Читать книгу Thanks, Johnners: An Affectionate Tribute to a Broadcasting Legend - Jonathan Agnew, Jonathan Agnew - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter One

The Guest Speaker

I can remember the first time I heard Test Match Special. I was aged eight or nine, and enjoying another idyllic summer of outdoor life on our farm in Lincolnshire when I became aware of my father carrying a radio around with him. It was not much of a radio, certainly not by the standards of today’s sleek, modern digital models, but was what we would have called a transistor. It was brown in colour and, typical of a farmer’s radio, was somewhat beaten up and splattered with paint. The aerial was always fully extended. Dad would often laugh out loud as he carried it about, the programme echoing loudly around the barns and grain silo as he stored the freshly harvested wheat and barley. It is the perfect summer combination, the smell of the grain and the sound of the cricket, and whenever I think of it the sun always seems to be shining, although that is probably stretching things a bit. When he had finished work for the day, we would play cricket together in the garden, Dad teaching me with tireless patience the basic bowling action. He so wanted me to become an off-spinner like him.

Soon the unmistakable voices became very familiar: Arlott, Johnston, Mosey and the others who with their own different and individual styles helped the summers pass all too quickly with their powerful descriptions and friendly company. The programme sparked an interest in me, in the same way it has in so many tens of thousands of children down the years, igniting a passion that lasts a lifetime. Whether it be playing the game, scoring, watching, umpiring or simply handing down our love of cricket to the next generation, listening to Test Match Special is how most of us got started.

Thanks to that programme, and Brian Johnston’s commentary in particular, I have always associated cricket with fun, banter and friendship. As a boy, if there was cricket being played, I would be following it either on the television or on the radio. Brian was always incredibly cheerful, and it was impossible not to listen with a smile – even if England’s score was really terrible and Geoffrey Boycott had just run somebody out again. Dad’s enjoyment of the humour within the cricket commentary was infectious, and made me appreciate everything that sets Test Match Special apart from other radio sports programmes.

I became rather obsessed with the game, even to the point of blacking out the windows of our sitting room and watching entire Test matches on the television. Until I was ten Brian commentated more on the TV than on the radio, but in 1970, when he was dumped by BBC television with no proper explanation, he moved to radio’s Test Match Special full time. So I joined the legions of cricket nuts who watch the television with the sound turned down and listen to the radio commentary instead. I actually lived the hours of play, with Mum appearing a little wearily with a plate of sandwiches at lunchtime, and some cake at tea. I would not miss a single ball on that black-and-white television, and while my parents recognised how much of a passion I was developing for cricket, I think they felt I needed to get out more. I remember a cousin of mine, Edward, being invited to stay during a Test match. I was furious, and felt this was clearly a plot to get me out of the house and into the fresh air. But Edward sat quietly beside me in the dark for the next five days. By the end, I think he was even starting to like it a little.

At the end of the day’s play it was out into the garden, where I would bowl at a wall for hours on end, trying to repeat what I had seen, and imitating the players, whose styles and mannerisms were etched in my mind. I developed quite a reasonable impersonation of the England captain Ray Illingworth, even down to the tongue sticking out when he bowled one of his off-spinners, and I loved John Snow’s brooding aggression and moodiness. How did Snow bowl so fast from such an ambling run-up? Little could I have imagined that Illingworth would become my first county captain, and that when I moved to journalism Snow would be my travel agent. Then there was the captivating flight and guile of Bishen Bedi, wearing his brightly coloured turbans, and the trundling, almost apologetic run-up of India’s opening bowler, Abid Ali. And Pakistan’s fast bowler Asif Masood, who seemed to start his approach to the wicket by running backwards, and who Brian Johnston famously – and, knowing his penchant for word games and his eye for mischief, almost certainly deliberately – once announced as ‘Massive Arsehood’.

I loved the metronomic accuracy of Derek Underwood, who was utterly lethal bowling on the uncovered pitches of that time, and still have a vivid memory of the moment he bowled out Australia in 1968 – helped, I am sure, by the fact that Johnners was the commentator when the final wicket fell. It was an extraordinary last day of the final Test at The Oval, where a big crowd had gathered in the hope of seeing England secure the win they needed to square the series. A downpour in the early afternoon seemed to put paid to the game, but when it stopped the England captain, Colin Cowdrey, appeared on the field and encouraged the spectators to arm themselves with whatever they could find – towels, mops, blankets and even handkerchiefs – and get to work mopping up the vast puddles of water. On they all came, to the absolute dismay, I imagine, of the Australians, and in contravention of just about every modern-day ‘health and safety’ regulation in existence. Before long, with sawdust scattered everywhere, ‘Deadly Derek’ was in his element. With only three minutes of the Test left, and with all ten England fielders crouching around the bat, he snared the final wicket: the opener John Inverarity, who had been resisting stubbornly from the start of Australia’s innings. Inverarity was facing what was almost certainly the penultimate over, with the number 11, John Gleeson, at the non-striker’s end.

‘He’s out!’ shouted Johnners at the top of his voice. ‘He’s out LBW, and England have won!’

This was my first memory of the great drama and tension that cricket can conjure up, and it came as a result of watching heroes and epic contests on television. This is the reason for my dis appointment that most of today’s children do not have the same opportunity. How can you fall passionately in love with a sport you cannot see?

At Taverham Hall, the prep school just outside Norwich that I attended as a boarder from the age of eight, there was a small television in the room in which you sat while waiting to see matron in the adjoining sick bay. She was a big one for dispensing, twice per day for upset tummies, kaolin and morphine, which tasted utterly disgusting, and then, as a general pick-me-up, some black, sticky, treacly stuff which was equally foul. Despite that, my best pal, Christopher Dockerty, and I would rotate various bogus ailments on a daily basis in order to get a brief look at the cricket on her telly – even just a glimpse of the score was enough. Matron never twigged that Christopher and I were only ever under the weather during a Test match. Incidentally, Chris was a brilliant mimic who could bowl with a perfect imitation of Max Walker’s action while commentating in a more than passable John Arlott. He was also the most desperately homesick little boy in the school. His later life would take an unexpected and ultimately tragic turn. As Major Christopher Dockerty he became one of the most senior and respected counter-terrorism experts in the British Army. Posted to Northern Ireland, he was a passenger on the RAF Chinook helicopter that crashed on the Mull of Kintyre in June 1994, killing all twenty-nine people on board.

My first cricket coach at school was a woman. Eileen Ryder was married to an English teacher, Rowland Ryder, whose father had been the Secretary of Warwickshire County Cricket Club in 1902, when Edgbaston staged its first Test match. The R.V. Ryder Stand, which stood to the right of the pavilion before the recent redevelopments, and where I used to interview the England captain before every Test match there, was named after him. Mrs Ryder was patient and kindly, and along with my father was the person who really taught me how to bowl at a tender age. Like him, she reinforced the image I already had of cricket as a happy and friendly occupation.

A couple of years later we had our first professional coach when Ken Taylor, a former Yorkshire and England batsman, professional footballer and wonderful artist, moved to Norfolk. A gentle and quiet man, he might well have played more than his three Tests had he been more pushy and enjoyed more luck. It has been said that he was an exceptional straight driver because of the narrowness of the ginnells – those little passageways that run between the terraced houses of northern England – in which he batted as a child. I suspect some of the ginnells might even have been cobbled, which would have made survival seriously hard work.

The privileged boys of Taverham Hall, in their caps and blazers of bright blue with yellow trim, must have been quite an eye-opener for Ken. I saw him for the first time in the best part of forty years when Yorkshire CCC held a reunion for its players in 2009, and one of his paintings was auctioned to raise money for the club. It was the most lifelike image one could imagine of Geoffrey Boycott playing an immaculate cover drive. I regret not buying it now, given my close connections to both men. In any case, I managed to encourage Ken onto Test Match Special, and memories of hours spent in the nets with him at Taverham came flooding back.

A trip to London in those days was considered by my dad to be quite an outing, but he booked tickets for the two of us to watch Lancashire play Kent in the 1971 Gillette Cup final at Lord’s. He was still reeling from a disastrous attempt to find Heathrow airport by car at the start of our recent family summer holiday. Utterly lost and desperate, he flagged down a passer-by who kindly offered to take us there, but instead directed us to his house somewhere in London, whereupon he jumped out, leaving us stranded. We opted for the train this time.

The whole occasion had a profound impact on me. The smell and sound of Lord’s was captivating, and it was a good match. I was thrilled by the sight of Peter Lever, the Lancashire fast bowler, tearing in from the Nursery end from what seemed to me an impossibly long run-up. Sitting side-on to the pitch in the old Grandstand, I had never seen a ball travel so fast, and Peter immediately became my childhood hero. The Lancashire captain Jack Bond took a brilliant catch in the covers, and David ‘Bumble’ Lloyd scored 38; these ex-players are all now friends of mine. Dad took his radio, but with an earpiece so I could listen and gaze up at the radio commentary box high to my right in the nearest turret of the Pavilion. All the usual suspects were on duty, and it is surprising to remember now that Brian Johnston, then aged fifty-nine, was only one year away from compulsory retirement as the first BBC cricket correspondent. I suppose I might have wished that one day I would also be commentating from that box, with its wonderful view of the ground. Twenty years later, I would be doing just that.

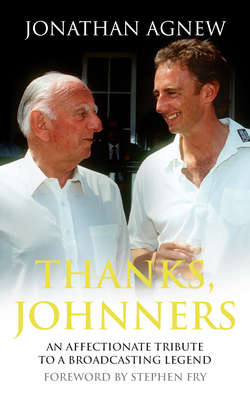

I moved on to Uppingham School in Rutland in 1973, and one year there was great excitement amongst the boys because Brian Johnston was coming to give a talk. These events usually took place in one of the smaller assembly rooms, which were commonly used for concerts and such things, or in the school theatre. Guest speakers did not normally arouse much excitement among the boys at Uppingham, and those who did come were usually untidily bearded professors and the like. But this was different, and any boys who were not aware of who Brian was, would have been told firmly by their fathers to attend. In the end, such was the demand that Brian addressed us in the vast main hall, which spectacularly dominates the central block of the school’s buildings and which could seat all the pupils and staff – a total of close to nine hundred people. It was almost full. I remember Johnners wearing a grey suit, and standing very tall at a lectern in the middle of the enormous stage. If he had any notes, they can have been little more than a few scribbled jottings. He certainly did not read from a script.

I was sitting about a third of the way down the room, and assumed that Brian would talk purely about cricket, but this was the moment I started to realise that there was more to his life than just cricket commentary. Typically, he was more interested in getting laughs during his well-honed speech than he was in telling us about the more interesting and intimate aspects of his life. That would also be the case when we worked together, because for Johnners everything simply had to be rollicking good fun; almost excessively so. Significant and poignant events in his life, such as the unimaginable horror of watching his father drown off a Cornish beach at the age of ten, or being awarded the Military Cross in the Second World War for recovering casualties under enemy fire, were absolutely never mentioned. Is it possible that his almost overpowering bonhomie, which some people could actually find intimidating rather than welcoming, had been a means of coping with the impact of his father’s sudden and tragic death when Brian was a youngster?

The annual summer trip to Bude was a Johnston family tradition that had been started by Brian’s grandmother, and even extended to their renting the same house every year. The Johnstons were a large family with a very comfortable background as landowners and coffee merchants. Reginald Johnston, Brian’s grandfather, was Governor of the Bank of England between 1909 and 1911, and his father, Charles, had been awarded both the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross while serving as a Lieutenant Colonel on the Western Front in the First World War. At the end of the war he returned to the family coffee business, which required him to work long hours in London. As a result Brian, the youngest of four children, saw little of his father, and consequently they did not enjoy a close relationship. Brian’s early childhood was, nonetheless, a happy time, spent on a large farm in Hertfordshire, and with the war over, he and his family had every reason to feel optimistic about the future.

All this was destroyed in the summer of 1922, when the Johnston clan, together with some family friends who were holidaying with them, settled down for a day on the beach at Widemouth Sands in north Cornwall. Ironically, Brian’s father had been due to return to London that morning, but had decided to stay on. At low tide, they all went for a swim. The official version of events is that Brian’s sister Anne was taken out to sea by the notoriously strong current and, seeing that she was in trouble, the Colonel and his cousin, Walter Eyres, swam out to rescue her.

Anne was brought to safety by Eyres, but Brian’s father, who was not a strong swimmer, was clearly struggling as he battled against the tide to reach the shore. A rope was found, and one end was held by the group on the beach while another member of the party, Marcus Scully, took the other end, dived into the water and desperately swam out in an attempt to save Colonel Johnston. But the rope was too short. Scully could not reach the Colonel, who was swept out to sea and drowned at the age of forty-four.

The tragedy was clearly a devastating moment in Brian’s life, and neither he nor his brothers and sister could ever bear to talk about it. To the ten-year-old Brian, his father, a highly decorated army officer, must have been an absolute hero. How can the young boy have felt as he stood helplessly on the shore and watched his father drifting slowly out to sea? A few weeks after the Colonel’s death, his own father – Brian’s grandfather – died from shock.

The whole dreadful saga was made even more complicated by an extraordinary turn of events. Only a year later, Brian’s mother, Pleasance, remarried. Her second husband was none other than Marcus Scully, whose rescue attempt had failed to save Brian’s father. There had been some gossip about the pair having been on more than friendly terms before the Colonel perished. However, it seems more likely that Scully, who was the Colonel’s best friend, suggested that he take on the family in what appeared, to the children at least, to be a marriage of convenience. In the event, it did not last long, and when they divorced Brian’s mother reverted to being called Mrs Johnston.

Interestingly, Brian’s recollection of his father’s death in his autobiography differs from this, the official account, in one crucial respect. As Brian told it, it was Scully who found himself in trouble, not Brian’s sister Anne, and it was a heroic attempt to rescue Scully by the Colonel that cost him his life. This version of events appears to have been a typically charitable act by Brian in order not to distress his sister, who, the family privately agreed, was at fault for ignoring warnings not to swim too far away from the beach, and got into difficulties. Brian could not bring himself to blame her for their father’s death in print, and so concocted a different story for his book.

Brian’s education had started at home with a series of governesses, then at the age of eight he was sent away to boarding school. Temple Grove, located in Eastbourne in Brian’s day, sounds rather an austere establishment, with no electricity or heating. Brian, who was a rather fussy and predictable eater throughout his life, found the food particu -larly awful, and supplemented his diet with Marmite. Years later, I remember him asking Nancy, the much-loved chef whose kitchen was directly below our commentary box in the Pavilion at Lord’s, for a plate of Marmite sandwiches as a change from his usual order of roast beef, which he used to collect from her every lunchtime. Brian appears to have remembered Temple Grove for two reasons: the matron had a club foot, and the headmaster, the Reverend H.W. Waterfield, a glass eye. How did he know he had a glass eye? ‘It came out in conversation!’

Although cricket was Brian’s first love, it seems that he might have been more successful at rugby, in which he was a decent fly-half. He kept wicket for the first XI in his final two years at Temple Grove – he always referred to wicketkeepers as standing ‘behind the timbers’ – and was described in a school report as ‘very efficient’ and unfailingly keen. His batting appears to have been rather eccentric, and he was a notoriously poor judge of a run. This might explain his excitement during commentary on Test Match Special at the prospect of a run-out, and especially at the chaos invariably created by overthrows, which he always referred to as ‘buzzers’. This appears to be very much, although not exclusively, an Etonian expression. Henry Blofeld, like Johnners an Old Etonian, remembers ‘buzzers’ rather than ‘overthrows’ being the term of choice in matches involving the old boys, the Eton Ramblers. Like Johnners, Henry always describes buzzers with particular relish.

From Temple Grove, Brian went on to Eton, which he loved, and remembered as being like a wonderful club. It was there that he discovered he could make people laugh, and also where it is believed he started his unusual habit of making a sound like a hunting horn from the corner of his mouth. We often heard this from the back of the commentary box, usually in the form of two gleeful ‘whoop whoops’ whenever he detected even the faintest whiff of a double entendre in the commentary, or just to amuse himself. ‘It’s amazing,’ Trevor Bailey observed once of an excellent delivery from the Pakistani fast bowler Waqar Younis, ‘how he can whip it out just before tea.’ Rear of commentary box: ‘Whoop whoop!’

As was the case at prep school, cricket was Brian’s particular love at Eton, although he still seemed to be more successful at rugby. He proudly told the story of being surely the only player in the history of the sport to score a try while wearing a mackintosh. This occurred while he was at Oxford. He lost his shorts while being tackled, and had retired to the touchline and put on the coat ‘to cover my confusion’, as he put it. The ball was passed down the three-quarter line and Brian out rageously reappeared on the wing, mackintosh and all, to score between the posts. Oh, to have seen that.

Inevitably, Brian’s dream in his final summer at Eton in 1931 was to represent the first XI and to play against the school’s great rivals, Harrow, in the traditional two-day showpiece at Lord’s. This was almost as much of a date in the calendar of the social elite as it was a cricket match, and it was the ambition of every cricketer at both schools to make the cut. But Brian never did, and as would be the case with his sacking from the BBC television commentary team many years later, he deeply resented the fact, and often spoke quite openly about it. He laid the blame firmly at the feet of one Anthony Baerlein, who had kept wicket for the Eton first XI for the previous two years. Brian always held the firm belief that Baerlein should have left school at the end of the summer term, allowing Brian a free run at his place behind the timbers in his final year. But according to Brian, Baerlein, with an eye on a third appearance at Lord’s, decided to stay on an extra year, and dashed Brian’s hopes. (Records show that Baerlein was indeed nineteen and a half years old when he, rather than Johnners, played against Harrow in the summer of 1931, but also that he had arrived at Eton in 1925, and was therefore in the same year as Brian. He would go on to become a novelist and journalist before joining the RAF in the Second World War. He was killed in action in October 1941, at the age of just twenty-nine.)

During his time at the famous old school Johnners made many lifelong friends, and the Eton connection would provide him with invaluable contacts later on; not least – and most conveniently – Seymour de Lotbiniere, who happened to be head of Outside Broadcasts when Brian applied for his first job at the BBC. Brian was late for the interview, which was very unusual for a man who in my experience was a fastidious timekeeper. It turns out that he had been given the wrong time for his appointment, but the Old Etonian ‘Lobby’ gave him the job anyway.

At the time Brian left Eton, everything seemed to be pushing him towards the family coffee business, but he already knew this was not for him. He was not particularly enthusiastic about university, but managed to secure a place at New College, Oxford. He claimed this was achieved more on the back of his father having been there than because of any academic merit or even potential. At least it meant delaying the apparently inevitable career in coffee, which would also mean a lengthy spell living in Brazil. He read History at Oxford, gained a third-class degree and very obviously had a good time. Cricket featured highly, but so too did practical jokes, which usually involved his partner in crime William Douglas-Home, who had been at Eton with him and whose older brother Alec would later become Prime Minister. The pair would dress up, often disguising themselves, and cause various degrees of mayhem, not least when Douglas-Home lost his driving licence and, as an emergency, hired a horse and carriage and appointed Brian his groom. (Douglas-Home’s offence, incidentally, was no more than parking without sidelights, suggesting, possibly controversially, that traffic wardens have mellowed over the years.)

What a sight it must have been as the mischievous pair steered this contraption through the middle of Oxford. The first proper outing involved being taken by ‘Lily’ – named after the Lady Mayor of Oxford – to buy a newspaper; it ended in chaos when they found it impossible to turn the carriage around, and caused a major traffic jam. In time and with practice, Brian and Douglas-Home became adept at handling Lily and the carriage, and they even travelled to lectures in this manner. Lily became a familiar figure in Oxford, and the police gave her precedence at crossroads.

The comical image this conjures up is Brian to a T: larger than life, outrageous and definitely slightly ridiculous, but also more than sufficiently confident to pull it off. These traits would all manifest themselves when it came to performing in his regular live radio slot in Let’s Go Somewhere in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Brian was much more widely known as an entertainer than as a cricket commentator, and was involved in such pranks as hiding in a postbox and startling members of the public who had been urged to post their Christmas cards early, and even carrying out a robbery on a jeweller’s shop in Nottingham. Looking back, it beggars belief that Brian was able to convince the powers that be that he should be allowed actually to stage a burglary, live on radio. The Chief of Nottingham Police was in the know, but nobody else. Of course, Brian kept up a running commentary throughout the entire madcap adventure, even while smashing the shop window and stealing a silver cup, and right up to the point of his eventual arrest by a humourless constable after a lengthy car chase. In typical Brian fashion, he was able to pass off the whole exercise as a demonstration of how wonderful our police force is, when in fact it was an absurd piece of almost childish escapism.

It seems that Brian’s only disappointment at Oxford was, once again, falling short on the cricket front. He was playing up to four times a week, for the Oxford Authentics, which is the university club team, for I Zingari, a nomadic team very much for the well-heeled, and for the Eton Ramblers. This must have affected his studies, but he did not come close to earning a much-coveted blue. Although he captained his college team for two seasons from behind the timbers, it seems that he was not good enough to play for the university.

The three years at Oxford passed all too quickly, and once again the question of Brian’s career was thrust into the spotlight. One of his school friends, Lord Howard de Walden, had suggested to Brian during their teens that he should become a broadcaster – almost entirely due to the fact that he never stopped talking. Bearing in mind that the BBC was only founded in 1922, when Brian was ten, and that broadcasting was pretty rudimentary while the boys were growing up, this showed remarkable foresight and perception. But Brian apparently shrugged it off. If he was moved towards anything – and that is debatable – he wanted to be an actor. What he did not want to do was to pursue a career as a coffee merchant in the family business.

Nevertheless, within two years he was indeed despatched to Santos, an island port off the Brazilian coast with a dreadful reputation for yellow fever. He had at least learned the art of coffee-tasting during a brief apprenticeship in London, which included a short posting to pre-war Hamburg, where he was taken to listen to a tub-thumping speech by Josef Goebbels. He was based in Kensington, staying with his uncle, Alex Johnston, in a house that sounds like something out of Upstairs, Downstairs. Certainly there was a substantial staff that Brian was quick to befriend, a particular favourite being the butler, Targett. Brian and Targett would meet below stairs for games of crib-bage which included Edward the footman and a one-legged tailor, who would remove his wooden leg and carefully lodge it under the table for the duration. Edward reappeared after the war when Brian married Pauline, working as Brian’s valet and ironing his shirts once a week. Brian’s son Barry tells me that he also served the drinks at the Johnstons’ much anticipated annual summer parties before he was fired for becoming incapably drunk in the course of one such event, and was last seen being bundled unceremoniously into the back of a taxi.

Much more significant in this brief interlude while he was learning about coffee beans was that Johnners fell passionately in love with music-hall comedy. He devoted much of his time in London to the theatre, watching the best comedians on stage. His favourites were Flanagan and Allen, who as well as being a double act in their own right were also members of the Crazy Gang, and Max Miller, whose risqué brand of humour particularly appealed to Brian. It was during these often solitary evenings that Brian’s love of word-play de -veloped, and while in Brazil he took to amateur dramatics, probably for the first time; there is no evidence of his having performed in so much as a single school play either at Temple Grove or at Eton, which is something of a surprise considering he was such a natural showman, and hardly the shy and retiring type. These productions, which Brian essentially ran himself, were far and away the highlight of what was clearly a miserable experience. Brian admits to having been pretty useless at his job: he could hardly tell the coffee beans apart, and consequently was never given a position of any authority or responsibility. Within eighteen months he was struck down by peripheral neuritis, a nasty-sounding illness affecting the nervous system which all but paralysed him. So serious was his condition that his mother had to travel to Santos and take him home. A poor diet, and a lack of vegetables in particular, is believed to be one of the primary causes of peripheral neuritis, so Brian’s fussy eating may have played its part. Unlike at prep school, there was no supply of Marmite to fall back on.

Brian’s convalescence saw him reunited with William Douglas-Home for more pranks and more cricket. He saw the 1938 Australians, including the innings of 240 by Wally Hammond for England in the second Test at Lord’s which, during those inevitable commentary box discussions when rain stopped play, Brian always determinedly ad -vocated as being one of the greatest Test innings of all time. He was soon back at work as assistant manager in the coffee business, and although he still hated the job he was now twenty-six, and much as he resented it, the prospect of a lifetime in coffee trading loomed realistically large. Indeed, had it not been for the outbreak of the Second World War the following year, that might very well have been his destiny.

With a group of fellow Old Etonians, Brian signed up with the Grenadier Guards shortly after Germany invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939 – his cousin happened to be in command of the 2nd Battalion. He was drilled at Sandhurst, although it tests the imagin -ation somewhat to imagine Johnners marching and saluting with absolutely razor-sharp military precision. But, back in the ‘boys together’ environment he had so enjoyed at school and at university, Brian felt liberated and able to express himself in a way that he never could in an office. He was clearly excellent entertainment in the officers’ mess, where he would often sing ‘Underneath the Arches’, perhaps the most famous song of Flanagan and Allen, just about accompanying himself on the piano. The song would remain a lifelong favourite of his: he sang it live on Test Match Special with Roy Hudd, the comedian and music-hall singer, who he was interviewing for ‘A View from the Boundary’ in the final Ashes Test of 1993. I remember it well: the unaccompanied duet drifting through the open window of the old commentary box at The Oval in a passable impersonation of Flanagan and Allen, their mutual heroes. Poignantly, this would be Brian’s last match on Test Match Special. He died five months later.

In May 1940 Brian was preparing to join the 2nd Battalion in France when it was evacuated from Dunkirk. After a brief period in charge of the motorcycle platoon, which he led from a sidecar brandishing a pistol – I suspect he loved this enormously – he became Technical Adjutant in the newly formed armoured div -ision. Brian was not the least bit technically minded, and his first challenge was to learn about the workings of a tank engine. With two of his fellow trainees – one of whom was the future Conservative Deputy Prime Minister and Home Secretary William Whitelaw, the other Gerald Upjohn, later the Lord Justice of Appeal, Lord Upjohn – Brian was given an engine and told to strip it down and reassemble it. The first task was a good deal easier than the second, but finally their engine was apparently rebuilt, although there remained several pieces that they simply could not account for. Looking around the room, Brian and Whitelaw could see the inspecting officer ser iously reprimanding any trainees who had attempted to hide surplus engine parts or nuts and bolts, so at Brian’s instigation they decided to pop their leftovers into Upjohn’s pocket. Come the inspection, Brian and Whitelaw duly turned out their pockets with absolute confidence, while the unfortunate Upjohn found himself handing over an unfeasible number of redundant nuts and bolts to an increasingly agitated inspector. It fell to Upjohn to find homes for all the remaining parts while Brian and Whitelaw were given leave to retire to the NAAFI.

Action for Brian started three weeks after the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944. His battalion had been due to sail with the main force, but bad weather delayed their departure. His first encounter with the Germans was on 18 July, and in his autobiography he wrote powerfully and graphically about the experience.

The heat and the dust, the flattened cornfields, the ‘liberated’ villages which were just piles of rubble, the refugees, the stench of dead cows, our first shelling, real fear, the first casualties, friends wounded or killed, men with whom one had laughed and joked the evening before, lying burned beside their knocked-out tank. No, war is not fun, though as years go by one tends only to remember the good things. The changes are so sudden. One minute boredom or laughter, the next, action and death. So it was with us.

Essentially, Brian’s job was to rescue and recover the tanks that had been damaged on the battlefield. In practice this meant physically pulling burning and horribly injured colleagues from their wrecked machines as battle raged around him. So dismissive was Brian of the Military Cross he was awarded towards the end of the campaign that he would claim it was more or less given out with the rations. In fact, the MC is the third-highest military decoration, awarded to officers in recognition of ‘an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy’. To treat it as a sort of handout was typical of Brian, who would genuinely have been embarrassed to have dwelt on his own acts of bravery, and certainly would in no way consider himself to be a hero. Unusually, although not uniquely, Brian’s MC was awarded not for a single incident, but more for his consistent attitude and contribution throughout what was clearly a ghastly situation. His citation included the words: ‘His own dynamic personality, coupled with his untiring determination and cheerfulness under fire, have inspired those around him always to reach the highest standard of efficiency.’

Just as Brian chose not to talk about the tragic and distressing circumstances of his father’s death, his time in the army was a topic of conversation we never shared. In his talk at the school when I was at Uppingham, and later in his supposed retirement when he toured the country’s theatres with An Evening with Johnners, his entire army career of six years was more or less dispensed with in three jokes.

When the war ended, it is fair to say that Brian had no idea what to do with his life. He was now thirty-three years old, and knew that a return to the coffee trade was out of the question. The trouble was that while he wanted to be involved in ‘entertainment’, nothing particularly interested him. A chance reunion with two BBC war correspondents, Stewart MacPherson and Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, who Brian had met during the war, led to his interview with the Old Etonian Seymour de Lotbiniere at Outside Broadcasts. Although Brian did not seem to be entirely convinced, he agreed to take part in two tests that can hardly be described as taxing. In the first, he simply had to commentate on what he could see going on in Piccadilly Circus; the second involved interviewing members of the public in Oxford Street about what they thought of rationing. It is fair to say that his performances did not set the world alight, but he was nevertheless regarded as promising enough to be offered a job, starting on 13 January 1946. So began a career in broadcasting that was to last almost fifty years.

At the time Brian joined the BBC, the flagship Saturday-evening programme In Town Tonight attracted a staggering twenty million listeners or more every week. Entire families would crowd around the radio to listen to the studio-based magazine programme featuring interviews and music, including a brief three-and-a-half-minute live segment. This was the slot that Brian inherited from John Snagge, but now made his own, and his off-the-cuff, unscripted and often daring broadcasts to millions of people earned him his fame and his reputation.

Many of these live broadcasts have passed into folklore, although I do think the naïvety of the audience in those early days did give Brian a sizeable opportunity for hamming things up a bit – something he certainly would not have shied away from. There was the night he spent in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s, during which he claimed to be terrified as he cowered amongst the waxworks of mass murderers, executioners and their victims. Yet this was a man who had only recently been under fire, winning the Military Cross. And there would certainly have been BBC technicians with him in the Chamber of Horrors. The whole episode was surely skilfully laced with Brian’s love of dramatics. A rather braver episode was lying beneath the track outside Victoria Station in a pit about three feet deep, and commentating as the Golden Arrow, en route from Paris, thundered overhead. Unfortunately, the Golden Arrow was running a few minutes late that evening, so after quite a build-up Brian had to make do with a comparatively dull suburban electric train, which nonetheless sounded very impressive as it passed over him, with Brian barely audible as he described the impressive shower of sparks. In An Evening with Johnners he would claim that when the delayed Golden Arrow finally rattled overhead, someone happened to flush the toilet and absolutely soaked him, although I suspect this was another case of entirely harmless Johnston creativity.

Live broadcasting in those days must have been a hairy business of poor communications, failed live crossings and all manner of technical mishaps. The best presenters would have been those who could remain calm, or lucid at least, when everything was falling down all around them. Maybe the post-war attitude, as famously expressed by the great Australian cricketer and fighter pilot with the Royal Australian Air Force, Keith Miller, was a contributing factor. When asked about handling the pressure of a situation in a particular cricket match, Miller scoffed: ‘Pressure? Pressure’s having a Messerschmitt up your arse!’

It was in 1946, during his first year at the BBC, that Johnners was first approached to commentate on cricket. This began as little more than a gentle enquiry from an old friend, Ian Orr-Ewing, who was now head of Outside Broadcasts at BBC television, which in those days was little more than a fledgling operation. Only four Test matches had been broadcast on television before the war, but Orr-Ewing was now planning to show the 1946 series against India. Brian was a staff man at Outside Broadcasts, and was known to love cricket; those credentials proved to be more than enough to get him the job.

It must have been a terribly exciting time – these were the pioneering days of television commentary, with no rules or experience to fall back on. Brian’s colleagues in the box included the former Surrey and England captain Percy Fender, whose nose was equally prominent as Brian’s, and R.C. Robertson-Glasgow, who had played for Somerset and was one of the leading writers on cricket of the time. I suspect this environment was not unlike that of my early days on the new digital television networks. All the equipment was in place, but only a tiny audience was watching, so it was a perfect way to learn the trade without too many people witnessing one’s mistakes.

BBC Radio had been broadcasting cricket reports since 1927, and Howard Marshall began providing commentary in short chunks in 1934. He was joined by E.W. (Jim) Swanton, and later by Rex Alston, and in 1946, the same year that Brian started in the television commentary box, John Arlott was recruited by BBC Radio. Despite the BBC having the personnel to broadcast a full day’s play, there were still only short periods of commentary until 1957, when for the first time an entire Test match, against the West Indies, was broadcast. A new programme needed a new name: Test Match Special. It was not until he became the BBC’s cricket correspondent in 1963 that Brian started to appear occasionally on Test Match Special, sharing his radio duties with television, despite regularly touring overseas for BBC Radio from the winter of 1958 until he retired as cricket correspondent in 1972.

Despite often living on the edge, in broadcasting terms at least, Brian was always capable of laughing at himself. He absolutely adored cock-ups, and in those early days of broadcasting these must have been many and often. One I distinctly remember him mentioning in his Uppingham speech all those years ago involved Wynford Vaughan-Thomas rather than himself, but he told the story with tremendous enthusiasm, and as was his wont, he could not help but laugh along too.

This gaffe occurred when Queen Elizabeth, later to become the Queen Mother, launched HMS Ark Royal at Birkenhead in 1950. Vaughan-Thomas was reporting the event for BBC television, and was briefed by the producer that there were three cameras. The first would show the Queen officially naming the ship, breaking the bottle of champagne against the hull. He was not to speak at this stage, or indeed during the second shot, which would be of the Marine band playing and the crowd cheering. Camera three would then show the Ark Royal slipping slowly down the ramp, and only when it finally entered the water could Vaughan-Thomas start his commentary. Everything went perfectly until the third shot, when, with the Ark Royal sliding down the ramp, the producer saw that camera one had a lovely picture of the Queen smiling serenely and waving to the crowds, so he switched the picture from camera three to camera one. Vaughan-Thomas failed to check his monitor as the Ark Royal hit the water, and with televisions all around the country showing a full-sized frame of a beaming Queen, Vaughan-Thomas said: ‘There she is, the huge vast bulk of her!’

That story brought down the Uppingham School hall, and would later feature in Brian’s theatre show. Little did he know that sitting in the audience that day was a schoolboy with whom, almost a quarter of a century later, he would combine to create an even more notorious broadcasting cock-up. Johnners would then always use what has become known as ‘The Leg Over’ as the climax to his speeches, as indeed I do today. But that afternoon in the mid-1970s, as I walked back to my boarding house with my mates chuckling at the stories we had just heard, I had no idea that this wonderful entertainer and I would one day be colleagues.