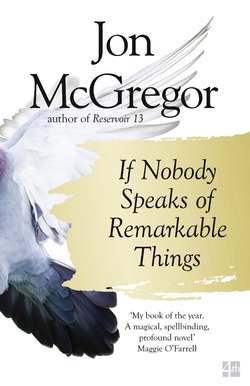

Читать книгу If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things - Jon McGregor - Страница 12

Chapter 7

ОглавлениеWhen I got back from that first appointment it rained for a day and a half.

It woke me up in the middle of the night, a quiet noise at first, burbling across the roof, spattering through the leaves of the trees, and it was good to lie there for a while and listen to it.

But later, when I got up, it was heavier and faster, pouring streaks down the windows, exploding into ricochets on the pavement outside.

I stood by the window watching people in the street struggle with umbrellas.

I phoned work and said I can’t come in I’m sick.

I thought about what my mother would say if she saw me skiving like this, I remembered what she said when I was a child and stuck indoors over rainy weekends.

There’s no use mooching and moping about it she’d say, it’s just the way things are.

Why don’t you play a game she’d say, clapping her hands as if to snap me out of it.

And I’d ask her to point out all the one-player games and she’d tut and leave the room.

I wonder if that’s what she’ll say when I finally tell her, that it’s the way things are, that there’s no use mooching and moping about it.

It doesn’t seem entirely unlikely.

She used to lecture me about it, about taking what you’re given and making the most of it.

Look at me with your dad she’d say, gesturing at him, and I could never tell if she was joking or not.

But it’s how she was, she would always find a plan B if things didn’t go straight, she would always find a way to keep busy.

If it was raining, and she couldn’t hang the washing out, she would kneel over the bath and wring it all through, savagely, until it was dry enough to be folded and put away.

If money was short, which was rare, she would march to the job centre and demand an evening position of quality and standing.

That was what she said, quality and standing, and when they offered her a cleaning job or a shift at the meatpackers she would take it and be grateful.

She always said that, she said you should take it and be grateful.

And so I tried to follow her example that day, hemmed in by the rain, I sat at the table and read all the information they gave me at the clinic.

I tried to take in all the advice in the leaflets, the dietary suggestions, the lifestyle recommendations, the discussions of various options and alternatives.

I read it all very carefully, trying to make sure I understood, making a separate note of the useful telephone numbers.

I even got out a highlighter pen and started marking out sections of particular interest, I thought it was something my mother might approve of.

But it was difficult to absorb much of the information, any of the information, I kept looking through the window and I felt like a sponge left out in the rain, waterlogged, useless.

I was distracted by the pictures, by all these people looking radiant and cheerful, smartly dressed and relaxed.

I knew I didn’t look like that, I knew I didn’t feel relaxed or cheerful.

I didn’t feel able to accept what my body was doing to me, and I still don’t.

It felt like a betrayal, and it still does.

And I kept trying to tell myself to calm down.

To tell myself that this is not something out of the ordinary, this is something that happens.

This is not an unbearable disaster, a thing to be bravely soldiered through.

It’s something that happens.

But I think I need somebody to say these words for me to believe them, I don’t think I can speak clearly or loudly enough when I say them to myself.

One of the leaflets mentioned telling people, who to tell, how long to wait.

I thought about why I haven’t told anyone yet, and what this means.

Perhaps not telling people makes it less real, perhaps it’s not even definite yet, really.

Perhaps I need time to get used to the idea of it, before people’s good intentions start hammering down upon me like rain.

Another of the leaflets had a section on physical effects.

You may find you become tired it said, you may find yourself experiencing dizziness, insomnia, a change in appetite.

There was a list of these things, half a dozen pages of alphabetical discomforts and pains.

I spent a long time thinking about them all, wondering which ones I’d get, wondering how well I would cope.

I thought about backache, nausea, indigestion, faintness and cramps and piles.

I thought about waking in the night with a screaming pain, clutching at the covers with clawed hands.

I thought about banging my fists against my head to distract myself from it.

I thought about religious people who train themselves to walk over burning coals and I wondered if I could control my body in the same way.

I didn’t think I could, and I got scared and gathered all the leaflets up, stacked them away in a kitchen drawer with the scissors and sellotape and elastic bands.

By the middle of the afternoon it had rained so much that the drains were overflowing, clogged up with leaves and newspapers.

The water built up until it was sliding across the road in great sheets, rippled by the wind and parted like a football crowd by passing cars.

I was shocked by the sheer volume of water that came pouring out of the darkness of the sky.

Watching the weight of it crashing into the ground made me feel like a very young child, unable to understand what was really happening.

Like trying to understand radio waves, or imagining computers communicating along glass cables.

I leant my face against the window as the rain piled upon it, streaming down in waves, blurring my vision, making the shops opposite waver and disappear.

There was a time when I might have found this exhilarating, even miraculous, but not that day.

That day it made me nervous and tense, unable to concentrate on anything while the noise of it clattered against the windows and the roof.

I kept opening the door to look for clear skies, and slamming it shut again.

And then around teatime, from nowhere, I smashed all the dirty plates and mugs into the washing-up bowl.

Something swept through me, swept out of and over me, something unstoppable, like water surging from a broken tap and flooding across the kitchen floor.

I don’t quite understand why I felt that way, why I reacted like that.

I wanted to be saying it’s just something that happens.

But I was there, that day, slamming the kitchen door over and over again until the handle came loose.

Smacking my hand against the worktop, kicking the cupboard doors, throwing the plates into the sink.

Going fuckfuckfuck through my clenched teeth.

I wanted someone to see me, I wanted someone to come rushing in, to take hold of me and say hey hey what are you doing, hey come on, what’s wrong.

But there was no one there, and no one came.

I stopped eventually, when I noticed my hands were bleeding.

I must have cut them with the smashed pieces of crockery, picking pieces out of the sink to throw them back in.

I stood still for a few moments, breathing heavily, watching blood drip from my hands onto the broken plates, wanting to sit down but unable to move.

I watched the blood pooling across the palms of my hands.

I looked at the broken plates and mugs.

I wondered where such a fierce rage had come from, and I was scared by the scale of it, by the lack of control I’d had for those few minutes.

I don’t remember ever feeling like that before, and it worried me to think that I might be changing in ways I could do nothing about.

I washed my hands clean, letting the blood and water pour over the broken crockery, counting about a dozen cuts, each as thin as paper.

The water began to sting, so I wrapped my hands in kitchen towel and held them up into the air, leaning back against the worktop, watching the blood soak through.

Later, when the bleeding had stopped and I’d covered my hands in a patchwork of plasters I found in the bathroom, I tried to get myself some food.

I thought it would make me feel better.

I’d been planning to go out and buy something, but I couldn’t face it so I stayed in and ate what I could find.

Peanut butter, sardines, cream crackers, marshmallows.

It gave me a belly-ache, which seemed an appropriate end to a bad day, a wasted and damaged day.

And it kept on raining, rattling endlessly into the ground, piling up in the streets, wedged into the gutters and the drains.

It made the street look squalid and greasy.

People were scurrying along the pavement, their coats tugged tightly around themselves, their heads bowed as though they had something to hide.

And I was locking the door and closing the curtains, and I did have something to hide.