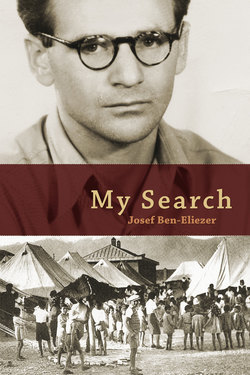

Читать книгу My Search - Josef Ben-Eliezer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

Rozwadów: Life in the Shtetl

ROZWADÓW WAS A SMALL TOWN, maybe around five thousand people. In the middle of town was a square – huge, in my memory – where a market was held once a week. A busy road went right through the square. Very occasionally we saw an automobile go through, but the main bustle was the constant traffic of horses and wagons. I had a good friend, a man who delivered goods for my father. He had fled the Communists in his native Georgia and was quite poor. I loved to spend time with him and with his family. It was fascinating to watch him as he made ropes. He also told wonderful stories in his unique Yiddish dialect.

We lived in a terraced house along one side of the square. At the back of the house was a yard stretching one to two hundred meters out to a dirt road. We shared a well with our neighbor. A wood stove heated the house. There was no running water, and we had an outdoor toilet. It all sounds quite primitive now, but at the time it was normal; everyone lived like that.

My father ran a wholesale business in sugar and other commodities. He bought in big quantities and supplied shops in a large area around Rozwadów. The goods were stored in the ground floor and cellar rooms of our house. We lived in the upstairs rooms. I often listened to him discussing business with my mother. They didn’t think I understood it, but I was very curious and took it all in. The problem was always cash flow. People bought things on credit and then couldn’t pay. It was a constant worry for my parents.

Occasionally, my father also had stores of candy. At such times I was frequently in the shop at the front of the house asking for some, or begging for money to buy some from another shop down the road. I was a finicky eater, and my parents would sometimes pay me for eating my meals. Father was fairly strict with money, but after Alte Chaiya, my grandmother, came to live with us, I usually got what I wanted. She had first stayed on in Germany, but as we began to hear more and more about what was happening in Germany, my mother finally convinced her to come and live with us.

Alte Chaiya’s death was a real blow to our family, although she was well over eighty. She was frying eggs one morning for Leo’s breakfast. Suddenly she called our mother over and told her it was time for her to go. Mother couldn’t believe she was serious; she hadn’t been sick or anything. But Alte Chaiya simply lay down on her bed and peacefully passed away.

Rozwadów was probably half Jewish and half Catholic, and we lived in a mixed neighborhood. The butcher’s shop two or three houses away from us usually had pork hanging in the window. One of our close neighbors was Polish, but we had very little contact with them.

There was a strong feeling of community among the Jewish townspeople, in spite of all the differences between rich and poor; in spite of gossip, intrigue, and all kinds of similar things. Jews did not have full rights in Poland, but we were not restricted in our contacts with Poles. I’m sure my parents dealt often with Poles in their business, but as a child I didn’t have any contact. In fact, I only learned Polish when I started school. We avoided the Catholic Church, where we heard that they worshipped idols. And we were always afraid of the Christians, especially at Easter. After their church services, they would often go out on pogroms, vandalizing property and trying to break into our shops. So at Easter time, or any of the Christian holidays, we would lock up our shops.

Very soon after we arrived in Rozwadów, my father said to me, “Well, Josef, you have to go to chaider.” This was the traditional school for Jewish boys. There we learned Hebrew, starting with the alphabet. The melamet (teacher) led us in chanting the letters together in a sing-song voice, and he was not afraid to use the stick to keep order. Later, we learned parts of the Pentateuch by repeating after him. We must have learned something there, because I picked up Hebrew quickly when I later arrived in Israel.

We boys were quite a handful for our teacher. The boys had found out that if they formed a line and one touched the live wire in the circuit box, the last boy in the line felt the shock. So that shock was my rude introduction to chaider as a four-year-old. If the teacher left the room, bedlam broke out among the fifteen to twenty boys. Even if he was there, some risked beatings to play cards under the table. I remember one older boy who collected money from the other boys by selling each one a tree in Palestine. I never saw my tree, but I certainly learned a few business tricks from him!

When I was seven, I had to go to Polish school, so my parents and my brother and sister taught me to answer a few simple questions: what my name was, where I was born, the name of my father and mother and that kind of thing. In time, I learned the basics of the Polish language and I was quite good in math, but I have no happy memories of that school. Quite apart from the language difficulties, the Polish children, and even the teacher, looked down on the Jewish pupils and generally made our lives miserable.

We didn’t often gather as a family for a meal. Mother or Lena would just run up from the shop and cook something for the children. In the evenings, it was a little more gathered. On Sundays, we had to close the shop, so we often went on excursions. Businessmen would go to the river. On Saturdays Jewish people did no business and we did not walk long distances, but on Sundays and general holidays we took the chance to do this kind of thing. I remember happy family excursions by the San River, and picnics.

I was quite a nervous child with many health problems and I didn’t eat properly. I often went to the dentist – probably because of my incorrigible sweet tooth. When I was about five, I had some kind of growth on my toe. Someone told my mother about a man who could help; I don’t think he was a proper doctor. He put some powder on the growth and I let out a blood-curdling scream that still rings in my ears. The growth never came back, but I’ve had a scar from that treatment ever since.

Once I had to spend several weeks in Kraków, where a specialist treated my infected ear. I have terrible memories of how he scraped the pus out of my ear each day. But when we came home, my parents bought me a tricycle. This was quite a novelty in Rozwadów.

When I was about nine, my mother took Judith and me to the Carpathian Mountains for several weeks’ vacation. I still have a photo of us standing with a man in a bear costume hugging us. I think this excursion was an effort to improve my health.

We had not actually planned to stay in Rozwadów; my parents still wanted to go to Palestine. Uncle Chaim Simcha and his two boys were already there – I guess they had slipped through before the British tried to stop the influx of German refugees. Father often told exciting stories about what he had experienced in the eight months he was there. He made it sound very interesting and glamorous, so I dreamed of one day going to Palestine, the Promised Land.

Leo and friend, Josef and friend outside

their house in Rozwadów

Josef and Judith at the circus