Читать книгу Cruising Utopia, 10th Anniversary Edition - José Esteban Muñoz - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Before and After

By Joshua Chambers-Letson, Tavia Nyong’o, and Ann Pellegrini

One may not cast a picture of utopia in a positive manner. Every attempt to describe or portray utopia in a simple way, i.e., it will be like this, would be an attempt to avoid the antinomy of death and to speak about the elimination of death as if death did not exist. That is perhaps the most profound reason, the metaphysical reason, why one can actually talk about utopia only in a negative way …

—Theodor Adorno, in conversation with Ernst Bloch1

TO THINK, WRITE, dream, and live in the wake of heartbreak: this is the challenge posed by “Hope in the Face of Heartbreak,” the short essay that is published for the first time in this new edition of Cruising Utopia. It is also the charge we are faced with here: how to think and write after José Muñoz—and also for him—in the painful, temporally out of joint forever “after” of this foreword.

“Hope in the Face of Heartbreak” was written to be heard and was given as a talk, in September 2013, at the University of Toronto to celebrate the launch of the Women & Gender Studies Institute’s PhD Program. The manuscript bears the traces of the live occasion; it also carries the literal traces of the one who wrote and spoke its words aloud. “Hope’s biggest obstacle is failure,” the manuscript begins, its opening words neatly typed and printed. But, midway through the opening paragraph, the typeface is interrupted by hand-writing. The pivot by hand, to handed-ness, happens at a critical juncture where Muñoz is reminding his audience of a distinction made by Ernst Bloch (key interlocutor of Cruising Utopia), between abstract and concrete or educated hope:

In part we must take on a kind of abstract hope [that] is not much more than merely wishing and instead we need to participate in a more concrete hope, what Ernst Bloch would call an educated hope, the kind that is grounded and consequential, a mode of hoping that is cognizant of exactly what obstacles present themselves in the face of this hoping.

The words “this hoping” are crossed out. The revised sentence reads “… a mode of hoping that is cognizant of exactly what obstacles present themselves in the face of obstacles that so often feel insurmountable.” So, if the original sentence repeated the word “hoping,” the revised one doubles down on the “obstacles.” On the manuscript, we can glimpse the handwritten word “our,” also crossed out, before he settles on the word “obstacles.” Hope falters, gives way to more obstacles.

“Hope in the Face of Heartbreak” is revisiting and also expanding on arguments made in Cruising Utopia. At this early moment in the talk, it’s as if Muñoz needs to stress the “obstacles” as a wedge against overly hopeful or romanticizing readings of Cruising Utopia. In our conversations with our late friend and comrade, he occasionally expressed disappointment that his defense of utopia was enthusiastically read by some as uncritical optimism. His work testifies to the contrary. Hope is work; we are disappointed; what’s more, we repeatedly disappoint each other. But the crossing out of “this hoping” is neither the cancellation of grounds for hope, nor a discharge of the responsibility to work to change present reality. It is rather a call to describe the obstacle without being undone by that very effort.

A sentence later, still in the hand-written addition, there is another crossing out; obstacle is not a hard stop, it is a challenge: “… I have chosen to focus on two texts, one scholarly [Robyn Wiegman’s Object Lessons] and one cultural [Anna Margarita Albelo’s film Who’s Afraid of Vagina Wolf?], that offer snapshots at of some of the obstacle challenge[s] we need to not only survive but surpass to achieve hope in the face of an often heart breaking reality.” The first page of the short manuscript ends with these hand-written words: “in the face of an often heart breaking reality.” We who survive are left to face this challenge without him. We are also charged by him to do so.

A common sight during his lifetime: Before giving a paper, he’s sitting on a panel, hunched over, crunching on ice, and listening intently to the person speaking. Multi-tasking, he simultaneously flips through the pages he’s set on the table in front of him, and takes his pen and scribbles something across the page: a revision in the text. Back to listening, pulling his right foot across his left knee, a glance out over the room to see who is there, before glancing down at another page and posing the pen for another revision.

One can only imagine what revisions he might have made for this edition of Cruising Utopia. The challenge we faced in writing this foreword is that a foreword or introduction assumes an anterior stance, with the authors and readers positioned before the text. But as we stand in the author’s stead, introducing the text by meditating on revisions that Muñoz cannot make, we do so because we introduce him in the time after his death.

If we have never been queer, as Muñoz famously asserts throughout the text, then there is a degree to which we are always standing before queer loss. This is the nature of queer grief. It is informed by life lived after the historical accumulation of queer deaths: a collection of losses that have taught us to know (because our survival depends upon this knowledge) that we are also standing before losses that have yet to come.

Queer grief is characterized by the simultaneity of grieving those we have loved and lost, alongside mourning for a queerness and the forms of queer life that we have not yet known and are still yet to lose. Lingering on Muñoz’s handwritten notes and imagining the types of revisions he might have made is a way of inhabiting the incommensurable simultaneity of before and after. It is to perform within the reparative matrix of queer temporality proposed by Muñoz’s teacher, Eve Sedgwick: “Because the [reparative] reader has room to realize that the future may be different from the present, it is also possible for her to entertain such profoundly painful, profoundly relieving, ethically crucial possibilities as that the past, in turn, could have happened differently from the way it actually did.”2 Throughout Cruising Utopia, Muñoz mines the past for glimmers of utopian potential that are rich with the possibility of a past that “could have happened differently from the way that it actually did.” He invites us to put these glimmers to work, both as we cast a negative or critical picture of the insufficiencies of the present, but also as we undertake the work of hoping for, rehearsing, dreaming, and charting news paths toward different and queerer futures.

Alexandra T. Vazquez, Muñoz’s student, writes that “our teachers leave behind care instructions for any and all kinds of arrivals and departures.”3 The students of Cruising Utopia (past, present, and future) might thus approach the text as an instruction manual for how to have hope both before and after the death of the teacher. To read the text in the time after Muñoz’s death is to be reminded, once more, that queer of color life occurs within this out-of-joint temporality such that queer of color death is not a negating after to Cruising Utopia. Rather, the negation that is queer death presupposes the text’s entire critical enterprise (and was crucial to the opening of his first book, Disidentifications, with its extended critical account of racial melancholia).4 To approach the text from this vantage is to be confronted with the question that animates Muñoz’s address: How are we to have hope while living simultaneously in the before and after of queer heartbreak? The answer, far from veering away from the discourse of negation, requires a counter-intuitive turn toward the negative. For utopia, though it bears many positive qualities, also bears negation, as originating from the Greek for “no place” or “not place.” Utopia is not the antithesis of negation in this sense, so much as it is a critical means of working with and through negation. Queer utopia is the impossible performance of the negation of the negation.

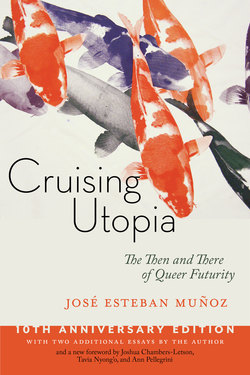

Since its publication ten years ago, Cruising Utopia has had a wide impact across and beyond a range of academic fields. Appearing at the height of the controversy regarding the anti-relational thesis in queer studies, the book invited the field to turn the page on a somewhat stalled debate by rearticulating the critical negativity associated with anti-relationality in a new way. Without acceding to the assimilationist vision of queer futures that underpinned homonormativity, it performed a negative dialectic that nevertheless expressed a politics of hope: “Here the negative becomes the resource for a certain mode of queer utopianism.”5 The audacious opening move of the book, to declare that we are “not yet” queer, drew on the critical utopianism of the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch as much as it was in dialogue with a still-expanding literature on queer temporality, whose interlocutors included Sedgwick, Carolyn Dinshaw, Jack Halberstam, and Elizabeth Freeman.6

Throughout Cruising Utopia, Muñoz presumes and builds upon the queer of color critique pioneered in his first book, Disidentifications. And, as with Disidentifications, a key reason for Cruising Utopia’s wide influence has been its astounding archive. The book moves promiscuously and enthusiastically across its sources in order to braid together the “no-longer-conscious” of queer world-making with the “not-yet-here” of critical utopianism. No doubt, the richly described worlds of the text stand in some tension with the tradition of negative utopianism he draws upon. For Bloch, and especially his interlocutor Adorno, utopian thought is first and foremost a negation; Bloch even characterizes the hope that inspirits utopian thinking as “the determined negation of that which continually makes the opposite of the hoped-for object possible.”7 It is through drawing out this almost apophatic concept of hope and of utopia that Muñoz is able ingeniously to reframe queer cruising. As one alert reviewer of the first edition noticed, cruising is a way of moving with “no specific destination”; the ultimate goal is “to get lost [ … ] in webs of relationality and queer sociality.”8 Cruising, that is to say, is as much the method of the book as is critical utopianism.

After Muñoz’s death, his friend and colleague Barbara Browning issued a call for people to inscribe the following passage from the book’s opening paragraph in a paradigmatic location of queer cruising, the bathroom stall: “Some will say that all we have are the pleasures of this moment, but we must never settle for that minimal transport; we must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the word, and ultimately new worlds.”9 People sporadically performed the act in bathrooms or other public spaces (including a bathroom in the department where Muñoz taught), sometimes posting a photo of the transgression (or of the encounter with its written trace) to social media. It circulated in other ways as well: a group of queer activists designed and distributed stickers with the passage printed across Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds (an installation of balloons discussed in the book’s eighth chapter). And in a statement to the Windy City Times discussing her gender transition, the film director Lilly Wachowski wrote: “I have a quote in my office … by José Muñoz given to me by a good friend. I stare at it in contemplation sometimes trying to decipher its meaning but the last sentence resonates: ‘Queerness is essentially about the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality for another world.’”10

The popularity and circulation of this sentiment—which pits futurity against the present—is reflective of the general reception of Cruising Utopia since its publication, which draws upon and emphasizes the text’s positive elaborations on queerness, hope, and futurity by positioning them against the (negating) poverty of the present. As Muñoz insists throughout the book, “The present is not enough. It is impoverished and toxic for queers and other people who do not feel the privilege of majoritarian belonging, normative tastes, and ‘rational’ expectations.”11 But along these very lines, an overemphasis on futurity, a flat rejection of the present, and an over-romanticization of the past risk eliding Muñoz’s nuanced insistence on the political (if not revolutionary) dimension of a queer utopian imaginary as a negative dialectic.

Muñoz warned us against disappearing wholly into futurity since “one cannot afford” to simply “turn away from the present.” The present demands our ethical consideration and the task at hand is not to refuse the present altogether, but rather to maneuver from the present’s vantage point at the crossroads of life that is lived after catastrophe (as may be the case with queer, black, and brown life) and simultaneously before it. The utopian impulse yields the idealist power of the utopian imaginary to offer a negative critique of the present and past (framing the insufficiencies of both) while opening up different avenues through which we might construct alternative possibilities for queerness’s future beyond the limited options that are presently before us. That we are standing before the possibility, even likelihood, of hope’s disappointment does not so much negate the principle of hope as confirm it.

Throughout Cruising Utopia, Muñoz insists that “hope and disappointment operate within a dialectical tension in this notion of queer utopia.”12 The utopian imaginary is understood to be an act of failure in the face of a stultifying regime of pragmatism and normativity: “Utopia’s rejection of pragmatism is often associated with failure. And … utopianism represents a failure to be normal.”13 Queerness, blackness, brownness, minoritarian becoming, and the utopian imaginary thus resonate with each other as they all cohere around a certain “failure to be normal,” unwilling or unable to submit to the pragmatic dictates of majoritarian being. This failure, which is situated both after and before defeat does not counter-intuitively confirm the totality of defeat, however, so much as it opens up queer avenues for other potentials to flicker in (and out) of being.

Bloch described hope’s failure as the ontological grounds on which hope is defined: “It too can be, and will be, disappointed; indeed, it must be so, as a matter of honor, or else it would not be hope.” That hope will be disappointed, and fail us, is not its negation but its condition of possibility. When the acute failures and dangers of the present (of “normal”, “straight,” “white,” or “capitalist” time) threaten us, we turn to the utopian imaginary in order to activate queer and minoritarian ways of being in the world and being-together. We do so to survive the shattering experience of living within an impossible present, while charting the course for a new and different future.

The frequent and even necessary disappointment of hope is due to an incommensurability: things do not line up; loved objects (whether persons, theories, or social movements) let us down. Theories about identities and politics frequently miss actually existing subjects in their complexity, messiness, and plurality. To paraphrase Muñoz’s powerful concluding paragraph in “Hope in the Face of Heartbreak,” however, this missed encounter, this incommensurability, far from disqualifying queer of color critique or cultural production, is instead the very condition—however blasted and painful it can sometimes feel—of our being-with others. Hope may not be commensurate to reality; our hopeful actions may not produce—may not ever produce once and for all—the hoped-for end. But this prizing of the incommensurate over the equivalent is a queer angle of vision, a queer ethics for living through the gaps between what we need and what we get, what we allow ourselves to want and what we can survive and transform in the now.

The value and the challenge of the incommensurable are the focus of another essay published in this expanded edition of Cruising Utopia, “Race, Sex, and the Incommensurate: Gary Fisher with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.” In this essay, too, we can see Muñoz clarifying arguments he first made in Cruising Utopia. The focus of this essay, which was first published in Queer Futures: Reconsidering Ethics, Activism, and the Political, edited by Elahe Haschemi Yekani, Eveline Kilian, and Beatrice Michaelis, proleptically figures this foreword: Muñoz is writing about the collaboration between Fisher and Sedgwick. Fisher, like Muñoz, was one of Sedgwick’s graduate students (Fisher at Berkeley, Muñoz at Duke). When Fisher died in 1994, too young and “ahead of his time,” as the saying goes, Sedgwick took on the task of editing and publishing a collection of his short stories and poems, Gary in Your Pocket (1996). Muñoz is interested in the difficult reception of this text, and what it can tell us about “a kind of queer politics of the incommensurable”—an incommensurability characterized by differential power dynamics (advisor and student), race (Fisher’s blackness and Sedgwick’s whiteness), and gender. But he is equally referring to Fisher’s and Sedgwick’s collaboration and a communism begun in life, continued after the death of one of them, living on in their readers—known, anticipated, never imagined—after the death of all.

This mode of communism was anticipatory, but also material. Muñoz understood it as manifest, or performed, within the lived experiences of queers of color and in the brown commons. In “Race, Sex, and the Incommensurate,” he illustrates this mode of communism (as he did in Cruising Utopia) through stories about relationships between incommensurably different types of beings (here, Sedgwick and Fisher) as well as the aesthetic example (Fisher’s short story “Arabesque”). This commons was an experience of, in Muñoz’s words, “a dynamic that partially transpires under the sign of ‘queer of color,’ that is routinely misread by the lens of a politics of equivalence, but that becomes newly accessible as a sharing (out) of a nonequivalent, incommensurable, and incalculable sense of queerness.” This theorization of the queer of color commons anticipates the turn in his final works toward describing a brown commons. There, he was attending to the way certain racialized people (primarily Latinx, but not solely) are made to be brown through “global and local forces [that] constantly attempt to degrade their value and diminish their verve. But they are also brown insofar as they smolder with a life and persistence; they are brown because brown is a common color shared by a commons that is of and for the multitude.”14 This brown commons, like the mode of queer of color communism depicted in the essay on Sedgwick and Fisher, is “an example of collectivity with and through the incommensurable.”

As editors, we find ourselves incommensurate to the task of completing his work, even as we recognize that this form of adjacency was precisely what he sought to theorize in some of his very last writings on the concept of being singular plural. Some interpret this concept as a pretty but vague synonym for something like “community,” but community was a normative, even hegemonic term, of which Muñoz remained consistently skeptical. More than any actually existing collectivity in the here and now, his reconsideration of the ethics of Sedgwick’s being with Fisher leads to a proposal that we think of queer relationality as incommensurate with itself. His work, and our work on his work, point us to a spacing out in time—futures, pasts, and presents—in which we may not yet be queer, but can nonetheless orient ourselves to queerness’s horizon.