Читать книгу Pax - Jon Klassen - Страница 10

Оглавление

“So there were lots of them.”

Peter heard how stupid it sounded, but he couldn’t help repeating it. “Lots.” He plowed his fingers through the heap of plastic soldiers in the battered cookie tin – identical except for their poses: standing, kneeling, and prone, all with rifles pressed hard to their olive-green cheeks. “I always thought he just had the one.”

“No. I was always stepping on them. He must have had hundreds. A whole army of them.” The grandfather laughed at his own accidental joke, but Peter didn’t. He turned his head and looked intently out the window, as if he had just caught sight of something in the darkening back yard. He raised a hand to draw his knuckles up his jaw line, exactly the way his father rasped his beard stubble, and wiped surreptitiously at the tears that had brimmed. What kind of a baby cried about something like this?

And why was he crying at all, anyway? He was twelve and he hadn’t cried for years, not even when he’d fractured his thumb bare-handing Josh Hourihan’s pop fly. That had hurt a lot, but he’d only cursed through the pain waiting with the coach for X-rays. Man up. But today, twice.

Peter lifted a soldier from the tin and drifted back to the day he’d found one just like it in his father’s desk. “What’s this?” he’d asked, holding it up.

Peter’s father had reached over and taken it, his face softening. “Huh. Been a long time. That was my favourite toy when I was a kid.”

“Can I have it?”

His dad had tossed the soldier back. “Sure.”

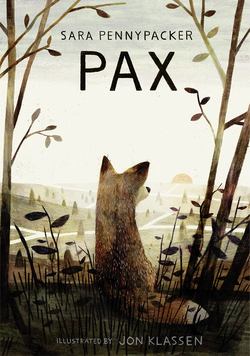

Peter had stood it up on the windowsill beside his bed, pointing the little plastic rifle out in a satisfying show of defence. But within the hour Pax had swiped it, which made Peter laugh – just like him, Pax had to have it.

Peter dropped the toy back into the tin and was about to snap the lid back on when he noticed the edge of a yellowed photo sticking up from the mound of soldiers.

He tugged it free. His dad, at maybe ten or eleven, with one arm draped around a dog. Looked like part-collie, part-a-hundred-other-things. Looked like a good dog, the kind you would tell your own son about. “I never knew Dad had a dog,” he said, passing the photo to his grandfather.

“That’s Duke. Dumbest creature ever born, always underfoot.” The old man looked more closely at the picture, and then over at Peter as if seeing something for the first time. “You’ve got the same black hair as your dad.” He rubbed at the fringe of grey fuzz banding the top of his head. “I had it too, way back. And look, he was scrawny then, too, same as you, same as me, with those ears like a jug. The men in our family – I guess our apples don’t fall far from the tree, eh?”

“No, sir.” Peter forced a small smile, but it didn’t hold up. “Underfoot.” That was the word Peter’s father had used. “He can’t have that fox underfoot. He doesn’t move as fast as he used to. You stay out of the way, too. He’s not used to having a kid around.”

“You know, war came and I went and served, like my father. Like your father now. Duty calls, and we answer in this family. No, sir, our apples don’t fall far from the tree.” He handed back the photo. “Your father and that dog. They were inseparable. I’d almost forgotten.”

Peter put the photo back into the tin and pressed the lid down tight, then slid it under the bed, where he’d found it. He looked out the window again. He couldn’t risk talking about pets right now. He didn’t want to hear about duty. And he sure didn’t want to hear any more about apples and the trees they were stuck underneath. “What time does school start here?” he asked, not turning round.

“Eight. They said to show up early, introduce yourself to the homeroom teacher. Mrs. Mirez, or Ramirez … something. I got you some supplies.” The old man nodded over to a spiral notebook, a beat-up thermos, and a bunch of stubby pencils bundled together with a thick rubber band.

Peter walked over to the desk and put everything into his rucksack. “Thanks. Bus or walk?”

“Walk. Your father went to that school, and he walked. Follow Ash to the end, turn right on School Street, and you’ll see it – big brick building. School Street – get it? You leave by seven thirty, you’ll have plenty of time.”

Peter nodded. He wanted to be left alone. “Okay. I’m all set. I guess I’ll go to bed.”

“Good,” his grandfather replied, not bothering to hide the relief in his voice. He left, closing the door behind him firmly as if to say, You can have this room, but the rest of the house is mine.

Peter stood by the door and listened to him walk away. After a minute, he heard the sound of dishes clattering in the sink. He pictured his grandfather in the cramped kitchen where they’d eaten their silent dinner of stew, the kitchen that reeked so strongly of fried onions that Peter figured the smell would outlive his grandfather. After a hundred years of scrubbing by a dozen different families, this house would probably still smell bitter.

Peter heard his grandfather shuffle back along the hall to his bedroom, and then the low spark as the television caught, the volume turned down, an agitated news commentator barely audible. Only then did he toe off his trainers and lie down on the narrow bed.

Six months – maybe more – of living here with his grandfather, who always seemed on the verge of blowing up. “What’s he always so mad about, anyway?” Peter had asked his father once, years ago.

“Everything. Life,” his father had answered. “He got worse after your grandmother died.”

After his own mother had died, Peter had watched his father anxiously. At first, there had just been a frightening silence. But gradually his face had hardened into the permanent threat of a scowl, and his hands clenched in fists by his sides as if itching for something to set him off.

Peter learned to avoid being that something. Learned to stay out of his way.

The smell of stale grease and onions crawled over him, seeping from the walls, from the bed itself. He opened the window beside him.

The April breeze that blew in was chilly. Pax had never been alone outside before, except in his pen. Peter tried to extinguish the last sight he’d had of his fox. He probably hadn’t followed their car for long. But the image of him flopping down on the gravel shoulder, confused, was worse.

Peter’s anxiety began to stir. All day, the whole ride here, Peter had sensed it coiling. It always seemed like a snake to him, his anxiety – waiting just out of sight, ready to slither up his spine, hissing its familiar taunt. You aren’t where you should be. Something bad is going to happen because you aren’t where you should be.

He rolled over and pulled the cookie tin out from under the bed. He fished out the photo of his father with one arm slung so casually around the black-and-white dog. As if he had never worried he could lose him.

Inseparable. He hadn’t missed the note of pride that had entered his grandfather’s voice as he’d said that. Of course he’d been proud – he’d raised a son who knew about loyalty and responsibility. Who knew that a kid and his pet should be inseparable. Suddenly the word itself seemed an accusation. He and Pax, what were they then … separable?

They weren’t, though. Sometimes, in fact, Peter had had the strange sensation that he and Pax merged. The first time it happened had been the first time he’d taken Pax outdoors. The kit had seen a bird and had strained against the leash, trembling as though electrified. And Peter had seen the bird through Pax’s eyes – the miraculous lightning flight, the impossible freedom and speed. He’d felt his own skin thrill in full-body shivers, and his own shoulders burn as though yearning for wings.

It had happened again this afternoon. He had felt the car spin away as though he were the one being left. His heart had quickened with panic.

Tears stung again, and Peter palmed them with frustrated swipes. His father had said it was the right thing to do. “War is coming. It means sacrifices for everybody. I have to serve – it’s my duty. And you have to go away.”

Of course, he’d been half expecting it. Two of his friends’ families had already packed up and left when the evacuation rumours had begun. What he hadn’t expected was the rest. The worst part. “And that fox … well, it’s time to send him back to the wild anyway.”

A coyote howled then, so nearby that it made Peter jump. A second one answered, and then a third. Peter sat up and slammed the window shut, but it was too late. The yips and howls, and what they meant, were in his head now.

Peter had only two bad memories of his mother. He had a lot of good ones, too, and he often took those out to comfort himself, although he worried that they might fade from so much exposure. But the two bad ones he’d buried deep. He did everything in his power to keep them buried. Now the coyotes were baying in his head, unearthing one of them.

When he’d been about five, he’d come upon his mother standing dismayed beside a bed of blood-red tulips. Half of them were standing at attention, half of them splayed over the ground, their blossoms crumpling.

“A rabbit got them. He must think the stems are delicious. The little devil.”

Peter had helped his father set a trap that night. “We won’t hurt him, right?”

“Fine. We’ll just catch him, then drive him into the next town. Let him eat someone else’s tulips.”

Peter had baited the trap himself with a carrot, then begged his father to let him sleep in the garden to keep watch. His father had said no, but helped him set an alarm clock so he’d be the first to awaken. When it went off, Peter had run to his mother’s room to lead her outside by the hand to see the surprise.

The trap lay on its side at the bottom of a freshly scraped crater at least five feet across. Inside was a baby rabbit, dead. There wasn’t a single mark on its little body, but the cage was scratched and dented, and the ground all around clawed to rubble.

“Coyotes,” his father said, joining them. “They must have scared it to death trying to get in. And none of us even woke up.”

Peter’s mother had opened the trap and lifted out the lifeless form. She held it to her cheek. “They were just tulips. Only a few tulips.”

Peter found the carrot, one end nibbled off, and threw it as far away as he could. Then his mother had placed the rabbit’s body in his cupped palms and gone to get a shovel. With a single finger, Peter had traced its ears, unfurling like ferns from its face, and its paws, miraculously tiny, and the soft fur of its neck, slick with his mother’s tears.

When she’d returned, his mother had touched his face, which burned with shame. “It’s okay. You didn’t know.”

But it wasn’t okay. For a long time afterward, when Peter closed his eyes, he’d seen coyotes. Their claws raking dirt, their jaws snapping. He saw himself where he should have been: keeping watch in the garden that night. Over and over, he saw himself doing what he should have: rising from his sleeping bag, finding a rock, and hurling it. He saw the coyotes fleeing back into the darkness, and he saw himself opening the trap to set the rabbit free.

And with that memory, the anxiety snake struck so hard that it stunned Peter’s breath out of him. He hadn’t been where he should have been the night the coyotes killed the rabbit, and he wasn’t where he should be now.

He gasped to fill his lungs and sat bolt upright. He tore the photo in half and then in half again and pitched the pieces under the bed.

Leaving Pax hadn’t been the right thing to do.

He jumped to his feet – he’d already lost a lot of time. He fished some cargos, a long-sleeved camouflage T-shirt, and a fleece sweatshirt from his suitcase, and then an extra set of underwear and socks. He stuffed everything into his rucksack except the sweatshirt, which he tied around his waist. Jackknife in his jeans pocket. Wallet. He debated for a minute between his hiking boots and trainers and decided on the boots, although he didn’t put them on.

He looked around the room, hoping to find a torch or anything resembling camping equipment. The room had been his father’s when he’d been a boy, but aside from a few books on a shelf, it was clear his grandfather had cleaned all his things out. The cookie tin had seemed to surprise him – an oversight. Peter bumped his fingers over the spines of the books.

An atlas. He pulled it down, amazed at his luck, and flipped through it until he came to the map that showed the route he and his father had travelled. “You’ll only be three hundred miles away.” His father had tried to bridge the silence of the drive a couple of times. “I get a day off, I’ll come.” Peter had known that it would never happen. They didn’t give days off in war.

Besides, it wasn’t his father he was already missing.

And then he saw something he hadn’t realised: the highway snaked around a long range of foothills. If he cut straight across those instead of following the highway, he could save a lot of time, plus reduce the risk of being caught. He started to rip out the page, then realised he couldn’t leave his grandfather such an obvious clue. Instead, he studied the map for a long moment, then replaced the atlas on the shelf.

Three hundred miles. It looked like he could shave off a hundred of them by taking the shortcut, so say around two hundred. If he could walk at least thirty miles a day, he could make it in a week or less.

They’d left Pax at the head of the access road that led to the ruins of an old rope mill. Peter had insisted on this road because hardly anyone ever used it – Pax didn’t know about traffic – and because there were woods and fields all around. He’d go back and find Pax there, waiting, in seven days. He wouldn’t let himself think about what might happen to a tame fox in those seven days. No, Pax would be waiting at the side of the road, right where they’d left him. He’d be hungry, for sure, and probably scared, but he’d be okay. Peter would take him home. They would stay there. Just let someone try to make him leave this time. That was the right thing to do.

He and Pax. Inseparable.

He glanced around the room again, resisting the urge to just run. He couldn’t afford to miss anything. The bed. He pulled the blanket off, rumpled the sheets, and punched the pillow until it looked slept on. From his suitcase he took out the picture of his mother he’d kept on his bureau – the one taken on her last birthday, holding up the kite Peter had made for her, and smiling as if she’d never had a better present in her life – and slid it into his rucksack.

Next, he pulled out the things of hers that he’d kept hidden in his bottom drawer at home. Her gardening gloves, still smudged with the last soil she’d ever lifted; a box of her favourite tea, which had long ago lost its peppermint scent; the thick candy-cane-striped kneesocks she wore in winter. He touched them all, wishing he could take everything back home where it belonged, and then chose the smallest of the items – a gold bracelet with an enameled phoenix charm she’d worn every day – and tucked it into the middle of his rucksack with the photo.

Peter surveyed the room a last time. He eyed his baseball and glove and then crossed to the bureau and stuffed them into the rucksack. They didn’t weigh much, and he’d want them when he was back home. Besides, he just felt better when he had them. Then he eased the door open and crept to the kitchen.

He set the rucksack on the oak table, and in the dim light from above the stove, he began to pack supplies. A box of raisins, a sleeve of crackers, and a half-empty jar of peanut butter – Pax would come out of any hiding spot for peanut butter. From the refrigerator, he took a bunch of string cheese sticks and two oranges. He filled the thermos with water and then hunted through drawers until he found matches, which he wrapped in tinfoil. Under the sink he scored two lucky finds: a roll of duct tape and box of heavy-duty garbage bags. A tarp would have been better, but he took two bags with gratitude and zipped the pack.

Finally he took a sheet of paper from the pad beside the phone and began a note: DEAR GRANDFATHER. Peter looked at the words for a minute, as if they were a foreign language, and then crumpled the paper up and started a new note. I LEFT EARLY. WANTED TO GET A GOOD START ON SCHOOL. SEE YOU TONIGHT. He stared at that page for a while, too, wondering if it sounded as guilty as he felt. At last, he added, THANKS FOR EVERYTHING – PETER, placed the note under the saltshaker, and slipped out.

On the brick walk, he shrugged on his sweatshirt and crouched to lace his boots. He straightened up and shouldered his rucksack. Then he took a moment to look around. The house behind him looked smaller than it had when he’d arrived, as if it were already receding into the past. Across the street, clouds scudded along the horizon, and a half-moon suddenly emerged, brightening the road ahead.