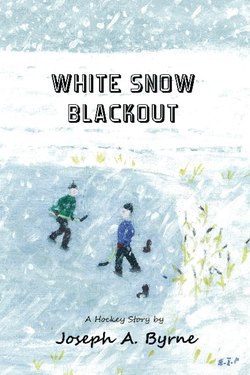

Читать книгу White Snow Blackout - Joseph A. Byrne - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 THE DAY I MADE THE BIG TIME

ОглавлениеI kept working at hockey that winter. I turned seven the next year in late November. I would shoot a puck in the barn after school every day, after the cattle were fed. I couldn’t shoot raisers yet, but once in a while, if the puck hit something like dried manure, or dirt, it would bounce into the air. There was no pattern to my shooting. I didn’t practice technique, because I didn’t know any. I didn’t know it mattered either. I was pretty good with a pitch fork by that age and with a shovel. I guessed that shooting pucks was the same thing as handling a fork or a shovel.

It was to some extent. By the end of winter, I could shoot the odd raiser. One time, I even raised the puck with a backhander. I didn’t know about slap shots, so I didn’t practice those.

Then one day, it happened. I pushed against the puck, with my Sunoco stick. I pushed hard against it. The stick broke. The blade flew waist high, all the way to the back wall at the end of the barn. The puck made it about half way. I was very happy I had shot the puck so hard, it broke my stick. After that, I used a tobacco lath to shoot pucks and sometimes a push broom. I held it sideways or shot backhanders with it. I thought I was getting pretty good, especially with the tobacco laths, except that I broke a lot of them. I liked the laths though. They had some spring to them. The puck seemed to sling-shot off of them.

But that wasn’t the big time. It happened this way. The big guys and some of the girls from Grades 6, 7 and 8, decided to make a skating rink.

“We need a real rink here at school,” they said, “with boards and everything.”

Jim and I were in Grade 2 then. We were a couple of farm kids, used to work. We were pretty good at cutting out snow chunks and carrying them over to the others who were building the boards for the rink, using the snow blocks we carried to them. Their plan was to flood the asphalt square that had just been put in at our school, Sacred Heart, or Old Number 2, as we called it.

It was a great plan. We worked at it for more than a week. The snow boards were built head high. One of the guys, I think she was a girl, suggested that if they wet the inside of the snow with water each night, it would make the boards hard, with an ice shell on them.

I had never played hockey with Grade 7 and 8’s before. I did have one big game against Jim and his hockey buddy, Randy. It was a game of two-on-two. Norman was my team mate. Norman was a tough, wiry farm kid like me, only bigger. Randy was a smoothie. He could skate real circles, turn both left and right with the puck, skate backwards. He was amazing. Randy also laughed and talked as he was doing it. One time during the game, he skated toward us with the puck.

“Now you see it,” he said as he pushed the puck toward me. I swatted at it. “Now you don’t,” he laughed as he pulled the puck back over with the toe of his stick, and pulled it around me, depositing it into the empty net.

The nets were actually made with a pair of farm boots acting as goal posts at each end. They made really good nets because if you did shoot a raiser, they could bounce off the top of the boot and into the net or bounce wide of it.

Jim seemed to be able to do whatever he wanted. He would skate through us, pass the puck back to Randy, play keep-away with it and generally have fun. But there was one significant aspect about his horseplay with us. He did all of this before he scored his first goal, but not after. After he scored the first goal, he played net. Sometimes, he would just stand there and stickhandle it by and through us, right there in the crease. He would pull the puck to his skates, kick it back and pull it back and through his legs. We would work hard in the crease trying to get the puck, from our second grade superstar, he pulling it through our legs with ease, back and forth, like a magician. He would sometimes lift the puck up into the air, to send Randy on a breakaway, on the empty net. Randy would go at it slow sometimes, letting us catch up, maybe circle us a couple of times, before depositing the puck in the net.

We won that game 10 to 9. Norman and I worked furiously. Jim played goal and Randy had good practice. We were his pylons, except that we were better than pylons because we could move—a little bit anyway.

The big day came. The big guys announced that the ice was frozen. They asked everyone to bring their skates, including the girls, but not the Grade 2’s.

“No one under Grade 7 can play,” they said, except for Tom and Don. They were in Grade 6, I think, “and Jim, of course. Jim can play,” they said, “because he is better than us,” someone joked, but no one laughed in case it was true.

“We’re going to play real hockey,” they said, “and we can’t have any ankle benders on the ice. We don’t want any babies on the ice, either,” they added, and laughed.

Jim looked at them and put his arm around my shoulders. He stood about a foot taller than me.

“No way!” Jim said. “Joe helped us build this rink. He helped us every day. If Joe can’t play, I’m not playing either.”

I was nervous and amazed at how he stood up to them for me. They were his friends after all. They spoke about him in superlatives. I expected them to say, “He can’t even skate.” Instead, to my surprise, they said, “Okay, Jim, you’re right. Joe can play too.” I had made the big time.

The next day, I thought about asking my mother to tie my skates before I got on the bus to go to school. I asked her, but she ignored me, so I picked them up the wrong way, not knowing to hold them by the laces, clashed the blades together and went out to wait for the bus. It didn’t matter if I clashed them together. I could look as good as Team Canada was looking now, against the Russians, them swirling around us. Besides, clashing the blades together wouldn’t hurt my skates. They had never been sharpened. They were dull as dull can be anyway.

That day, at noon hour, I did the best I could to tie the skates tightly. I pulled at the laces as hard as I could and then secured them with two first shoe knots. I thought they would hold tight.

Jim scored a few goals against the big guys. I wasn’t in the play much, usually trailing it by a considerable distance, both ways down the ice. But they said I made a few good plays. Every time I got the puck, I gave it to Jim right away or tried to. That was always a good play. On one goal, one of the big guys said I got an assist. I didn’t know what that meant, but he rubbed his hockey glove over my head, knocking my hat to the ice. I picked it up. “Good play,” he said. I think he said that part to Jim, but I’m not sure.