege texts by women, blacks and queers. I was willing to consider any medium: from poetry to pornography, online user comments to user-generated dictionaries, prophesies to painting, hate speech to children’s homework exercises, physical places to paper plans.

In selecting the lawns for analysis I especially searched for moments in which, for instance, a literary lawn clashes with a lived lawn or where a historical archive overlays a set of spatial practices. Here it was useful to think about Henri Lefebvre’s triadic conception of space, which suggests that far from being inert, neutral or pre-given, social space is a social product and every society produces its own space. The Production of Space shows that because of the ‘illusion of transparency’, space can appear ‘luminous’, ‘innocent’ and ‘free of traps or secret places’ (Lefebvre 1991: 27–28). Thus, it is possible and necessary to interpret social space as dialectically produced by representations of space, representational spaces and spatial practice (33).

Andy Merrifield explains that conceived space is dominant: expressed in numbers and systems of formalised signs, it functions in ‘objectified plans and paradigms’ (2006: 109). This kind of space finds its ‘objective expression’ in monuments and towers, in factories and office blocks, in the ‘bureaucratic and political authoritarianism immanent to a repressive space’ (Lefebvre 1991: 49). Spaces of representation (representational spaces) or ‘lived space’ are the ‘nonspecialist world of argot rather than jargon’, non-verbal symbols and signs (Merrifield 2006: 109), the ‘clandestine or underground side of social life’ (Lefebvre 1991: 33). Spatial practice or ‘perceived space’ includes the daily activity, which ‘secretes that society’s space’ (38), like the ‘pathways that spontaneously appear on a greensward as a result of walking patterns’ (Mitchell 2002: ix) and ‘routes and networks, patterns and interactions that connect places and people, images with reality, work with leisure’ (Merrifield 2006: 110). This is the space of daily routine (Lefebvre 1991: 38).

As Lefebvre argues, relations between the three moments of the perceived, the conceived and the lived are ‘never either simple or stable, nor are they “positive” in the sense in which this term might be opposed to “negative”, to indecipherable, the unsaid, the prohibited, or the unconscious’ (1991: 46). ‘Space,’ he argues, ‘may be said to embrace a multitude of intersections’ (33). The point should not be to dragoon the various spaces into domesticated intellectual submission. The goal of the present analysis is not to tame the profusion of unruly lawns.

Lefebvre’s theory underpins my approach to imagined spaces, maps, photographs of geographic spaces, intentionally and unintentionally unbuilt architectural proposals, empty spaces on the page (in literature, theory and plans) and empty spaces on the ground, patterns of lived space, the imagining, creation and use of play spaces, patterns of foot traffic, uses, misuses, reappropriations, deployment, rejection of spaces on paper, in person, by the body, against and with other bodies, both dead and alive. These assemblages complicate authoritative representation: they recognise the limitations of discursive analysis and attempt (within limits) to trace its silences. The goal is, however, not simply to examine the spaces from different angles or see different sides of the story. Rather, it is to examine how landscape and power are at work in producing human and non-human subjects in a process that is complex, open-ended, fraught and messy.

In Chapter 1, I work towards an operational definition of the lawn. By way of a discursive analysis of a number of key ‘scientific’ or truth-claiming texts from 1260 to the present, based on an extensive survey of English (as well as a limited collection of Latin, French and Afrikaans) gardening and landscape texts, the chapter identifies modes or themes. What the discourse analysis shows is a highly regulated terrain, with clear patterns governing what is and is not sayable and doable with respect to the lawn. It also shows a remarkable persistence over the long term – sometimes against all empirical evidence to the contrary. The lawn is understood in overwhelmingly positive terms, except for some picturesque writers of the eighteenth century and later anti-lawn campaigners. The overwhelming historical consensus is that the lawn is a good, clean, healthy and modern surface, worth aspiring to and worth the vast amounts of energy, effort and worry required to keep it as it should – indeed, must – be.

However hegemonic it may be, the lawn discourse is not totalising, and this chapter begins to identify many ambivalences, silences and contradictions. To trace a discourse is to be attuned to what was unsayable and undoable. By its nature, an archive excludes numerous subaltern voices. The small representation of working-class black female and black male voices is an expected limitation to encounter in a discursive study in a country with South Africa’s racial history. There is an acute need for primary empirical data on lived landscape from below, as it were, which would profoundly enrich our understanding of, and challenge our arguments about, the relationship between landscape and race. Apart from the absence of certain types of voices (a limitation of the methodology), the lawn (as a medium) itself functions in some instances as a kind of absence. As an ideal form, the lawn is often not fully accomplished, or indeed planted at all. Its normative and normalising frame can exercise its power even as a mental abstraction, a literary assumption or mode of seeing. Apart from these kinds of silences, certain internal contradictions unsettle the account of lawn landscape as fixed and permanent. One becomes aware of a kind of neurosis at the lawn’s limits and boundaries. Many of these fears and anxieties are barely whispers but are nascent of a challenge from the margins.

Chapter 2 engages with the fundamental quality of the lawn: that it must be made and kept. It requires material inputs, competencies, tools, time, labour. In the South African context, these conditions of possibility are constituted by and constituting of racial inequality. The chapter builds an extensive discursive analysis of the ‘garden boy’ and his place in the lawn landscape, arguing that the figure of the garden boy is important, under-studied and quintessentially southern African. He demonstrates the complex relationship between raced and gendered human and non-human life that characterises the colonial landscape. The garden boy’s subjection to his master/mistress, the stunting of his chronology, his abuse, his embodiment of white fear, his body as a machine, challenge the landscape’s attempted effacement of labour. While obviously made, the lawn still manages to hide or forget the labour that must continuously make it, the process of its emergence, the tenuous accomplishment that requires consistent and constant attention. The tendency to erase black labour is made all the more obvious by the instances where white garden work is recorded and monumentalised. The meaning of these different acts and the disparities in their modes of representation draw attention to the problems of race and respectability as they manifest in the domestic space. This chapter also attempts to examine the relationship between white women and the lawn. In what could be called a ‘Rhodesian’ discourse, women memoirists and novelists attempt to write a place for themselves in relation to black labour and the garden landscape.

Chapter 3 investigates a period of optimism, early- to mid-twentieth century, during which the lawn signified, often in entirely unstated and unconscious ways, one of the promises of modernity. The utopian discourses that energised much of the planning and urban design by white planners, just before and during apartheid, drew inspiration from and were part of international debates that were consummately amenable to the kind of racial social engineering desired in South Africa. This chapter attempts to historicise the landscape preferences of these technocrats and to connect their (so far unstudied) garden designs with the broader, established literature on apartheid spatiality. That these official ‘representations of space’ never materialised in the ways that were imagined and hoped for is to be expected. Thus, this chapter emphasises the multifarious ways in which ‘lived modernisms’ (Le Roux 2014) disrupt the sites under investigation, producing dynamic, unexpected and dangerous spaces. The chapter examines three sites: first, an audacious and unbuilt high-rise township for 20 000 ‘urban natives’, designed in 1939 by radical University of Witwatersrand students; second, the assemblage of spatial production in the black township of KwaThema, both historical and contemporary; and third, the landscape designs for the mining town of Welkom by Joane Pim and, as a contrapuntal reading, the landscape of the Welkom-Wes Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk by Roelof Uytenbogaardt. The case studies in this chapter provide a critique of the lawn’s teleological orientation towards progress and instead suggest, borrowing from Bruno Latour, that the lawn has never been modern (1991).

Drawing on anti-social queer theory, Chapter 4 explores the notion of failure as a potential site of freedom from heteropatriarchal capitalism and its teleology. Doing bad things to and with the lawn means including into the archive narratives of inappropriate, tacky, sleazy, perverted, incorrect lawn keeping and usage. The chapter presents three particular examples. The first is an analysis of Pennisetum clandestinum, better known as kikuyu grass, a remarkably mobile botanical actor that, after being ‘discovered’ in what was then the East Africa Protectorate, travelled first as a cutting in a milk-tin to Pretoria, then to London and then back to South Africa and other parts of the world. Officially categorised as an ‘excellent colonizer’ (Quattrocchi 2006: 1637), kikuyu’s vitality, mobility and aggressiveness offer a counterpoint to the dominant discourse that the lawn is peaceful, stable and immobile. The second example is Joubert Park in Johannesburg. The narrative of the park’s decline from Edwardian promenading ground to post-apartheid blight provides an opportunity to question the supposed failure of modernity. Contrary to what is often imagined, the photographic records of the park demonstrate the versatility and amenability of the lawn to alternative and incorrect uses. The third case study, the lawn in Marlene van Niekerk’s novel Triomf (1999), continues the elaboration of possible disruptions by and desecration of the landscape. Whereas the analysis of Joubert Park examines the threat of failing public space, the failing yard of the ‘poor white’ Benade family provides an opportunity to examine the possible repercussions of wrongful gardening for neighbourhood sociality. With the spectre of the 1994 elections and the end of apartheid hanging over the Benades, we witness obscene, funny, abject and violent effects in their garden. The landscape fails to contain the ambiguous claims of ownership and belonging to the land.