Читать книгу The UK's County Tops - Jonny Muir - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

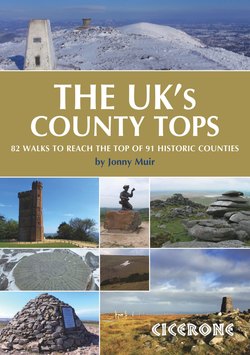

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

It would make a perplexing quiz question. What do the tundra plateau of the Cairngorms, a back garden on the southeast fringe of London and a military firing zone in the Pennines have in common? Answer: they are the locations of three of the UK’s historic ‘county tops’.

No hill list is quite like this one. No other is as diverse or, frankly, as wonderfully ridiculous. The only qualification is being the highest natural ground in a respective county, regardless of obscurity or reputation, be it Inverness-shire’s 1344m Ben Nevis or Huntingdonshire’s 80m Boring Field. In what other list of hills would these two contrary places be happy bedfellows? In between, the roll of county tops includes a wondrous array of high places that thrill the dreams of hillwalkers: Ben Lomond, Cuilcagh, Kinder Scout, Meikle Says Law, Merrick, Pen y Fan and Worcestershire Beacon, to name but a few.

The focus of the 82 routes described here is the so-called historic or traditional counties. These counties hark back to a pre-1974 era when boundaries and names had remained unaltered for more than a century: wonderfully evocative titles such as Westmorland, Cumberland and Brecknockshire. They have shaped the UK’s cultural and geographical identity, and while their boundaries may not be marked on modern maps, they were never formally abolished and so live on.

Perhaps the historic county tops are the country’s finest hill list? Here is the case. They feature in all other ‘bagging’ lists, with Munros, Corbetts, Donalds, Grahams, the Welsh 3000ers, numerous Marilyns and island high points prominent among their ranks. Visit all the county tops and the adventurer will have travelled the length and breadth of the UK, from Cornwall to Shetland, Norfolk to Fermanagh.

They rise in some of the nation’s most splendid landscape, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and National Parks, among them Dartmoor, the Scottish Highlands, the Lake District, the mountains of Mourne and the North Downs. The list also necessarily includes the highest points of the four countries of the UK – Ben Nevis (Scotland), Scafell Pike (England), Slieve Donard (Northern Ireland) and Snowdon (Wales).

Morven, the highest point in Caithness (Route 75)

Leith Hill Tower (Route 6)

The pursuit of the county tops takes the walker into deep glens and valleys, across rolling moorland, past plunging waterfalls and silent lochs, to the roof of soaring summits, along some of the UK’s famous long-distance footpaths, across knife-edge arêtes, through picturesque villages and above startling coastline, not to mention over two live military firing zones.

Some are steeped in history and intrigue. Surrey’s Leith Hill is topped by a 19th-century Gothic tower. Brown Clee Hill in Shropshire is thought to be the scene of more World War II aeroplane crashes than any other UK hill. Ben Macdui, the highest point of both Aberdeenshire and Banffshire, is reputedly haunted by the Grey Man of Macdui. Cairnpapple Hill in West Lothian is the location of a 5500-year-old prehistoric site.

Some are within spitting distance of major cities and towns; others are distant and remote. Some are so easy to attain that a vehicle can be driven right up to the summit; others require arduous, long walks over demanding terrain. It means that for every Dunstable Downs in Bedfordshire (gained by the shortest of walks) there is a Carn Eige in Ross and Cromarty, a day-long expedition over wild territory.

It is this sheer diversity that makes the county tops so appealing: a snapshot of everything that is eccentric and wonderful about walking in the UK. Their conquest will take you into no less than ten of the UK’s National Parks: the Brecon Beacons, the Cairngorms, Dartmoor, Exmoor, the Lake District, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, the Peak District, Northumberland, Pembrokeshire and Snowdonia.

And the best thing about the county tops? There is at least one on everyone’s doorstep. It may be lowly and infrequently walked, or lofty and a honeypot summit, yet the accomplishment, the sense of achievement, is the same. For this is the roof of its respective land, and for a few precious moments the walker is king or queen of that county, lording it above all others, standing the very highest. That is a special feeling.

The historic counties

The historic (or true) counties are the administrative areas that survived for more than a hundred years before sweeping local government changes in the 1970s. They comprise 91 counties (92 if Cromartyshire and Ross-shire are divided). Of the 91, 39 are in England, 33 in Scotland, 13 in Wales and 6 in Northern Ireland. The largest county is Yorkshire and the smallest is Clackmannanshire. Shetland, Suffolk, Cornwall and Fermanagh are the most northerly, easterly, southerly and westerly counties respectively. The lowest county top is Huntingdonshire (Boring Field, 80m) and the highest is Inverness-shire (Ben Nevis, 1344m).

There are now more than 200 administrative areas, counties and unitary authorities in the UK, including the likes of Dudley, Merthyr Tydfil and Southend-on-Sea. It would take a dedicated adventurer to visit the summits of them all, particularly as many are unfortunately low and uninspiring. For example, the list of these high points includes the likes of Liverpool’s Woolton Hill (89m), Melling Mount (36m) in Sefton and, the lowest of them all, East Mount (11m) in Kingston upon Hull. In case you are that dedicated adventurer, a full list is set out in Appendix B.

Defining a county top

A county top is the highest natural (non-man-made) ground within the boundaries or on the border of the county, even if the point of greatest altitude is found on a peak rising in an adjacent county.

Around half a dozen of the county tops, predominately the English ones, have very flat summits, making finding the absolute highest point a Herculean task. A GPS is a useful accompaniment on visits to such places.

More often than not, the highest point is glaringly obvious and will be marked by a cairn, trig pillar or monument. When it is not, such as the tops of Hertfordshire, Oxfordshire and Suffolk, an attempt is made in the route description to identify the exact highest point. Occasionally the location of the summit becomes a purely subjective matter; it is then up to the walker to decide on his or her highest point.

Using this guide

This guide is split into 82 route descriptions, taking the county tops of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland in turn. Six of those routes visit a pair of county tops because they are so close that they can easily be tackled together, while three further routes describe ascents of shared county tops, notably Ben Macdui, the summit of both Aberdeenshire and Banffshire. The Cheviot in Northumberland and Hangingstone Hill in Roxburghshire can also be easily visited in a single walk, but separate routes are given for the sake of preserving national identities.

The cairn straddling the summit of Dunkery Beacon, Somerset (Route 3)

Looking across Antrim from Slieve Gullion (Route 79)

At the beginning of each of the 82 route descriptions the following information is provided: height of the top (or tops) (in metres), location, where to start, map or maps required, difficulty and enjoyment ratings, distance (in kilometres and miles), ascent (in metres) and time required for the entire walk (see ‘Timing’ below). These information boxes are followed by a route description and a map indicating the start/finish point (except in the case of the longest routes which begin with a long walk in where the start/finish is off the map), the advised direction of travel and the location of the county top.

Difficulty

Each walk is given a difficulty rating between zero and five, which is based on a raft of factors, including route-finding, ascent, time, distance and terrain. The ratings are, however, all relative. A moderate walk will become harder in snow or in high winds, for instance. The ratings are simply to give a general impression of what the walker is likely to expect if they embark on any of the walks. Ben Nevis, Ben Macdui, Ben More Assynt and Carn Eige may not be the hardest mountains to climb in the UK, but they are certainly among the hardest to climb in this book, hence they are rated as five for difficulty.

Short-distance walks or ones involving a small amount of ascent are rated as zero or one. Longer walks requiring navigation skills and over rougher ground score two or three. Walks that are longer still (in distance and time), traverse complicated landscape, involve many hundreds of metres of height gain and loss, and are in locations where weather conditions can change rapidly, are rated as four or five.

Enjoyment

Ratings between zero and five are also given for enjoyment. Do not infer that a county top with a zero or one score means it is an awful place that is hardly worth visiting. It simply indicates that it is not as exciting as Helvellyn or Snowdon. Generally speaking, enjoyment and excitement levels go up the higher one ascends, but that is not always the case. Hills such as Holyhead Mountain on Anglesey, Leith Hill in Surrey and Worcestershire Beacon are fantastically rewarding places to visit, despite their relatively low altitude.

Enjoyment is, of course, hugely subjective. Climbing Ben Nevis can be a joy. There can be no greater feeling than standing on our nation’s summit. But a clag-shrouded, wind-buffeted Ben Nevis is a different proposition. Enjoyment levels begin to plummet and enthusiasm starts to flag. Weather, as always in the UK, is a great determinate of mood.

Timing

A frequent complaint about guidebooks is that the author has under- or overestimated times for walks. It is hard not to make a similar error. Wide time margins have therefore been provided in some cases, giving the shortest time for quick and experienced walkers and the longest time for those who prefer a slower pace. If anything the timings in this guide may be on the fast side. After you have followed a couple of the routes, however, you should be able to gauge where you fit into the ranges given and estimate your likely time accordingly.

Ascent

The total ascent – given in metres – includes not just the cumulative height climbed from start to summit, but also any encountered during the descent. Again, like timing, the amount of ascent may differ if slightly alternative routes are inadvertently followed.

When to go

The UK’s temperate climate means its hills and mountains are accessible year-round, although the highest Scottish mountains, Snowdonia, the Lake District peaks and the Pennines are likely to be snow-covered for long periods during the winter months. There are access restrictions on two of the county tops – High Willhays in Devon and Mickle Fell in Yorkshire – because both rise on Ministry of Defence land. Great Rhos in Radnorshire also lies close to a military ammunition testing area. Further details on access to these hills are given in the respective sections for each county top.

The best-known and most popular county tops – Ben Lomond, Ben Nevis, Dunkery Beacon, Helvellyn, Scafell Pike and Snowdon – can be tremendously busy during periods of fine and settled weather, especially during school holidays and the summer months. Ben Nevis is notoriously congested, with an estimated 160,000 people – a quarter of them charity walkers – scaling the mountain every year, the vast majority by the same path. To avoid the crowds on Ben Nevis and the other busiest county tops, begin an ascent early in the morning or go out of season.

Getting there

Unfortunately, public transport is not geared around the UK’s hills and mountains. Buses and trains will only get the walker so far. It may not be the most eco-friendly way, but a car is usually the easiest and quickest option and advice on where to park is given in the information box at the start of each route description. Mountain bikes can be used to speed ascents, particularly on long walks such as Ben Macdui and Morven. To get to Arran and Hoy (on Orkney), ferries must be called upon, departing from Ardrossan in Ayrshire and Stromness on Orkney’s Mainland respectively. Air and sea services operate between the Scottish mainland and Orkney and Shetland.

Safety in the hills

The UK’s hills and mountains can be challenging and daunting places, claiming dozens of lives each year. In 2009, mountain rescue teams in England and Wales dealt with 37 fatalities, while a further 667 people were injured. The number of reported incidents has increased year-on-year since 2004, rising from 609 to 1054 – close to three a day – in 2009. Falls and trips represent almost half of all mountain incidents, while many other call outs were prompted by walkers who were overdue or lost. Meanwhile, mountain rescue teams in Scotland reported 20 deaths and 60 serious injuries in 2008. Of the fatalities, seven occurred in summer walking conditions and six in winter. The busiest group was Lochaber, the team with responsibility for Ben Nevis. The two mountain rescue teams operating in Northern Ireland – Mourne and North West – were called to 54 incidents in 2008. Across Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, teams dealt with 13 deaths (although four were the occupants of a light aircraft) during the year. More than half of the 214 incidents happened at weekends, with Sunday being busier than Saturday.

Rime-coated toposcope on Ben Macdui (Route 68)

Heavy winter snowfall in 2009 and 2010 also greatly heightened the risk of avalanches, particularly in Scotland. Three climbers died in an avalanche on Buachaille Etive Mor, a Glencoe Munro, in January 2009, in what was one of the worst disasters in the Scottish mountains for decades. Up-to-date information on avalanche risk in Scotland is available at www.sais.gov.uk.

The ridge walks described in this guide, notably the Carn Mor Dearg Arête close to Ben Nevis or Striding Edge on Helvellyn, are potentially dangerous, and care should clearly be taken. Away from the obvious challenges of navigation, terrain and the gradient of a slope, an ever-present variable factor is the weather. Weather in the UK, particularly in Scotland, is notoriously changeable; Scots are not joking when they refer to ‘four seasons in one day’. Even in summer, the weather on the highest county tops can be extreme: high winds, thick mist and sometimes snow.

10 top tips for mountain safety

Always go equipped with a compass and map (and GPS if you can) – and know how to use them.

Plan your route in advance.

For the more challenging tops, work out an escape route should conditions deteriorate unexpectedly.

Always wear appropriate, comfortable footwear and carry waterproofs.

Always check mountain weather forecasts.

Know your own fitness levels.

Prepare for the temperature to be several degrees lower at the top of the hill than at the foot, and take the potential wind-chill factor into account.

Never be afraid to turn back or reduce expectations.

Make sure you tell somewhere what you plan to do, and tell them when you return.

And never forget: the hill will still be there tomorrow.

Merrick and Loch Valley from the Rig of the Jarkness (Route 56) (photo: Ronald Turnbull)

ALAN HINKES AND THE COUNTY TOPS

What does a man do once he has conquered the world’s 8000m mountains? He climbs England’s county tops, of course. Alan Hinkes, the first Briton to scale the 14 highest peaks on the planet, took up the challenge in 2010 to raise money for mountain rescue teams. Starting on The Cheviot and finishing on Helvellyn, Hinkes visited 39 county tops in just eight days. The summits chosen by Hinkes were predominately the historic county tops. There were three exceptions, however: in Oxfordshire he scaled Whitehorse Hill rather than Bald Hill; in Warwickshire he swapped Ebrington Hill for Turner’s Hill; in Cheshire he replaced Black Hill for Shining Tor. Reflecting on his marathon effort, Hinkes said: ‘The British mountains are not insignificant and I love to be out there, especially in Yorkshire and the Lakes. Other places might fascinate me at first impact but after being there a while I realise my heart is in the British hills.’