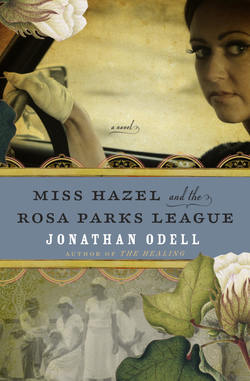

Читать книгу Miss Hazel and the Rosa Parks League - Jonathan Odell - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Thirteen

JESUS IN THE GRAVEYARD

Today up in Delphi at the white cemetery, Jesus weighed heavily on Johnny’s mind. He had listened carefully as Brother Dear talked to Jesus about keeping Davie safe and watched as they lowered his brother down into the hole. Johnny wanted to ask his mother how long Jesus was going to keep his brother down there, but she wouldn’t look at Johnny. She sat next to him stone-faced, smelling one minute of Gardenia Paradise and the other of the medicine she had been taking from half-pint bottles.

It seemed everybody around him was calling on Jesus except his mother, who grimaced every time somebody said his name. The biggest part of the town was there, sitting in rows and rows of straight-back funeral chairs, men sniffling and bashfully brushing their noses with the tops of their knuckles while offering their pocket handkerchiefs to their wives. Even his father wiped away tears as big as summer raindrops. Every now and then, from directly behind him, he heard the sobs of his aunt Onareen, the only one from Hazel’s family to attend.

“How long is Davie going to have to stay with Jesus, Momma?” Johnny finally whispered.

She acted as if she hadn’t heard him. Her dry stare was focused on Brother Dear, who shone brighter than sun on snow in his white suit. The preacher was now saying something about Jesus’s master plan and about never, never, never asking why.

Still staring at Brother Dear, Hazel shredded her tissue until there was nothing but a mound of white bits on the lap of her black silk dress. Floyd reached over and brushed her off and then rested his hand over hers, stilling them.

Returning from the funeral, Johnny asked his momma from the backseat how Davie was going to find his way back to the house. “Will Jesus set him loose at night? Oughten we come back in the car and get him so he don’t get lost?”

His mother swung her head around in the seat. “What are you going on about?” she shouted. “Davie ain’t coming home. Never! Do you understand me? Jesus don’t let nobody go once he gets aholt of them!”

Johnny sat stone still in the backseat. He was too startled to cry.

Floyd turned to Hazel. “Why are you yelling at the boy? Why are you yelling at all? Why ain’t you crying? Everybody else is. It ain’t right, you being dry-eyed at your own son’s funeral.”

Hazel looked accusingly at her husband. “Ain’t you the one always saying we can’t go back and change the past? That spilt milk ain’t worth crying over?”

After taking a deep breath and slowly letting it out, Floyd shifted to his low serious voice, the one he used when he felt he was getting to the nub of the matter. “I’ll tell you why you ain’t crying, Hazel. It’s because you’re stinking drunk. It ain’t cute no more. You get mean when you drink. Just like your daddy. And I’m sure everybody at the funeral smelt it.”

“I ain’t drunk, and don’t you talk about my daddy.” Hazel gritted her teeth. “And I’ll cry whenever somebody tells me why Davie is gone.” She shot Floyd a look that accused him of holding back the answer from her all along.

“Well. . .” Floyd said, not appearing so sure of himself. Finally he ventured, “Now Jesus tells us we got to—”

Hazel flew hot again. “I done heard enough about what Jesus tells us! Jesus and his many mansions. Jesus and his big ol’ everlasting arms. If His arms is so big and strong, how come they didn’t catch Davie? Tell me that!”

Floyd didn’t offer an answer. When Davie had died, Floyd and his big ol’ arms had been there, too. Floyd had been working on the lawn mower when Davie decided he wanted to play “Catch me” from the porch. Certain as always that his daddy was watching, Davie stepped to the rail edge and stretched out his arms.

Only Johnny had been watching. It was he who had heard his brother’s voice call out “Catch me,” sounding more like the chirp of a bird, and only Johnny who saw Davie drop off the man-tall porch. It wasn’t until his father heard the soft thud on the grass and then something resembling the sound of a twig snapping that he glanced up from the mower to see Davie lying in front of him motionless, his arms akimbo, neck broken, facing Floyd with only the slightest look of surprise.

In the autumn that followed the funeral, Hazel’s unshed tears hung dark and heavy on the family’s horizon like an approaching Delta storm. The drinking continued. Hazel said if she couldn’t drink, she would surely suffocate. She said, “Drinking is like breaking open a window to yell out of.”

Floyd said he was trying to understand, but all he thought her drinking did was make her mad. He said every time he looked at her, all he saw in her eyes was a fight ready to happen, and he couldn’t afford being around somebody that negative all the time. Not with everything they had riding on his positive attitude. Finally, he moved into a separate bedroom.

They left Davie’s bed and toys and clothes untouched, strengthening Johnny’s belief that his brother was coming back. Several times a week he awoke to his father silhouetted in the doorway, looking toward Davie’s bed for minutes at a time. One night, after a particularly loud fight between his parents, Floyd came to the doorway and stood there as usual, staring. This time, Johnny thought he heard a sniffling sound.

“Hey, Big Monkey,” Johnny called out to him.

“Hey, Little Monkey,” his father whispered, in a way that made Johnny’s heart hurt.

“He’s not back yet, Daddy,” he said, trying to comfort him. “I’ll holler at you when he gets home.”

Later, after his father had gone to bed, Johnny woke to the touch of a hand running through his hair. As his mother knelt by his bedside, smelling strongly of medicine, she whispered the oddest question in his ear.

“Who do you love the most? Me or your daddy?”

Certain of the answer she wanted, he said, “You, Momma.”

She bent over and kissed him on his forehead and said before leaving, “Don’t tell your daddy. You’re on my side. Do you hear?”

His mother’s question tore the world in two for Johnny. It was like the day he had seen the setting sun and the rising moon in the sky at the same time, opposite each other. Until that moment, he believed they were the same entity, the silver moon being the soft evening face of the hot, laboring sun. Yet when his mother asked him that question and made him choose between his parents, Johnny grasped how separate his parents really were. They traveled in their own orbits. And most terrifying of all, there could be one without the other.