Читать книгу Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life - Jonathan Bate - Страница 18

10 ‘So this is America’

ОглавлениеWith summer gone, they took up residence in the town of Northampton, on the banks of the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts. This was the location of Smith College, where Sylvia taught as an instructor for freshman English throughout the 1957–8 academic year. They lived in an apartment at 337 Elm Street, near a church, a high school and the green oasis of Childs Memorial Park. After a nervous first day, fastened in the straitjacket of a blue flannel suit that Ted remembered in a Birthday Letters poem, Sylvia threw herself into her teaching. Busy as she was preparing and taking classes, she continued to plan ‘Falcon Yard’, her Cambridge novel. Ted helped to steer her away from the superficial externals of her magazine-style prose, towards his own more inward territory. ‘Place doesn’t matter – it’s the inner life: Ted & me,’ she reminded herself in her journal.1 But for Ted, place did matter. ‘So this is America’ was his memory of his thought on first making love to Sylvia.2 Now he was in America with his American wife.

In her imagination, Sylvia was still in England. She planned short stories. One of them, ‘Four Corners of a Windy House’, sketched out in ‘physical, rich, heavy-booted detail’ their bracing hike across the moors to Top Withens:

blisters, grouse – picnic – honey soaking through brown paper bag – fear, aloneness – goal – cairn of black stones, small, contracted – their dream of each other, she & he … Strength – each alone – bracken, marsh – tea in deep cleft of valley – dark, cats – story of lost woman – match-flare of courage in the dark – moor sheep – bus-wait opposite spiritualists – ghosts & reality on moor … house: absolute reality, but clustered with ghosts – eternal paradox of identity.3

Before his eyes, Ted’s life was being transformed into art through his wife’s magical gift for words.

He, on the other hand, felt blocked. With Sylvia as the breadwinner, he was free to write full time, but the poems had dried up. He would sit for hours ‘like a statue of a man writing’.4 The only difference between him and an inanimate figure was that after a few hours a bead of sweat would drip down his forehead. For the first time, he was trying to write as opposed to writing down the words that just came to him. And it was the trying that proved the impediment. What was more, the fact of having published all the decent poems he had written meant that he had to move on to a new style. There would be no point in producing a second book that was just like the first – and it was on the basis of a second book that his long-term literary future would be judged. He cooked Sylvia both breakfast and lunch, but the life of idleness was not for him. He wandered around Northampton and was disconcerted by the Smith girls, who went around in gaggles, all looked like each other, and had a ‘machined glaze of hyper-health’.5 Later in the year, an encounter with some of them in Childs Memorial Park seems to have provoked an angry outburst from Sylvia.6

Ted sensed that, paradoxically, he would be more productive if he had less time on his hands. So he began to look for a job. The trouble was, there was nothing interesting for him to do in the dull town of Northampton. He made some enquiries about part-time work for the college radio station in nearby Amherst.

The Hawk in the Rain was published in London by Faber and Faber on 13 September 1957, at a price of ten shillings and sixpence, in an edition of 2,000 copies in a yellow dust jacket with narrow blue stripes, the title in blue and ‘poems by Ted Hughes’ in red.7 The American edition appeared five days later, in a smaller edition, at a price of $2.75. A month later, Ted and Sylvia went to New York for a reading and launch party at the Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y, which had been the country’s leading venue for live poetry since 1939. Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood had had its premiere there.

Sylvia wrote to his parents afterwards, telling them that Ted had done a wonderful job, looking extremely handsome in his only suit (dark grey) and the golden yellow tie she had bought him in Spain for his birthday the previous year. She had persuaded him, much against his will, to have a haircut, so he looked like ‘a Yorkshire god’. There were about 150 people in the audience, and he ‘read beautifully’.8 Some members of the audience bought the book beforehand and followed the poems on the page as he read. Afterwards, he signed autographs, using Sylvia’s shoulder as a writing-desk. In the same letter, she thanked her in-laws for the mother-of-pearl earrings they had just sent her for her twenty-fifth birthday: these would go perfectly with the pink woollen dress that she had worn on her wedding day. She also told them that she had persuaded Ted to write an autobiographical children’s story about a little boy who lived on the moors that he so loved.

Ted in turn wrote excitedly to Dan Huws, saying that the 92nd Street Y had been packed for his reading and that afterwards he was ‘swamped by dowagers’ who wanted to know why ‘Bawdry Embraced’ – those rollicking verses from their Cambridge days – had not been included in the book. The answer was that Marianne Moore had considered them ‘too lewd’ and insisted on the poem being dropped.9 An assortment of ‘maidenly creatures’ asked him to sign their fresh copies of his slim volume. One of them took the book back after he had signed it, looked at him with wide eyes and said, ‘And what I want to say is “Hurrah for you”.’10 This was his first full experience of the effect his poetry readings would have on females in the audience.

Reviews came more quickly in Britain than America. One of the first was by the distinguished Orcadian poet Edwin Muir in the New Statesman: ‘Mr Ted Hughes is clearly a remarkable poet, and seems to be quite outside the current of his time.’ His voice was very different, that was to say, from the urbane tones of the poets of the so-called Movement – the anti-romantic, anti-Dylan Thomas group, including Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis and Donald Davie, whose work had been gathered the previous year in an anthology called New Lines. ‘His distinguishing power is sensuous, verbal and imaginative; at his best the three are fused together,’ Muir continued. ‘His images have an admirable violence.’ All in all, The Hawk in the Rain was ‘A most surprising first book, and it leaves no doubt about Mr Hughes’s powers.’11 He said that Hughes’s ‘Jaguar’ was better than Rilke’s ‘Panther’, praise so high that Ted thought it would be more likely to provoke ‘derision than curiosity’.12

The reviews that counted most were those in the New York Times and the London Observer. They appeared on the same day, 6 October. The New York account was by a poet who would soon become a very good friend, W. S. Merwin. He could hardly have been more positive. The book’s publication, he wrote, gave reviewers ‘an opportunity to do what they are always saying they want to do: acclaim an exciting new writer’. The poems were more than promising. They were ‘unmistakably a young man’s poems’, which accounted for ‘some of their defects as well as some of their strength and brilliance’, but ‘Mr Hughes has the kind of talent that makes you wonder more than commonly where he will go from here, not because you can’t guess but because you venture to hope.’13

Later in the autumn, they met Merwin. Ted found him impressively ‘composed’. His English wife Dido was, according to Sylvia, ‘very amusing, a sort of young Lady Bracknell’; to Ted, she seemed ‘bumptious garrulous upper class’.14 They were introduced through Jack Sweeney, director of the Woodberry Poetry Room in the student library at Harvard. Sweeney gave lively dinner-parties for local and visiting poets at his home on Beacon Street in Boston. Ted arrived with a limp and his foot in plaster, because he had fractured the fifth metatarsal in his right foot when jumping out of an armchair in the Elm Street apartment at a moment when his foot had gone to sleep. He was still limping when he struggled up the stairs some time later to the Merwins’ fifth-floor apartment on West Cedar Street, for another dinner-party, at which Bill Merwin suggested that Ted and Sylvia should move back to England, because the opportunities for BBC broadcasting, together with newspaper and magazine reviewing, would give them much more time for their own writing than they would have staying in America, where the only way that poets could make a living was through distracting and debilitating university teaching. The Merwins were heading to London themselves.

In London, it was Al Alvarez, poetry editor of the Observer, who could make or break a young writer. He wrote poems himself – Ted thought they were ‘very crabby little apples’ – and he wasn’t easy to please. His review dropped a lot of names in a manner that Ted considered ‘undergraduatish’ – D. H. Lawrence, Thom Gunn, Robert Lowell, Shakespeare’s Coriolanus (from which he accused Hughes of stealing the word ‘dispropertied’).15 Alvarez criticised some of the poems for being excessively ‘literary’ or having a ‘misanthropic swagger’, but said that half a dozen of them could only have been written by ‘a real poet’.16

Alvarez’s judgement was astute. Some of the poems in The Hawk in the Rain now read like period pieces. There is sometimes a clever literary allusiveness that does not feel real. And pieces such as ‘Secretary’ are unpleasantly misanthropic – or in this case, misogynist. Quite a lot of the poems are directly or indirectly about sex, viewed from a very masculine perspective. But there are indeed half a dozen pieces of true genius. Four of them are among the first five in the collection: ‘The Hawk in the Rain’, ‘The Jaguar’, ‘The Thought-Fox’ and ‘The Horses’. The two other highlights are ‘Wind’, which begins with the memorable line ‘This house has been far out at sea all night,’17 and ‘Six Young Men’. This was inspired by a photograph of a group of friends posing near the bridge at the top of Crimsworth Dene, that favourite spot of Ted’s. They are all ‘trimmed for a Sunday jaunt’ some time just before the outbreak of war. The ‘bilberried bank’, ‘thick tree’ and ‘black wall’ were all still there, forty years on, but the young men were not. ‘The celluloid of a photograph holds them.’ The image is ‘faded and ochre-tinged’, yet the figures themselves are free from wrinkles. ‘Though their cocked hats are not now fashionable, / Their shoes shine.’ A shy smile is caught in one of the faces, another of the lads is chewing a piece of grass. One is shy, another ‘ridiculous with cocky pride’. Little differences, but the same end: ‘Six months after this picture they were all dead.’18 The poem remains one of the two best retrospectives on the ‘never such innocence again’ motif of the beginning of the Great War, the other being Philip Larkin’s ‘MCMXIV’, published a few years later in The Whitsun Weddings.

The hawk, the jaguar, the thought-fox and the horses all seem perfectly formed: animal images seamlessly entering the inner self of the poet. But Ted’s notebooks reveal that all were struggled for, through draft after draft. So, for example, it was a tremendous trial to reach the shimmer of the line ‘Steady as a hallucination on the streaming air’ in the title poem:

As a hallucination in the avalanche of air untouched

As a hallucination in the heaving air buoyed

Like a hallucination in the swamping air to its sides

Like a hallucination the running air

Like a hallucination that the scene rides and it hangs

Like a hallucination that the scenes rides <vivid> through …

After these six failed attempts, he got to ‘Steady as a hallucination in the bursting sky’, but still that was not quite right.19 Again, it was a long time before he achieved ‘The window is starless still; the clock ticks, / The page is printed’ at the end of ‘The Thought-Fox’. First he had to create and reject such variants as ‘And the page where the prints have appeared’ and ‘The clock crowding and the whitening sky / Watch this page where the prints remain.’20

There were warning signs. Sylvia was exhausted by her duties at Smith. Ted told Olwyn that she was working twelve hours a day and cracking under the strain. Sometimes she would descend from the manic energy of her writing into days when she struggled to get out of bed, what with coughs and colds, fevers and flu, or sheer torpor. Christmas with Aurelia was marred by Sylvia suffering from viral pneumonia, exacerbated by her exhaustion from teaching and marking. In the new year, she told her head of department that she wanted to leave at the end of the academic session instead of accepting her option to stay on for a second year. Ted, meanwhile, got a similar teaching position for the semester over at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

He had to teach two classes three times a week on a ‘Great Books’ course. This meant mugging up on Milton’s shorter poems, including Samson Agonistes, reading Goethe’s Faust for the first time (opportune because he had been enthusing about Goethe and Nietzsche in a letter to Olwyn the previous autumn), getting advice from Sylvia about Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (they both heavily annotated their battered copy of the Penguin paperback of the English translation),21 plunging into that quintessentially New England book, Thoreau’s Walden, and going back to some of his favourite poetry – Wordsworth, Keats and Yeats. He also had to teach freshman English twice a week and a creative writing class in which he could do more or less what he liked. As a handsome young instructor with a relaxed teaching style, a rich English accent and a prizewinning first book of poems just published, he was an immediate hit with his students, especially the female ones. In the creative writing class, there were just eight of them, ‘3 beautiful, one brilliant & a very good person’.22

Back at Elm Street, despite all the preparation and marking, there was plenty of time for reading. Ted had some success in persuading Sylvia to share his Yeatsian occult interests, though these were more to Olwyn’s taste. He read through the Journals of the Psychical Research Society from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and wrote to her of ‘wonderful accounts of hypnoses, automatic writings, ghosts, double personalities etc’. He was delighted to find an anticipation of his own belief that the left side of the brain (in right-handed people) controlled ‘all consciously-practised skills’, whereas ‘the subconscious, or something deeper, a world of spirits’ was located in the right lobe.23

In April, Ted gave a poetry reading at Harvard. They drove down in the car they were borrowing from Warren Plath while he was away in Europe on his Fulbright scholarship. Sylvia’s ex-lover, the poet and publisher Peter Davison, remembered the ‘emphatic consonant-crunching of Hughes’s voice’ when he read.24 The effect was to emphasise the nouns and underplay the verbs. As his poetry developed, Ted would often take the opportunity to omit some of the verbs altogether, even on paper. At a reception afterwards, they were introduced to several poets and writers. The literary scene in Cambridge and Boston was much more lively than that in Northampton and Amherst, so they felt justified in a plan they were hatching to move there in the summer.

Not that they had failed to find a few like-minded people during their teaching year. Several would remain particular friends: the poet Anthony Hecht was a member of the Smith faculty and the British poet and classical scholar Paul Roche was on a visiting fellowship, accompanied by his American wife Clarissa. Then in May 1958, they met the artist Leonard Baskin and his family. Eight years older than Ted, and with a comparably dark imagination, he taught printmaking and sculpture at Smith. ‘How I love the Baskins,’ Sylvia would write in her journal the following summer. They were ‘a miracle of humanity and integrity, with no smarm’.25 For Ted, too, Baskin would always remain the model of uncompromising artistic integrity. His volatile temper and forceful opinions were a necessary part of the package.

Sylvia’s adoration of Ted and his poetry was undimmed. In March he did a public reading at the University of Massachusetts, coming on third, after two very inferior local poets. He ‘shone’, she wrote, ‘the room dead-still for his reading’. Her eyes filled with tears and the hairs on her skin stood up like quills: ‘I married a real poet, and my life is redeemed: to love, serve and create.’26 When her own writing was going well, she dared to imagine that she might one day be ‘The Poetess of America’ as Ted would certainly be ‘The Poet of England and her dominions’. She thought he was infallible in his suggestions for improvements in her poems, even down to the alteration of odd words such as ‘marvelingly’ instead of ‘admiringly’.27

Just before the end of the semester, the mood suddenly changed. Their new friend Paul Roche, the visiting poet and classicist, had arranged a public reading of his new translation of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. Ted agreed to play the part of Creon, but he told Sylvia that he would prefer it if she did not attend. There had been no rehearsals and he did not have any confidence in the production. At the last minute, Sylvia did decide to go. She slipped into a seat at the back. For the first time, she didn’t like the look of Ted: he appeared slovenly, ‘his suit jacket wrinkled as if being pulled from behind, his pants hanging, unbelted, in great folds, his hair black and greasy’ under the stage lights. Afterwards, he went backstage, frustrated with himself for agreeing to be inveigled into the evening. Paul Roche wondered whether he was grumpy because he thought he could have done a better job on the translation himself. With one finger, Ted banged out a tune on an old piano. It was probably a mistake not to have greeted Sylvia straight after the show: she was beginning to grow suspicious of Ted, not wanting to be apart from him for even an hour at a time. That semester there were rumours about all sorts of affairs going round the English Department. Something about his manner wasn’t right. He wouldn’t speak to her, but wouldn’t leave. He had what she called an ‘odd, lousy smile’ of a kind she hadn’t seen since Falcon Yard – was this the smile of the man who had taken Shirley to the party and ended up in a fierce embrace with Sylvia? In her journal she asked herself whether his behaviour could really be explained by his being ‘ashamed of appearing on the platform in the company of lice’.28

The next day was the final day of teaching before the long summer break. Sylvia got a great round of applause from both her morning and her afternoon classes. Ted agreed that he would drive down to the Smith campus, return his library books and meet Sylvia to celebrate the end of term. He had time on his hands, since he had taught his last class at Amherst a day or two before. Sylvia had twenty minutes to spare before the afternoon class, so she went into the campus coffee shop. She noticed one of her male colleagues deep in flirtatious conversation with a very pretty undergraduate. This got her thinking about liaisons between professors and their students, which were not at all uncommon, especially in an English department at an all girls’ college. After class, she went to look for Ted in the car park. Their car was there, but it was empty. Thinking he had gone to return his books, she drove it towards the library.

Suddenly she saw Ted, ‘coming up the road from Paradise Pond where girls take their boys to neck on weekends’. He had a broad smile on his face and was – as Sylvia saw it – gazing into the ‘uplifted doe-eyes of a strange girl with brownish hair, a large lipsticked grin, and bare thick legs in khaki Bermuda shorts’. When Sylvia appeared, the girl made a very hasty exit. Ted made no effort to introduce her. ‘He thought her name was Sheila’ (actually it was Susan).29 Had he not once, Sylvia wrote in a bitter diary entry, thought that her name was Shirley? Everything seemed to fall into place: the unfamiliar smile, the excuses for returning home late. Suddenly, the God, the great poet, the only man she could ever want, was ‘a liar and vain smiler’. They made up and made love, but afterwards, as he snorted and snored beside her, she lay awake, wondering, doubting. Why was his ‘great inert heavy male flesh hanging down so much of the time’? Yes, there were ‘such good fuckings’ when they did make up, but why had he been sexually ‘so weary, so slack all winter’? That had not been characteristic. Was he ‘ageing or spending’? ‘Fake. Sham ham. No explanations, only obfuscations’: she was seeing again ‘the vain, selfish face’ she had first seen. The ‘sweet and daily companion’, the lovely ‘Yorkshire Beacon boy’, was gone. Now she could only think of his sulks, his selfishness, his greasy hair, the foul habits that she could not stand, obsessed as she was with personal hygiene (picking his nose, ‘peeling off his nails and leaving them about’). Their marriage was over. She wouldn’t slit her wrists in the bath or drive Warren’s car into a tree or, to save expense, ‘fill the garage at home with carbon monoxide’, but, ‘disabused of all faith’, she would throw herself into her teaching and writing.30

Ted never published his side of the story, but many years later he did scribble a note about it. The ‘big handsome girl’ was in his creative writing class. She called herself ‘Spring’. He had always found her very friendly, but she ‘kept her distance’. He did feel a certain ‘affinity’ with her (having admitted this, he scored it out). He liked all his students in the little creative writing group. After his last class, this girl and her friend produced a bottle of red wine and three glasses, just as he was hurrying off to drive back from Amherst to Northampton. He excused himself and left them standing crestfallen. He did not expect ever to see any of his students again. By sheer coincidence, when he went to meet Sylvia on the Smith campus the following day, he bumped into the girl, coming out of the library with a bunch of other girls. So he walked with her for a few minutes. And that was when Sylvia appeared.31 From his point of view, the encounter was entirely innocent and Sylvia’s rage worryingly irrational.

They fought violently. There were ‘snarls and bitings’. Sylvia ended up with a sprained thumb and Ted with ‘bloody claw-marks’ that lasted a week. At one point, she threw a glass across the room with all her might. Instead of breaking, it bounced back and hit her on the forehead. She saw stars for the first time.32

The fight cleared the air. They were intact. ‘And nothing,’ Sylvia wrote, ‘no wishes for money, children, security, even total possession – nothing is worth jeopardizing what I have which is so much the angels might well envy it.’33 If she could learn not to be over-dependent, not to require ‘total possession’, things would work out.

Reflecting on the incident when undergoing psychoanalysis six months later, she recognised that Ted was not habitually spending time with other women. There was no reason not to trust him. She had reacted so forcefully because the end of her exhausting teaching year was a big moment and she had wanted him to be there for her, and he wasn’t. His absence, she reasoned, with the assistance of her analyst, must have made her think of her father, who had deserted her for ever by dying when she was eight. Insofar as he was ‘a male presence’ – though ‘in no other way’ – Ted was ‘a substitute’ for her father. ‘Images of his faithlessness with women’ accordingly echoed her father’s desertion of her mother upon the call of ‘Lady Death’.34 Any act of male rejection or desertion, however temporary, would have an extreme effect because it would take her unconscious back to the primary trauma of Otto’s sudden disappearance into death. This line of thinking would crystallise in some of her later poems and give Ted lifelong food for reflection in both prose and verse.

That summer they had a week’s holiday in New York and a fortnight revisiting Cape Cod, but otherwise they were in the apartment on Elm Street, writing. Or trying to write – they both suffered from bouts of block. In search of inspiration or relaxation, they took to experimenting with a Ouija board, conjuring up a spirit called Pan.

Two years after the whirlwind romance and the rushed wedding, the reality of married life was kicking in. ‘We are amazingly compatible,’ Sylvia reassured herself. ‘But I must be myself – make myself and not let myself be made by him.’ She was beginning to tire of his tendency to give mutually exclusive ‘orders’. He would tell her to – or, to put it more moderately, suggest that she should – ‘read ballads an hour, read Shakespeare an hour, read history an hour, think an hour’. But then he would say that no proper reading could be done in one-hour chunks; you had to read a book straight through to the end without distraction. There was an almost fanatical ‘lack of balance and moderation’ in his habits and his fads. He decided that, since he sat writing for much of the day, he should do some particular exercises for his back and his neck. They only made his neck stiffer, but that didn’t stop him doing them.35

On the eve of Independence Day, they went for a walk and found a baby bird that had fallen out of its nest. Ted took it home and nursed it, just as he always used to care for injured fauna in his childhood. After a week, it became clear that the bird would not survive. Sylvia could not bear the thought of Ted strangling it, so he fixed their rubber bath hose to the gas jet on the cooker and taped the other end on the inside of a cardboard box. The bird was laid to rest, but unfortunately he removed it from the makeshift gas chamber prematurely and it lay gasping in his hand. Five minutes later, he took it to Sylvia, ‘composed, perfect and beautiful in death’.36

In early September they moved to a tiny sixth-floor apartment at 9 Willow Street in the Beacon Hill district of Boston, with all its literary associations. Ted’s poem named for the address evokes the claustrophobia they felt there, the sense that they were holding each other back instead of inspiring each other’s work as they had done before. The main memory within the poem is a variant replay of the baby-bird incident. This time it is a sick bat that has fallen out of a tree on the nearby Common. In front of a bemused audience of passersby, he tries to restore it to its home and has his finger bitten for his pains. Then he remembers that American bats carry rabies, so he starts thinking of death.37 His other Birthday Letters poems commemorating their residence in Willow Street are equally gloomy: visiting Marianne Moore, Sylvia devastated because the distinguished poet did not like her work; Sylvia and her ‘panic bird’; the ‘astringency’ of the Charles River in a bitterly cold Boston winter.38

One day, looking over a letter from his wife to his parents before posting it, he misread the signing off as ‘woe’ instead of ‘love’.39 This seemed symbolic of the new mood in the marriage. Sometimes when his writing was not going well, he would while away the afternoon making a wolf mask. But that did nothing to keep the wolf from the door: the plan to live for a year off their savings, together with such casual literary earnings as they could muster, meant that they sometimes fought, because it wasn’t always clear where the next month’s dollars were coming from. They both sensed that the marriage had no future in America; Ted had not settled and Sylvia did not want to go back to teaching. There were days when they both suffered from ‘black depression’, relieved only by sporadic absorption in Beethoven piano sonatas.40

This was when she began seeing Dr Ruth Beuscher, her old psychoanalyst from McLean. Among her many worries was the fear that she was barren. Beuscher was a Freudian. She suggested that the main focus of their sessions should be Sylvia’s ‘Electra complex’, the daughterly equivalent of the Oedipus complex. They explored the hatred that Sylvia had projected on to her mother following her father’s death. That anger was by this time mixed up with a feeling that Aurelia was undermining the marriage by means of her constant complaints about Ted not having a proper job. ‘I’ll have my own husband, thank you,’ Sylvia wrote in her diary, as if addressing her mother. ‘You won’t kill him the way you killed my father.’ Ted had ‘sex as strong as it comes’. He supported her in body and soul by feeding her bread and poems. She loved him and wanted to be always hugging him. She loved his work and the way he was always changing and making everything new. She loved the smell of him and the way their bodies fitted together as if they were ‘made in the same body-shop to do just that’. She loved ‘his warmth and his bigness and his being-there and his making and his jokes and his stories and what he reads and how he likes fishing and walks and pigs and foxes and little animals and is honest and not vain or fame-crazy’. ‘And’, she goes on, ‘how he shows his gladness for what I cook him and joy for when I make something, a poem or a cake, and how he is troubled when I am unhappy and wants to do anything so I can fight out my soul-battles’.41

Life wasn’t all bad. There was fresh fish. Luke Myers came through on a short visit, and they reminisced about Cambridge days. Ted and Sylvia were both getting poems accepted. Ted heard that he had won the Guinness Poetry Award (£300) for ‘The Thought-Fox’. He received a treasured letter of congratulations from T. S. Eliot at Faber and Faber. The grand old man said how impressed he had been when he first read the typescript of the book and how delighted he was to have Ted on the Faber list.42 And in Boston there was the proper literary scene that they craved: a reading by Truman Capote, dinner-parties with Robert Lowell, intense discussions about poetry at the apartment of poet Stanley Kunitz (Ted did most of the talking, Sylvia sitting quietly with a cup of tea), a meeting with the now old and rather deaf but still legendary Robert Frost. Ted loved hearing stories about one of his favourite poets, the very English Edward Thomas, who had been inspired by Frost to turn from prose to verse only a couple of years before his death on the Western Front.

Sylvia sat in on Lowell’s poetry classes at Boston University, and he read both her work and Ted’s. Lying on the bed in the Elm Street apartment earlier in the year, Ted had written a poem called ‘Pike’. Lowell said it was a masterpiece.43 Leonard Baskin admired it too, and reproduced 150 copies of it privately under his personal imprint, the Gehenna Press. This was Ted’s first ‘broadside’. The title was in red, the poem in black, and there was an illustrative woodcut by an artist friend of Baskin’s, portraying two pike, one in black and the other in green. ‘Pike’ also appeared in a group of five immensely powerful Hughes poems in the summer 1959 issue of a magazine called Audience: A Quarterly of Literature and the Arts. The four others were ‘Nicholas Ferrer’, ‘Thrushes’, ‘The Bull Moses’ and ‘The Voyage’. A couple of months earlier, another magazine had published ‘Roosting Hawk’, which he had written sitting at his work-table one morning in Willow Street. He told his parents that he was finding that the key to a creative day was an early night and an early start. He was hitting his stride and would soon have enough good poems for a second collection. He was also starting work on a play. They went to tea with Peter Davison in his apartment across the Charles River in Cambridge. He gave Ted a copy of Jung’s The Undiscovered Self, which chimed perfectly with the ideas he was exploring. ‘The Jung is splendid,’ he told Davison in his thank-you letter, ‘one of the basic notions of my play.’44

In January 1959 they acquired a tiger-striped kitten and called it Sappho. She was said to be a granddaughter of Thomas Mann’s cat, a suitably literary pedigree. In April, Ted won a $5,000 award from the Guggenheim Foundation, in no small measure due to the support of Eliot. He wrote to thank him, signing off the letter with a dry allusion to the famous opening line of The Waste Land: ‘I hope you are well, and enjoying April.’45

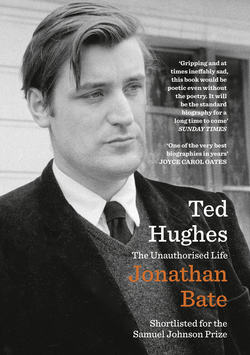

While living in the cramped Willow Street apartment, they were visited by Rollie McKenna, a diminutive Texan portrait photographer who was a genius with a Leica III camera fitted with a Japanese Nikkor screw lens of the kind used by Life magazine photographers in the Korean War. She had immortalised Dylan Thomas in two images, one with pout and cigarette, the other ‘bound, Prometheus-like, in vine-tendrils (his idea), against the white wall of her house in America’.46 Now she would capture Ted and Sylvia in images that would be published in the year of Plath’s death in a book called The Modern Poets: An American–British Anthology, which included a real rarity in the form of a photograph of T. S. Eliot that he liked. The photograph of Ted, somewhat in Fifties Teddy-boy mode, shows him tanned, relaxed, leaning back, his tie artfully dishevelled but his hair for once swept back without the trademark lick over his forehead. His eyes melt the spectator. Ted and Sylvia were also photographed at work together: husband and wife as Team Poetry.

That spring saw the publication of Life Studies, Robert Lowell’s first new volume for eight years. It was immediately recognised as a literary landmark. For one thing, it contained a distinctive mix of poetry and short prose memoirs. For another, in contrast to the intricate formality of Lowell’s earlier work, the poems moved seamlessly between metrical regularity and free verse. The language had a new informality and the subject matter was frequently very personal.

A review in the Nation by the critic M. L. Rosenthal described the book as ‘confessional’. The name stuck and Lowell, quite unintentionally, found himself labelled as the leader of a new school of American poetry. For Ted and Sylvia, it was exciting to be around Lowell at this time. Sylvia found in Life Studies a licence to write more direct poetic confessions of her own. Ted deeply admired the technical accomplishment, but was more sceptical about the personal content. ‘He goes mad occasionally,’ Ted told Danny Weissbort in a letter about Lowell, ‘and the poems in his book, the main body of them, are written round a bout of madness, before and after. They are mainly Autobiographical.’ At the heart of the collection was ‘Waking in the Blue’, Lowell’s great poem about his period of confinement in a secure ward at the McLean mental hospital: ‘We are all old-timers, / Each of us holds a locked razor.’47 ‘AutoBiography [sic]’, Ted concluded his sermon inspired by Life Studies, was ‘the only subject matter really left to Americans’. The thing about Americans was that their only real grounding was their selves and their family, ‘Never a locality, or a community, or an organisation of ideas, or a private imagination’.48 He was thinking about Sylvia as well as Lowell.

In a letter to Luke Myers written a couple of months later, he focused on a different aspect of contemporary American poetry, reflecting on William Carlos Williams’s preoccupation with ‘sexy girls, noble whores, the flower of poverty, tough straight talk’ and describing E. E. Cummings (whom he considered a genius, a fool and a huckster) as ‘one of the first symptoms and general encouragements of the modern literary syphilis – verseless, styleless, characterless all-inclusive undifferentiated yelling assertion of the Great simplifying burden-lifting God orgasm – whether by drug, negro, masked nympho or strange woman in the dark’.49 His own recent poetry, by contrast, was combining a tough American assurance with the earth-grounded English eye of Hawk, without going into free form or confessional mode.

If there was a like-minded American poet, it certainly wasn’t someone in the tradition of ‘electronic noise’ coming out of the suicidal Hart Crane, whom Lowell in Life Studies called the Shelley of his age. Rather, it was the Southern agrarian John Crowe Ransom. Behind every word of Ransom’s poetry, Ted told Luke, repeating some of the Leavisite language of their Cambridge days, ‘is a whole human being, alert, sensitive, reacting precisely and finely to his observations’. As for British poetry, it needed to get back to this kind of wholeness, the tight weave of ‘the thick rope of human nature’, which had been found in the old ballads, in Chaucer, Shakespeare, Webster, Blake, Wordsworth, Keats, the dialect poems of Burns, but virtually no one since. For a century and a half the English sensibility had got too hung up on ‘the stereotype English voice’ of the gentleman.50 What was needed was a distinctly ungentlemanly tone and matter, a new poetry of working-class roots and rural rootedness. This is what he was developing in his new book, which was nearing completion. The name of D. H. Lawrence is strikingly absent from the genealogy outlined here: perhaps out of a certain ‘anxiety of influence’, Ted is suppressing the name of the writer who came immediately before him as a northern, working-class voice with a sensitivity to the raw forces of nature, an interest in myth and archetype, an unashamed openness of sexual energy, and a distinctly lubricious attitude to the female body (Lawrence was the poet who compared the ‘wonderful moist conductivity’ of a fig to a woman’s genitals).51

Leonard Baskin agreed to consider doing a design for the cover of the new book. Ted gave him a lead by suggesting that the ‘general drift’ of the poems could be summed up as ‘Man as an elaborately perfected intestine, or upright weasel’.52 Ted proposed Baskin to Faber, but did not get the response he wanted; they went for a geometric dust-wrapper design instead. In a separate development, though, Faber did accept ‘a book of 8 poems for children’, each of which was about a relative: a sister who was really a crow, an aunt devoured by a thistle, and so on. It was published under the title Meet My Folks!

Ted jokingly told Charles Monteith, his editor at Faber, that it was his own equivalent of Lowell’s Life Studies, which had included intense poems of family memory and marital discord with such titles as ‘My Last Afternoon with Uncle Devereux Winslow’, ‘Grandparents’ and ‘Man and Wife’. It would be a long time before Ted started publishing pieces about his family, let alone his marriage, in this ‘confessional’ voice.

Ted and Sylvia received a joint invitation to spend two months in the autumn at Yaddo, a rural retreat for writers in upstate New York. Though invited to apply, their proposals still had to be graded by the writers who were Yaddo’s assessors (Richard Eberhart, John Cheever and Morton Zabel). Both applications received a good mix of As and Bs.53 They were in.

They decided that, before taking up residence and then returning to England, they should set off to see America. They packed boxes for the journey, boxes in readiness for Yaddo and boxes for home. Ted wrote to his parents, telling them in great detail (complete with a little drawing) about the tent they had bought, discounted from $90 to $65. It had a sewn-in waterproof groundsheet, something unheard of in the camping days of his youth, and even a meshed window. Aurelia Plath bought them air mattresses that folded down to the size of pillowcases and thick puffy sleeping bags with zips all round (meaning that they could be joined together for cuddles on chilly nights in the wild). She threw in an assortment of other camping gadgets for good measure, and they had a trial night sleeping in the tent on the back lawn of her house in Elmwood Road, Wellesley. Ted pronounced it as comfortable a night as he had ever had. Any apprehensions that cleanliness-minded Sylvia would not be the camping type were swiftly dispelled. They said goodbye and off they went in Aurelia’s car, on a ten-week road trip through mountain, prairie and desert, all the way to California and back.

First they headed for the Great Lakes, crossing the Canadian border into Ontario. They took snapshots of each other by the tent and the waterside. In the Algonquin Provincial Park, Sylvia looked happier than she had ever looked, as a deer took blueberries from her hand. Then they went west to Wisconsin, where they camped by Lake Superior in the field of a kindly Polish fisherman near a village with the wonderful name of Cornucopia. His daughter took them fishing, but there wasn’t much in the way of catch, since lampreys had eaten nearly all the trout in the lake.

Then it was across the prairies, under big skies and through the Dakota Badlands. There were fierce electric storms, the earth was a sinister red. It was a place where seams of lignite ignited spontaneously, burning slowly for years or even centuries, turning the clay soil to brick shale. The land reeked of sulphur and tar. ‘This is evil,’ Ted remembered Sylvia saying. ‘This is real evil.’ There seemed to be some strange consonance between this America and the dark recesses of her mind. ‘Maybe it’s the earth,’ she said, or ‘Maybe it’s ourselves.’ The emptiness seemed to be sucking something out of them, the dark electricity within ‘Frightening the earth, and frightening us’.54 ‘The Badlands’, which went through dozens of drafts before reaching its final form in Birthday Letters, was one of his first poems in the loose style of a journal.

Stepping further westward, they crossed Montana. This was real cattle country, empty wilderness, not unlike the Yorkshire Moors, but with grass and richer soil, and without any valleys. At roadside cafés, you got ‘steak the size of a plate, home-made berry pie piled with icecream, your coffee cup filled up as fast as you emptied it (for the price of just one cup)’.55 This was the real America, the generous and friendly people real Americans. After a long drive southwards, they arrived at the Yellowstone National Park, which was becoming more famous than ever with the advent on television the previous year of the animated cartoon character Yogi Bear. Ted told his parents that it was like the Alps, but with bears. They counted nineteen on the road in the first 30 miles after entering the National Park. The bears would wander up to people’s cars and stand on their hind legs, hoping for food. ‘People get regularly mauled, trying to feed them,’ Edith and Bill were informed.56 On their first night in the park, Ted heard one sniffing round their tent, which was only 10 feet from a trash can.

On the second night they returned at dusk from a drive around the Grand Loop of the park, seeing the geysers and the hot pools, only to find a large black bear standing over their trash can. It lumbered off when it was caught in their headlights. They locked their food in the boot of the car and washed down the picnic table and benches. At ‘the blue moonlit hour of quarter to three’ Sylvia was woken from a dream in which their car was blown to pieces with a great crash. The crashing sound was real: her first thought was that a bear had smashed open the car with a great cuff and started eating the engine (a seed here for Ted’s story about the metal-devouring Iron Man?). Ted, also woken by the crash, had the more prosaic thought that the bear had knocked their cooking pans off the picnic table. They lay listening to ‘grunts, snuffles, clattering can lids’. Then there was ‘a bumpity rolling noise as the bear bowled a tin’ past their tent. Sylvia peered out of the tent screen and, ‘not ten feet away’, saw a huge bear ‘guzzling at a tin’. In the morning they discovered that the noise was that of ‘the black-and-gilt figured cookie tin’ in which they kept their fruit and nut bars. Though they had secured most of their food in the boot, this had been on the back seat of the car inside Sylvia’s closed red bag. The bear had smashed the car window, torn the bag open and found the tin, which it had also managed to open. The bag had also contained Ritz crackers and Hydrox cookies, which had been eaten, and a selection of postcards, which she found in the morning among the debris left from the visit. The top card, a picture of moose antlers, was turned upside down. And a postcard of a bear was face up on the ground with the paw print of an actual bear on it.57

Having consumed the contents of the cookie tin, the bear had gone away. Ted and Sylvia had lain awake, terrified that it might come back and rip its way into their tent. It did indeed return, just as dawn broke. Ted stood up and looked out of the window of the tent to see it slurping away at the oranges that they had left on the ledge behind the back seat of the car. ‘It’s the big brown one’, he told Sylvia. They had heard that this was the nasty sort. Scared off by the sound of ‘The Camp Ranger’s car, doing the morning rounds’, it ran away, tripped on a guy rope and nearly tumbled into Ted and Sylvia’s tent.58

The story went around the camp. A Yellowstone regular told them to smear the tent with kerosene because bears hated the smell. Someone else suggested red pepper, but they decided that the best thing would be to move to a campsite higher up the hillside and not too close to any garbage cans. Ted appended a handwritten postscript to Sylvia’s typewritten letter home: ‘Well, I wanted to tell about the bear, but Sivvy’s done that better than I even remembered it.’59

In the washroom, Sylvia told the story to another woman, who replied that the bears were particularly bad that year. On the Sunday night, just before Ted and Sylvia’s arrival in the park, another woman had tried to scare one off with a flashlight and been mauled to death. This gave Sylvia the idea of, in Ted’s later phrase, transforming their own ‘dud scenario into a fiction’.60 ‘The Fifty-Ninth Bear’ is one of her most effective short stories. It concerns a couple called Norton and Sadie. Norton was the surname of both a former boyfriend and the character in the television sitcom The Honeymooners whose vocal mannerisms inspired Yogi Bear.61 Sadie was one of the names Sylvia thought of using for the autobiographical protagonist of ‘Falcon Yard’. They count fifty-eight bears as they drive round the Grand Loop at Yellowstone. When they are woken in the night by the sound of another bear, Norton goes outside and sees the smashed car window. He waves a flashlight to scare the bear away, but is cuffed over the head and killed: ‘It was the last bear, her bear, the fifty-ninth.’ The sinister aspect of the story is that Norton’s arrogance has in some sense made Sadie want him to die: in daydreams, he imagined himself as a widower,

a hollow-cheeked, Hamletesque figure in somber suits, given to standing, abstracted, ravaged by casual winds, on lonely promontories and at the rail of ships, Sadie’s slender, elegant white body embalmed, in a kind of bas relief, on the central tablet of his mind. It never occurred to Norton that his wife might outlive him. Her sensuousness, her pagan enthusiasms, her inability to argue in terms of anything but her immediate emotions – this was too flimsy, too gossamery a stuff to survive out from under the wings of his guardianship.62

Ted gave his own version of the story in the longest poem in Birthday Letters, also called ‘The 59th Bear’. In the rear-view mirror of memory, he vividly revisited ‘the off rear window of the car’,

Wrenched out – a star of shatter splayed

From a single talon’s leverage hold,

A single claw forced into the hair-breadth odour

Had ripped the whole sheet out. He’d leaned in

And on claw hooks lifted out our larder.

He’d left matted hairs. I glued them in my Shakespeare.63

Whereas Sylvia’s story exits the husband to death, pursued by the fifty-ninth bear, Ted captures a trophy of the animal encounter and gives it to his Shakespeare. One may assume that he pasted the matted hairs somewhere near the famous stage direction in The Winter’s Tale. He ended the poem by reflecting on Sylvia’s short story, reading the bear as an image of the death that was hurtling towards her rather than her husband.

After leaving Yellowstone, they drove through the Grand Teton mountain range, stopping for photographs, then south to Salt Lake City and Big Cottonwood Canyon, where, as a reward after their immensely long drive, they treated themselves to a huge meal of Kentucky fried chicken, rolls and honey, potatoes and gravy. They swam in the great Salt Lake, discovering with amazement and delight that you really didn’t sink, could almost sit up on the water as if in an armchair. Then it was across the desert into the sunset, passing into Nevada, where they stopped for the night to camp, Sylvia cooking the last of their Yellowstone trout, ‘with corn niblets, a tomato and lettuce salad and milk’.64 At last they reached California, camping near Lake Tahoe, then stopping in ‘the lovely palm-tree shaded Capitol Park of Sacramento’ – ‘the site of the mine that started the gold rush’ – in 114-degree heat.65 They liked the holiday feel of California, the mix of mountains, forests, fertile farmland. Sylvia wrote of the lushness, Ted of the fruit.

At last they reached the sea, intending to camp at Stinson Beach State Park, just over 20 miles outside San Francisco. But their guidebook was out of date. The supposed campsite had been turned into a parking lot. Sylvia, desperately tired from yet another mammoth drive, was on the verge of tears. Ted suggested that they should try their luck in town. They had cold beer and fried chicken at a café and the generous owner suggested that they park their car in his lot and sleep under the stars on the beach. For Sylvia, it was one of the best nights of her life, not least because she sensed new life quickening inside her. Her period was due and it had not yet come. Away from the stress of Smith, she had become pregnant early in the summer.

Ted did not quite share the sense of climax. He wrote several drafts of a poem about Stinson Beach under the title ‘Early August 1959’, but did not include it in Birthday Letters. ‘We got to the Pacific,’ he wrote. ‘What was so symbolic about the Pacific?’ Whatever it was, they had made it. But the sunset wasn’t as spectacular as it should have been and it was foggy when they woke up in the morning. Still, they had ‘kept to the programme of romance / Slept in our sleeping bags under the stars / Tried to live up to the setting’. He was then cheered when ‘a phone-call from within sight of the sea’ brought the news that Faber and Faber had accepted his second volume of poetry.66 They were not sure about his proposed title ‘The Feast of Lupercal’, because there had been two recent novels of exactly that name (one of them a Faber bestseller), so he decided to call it ‘Lupercalia’ instead.67

They dipped into San Francisco to get the car window repaired. Then it was a beach camp halfway to Los Angeles, then a relaxing stay with Sylvia’s Aunt Frieda in Pasadena. Her hot water and other amenities were much appreciated and her name, with its echo of D. H. Lawrence’s feisty wife, gave them an idea for the baby, should it prove to be a girl. Their eastward journey began with the Mojave Desert and the Grand Canyon. At that grandest of all sights, ‘America’s Delphi’, they sought a blessing on the baby in Sylvia’s womb as a reward for their pilgrimage. Navajo dancers, standing on the rim of the greatest gorge in the world, beat a drum, sounding an echo that thirty years later Ted imagined he could hear, faintly, in the voice of his daughter.68 The primitive power of the drumbeat would become a key resource in his theatre work. More prosaically, when they returned to the car their water-cooling bag, which had crossed the Mojave slung under the front bumper, had been stolen.

From the Grand Canyon they drove all the way across to New Orleans, then north to Tennessee to stay with Luke Myers’s family. The gigantic trip ended with sightseeing in Washington DC and a stay with Sylvia’s Uncle Frank near Philadelphia, before they at last returned home to the hot tubs and home baking of New England. Aurelia thought that they both looked tanned and well, but Sylvia was tired and worried about the pregnancy. She had a history of gynaecological complications, so she still did not feel sure that there really was a baby growing inside her.

Yaddo is an artists’ community located on a 400-acre estate in Saratoga Springs. It was founded in 1900 by a wealthy financier called Spencer Trask and his wife, Katrina, who wrote poetry herself. Left without immediate heirs by the deaths of their four young children, the Trasks decided to bequeath their palatial home to future generations of writers, composers, painters and other creative artists. Katrina had a vision of generations of talented men and women yet unborn walking the lawns of Yaddo, ‘creating, creating, creating’. The idea was to nurture the creative process by providing an opportunity for artists to work without interruption in peaceful, green surroundings. The great American short-story writer John Cheever would write that the ‘forty or so acres on which the principal buildings of Yaddo stand have seen more distinguished activity in the arts than any other piece of ground in the English-speaking community and perhaps the world’.69

When Ted and Sylvia arrived just after Labor Day, the main house had been closed for winter. They were given spacious rooms in the clapperboard West House, among the trees. Each of them had a separate ‘studio’, Sylvia’s on the top floor of the house and Ted’s out in the woods – the perfect place for him. ‘A regular little house to himself’, Sylvia wrote to her mother, ‘all glassed in and surrounded by pines, with a wood stove for the winter, a cot, and huge desk’.70 A writing hut away from the main house would be his salvation at Court Green in later years. The chance to live together but work apart was exactly what they needed. Meals were taken care of and the food was very good, a welcome change from the campground cookery of the summer. Breakfast was available from eight till nine, lunchboxes were then collected and taken to each resident’s studio, and in the evening they all gathered for dinner. Being a quiet season, there were only a dozen artists in residence, including painters, an interesting composer and a couple of other poets whose names were not familiar to them.

One of the painters, Howard Rogovin, did portraits of both Sylvia and Ted. For Sylvia, he set up his easel in the old greenhouse. To the sound of ‘rain in the conifers’, he painted Sylvia lifted out of herself ‘In a flaming of oils’, her ‘lips exact’. But he also seemed to catch a shadow on her shoulder, a dark marauding ‘doppelgänger’.71 At one point, a graceful snake slid across the dusty floor of the hot greenhouse. Both this portrait and the one of Ted, which was said to be less successful, are lost.72

The composer was Chou Wen-chung, a United States immigrant from Shandong in China. A protégé of the radical experimentalist Edgar Varèse, he sought to integrate Eastern and Western classical (and modernist) musical traditions. They struck up a friendship and Ted began work on a libretto for him, for an oratorio based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The original title, Bardo Thödol, literally means ‘Liberation through Hearing during the Intermediate State’. These ‘intermediate states’ included the dream state, the moment of death in which the clear light of reality is experienced, and the ‘bardo of rebirth’, which involved hallucinatory images of men and women erotically entwined. The project was never finished, but it took Ted into territory that he would make his own in almost all his later mythic works.73

His main project at Yaddo was his play (now lost, save for a few fragments), ‘The House of Taurus’. Sylvia described it in a letter home written in early October: ‘a symbolic drama based on the Euripides play The Bacchae, only set in a modern industrial community under a paternalistic ruler’.74 She hoped that it would at least get a staged reading, but explained that she had not yet typed it up.

During the weeks at Yaddo Ted also revised one or two of the poems in his forthcoming ‘Lupercalia’ collection, but for poetic development it was more of a breakthrough moment for Sylvia. Before Yaddo, her verse had been highly accomplished but somehow brittle. A self-description in a journal entry of late 1955 was harsh but apt: ‘Roget’s trollop, parading words and tossing off bravado for an audience’ (Roget’s Thesaurus was the vade mecum of writers looking for unusual words for ordinary things).75 Very few Plath poems written before Yaddo stick in the mind; almost all the hundred or so that Sylvia wrote thereafter sear themselves into the consciousness of the attentive reader. Years earlier, Plath had dreamed of gathering forces into a tight tense ball for the artistic leap. At Yaddo, she made that leap.

On 10 October 1959, she wrote in her journal: ‘Feel oddly barren. My sickness is when words draw in their horns and the physical world refuses to be ordered, recreated, arranged and selected. When will I break into a new line of poetry? Feel trite.’ It was certainly odd to feel barren when she was at last pregnant. Then on the 13th: ‘Very depressed today. Unable to write a thing. Menacing gods. I feel outcast on a cold star.’ Ted told her to ‘get desperate’. On the night of the 21st, she felt ‘animal solaces’ as she lay with him, warm in bed. The next day, walking in the woods in the frosty morning light, she found the ‘Ambitious seeds of a long poem made up of separate sections: Poem on her Birthday. To be a dwelling on madhouse, nature. The superb identity, selfhood of things. To be honest with what I know and have known. To be true to my own weirdnesses.’76 Madhouse, nature, identity, self, weirdness: in ‘Poem for a Birthday’, Sylvia began for the first time to write poetry overtly about her suicide attempt, mental breakdown and electro-convulsive therapy, albeit refracted through a symbolic narrative of descent and rebirth.

Within a fortnight the sequence was ‘miraculously’ written. The title came from the fact that her birthday fell halfway through the process of composition. What was it that released the flow? The example of Lowell confronting his nervous breakdown in Life Studies was crucial. Ted, who was convinced that this was indeed the turning point in her poetic career, pointed to the influence of the poetry of Theodore Roethke, which she read in the Yaddo library (where she also renewed her acquaintance with the wonderfully confident and supple poetry of Elizabeth Bishop). Conversations with Ted about the death and rebirth structure of Bardo Thödol would also have played a part. But her journal offers other clues. It reveals that she was ‘electrified’ by the consonance between the imagery she was developing and the language of Jung’s Symbols of Transformation, another book in the well-stocked Yaddo library. And a couple of days earlier, her creativity released by some breathing exercises that Ted taught her, she had written two poems that pleased her, one to ‘Nicholas’, the name they had chosen for their child if it proved to be a boy, and the other on ‘the old father-worship subject’.77 The father who had died when she was eight and the unborn child in her womb. She was on a cusp, about eighteen weeks pregnant. Did the baby quicken and give its first kick at this time? Before her stood tomorrow.

They returned to Wellesley just before Thanksgiving. Sylvia was now noticeably pregnant. Aurelia later remembered Ted working away in the upstairs bedroom while Sylvia ‘sorted and packed the huge trunk’ that they had set up in the breezeway. On the day they left, ‘Sylvia was wearing her hair in a long braid down her back with a little red wool cap on her head.’ She looked like a teenage girl going off to boarding school. As the train pulled out of the station, Ted shouted out, ‘We’ll be back in two years!’78 He was looking forward to home, and English beer, having found the American variety ‘unspeakable and unspewable’.79

On a clear blue day in March 1959, Ted and Sylvia had gone out from their little Willow Street apartment to Winthrop, the southernmost point of Boston’s North Shore. In the morning, Sylvia had been with her psychoanalyst, probing further at her feelings about her dead father. It was time, they decided, for her to visit Otto Plath’s grave in Winthrop for the first time. When they found it, she felt cheated by the plain and unassuming flat stone, tempted to dig him up in order to ‘prove he existed and really was dead’.80

Then they walked over some rocks beside the ocean. The wind was bitter. Their feet got wet and they picked up shells with cold hands. Ted walked alone to the end of the bar, in his black coat, ‘defining the distance of stones and stones humped out of the sea’.81 Afterwards, Sylvia wrote a poem called ‘Man in Black’. It was soon accepted by the New Yorker, one of her first big successes in getting her work into high-profile print. It catches the moment: the breakwaters absorbing the force of the sea, the March ice on the rock pools, ‘And you’ – Ted, that is – striding out across the white stones:

in your dead

Black coat, black shoes, and your

Black hair …82

There he stands, a ‘Fixed vortex’ on the edge of the land, holding it all together, the stones, the air, Sylvia’s life and her father’s death. The line-break catapults the word ‘dead’ into double sense. At one level, Ted’s coat is dead black in the sense of pitch black. At another level, it is black because black is the colour of death. Sylvia’s black imagination has indeed dug Otto out of his grave – and reincarnated him in her husband.

That is how Ted read the poem. In Birthday Letters, he made a point of placing his reply-poem, which he called ‘Black Coat’, after the long journal-like poems about the road trip. In terms of strict chronology, it should have been before. But he wanted to make it into a summation of their time in America. He places himself looking across the sea, ready for home. He remembers the moment in the Algonquin Provincial Park when he had photographed Sylvia feeding a wild deer with freshly picked blueberries. Something about the idea of a camera makes him uncomfortable. It is the same sensation as that provoked by the sinister image behind Sylvia’s shoulder in the portrait that Howard Rogovin had painted in the Yaddo greenhouse. A shadow, a double, a whisper of death. He then imagines Sylvia taking a photograph of him. Perhaps she had brought a camera to snap her father’s grave, or perhaps it is the metaphoric photograph of the poem ‘Man in Black’ that is entering her mind at this moment. Either way, he feels as if he has stepped ‘Into the telescopic sights / Of the paparazzo sniper’ nested in Sylvia’s brown eyes. He feels as if she is pinning him with a ‘double image’, ‘double exposure’ (the name she would choose three years later for her lost novel about the disintegration of their marriage). He feels as if her dead father has just crawled out of the sea. He ‘did not feel’ Otto sliding into him as Sylvia’s ‘lenses tightened’.83

Or at least all this is what he thought he thought when, years later, he began to write the series of letter-poems that first took their overall title from the deer, then from the black coat, and finally from the poem that Sylvia had written at Yaddo, ‘for a Birthday’.