Читать книгу Dream. Believe. Achieve. My Autobiography - Jonathan Rea - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1 Sixty Saturday, 9 June 2018, Automotodrom Brno, Czech Republic

ОглавлениеThe stress levels are at maximum now.

At the very last moment, just as I roll to a stop, I find neutral. I give Uri a gentle nod, because he’s always as stressed as I am about me finding it. I turn back to the start lights and do a couple of nervous twitches with my head, something that’s developed over the last few years. All the other riders are in position. The start marshal walks off, pointing his red flag towards the lights. We wait. Those lights will come on for anything between two and five seconds. As soon as they go out, it’s a start. I engage first gear and activate launch control.

The lights come on, I twist the throttle. The decibel level soars as the other riders do the same. One … two … three … four …

It’s race day.

This morning I qualified second fastest in the Superpole session – the middle of the front row of the grid. The whole post-Superpole parc fermé thing, photographs and interviews, is dragging on. It’s less than two hours from the lights going out for the 1pm race. I’m thinking I need some food and quiet time.

What I am definitely not thinking is this: I’m not thinking I could be breaking a record today. Sixty doesn’t enter my mind.

I run back to my race truck office where my personal assistant Kevin Havenhand has picked up some grilled chicken and broccoli. I’ve not eaten since breakfast and I need to get this down now so I’m not bloated for the race. I scoff it while getting changed and watching the qualifying sessions for one of the support classes, Supersport 300, but I don’t eat much – just enough so I don’t feel hungry later. I stay in the truck while the physio checks my ankle, which has been hurting the last couple of days. My riding coach, Fabien Foret, is running through final details about the race and my plan of attack. He leaves and switches off the lights and I roll out a mat on the floor and rest my head on a team jacket. I’m out like a light.

The alarm goes off a quarter of an hour later, around ten past twelve, which gives me another 15 minutes to get ready. Kev has got a fresh, clean inner suit ready and all my riding gear is lined up in neat rows, just how I like it. I hop on the scales – a normal 71.3kg. Albert’s back in to log my weight and apply some Kinesio therapeutic tape to my arms. I had some arm-pump problems at the previous round – ‘carpal tunnel syndrome’ caused by heavy braking and the constant pressure and vibration. It can cause numbness and tingling, and it’s bloody painful; but that was mostly down to the nature of the Donington Park circuit and I’ve had no problems here at Brno, so this is just a precaution. As soon as that’s done, I finish climbing into my leathers and me, Kev and Fab are marching out of the office like the Three Musketeers.

We know that we have the pace to win here – I’ve been fastest in all the longer runs we’ve done in practice – so strangely this is one of the tougher weekends mentally. I’m starting from the front row and I know I’m faster than everyone else, so the only person who can mess it up is me.

Fab reminds me of that and talks about the initial plan for the race: relax, get into a rhythm and see how the first few laps pan out. If I’m in front, I’ll do a five-lap attack, put my head down, try to build a lead and manage the race from there.

What is it they say about battle plans? None of them survives first contact with the enemy …

I’ve been nervous since I started changing. I’ve got that familiar feeling of knotted tension in my stomach as adrenalin begins to flow around my body and it subconsciously prepares for fight or flight (or maybe both).

One minute, I’m focusing on my getaway, needing it to be clean and fast. The next, I’m wondering who is going to be challenging me this afternoon. It could be Marco Melandri, lining up to my right on the front row. He’s shown some pace. Or it could my team-mate Tom Sykes, on the other side in pole position.

Mostly, I’m starting to focus on winning. Only winning. It’s the reason I’m here, it’s the thing I’m paid to do.

It’s 12.25pm and I’m on my chair in the garage, waiting for the pit-lane to open at 12.40, running through a few last-minute details with my crew chief, Pere Riba, who is confirming which tyres we’re using and whether he’s made any final changes to the bike. We’re rolling into the race with the exact same bike we had in Superpole. I give my mechanics a tiny nod and they whip off the tyre warmers – little electric blankets that keep the tyres ready at around 90°C.

The Kawasaki ZX-10R is fired up and we’re out on the sighting lap, once around the circuit and back to form up on the grid. I take in the crowd, especially in the stadium section – a series of four corners with a massive grassy bank off to the right, a great place to watch. There was quite a crowd during this morning’s sessions, already on the beer and enjoying the Czech hospitality, so they’re pretty noisy by now. I see quite a few Northern Ireland flags as well – hello, boys.

I roll up to the front row of the grid where the crew take off my gloves and helmet. I point out to Pere that the brakes are binding a little but everything else is OK. The brakes thing is nothing major, and the guys are on it straight away, but I’m particularly sensitive to it today. Must be the adrenalin.

The nerves are really kicking in. They’ve been building since I was changing, and they make my breathing a little shorter and my mouth quite dry. I’m hydrating often, without thinking; it’s instinctive now.

I’m aware of a Monster Energy grid girl on my left and a Pirelli ‘Best Lap’ girl on the right. I’ve got the highest number of fastest laps this season and she’s there for a PR opportunity with the official tyre supplier in front of the TV cameras on the grid. But my nerves are playing hell with my bladder and I’m busting for a piss, so I ruin the TV moment by running off the grid towards a toilet at the bottom of the race control tower.

In previous years, if I was caught short I’d have a piss at the side of the grid. The organisers didn’t like it though – too close to sponsor banners – and if I do it again I’ll be fined €5,000.

When I get back, everyone’s quiet and focused – very few words from the mechanics or me. Two TV crews come over for an interview. The first is from Austria, simple questions about the race; the second is British Eurosport and their reporter Charlie Hiscott, who starts asking when I’m going to decide who I’ll ride for next season.

He asks if I have a plan, so I tell him the only plan I’m thinking about right now is getting on with this race.

The five-minute board goes up and, because I always like to have my helmet and gloves on before the three-minute board, I take off my cap and sunglasses and hand them to Kev, who’s standing just to my right. The air temperature is around 26°C, so I rub my face and hands with a cool damp towel. I pull on my Arai, tighten the D-ring strap and bring down the visor about halfway, then push my hands into my Alpinestars gloves. As the three-minute board goes up, most of the team give me a pat, or a thumbs-up, and head off the grid, leaving just me and my two mechanics – Uri, who looks after the tyre warmer and bike stand at the front, and Arturo, who takes care of the rear. Uri stands there beside me and gently rubs his hand up and down the outside of my thigh.

He and I are quite connected, almost subconsciously. Maybe that’s why we never talk about the fact that he stands there and rubs my leg during those last few minutes on the grid. But because I’m so nervous it’s strangely comforting, knowing someone’s there with me as I’m just staring at the dashboard, trying to visualise the perfect start. With about one minute and thirty seconds to go, Uri flicks the ignition on and starts the bike and, as the final one-minute board goes up, the tyre warmers come off, the bike is taken off its stands and I get a homie-style hand shake from Uri.

‘Vamos,’ he says. ‘Let’s go.’ Arturo does the same, but with no words, and off they both go. It’s me and the bike, and 18 laps of Brno.

Then we get a green flag to start the warm-up lap.

I put my left foot under the gear-shift lever and click it up to select first gear (the gearbox has a race shift pattern, the opposite to a road bike).

I accelerate away from the start line and push down on the lever to select second, again for third.

Then we’re braking for the first corner and I’m nudging the lever up to go back down a gear.

I always do a fast warm-up lap and get back to the grid quickly to give myself a few extra seconds. As I come out of Brno’s final corner, I accelerate hard in second gear and then start giving the lever the gentlest nudge upwards as I roll towards my grid position, struggling to find neutral.

I’ve suffered from false neutrals in the past – when the gearbox finds neutral instead of engaging the gear you want – so my team has deliberately made it difficult to find.

I need to find it for the start of a race because, when I click into first gear immediately after neutral, the bike’s electronic launch control system is automatically engaged.

I hold the throttle wide-open, and it sets the rpm at the right level in the torque range to maximise acceleration. I feed out the clutch to launch the bike, then I have to adjust the throttle slightly to try to keep the engine in the same rpm range. It’s a fine art, but at the end of virtually every session I do a practice start and it’s something I’ve mastered over the years.

At the same time, there’s another part of the launch control that prevents the front wheel going up in the air as I pull away from the line. But the possibility of not finding neutral before the start always makes me even more anxious.

Then I find it, and I give Uri that nod and the starting lights go on.

One … two … three … four …

The lights take four seconds to go out and we’re away, eyes focused on the turn-in point for the first corner, about 450m down the track.

My start is perfect, and, with a power-to-weight ratio not far off that of an F1 car, the acceleration is amazing.

I see nothing but the track ahead, no other bikes in my peripheral vision, although I know they’re there.

I hit my braking marker and sit up from behind the bubble of the screen as my right index finger squeezes the brake lever.

My head and chest are slammed by the force of the wind that’s trying to blow me off the back of the bike, which is itself pitching forward under the brakes.

I don’t know how much force is going through my arms and wrists – in both directions as I’m hanging on to the handlebars – but it feels like a lot.

I move my right butt cheek off the seat and prepare to tip into the right-hander, leaning the bike over to counter the centrifugal forces that want to send both it and me in the opposite direction.

I lead into the long 180° first corner and extend my right knee outwards until the plastic knee-slider is skimming the kerb, telling me how far the bike is leant over.

This is when the tyres do their thing, the sticky, treadless rubber preventing the bike from sliding out from underneath me through a contact patch on the tarmac about the size of a credit card.

Coming out of the corner, I pick the bike up, shift myself back into a central position and put my head back down behind the screen. I’m accelerating hard towards the little left kink that is turn two and then off to turns three and four, a tight left followed quickly by a slightly more open right, like a big, fast chicane.

The nerves have disappeared and I’m focusing on braking markers, turn-in points, apexes. My head’s down, I take no risks and make no mistakes and, before I know it, I’m out of the last corner and looking for my pit-board – a summary of key information held out for me by my team, which I can glance at as I go back down the start-finish straight. I want to see the gap, in seconds, over the rider immediately behind me.

I catch a glimpse as I scream past. It’s +0.0.

No way. That can’t be! I’ve made a perfect start and done a great first lap. I’ve been so quick all weekend – I must have some kind of small margin at least.

One lap later, the gap is reading +1.5. That’s more like it. I’m away, determined to start building a lead and control the race from the front.

Then I see red flags – the race has been stopped.

A bike has crashed into a strip of air fencing, puncturing the inflatable barrier. I see it as I ride past turn five and I know we’re going to have to wait for a replacement unit, which is going to take a few minutes. I roll back up the pit-lane and into the garage where Pere is saying everything’s great, we’re in control. I asked him why the gap was +0.0 on the first lap and he says it wasn’t, it was +0.9. I must have been looking at my team-mate’s pit-board and not my own. It’s the first time in the whole weekend all the pit-boards have been held out at the same time, so I need to concentrate on finding mine. I ask Kev for another visor with three tear-offs because there are a lot of bugs out there. I hate having bugs on my visor – I’d be useless at the TT.

Now we have to go out and do a quick-start procedure – a sighting lap, one mechanic on the grid to show me my start position, no tyre warmers. Another quick warm-up lap and more stress trying to find neutral, rolling up for the second start. Another routine nod to Uri and we’re waiting for the lights again. I’ve got the bike held in launch control mode, but now there’s another problem – the lights just kind of flicker and then go off again. Yellow flags everywhere. A board is held out of the starter’s position above the track: Start Delayed. It’s the right call from a safety point-of-view, but this race is fucked up.

I switch off the engine straight away because it’s over-heating, and I wait for the mechanics to swarm back out to the grid and put the tyre warmers back on. I take another visor from Kev, because I always use a tear-off on the warm-up lap. Race control puts out a sign saying the race has been reduced to 16 laps. Off we go again – another warm-up lap, another fumble for neutral, but this time I’m worried I might have fried the clutch on the aborted start. Normally, my crew changes the clutch after one practice start. We’re about to do our third in this race.

I’m back in my grid position, the start marshal is walking off and the lights come on again, without any problem, and they go out after a similar wait. I get another good start, focus again on my braking marker and turn in for the first corner, only this time I go in pretty equal with my team-mate Tom, who’s starting from pole position. He is virtually on top of me as he tips in, causing me to sit up a bit.

So, this is first contact with the enemy – and that battle plan agreed with Fab duly goes out the window.

Fuck this. Instead of waiting for five laps for the race to settle down, I’m taking control.

I take a slightly wider line than Tom through turn one, pulling the bike back to a really late apex so I can square off the end of the corner and get on the gas hard. I cut across the kerb on the inside of turn two and rocket past Tom so fast on the drag down to turn three.

Don’t out-brake yourself. Just hit the apex, pick the bike up quickly for turn four and block him in case he tries to get back round. I’m still in front as I charge down to turn five. Now I can manage the race.

I complete a great first lap, check the pit-board – the right one this time – and it reads +0.4 and the next time around it’s +1.1, after a 1m 59.535s lap. It turns out to be the fastest lap of the race and perhaps promises another Pirelli Best Lap moment of TV gold (as long as I don’t need another piss).

The gap continues to grow, but on lap four a bug splats right in the middle of my visor, directly in my field of vision. I’m in a dilemma: if I use a tear-off now, I’ll only have one left to last the rest of the race. I decide to push on, squinting around what’s left of the bug.

Arturo’s on my pit-board and he’s almost telepathic in knowing what information I need to see. The gap has continued to build, but now it’s Marco Melandri directly behind me – he must have passed Tom, unless Tom’s had a problem. I start to wonder if Melandri’s found some extra speed for the race, but Arturo is instinctively putting the Italian’s lap times below his name on my board as well – it’s reading +3.5, Melandri, 00.5 (his lap time of 2m 00.5s) and I can see from my dash that I’ve just done a 2m 00.3s. If I can keep doing that, two- or three-tenths each lap faster than the guy behind me, I can keep pulling away. He’s not going to catch me.

This is my mindset – every corner, every sector, every lap – for the rest of the race: check the pit-board and keep going that little bit quicker than Melandri.

I’ve done so many laps of Brno over the weekend, plus a test here a few weeks ago. I know exactly where to brake, where to turn in, how each corner should feel – it’s metronomic, instinctive. But it’s the hottest part of the weekend and the front tyre is starting to degrade. As I roll gently off the gas and go into corners with some lean angle, the bars start to rock a little in my hands because the tyre is moving underneath me.

The rubber is so hot that the molecules in the tyre’s construction are moving around inside the compound. I’m aware of it as I go through the stadium section, turns five and six especially.

The front tyre is tapping me on the shoulder and saying, ‘Hey, this is the limit for today.’

If Melandri doesn’t have this problem, if his bike is set up a little differently and putting less stress on the tyre, he’s going to catch me. But I see the pit-board again, and the gap is still increasing: +3.8, +4.1, +4.5, +4.7. Just keep doing what you’re doing, don’t make any mistakes. Suddenly, my pit-board is reading L1, the final lap, I’m +5.1, and only now do I start thinking about actually winning the race.

I’m powering up the hill towards the end of the lap for the last time and the bike wheelies a little before the final chicane, turns 13 and 14.

As I exit the last corner, I catch another wheelie perfectly and cross the line on the back wheel, standing up, nodding to my crew who are crawling all over the pit-wall fence.

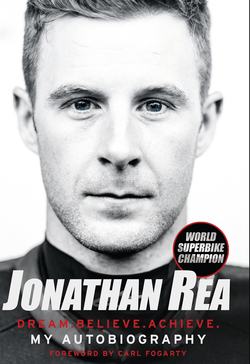

They’re holding a board that displays a specially-designed logo – 60 victories, Recordman – and that mantra.

Dream. Believe. Achieve.

I hardly take any of it in, because I’m still pulling this insane wheelie that feels so good I carry it the entire length of the straight, almost down to turn one. Then, as I land the front wheel, the pit-board message hits me.

It’s my 60th World Superbike victory.

Not bad for a country lad built for motocross.

I roll round turn one, taking it in.

Oh my God! I’ve got the most Superbike race wins in history. More victories than any other rider since the championship began; one more than the Superbike legend that is Carl Fogarty, whose record stood for almost 20 years. The team’s marketing manager, Biel Roda, spoke to me about this moment earlier this morning but I barely took it in. ‘Hey,’ he said, ‘if something happens today, we’ll be at turn 11, OK?’ I knew what he meant and I just replied ‘Cool, OK.’

I do the slow-down lap pretty much on my own, because I had such a big lead at the end of the race. I get to turn 11 quite quickly where Biel is waiting with Ruben Coca, one of the technical guys, and Silvia Sanchez, the team co-ordinator and life and soul of the entire organisation.

It’s so cool to see them all there, and they’ve got a special T-shirt and flag prepared for me. As I pull on the T-shirt, I start to realise I’ve made some history.

How did I get here? It’s been one hell of a ride …