Читать книгу Making Beats - Joseph G. Schloss - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter 1

Introduction

Joe: I wanted to get you to tell that story about when you were talking to your mother-in-law about painting….

Mr. Supreme: Oh yeah, and we were arguing, ’cause she was saying I didn’t make music. That it’s not art…. She really didn’t understand at all, and we argued for about two hours about it. Basically, at the end she said … if I took the sounds, it’s not mine—that I took it from someone.

And then I explained to her: What’s the difference if I take a snare drum off of a record, or I take a snare drum and slap it with a drum stick? OK, the difference is gonna be the sound. Because when it was recorded, it was maybe a different snare, or had a reverb effect, or the mic was placed funny. It’s a different sound. But what’s the difference between taking the sound from the record or a drum? It’s the sound that you’re using, and then you create something. You make a whole new song with it.

And she paints, so I told her, “You don’t actually make the paint.” You know what I’m saying? “You’re not painting, ’cause you don’t make the paint.” … But that’s what it is; it’s like painting a picture. (Mr. Supreme 1998a)

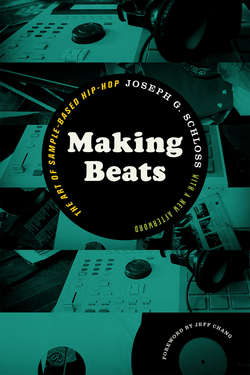

Some people make beats. They use digital technology to take sounds from old records and organize them into new patterns, into hip-hop. They do it for fun and money and because their friends think it’s cool. They do it because they find it artistically and personally fulfilling. They do it because they can’t rap. They do it to show off their record collections. Sometimes they don’t know why they do it; they just do. This book is about those people and their many reasons.

Beats—musical collages composed of brief segments of recorded sound—are one of two relatively discrete endeavors that come together to form the musical element of hip-hop culture; the other element is rhymes (rhythmic poetry). This division of labor derives from the earliest hip-hop music, which consisted of live performances in which a deejay played the most rhythmic sections of popular records accompanied by a master of ceremonies—an MC—who exhorted the crowd to dance, shared local information, and noted his or her own skill on the microphone. When hip-hop expanded to recorded contexts, both of these roles became somewhat more complex. MCs began to create increasingly involved narratives using complex rhythms and cadences. And although deejays continued to make music with turntables when performing live, most also developed other strategies for use in the studio, and these eventually came to include the use of digital sampling. As these studio methodologies gained popularity, the deejays who used them became known as producers.1

Today, hip-hop is a diverse and vibrant culture that makes use of a variety of techniques and approaches to serve many communities throughout the United States and, in fact, the world. There remains, however, a surprisingly close bond among producers regardless of geographical or social distance. They see themselves as a breed apart, bearers of a frequently overlooked and often maligned tradition. This book is about these hip-hop producers, their community, their values and their imagination.

I have relied heavily on ethnographic methods such as participant observation to study these questions. As a result, the picture that emerges in this study expresses a rather different perspective from that of other studies of hip-hop or popular music in general. It does no disservice to previous work to say that it has tended to focus on certain areas (such as the influence of the cultural logic of late capitalism on urban identities, the representation of race in popular culture, etc.) to the exclusion of others (such as the specific aesthetic goals that artists have articulated). Nor is it a criticism to say that this is largely a result of its methodologies, which have, for the most part, been drawn from literary analysis. We must simply note that there are blank spaces and then set about to filling them in. Ethnography, I believe, is a good place to start.

Due to the approaches I have employed, common issues of poststructuralist anthropology—such as the social construction of “the field,” the effect of the power relationships that exist between a researcher and his or her subjects, and the subjectivities of academic writing—have exerted a decisive influence on the way my study is framed. Conveniently, these are also issues that are rarely addressed in studies of popular music simply because most academics who study it do not use ethnography. But I believe that—beyond self-critique—such questions have much to contribute to our understanding of the social world from which popular music emerges. The recent ethnographic work of scholars such as Harris Berger (1999), Kai Fikentscher (2000), Dawn Norfleet (1997), Norman Stolzoff (2000), and especially Ingrid Monson (1996) have been particularly influential on me in this regard.

In preparing this study, I have spent time with a variety of producers (as well as MCs, deejays, businesspeople, and hip-hop fans). Although I have tried to collect a wide range of opinions on the issues I address, most of the producers I interviewed tend to hold certain qualities in common. Though some of the artists I spoke with are well known to hip-hop fans, most are what could be called “journeymen”: professionals of long standing who are able to support themselves through their efforts, who have the respect of their peers but have not achieved great wealth or fame. Virtually all are male, a fact which exerts a huge, if underarticulated, influence on the musical form as a whole. Although my consultants include a relatively small number of women, I believe that their representation in these pages is actually disproportionately large when compared to their actual representation in hip-hop (at least in the capacities with which I’m concerned).

Another significant demographic aspect of my sample is its ethnic diversity, which I feel accurately reflects the diversity of the community itself. That said, however, one of the foundational assumptions of this study is that to the extent that one wishes to think in such terms, hip-hop is African American music. Hip-hop developed in New York City in neighborhoods that were dominated by people of African descent from the continental United States, Puerto Rico, and the West Indies. As a result, African-derived aesthetics, social norms, standards, and sensibilities are deeply embedded in the form, even when it is being performed by individuals who are not themselves of African descent.

Scholars such as Robert Farris Thompson (1996), Kyra Gaunt (1997), and Cheryl Keyes (1996) have demonstrated this in very specific terms on both abstract and practical levels. Thompson (1996: 216–218), for example, traces the intervening steps between traditional dance forms in the Congo and b-boying or b-girling (also known as breakdancing), and Gaunt (1997: 100–112) connects rap’s rhythms to those of “pattin’ juba,” a tradition that goes back centuries. As I will demonstrate, traditional African American aesthetic preferences, social assumptions, and cultural norms inform producers’ activities on many levels.

Geographic diversity is another significant factor affecting the producers’ sense of community. I interviewed individuals from Atlanta, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Oakland, Philadelphia, and Seattle for this study. Virtually all of them knew each other, either directly or indirectly. This is a small community held together by phone, the Internet, and regular travel. Although such abstract communities have always existed to some degree, the increasingly global nature of communication and the international flow of labor and capital has made the nonlocal community an increasingly common affair (see Clifford 1992, Appadurai 1990, Slobin 1992). Benedict Anderson (1983), in fact, convincingly argues that even such an accepted political formation as the nation-state constitutes an “imagined” community. While this may have its practical difficulties for the ethnographer, it means that relationships are driven by the needs and sensibilities of the individuals in question more than by their proximity to centers of traditional power.

The ease with which such relationships can be maintained still surprises me. When I travel, I am regularly asked by hip-hop artists to deliver records and gossip to individuals in other cities. And as I write this, the Rock Steady Crew, a legendary b-boy/b-girl collective, is preparing to mark its twenty-fifth anniversary with a weekend of parties and performances here in New York City; two of my Seattle-based consultants will be deejaying there. And, of course, the Internet is probably the most powerful tool for communication between individuals and dissemination of general information; new Web sites appear every day.

In order to reflect this state of affairs, my research took a path that was unusual but entirely organic to the processes that I was studying. I began by interviewing hip-hop artists in Seattle, Washington, because I had preexisting ties to that community and because I believe that Seattle is exemplary as a node of the national network I am trying to portray. It is both large enough to support a substantial community of musicians and small enough to be constantly aware of its place within the greater social context. My consultants in Seattle introduced me to producers in other cities, allowing me to explore the network in a fashion similar to that of any other community participant, moving from the local to the universal. This is a practical example of the way the process of performing fieldwork can have a very abstract influence on the way a study is structured.2

In other words, my fieldwork was very similar to the educational process that a hip-hop producer would undergo, the primary difference being that I was producing a book rather than music. But the experience of meeting producers, convincing them of my sincerity, going digging and trading records with them, communally criticizing other producers’ beats, learning about production techniques and ethical violations through discussion and experimentation, and eventually being introduced to nationally known artists parallels the common pedagogical experience of hip-hop producers themselves in many important ways. I would argue that the shape of the knowledge expressed in this book—what I know and don’t know—is largely the result of this approach, and thus reflects the epistemological orientation of hip-hop production—or at least my own experience of it. A researcher setting out to interview the “great producers of hip-hop” or to produce a formal history of hip-hop production may well produce a different picture.

Finally, most of my consultants share a somewhat purist attitude toward the use of digital sampling for hip-hop production. While digital sampling has historically been the primary technology used for making beats, it is not the only one; some forms of hip-hop use synthesizers or live instrumentation as their foundations. One of the major premises of this project is that the distinction between sample-based and non-sample-based hip-hop is a distinction of genre, more than of individual technique.3 Hip-hop producers who use sampling place great importance on that fact, and—as I will show—find it difficult to countenance other approaches without compromising many of their foundational assumptions about the musical form.4

In fact, as I complete this book, sample-based production—once the central approach used in hip-hop—is becoming increasingly marginalized. This, in turn, has led some producers to become more open to other approaches, while others, in response, have become even more purist than they were when I began my research. There are two major reasons for these intertwined developments. First, due to the growing expense of sample clearance (i.e., securing permission from the owner of a copyrighted recording) as well as a general aesthetic sea change, many major-label hip-hop artists are increasingly rejecting the use of samples in favor of other sound sources. While many producers have embraced this change, it is seen by others as a threat to their aesthetic ideals and has caused them to redouble their efforts to emphasize sampling in their work. Second, the increased availability of PC- and Macintosh-based sampling programs has allowed large numbers of individuals who have not been socialized into hip-hop’s community or aesthetic to become involved in its production. This, too, has led those who already used sampling to articulate the previously unstated social values of the community, a trend which can be seen, for example, in the founding of Wax Poetics, a journal devoted entirely to various aspects of the search for rare records to sample (a pursuit known as “digging in the crates”—see chapter 4). Ultimately, then, this work—like all ethnographies—reflects the way a particular community defined itself and its art at a particular time.

Ethnography is well suited to address these and many other issues in popular music. It can ground general theoretical claims in the specific experience of individuals, lead the scholar to interesting questions that may not have arisen through observation alone, and call attention to aspects of the researcher’s relationship to the phenomenon being studied that may not be immediately apparent. This can deeply affect the work that is produced. And, perhaps most importantly, it can help the researcher to develop analyses that are relevant to the community being studied. This is especially valuable in the case of hip-hop, as the culture’s participants have invested a great deal of intellectual energy in the development of elaborate theoretical frameworks to guide its interpretation. This is a tremendous—and, in my opinion, grievously underutilized—resource for scholars. Engaging with the conceptual world of hip-hop via participant observation has been one of the most rewarding aspects of this project, and I have tried to reflect that in the pages that follow.

Another benefit of using participant observation to study popular music is that it allows the researcher to exploit the huge body of critical work on scholarly subjectivity that has emerged from the discipline of anthropology over the last thirty years. Critiques of reflexivity, the abstraction of human activity, and the idea of a discrete and bounded “field” are largely absent from writings on popular music because they are simply not relevant to the theoretical approach of most popular music scholars. Ethnography can bring these issues into the discourse.

I am particularly indebted to a recent piece entitled “You Can’t Take the Subway to the Field” (Passaro 1997), which discusses the definitional problems that arose when a researcher chose to do fieldwork among New York City’s homeless population. As Passaro suggests, the primary difficulty in this endeavor was maintaining a distinction between the subject of one’s study and the other aspects of one’s life, including the analysis of one’s data. The origins of this distinction, its nature, and its use as an instrument of postcolonial power have been discussed at length in the anthropological literature (most notably Said 1978, Fabian 1983, Marcus and Fischer 1986, Gupta and Ferguson 1997) As Johannes Fabian (1983) in particular has convincingly argued, the idea of an objective and distinct “field” removes the culture of the researcher from the study’s purview, despite the fact that it is often a deep and abiding influence on the processes being studied.5 One of the aims of this work is to use the particular nature of my own experience, particularly moments of social discomfort or awkwardness, to implicitly question the value of the distinction between “home/academia” and “the field.” In short, I feel that a researcher’s self-conscious confusion over the nature of social boundaries can help to highlight the extent to which the researcher imposed those boundaries in the first place. With that in mind, I would like to address briefly some of the factors that came into play in this study.

Perhaps the most obvious feature working against the researcher who wishes to maintain the separation between these two worlds is that they often occupy the same physical space. This alone cannot help but illuminate the extent to which the separation is an ideological one. Another reason for disorienting overlap is that the scholar is often not the only individual who moves back and forth, and the resulting malleability of social barriers tends to blur any strict distinctions. A number of individuals who had a professional interest in the hip-hop world (including S. K. Honda, DJ Topspin, DJ E-Rok, Jake One, and MC H-Bomb) attended the University of Washington while I was studying hip-hop as a graduate student there. Seven of the people I interviewed for this project (Wordsayer, Kylea, Strath Shepard, Mr. Supreme, DJ B-Mello, Harry Allen, and Steinski) have lectured to classes I taught.

Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon in action was a festival of African American music that I attended in Seattle in the spring of 1999. The chair of my doctoral committee, a visiting artist, and several graduate students from my department performed Trinidadian pan music; they were immediately followed on the same stage by a hip-hop show that featured a number of my consultants from an earlier investigation of this subject. In between sets, I found myself in a conversation with two members of my committee and two of the people I was “studying,” all of whom saw themselves simply as fellow participants in a musical event.

The inherently problematic nature of my relationship to the field served as an organic critique of the study itself at every stage of the process. Many of my consultants have approached me with new information or critiques that they wanted to share, sometimes years after I had initially interviewed them. At least one of the formal interviews as well as many informal discussions for this project were conducted in my home, a setting that in many ways reverses the power dynamic between interviewer and interviewee. Finally, I often unwound from a long day of writing by discussing my ideas with consultants in the backs of loud, smoky night-clubs in between their deejay sets. In other words, my fieldwork was itself a social process that interacted in manifold ways with the social processes that were the intended focus of this study. While this is of course true for anyone performing fieldwork, the difference in the case of Americans who study American popular music is that there is no formal beginning or end to our research; our participant observation (i.e., experiencing popular music within the context of American society) covers roughly our entire lives, as do the relationships that we rely on to situate ourselves socially.

I began to listen avidly to hip-hop in the mid-1980s and became actively involved in the Seattle hip-hop scene when I moved there to begin graduate school in 1992. Since then I have attended over five hundred hip-hop performances, club nights, or other events (an average of one per week for ten years). I began writing for Seattle’s now-defunct hip-hop magazine The Flavor in 1995, and I have subsequently written about hip-hop for the Seattle Weekly and the magazines Resonance, URB, and Vibe. After I began this book, I bought a sampler of my own and began to make rudimentary beats, sometimes playing them for my consultants. It is perhaps more significant at my beginner’s level of development that I have also found myself with an increasingly obsessive devotion to digging in the crates for rare records. In fact, when I attend academic conferences in different cities, my fellow hip-hop researchers (particularly Oliver Wang) and I often schedule an extra day to go record shopping. So when I’m digging through rare funk 45s on the floor of a tiny, dusty baseball-card store in Detroit with two people who were on my panel earlier in the day and a local hip-hop deejay, am I in the academic world or the field? I hope never to be able to answer that question. The use of participant observation and ethnography also means that the text that one produces is itself part of the social world one is studying. Its literary conceits often embody the relationship between the author and the context. I would therefore like to briefly discuss some of the choices I have made in transforming my research into a written text.

One decision that I have struggled with has been to refer to producers with masculine pronouns in most cases. This is not intended to be in any way prescriptive. I do not believe that producers “should” be male. But I do believe that most producers are male. Furthermore, it is clear (as I will discuss in chapter 2) that the abstract ideal of a producer is conceived in masculine terms and that this has a substantial effect on how individuals strive to live up to that ideal. I believe that the use of gender-neutral language would create a distorted picture of this process.

Similarly, I believe that specifying the ethnicity of particular producers who I quote in the following pages would also add distortions because the producers themselves did not make any such distinctions to me.6 I am not suggesting that ethnicity is never a concern for these individuals or that history and culture do not affect the musical choices that artists make. But I am saying that the producers themselves tend to de-emphasize its significance to their conduct as producers. As I argue throughout this study, there are no consistent stylistic differences between the practices of producers from different ethnic backgrounds. If there were a white or Latino style of hip-hop production, I think distinctions would be more justifiable. But, as I argue throughout this book, all producers—regardless of race—make African American hip-hop. And those who do it well are respected, largely without regard to their ethnicity. Given the charged nature of most multicultural interactions in American society, this facet of hip-hop culture is particularly remarkable. That fact became clear in my conversation with Steinski, a producer who is universally respected despite falling well outside of hip-hop’s presumed “black youth” demographic; he is white and, at the time of our interview, fifty-one years old.

Joe: Maybe I’m just being idealistic, but that’s something that I really like about … hip-hop. Which is like, “People liked it because it was good. End of story.”

Steinski: Totally. I mean, that’s been one of the best things about hip-hop. You know, that there’s a lot of room in it for new shit, for anomalous shit, for all kinds of stuff. You know, like, “Here we have some of the best deejays on Earth, and they are all Filipino American!” Well, you don’t see GrandWizzard Theodore sitting around going, “Those cats aren’t authentic—they’re not black!” It’s like, they’re hip-hop—that’s the only thing that matters, man….

Yeah, I think that part of it’s wonderful. That it’s kind of like, “OK, anyone who can drag themselves in over the windowsill—they’re in.” I mean, that’s really great—it was great then [in the 1980s], and it’s great now. That part’s really great. ’Cause otherwise, I’d be some asshole with a sampler, fifty-one years old, and who listens to me?7 (Steinski 2002)

Questions of what it means to “be hip-hop” and the relationship of that state of existence to African American culture in general are at the heart of this study and at the heart of hip-hop production itself. But it is clear that this is a deep connection that hinges on the aesthetic assumptions and implications of the work that any given artist produces, rather than, for example, on the espousal of Afrocentric beliefs. Cultural background, while influential, is not determinative. Stated in the most simplistic terms, the rules of hip-hop are African American, but one need not be African American to understand or follow them.

This openness is not simply a matter of largesse on the part of hip-hop arbiters. Rather, it is a result of social processes that are intrinsic to the act of making beats, particularly the complex set of ethical and aesthetic expectations that producers must follow in order to be taken seriously by others. To follow the rules, one must first learn them from people who already know. In order to learn them from people who already know, one must convince them that one is a worthy student.8 Thus the mere ability to follow the rules in the first place demonstrates that the individual in question has already undergone a complex vetting process, and the willingness to undergo that process demonstrates a commitment to the community and its ideals. This is presumably what Steinski is referring to when he mentions producers “drag[ging] themselves in over the windowsill”—there are dues to be paid, but once one is in, one is considered a full member of the community.

It is certainly possible that the apparent color-blindness of the producers’ community is an artifact of my own racial point of view (as a Jew, I would be considered white by most Americans). But given the nature of my personality and those of my consultants, it is difficult for me to imagine that they would downplay racial issues simply to avoid making me uncomfortable.9 In fact, I have discussed various racial questions with almost all of them in other contexts. Ultimately, though, this issue—whether I am underrepresenting the influence of race on individuals’ approach to hip-hop production—can only be answered satisfactorily by a nonwhite researcher. From a purely logical standpoint, I cannot assess my own blind spots—if I could, they wouldn’t be blind spots.

Another factor that particularly stands out in interview-based research is the disjuncture between the oral language of those who were interviewed and the written language of the author and secondary sources. In other words, my consultants’ comments were initially presented orally, improvisationally, and in response to questions that they had not seen beforehand, while scholars’ comments (both my own and quotations from other writers) were presented in written form, with (presumably) much forethought and revision. Moreover, many of my consultants speak African American English, even if they write Standard (i.e., European) American English. If one is not familiar with it, a written approximation of African American English—nonstandard by definition—may make the speaker appear to lack full linguistic competence. While such judgments are entirely the result of social prejudice, they may be reinforced by the textual juxtaposition of a quotation from a speaker of African American English and the broader text written in Standard American English. Generally speaking, I have followed Monson (1996) with regard to transcribing the speech of my consultants:

I have chosen to use nonstandard spellings very sparingly…. I include such spellings when they seem to be used purposefully to signal ethnicity and when failure to include them would detract from intelligibility. Since African Americans frequently switch from African American idioms to standard English and back in the same conversation … orthographic changes can represent linguistic changes that carry much cultural nuance. For the most part I have preserved lexicon, grammar, and emphasis in the transcription of aural speech.10 (Monson 1996: 23)

Beyond transcriptional choices, I have used three strategies to try to account for the occasionally jarring nature of these oppositions (oral versus written, African American English versus Standard English, improvised versus prepared), the first of which is simply to call attention to them. A second strategy has been, as often as possible, to include my own side of the conversation when I quote from interviews. In this way, I am able to present a record of my own oral expressions as an implicit point of comparison to those of my consultants.

Finally, I have shown drafts of this work to all of my consultants, in order to see that they are comfortable with the way their words are being presented as well as to make sure that my interpretations of their statements are consistent with what they actually meant. I believe that this is important, not only for ethical reasons, but also for simple accuracy. It is precisely the things researchers take for granted—our own assumptions about the way the world works—where we are most vulnerable and where our consultants can exert a decisively positive role.

The reader will also note that—unlike previous academics who have discussed hip-hop production—I tend to shy away from transcribing musical examples. Transcriptions (that is, descriptive graphic representations of sound) objectify the results of musical processes in order to illuminate significant aspects of their nature that could not be presented as clearly through other means. The core of this book is concerned with the aesthetic, moral, and social standards that sample-based hip-hop producers have articulated with regard to the music that they produce. I believe that transcription—or any other close reading of a single completed work of sample-based hip-hop—is more problematic than valuable for my purposes. There are four general areas of difficulty that bear on this question: the necessary level of specificity of a transcription, the ethical implications within the hip-hop community of transcribing a beat, the general values implicit in a close reading of a beat, and the specific deficiencies of transcription as a mode of representation with regard to hip-hop.

With regard to the level of specificity, most of the significant aesthetic elements I discuss are too general, too specific, or too subjective to be usefully analyzed through the close reading of any one beat. An example of an element that is too general is the myriad conceptual changes that a linear melody undergoes when it is “looped” or repeated indefinitely. An example of an element that is too specific is the microrhythmic distinctions that result in a beat either sounding mechanical or having what producers often refer to as “bounce.” Finally, there are a number of psychoacoustic criteria that must be fulfilled for a sample to have “the right sound.” All of these issues, I believe, are more usefully addressed through the producers’ own discourse than through the objective analysis of a given musical example.

Transcribing a beat also has ethical implications. In the community of sample-based hip-hop producers, the discourse of aesthetic quality is primarily based on the relationship between the original context of a given sample and its use in a hip-hop song; that discourse consists of assessments of how creatively a producer has altered the original sample. For various reasons that I will discuss, however, the community’s ethics forbid publicly revealing the sources of particular samples. Thus, while various techniques may be discussed, it is ethically problematic to discuss their realization in any specific case. This also means that when any two people present a producer’s analysis to each other they are each implicitly confirming their insider status. This valence is one of the most significant aspects of the analysis (it is manifested in record knowledge and technical knowledge as well as aesthetic knowledge). In other words, the prohibition and what it represents are as significant as the information being protected.

Finally, previous transcribers of hip-hop music, who were acting (implicitly or explicitly) as defenders of hip-hop’s musical value, have naturally tended to foreground the concerns of the audiences before whom they were arguing, which consisted primarily of academics trained in western musicology (see Walser 1995, Gaunt 1995, Keyes 1996, Krims 2000). This approach requires that one operate, to some degree, within the conceptual framework of European art music: pitches and rhythms should be transcribed, individual instruments are to be separated in score form, and linear development is implicit, even when explicitly rejected. While Adam Krims (2000) has moved the analysis away from specific notes and toward larger gestures, he has retained the rest of these conventions. I am not saying that these transcriptions are inaccurate, or even that the elements that they foreground are insignificant, only that they represent a particular perspective, which is, as I said, that of their intended audience: musicologists. My work, by contrast, is more ethnographic than musicological. As a result, I wish to convey the analytical perspective of those who create sample-based hip-hop music as well as those who make up its primary intended audience: hip-hop producers. Their analysis, I would argue, is not best served through transcription.

Most significantly, to distinguish between individual instruments, as in a musical score, obscures the fact that the sounds one hears have usually been sampled from different recordings together. Take, for example, a hip-hop recording that features trap drums, congas, upright bass, electric bass, piano, electric piano, trumpet, and saxophone. These instruments, in all likelihood, were not sampled individually. The overwhelmingly more plausible scenario is that the piece was created from a number of samples, one of which may feature upright bass and piano; another of which might feature drums, electric bass, electric piano, and trumpet; another of which may use only the saxophone; and another of which may feature only congas and trap drums. To present each instrument as playing an individual “part” is to misrepresent the conceptual moves that were made by the song’s composer. But it is not possible to understand these conceptual moves through listening alone, even if one is trained in the musical form. One can only know which instruments were sampled together by knowing the original recording they were sampled from, which brings us back to the ethical and social issues raised by revealing sample sources.

Similarly, pitches, as elements at play within a framework of tonal harmony, are rarely conceived of as such and even then are rarely worked with individually; rather, entire phrases are sampled and arranged. Choosing a melody to sample (after considering its rhythm, pitch, timbre, contour, and potential relationship to other samples) is very different from composing a melody to be performed later.

The use of ethnography also raises questions about the subjectivity of the researcher. For white people writing about African American music, of course, this is an age-old question. Unfortunately it is often answered with guilty soul-searching, a confident recitation of one’s credentials, or somewhat perfunctory admissions of outsiderness, all of which tend to be so particular to the individual in question as to be of little value to readers. One begins to move beyond the constraints of these strategies when one senses the underlying issues implicit in William “Upski” Wimsatt’s rhetorical question (which arose when he reflected on his own experiences in hip-hop culture), “Hadn’t I just been a special white boy?” (Wimsatt 1994: 30). In other words, when a white person does manage to forge a relationship with African American culture, there is a temptation to attribute this to some exemplary aspect of our own personality. While there may be some truth to this, it would be foolhardy—as Wimsatt convincingly argues—to ignore the larger forces at play. The difficulty lies in the fact that these forces manifest themselves primarily through our daily activities and interactions; it is often quite difficult to distinguish between one’s own impulses and the imperatives of the larger society.

I believe that the most productive approach to this issue is for scholars to create a framework in which their particular paths may be interpreted as case studies of individuals from similar backgrounds pursuing similar goals. In other words, reflexivity is not enough: one must generalize from one’s own experience, a pursuit which requires researchers not only to examine their relationships to the phenomena being studied, but also to speculate on the larger social forces to which they themselves are subject, a process that I would term “self-ethnography.” I have found the work of Charles Keil (particularly his new afterword to Urban Blues [1991]) and William Upski Wimsatt (1994) to be particularly valuable as models for such endeavors.11 To that end, I wish to discuss several aspects of my own life that may contribute to a broader understanding not only of my own project, but also of other such works created by researchers from similar backgrounds. In making this choice, I am intentionally avoiding the impulse to give a comprehensive explanation of my approach in favor of focusing of a few specific factors that I believe have been less exhaustively discussed elsewhere. These aspects include my ethnic and cultural background, social approach to scholarship, and age.

I was born in 1968 and raised in a predominantly white, Christian suburb of Hartford, Connecticut. I was introduced to participant observation at the age of five, when, according to my parents, I browbeat them into taking me to see Santa Claus at a large downtown department store. After a long wait, I made it to Santa’s lap and was asked what I wanted for Christmas. “Oh, nothing,” I replied, “We’re Jewish.”

This anecdote suggests to me that the experience of fieldwork was known to me at an early age and that it was used to define my own identity as a Jew in America. In other words, I was trying to understand what I was by engaging with what I was not. I knew Santa Claus wasn’t for me, yet I wanted to experience and understand him anyway. And I would suggest that for American Jews in general, day-to-day living in an ideologically Christian society (not to mention conscious self-definition) is always, to some degree, a process of participant observation. I believe that this social impulse combined with a general Jewish predisposition toward scholarship as a mode of social interaction (see Boyarin 1997) may help to account for the disproportionate Jewish representation in fields that make use of ethnography, such as anthropology and ethnomusicology.

A more specific social aspect of this particular project and its value to me personally is the scholarly approach that hip-hop producers themselves take toward collecting old records for sampling purposes. This dovetails nicely with my own tendencies as an ethnomusicologist, insofar as I enjoy collecting records, talking about the minutiae of popular music, and making distinctions between things that are so fine as to be meaningless to the vast majority of people who encounter them. To put it another way, I am a nerd. In a surprising number of cases, this was common ground upon which my consultants and I could stand.

Another useful approach may be to see my attraction to hip-hop production as a delayed effect of the cultural environment in which I was raised—particularly that of 1970s television. As David Serlin (1998) has pointed out, children’s shows of that era (especially Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and Schoolhouse Rock), presented multicultural utopias held together by what was, in retrospect, extraordinarily funky music.12 While hip-hop samples from a variety of sources, there is a particular focus on music that was originally recorded in the early 1970s, an era that corresponds to early childhood both for me and for many of the most influential hip-hop producers. I imagine that at least some of the pleasure we derive from hearing a vibrato-laden electric piano or a tight snare drum comes from the (often subconscious) visions they conjure up of childhood and the mass-mediated friendships of Maria, Gordon, Rudy, and Mushmouth, who smiled at us through our TV screens.

In addition to its sociohistorical context, this book also exists with the academic tradition of scholarship on hip-hop. The development of a cohesive body of literature on hip-hop music, though still in its early stages, has already been characterized by a number of discernable trends. These trends have been extensively documented by Murray Forman (2002b). I would like to focus on a specific aspect of the academic literature that has influenced this study: the dispersal of the literature on hip-hop’s precursors among a variety of academic disciplines, a situation that has unintentionally created an inappropriately fragmented portrait of hip-hop’s origins.

Hip-hop’s ancestors, when they have been studied at all, have been studied in ways that are not particularly related to music or to each other. I would distinguish five primary factors that contributed to the birth of hip-hop music: the African-American tradition of oral poetry; various kinesthetic rhythm activities, such as step shows, children’s clapping games, hambone, and double Dutch; developments in technology for the recording and reproduction of music, culminating in the use of digital sampling; attitudes in African American cultures regarding the value and use of recorded music; and general societal (i.e., social, political, and economic) conditions that made hip-hop an attractive proposition for inner-city youth. Any useful scholarship on hip-hop that wishes to be grounded in the literature is therefore necessarily interdisciplinary because it must begin by integrating the literature on these diverse subjects. Of the five areas I have delineated, only one—societal conditions—had been extensively investigated prior to the birth of hip-hop. This, I believe, is one of the reasons that its significance relative to the other four factors is frequently overstated in many discussions of hip-hop culture.

Scholarship that ties the remaining four areas to the birth of hip-hop is sparse, a state of affairs I would attribute to two factors: first, for various social reasons (particularly race, class, and gender), precursors to hip-hop, such as toasts, double Dutch rhymes, and so on, have not until recently been seen as warranting academic attention, and second, because this material was inconsistent in many ways with academic ideas of “music,” the literature that does exist is scattered among a variety of other disciplines, such as folklore and sociology. The literary tradition relating to hip-hop’s precursors, then, seems to encompass the literature of every discipline but music, from African American oral poetry (folklore) to the rhythms of double Dutch (developmental psychology and sociology) to the technological developments of South Bronx deejays (history, sociology, and postmodern literary theory). Hip-hop—as music—becomes literally unprecedented. This may create an unbalanced environment for hip-hop scholarship because the scholar must explain how a musical form such as hip-hop could appear instantly from nowhere.

While few address this question directly, it does emerge in the literature in the form of a striking ahistoricality. As Keyes has noted, “Postmodern criticism tends to define rap music in modernity, thereby distancing it as both as a verbal and musical form anchored in a cultural history, detaching it as a cultural process over time, and lessening the importance of rap music and its culture as a dynamic tradition” (1996: 224). When I refer to the ahistoricality of much of the contemporary literature on hip-hop, I am referring to the difficulties of putting hip-hop music into the context of a larger musical history and the resulting implication that hip-hop as a musical form is sui generis. There have been several excellent works that strictly concern the development of the broader culture (see Castleman 1982, George 1998, Hager 1984, Toop 1991). Craig Castleman’s work—essentially an ethnography of the graffiti-writing community in New York City (including police officers who try to stop graffiti writing)—has been a particular influence on this study. But most works on the musical facets of hip-hop present it as a discrete moment in time, and the few that do take a larger historical view almost universally follow the development of rapping, to the exclusion of other hip-hop arts. This has its benefits as well as its liabilities.

The primary benefit of such ahistoricality is that it implicitly presents history (i.e., a developmental paradigm based in linear time) as only one of a variety of possible settings for analytical work on hip-hop. Many of the works cited above primarily emphasize economic, social, and cultural contexts, all of which are valuable approaches. The liabilities emerge, however, when history is summarily excluded as a paradigm due to the paucity of source material or the requirements of a theory. While some scholars find that historical context is not relevant to their particular arguments, many imply that historical context cannot be relevant because hip-hop’s use of previous recordings from different eras automatically voids the paradigm of historical development. This, I believe, is a mistake. As Keyes notes above, hip-hop’s aesthetic is deeply beholden to the music of other eras, and an understanding of these sensibilities can only enrich our understanding of contemporary practice.

Furthermore, the boundary between hip-hop insiders and outsiders can be rather porous, a state of affairs that may be obscured when hip-hop is removed from its larger context. As I will show, the nature of the producers’ art requires them more than other hip-hop artists to explore beyond the genre boundaries of hip-hop. The producer Mr. Supreme, for instance, rejects the notion that a “true hip-hopper” should listen only to hip-hop music: “If you’re a real true hip-hopper—and I think a lot of hip-hoppers aren’t—like I always say, ‘It’s all music.’ So if you really are truly into hip-hop, how can you not listen to anything else? Because it comes from everything else. So you are listening to everything else. So how can you say ‘I only listen to hip-hop, and I don’t listen to this.’ It doesn’t make sense to me” (Mr. Supreme 1998a).

In fact, every producer I interviewed cited older musical forms as direct influences. An extreme example of this phenomenon arose in an interview with Steinski, who was a heavily influential figure in the development of sampling, particularly with regard to the use of dialogue from movies, commercials, and spoken-word records:

Joe: If you weren’t the first, you were one of the people that really popularized that idea of taking stuff….

Steinski: Oh, cut-and-paste shit? Yeah.

Joe: Were you the first person to really do that?

Steinski: I don’t think so.

Joe: OK, I guess “Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel”—

Steinski: Buchanan and Goodman. 1956. Did you ever hear the “Flying Saucer” records?

Joe: Oh, where they cut in—they ask the questions and they kinda … So you see that as an influence?

Steinski: Totally. More than an influence, it’s a direct line. Yeah. Absolutely, man. Those guys had pop hits with taking popular music, cutting it up, and putting it in this context. Totally. Yeah. Absolutely.13 (Steinski 2002)

If such influences are rarely seen in scholarly writing about hip-hop, it is largely because they do not answer the questions that scholars are interested in: What does hip-hop’s popularity say about American culture in the early twenty-first century? How does African American culture engage with the mass media? How does global capitalism affect artistic expression?

Although there have been several short works on the role of deejaying in live performance (White 1996, Allen 1997), there has been very little substantial work on sampling within a hip-hop context. In fact, to the best of my knowledge, there have been only three widely published academic works that focus specifically on sample-based musical gestures (Krims 2000, Walser 1995, Gaunt 1995). All three of these works emerge from a similar disciplinary perspective: musicology informed by personal experience with hip-hop music. All three authors provide insightful, provocative, and—particularly in Walser’s case—politically engaged analysis. But because they are musicologists, they focus on the results of sampling rather than the process; they are, essentially, analyzing a text.14 Again, each of these works stands on its own, but there is a resounding silence when it comes to other perspectives on hip-hop sampling—particularly when one considers that hip-hop has been a major form of American popular music for almost thirty years.

There are two primary reasons for the lack of attention that the non-vocal aspects of recorded hip-hop have received from academia. First, the aesthetics of composition are determined by a complex set of ethical concerns and practical choices that can only be studied from within the community of hip-hop producers. Most researchers who have written about hip-hop have not sought or have not gained access to that community. Second, most of the scholars who have studied hip-hop have emerged from disciplines that are oriented toward the study of texts or social processes, rather than musical structures. Simply put, it is not the music that interests them in hip-hop. But such an approach—legitimate on its own terms—does reinforce the notion that the nonverbal aspects of hip-hop are not worthy of attention. For example, Potter, in an otherwise excellent book, dismisses the instrumental foundation of hip-hop almost out of hand, beginning a chapter with the pronouncement that “[w]hatever the role played by samples and breakbeats, for much of hip-hop’s core audience, it is without question the rhymes that come first” (Potter 1995: 81; emphasis in original). In some sense, this entire study is devoted precisely to questioning this conclusion.15

The study begins with a brief history of sampling, questioning some of the assumptions that scholars have made about this history, which have subsequently influenced the general tenor of the scholarship on sampling. Specifically, I have tried to problematize the relationship between general societal factors—culture, politics, and especially economics—and hip-hop music, arguing that individual artists often have more control over the way these issues affect their work than they are given credit for. In other words, I am not so much interested in the conditions themselves as I am interested in the way hip-hoppers, given those conditions, were able to create an activity that was socially, economically, and artistically rewarding. In most cases, my approach can be expressed in three related questions: What are the preexisting social, economic, and cultural conditions? Given those conditions, what did the individual choose to do? Why was the individual’s choice accepted by the larger community?

The practice of creating hip-hop music by using digital sampling to create sonic collages evolved from the practice of hip-hop deejaying. The nature and implications of these developments are discussed in chapter 2. Also discussed in that chapter is the way that this progression is largely recapitulated in the lives of individual producers as part of an educational process that intends to inculcate young producers in the hip-hop aesthetic. This process is ongoing throughout a producer’s career and may affect many facets of hip-hop expression. In chapter 3, I address hip-hop producers’ embrace of sampling by examining their rejection of the use of live instrumentation. I argue that sampling, rather than being the result of musical deprivation, is an aesthetic choice consistent with the history and values of the hip-hop community. Chapter 4 addresses the social and technical benefits of digging in the crates for samples. In addition to providing useful musical material, the practice also functions as a way of manifesting ties to hip-hop deejaying tradition, “paying dues,” and educating producers about various forms of music, as well as a form of socialization between producers. Chapter 5 describes the so-called producers’ ethics, a set of professional rules that guides the work of hip-hop beatmakers. These rules reinforce a sense of community by providing the parameters within which art can be judged, as well as by preempting disputes between producers. Chapter 6 looks at the aesthetic expectations that guide producers’ activities. By critically assessing the producers’ own discourse of artistic quality, I attempt to derive the underlying principles that they have created. In doing so I argue that to a great degree these principles reflect a traditional desire among people of African descent to assimilate and deploy cultural material from outside the community while demonstrating a subtle mastery of the context in which it operates. The hip-hop aesthetic is, in a sense, an African-derived managerial philosophy. Chapter 7 discusses the influences that come from outside the producers’ community that may affect producers’ conduct. Using the sociologist Howard Becker’s (1982) notion of an “art world,” I look at the immediate material and social forces that help to define the hip-hop world as a collective enterprise.

A significant portion of my discussion concerns the ways in which social, artistic, and ethical concerns work together to construct a sense of relative artistic quality and how this sense of quality circles back to affect individuals’ social and artistic praxis.

It is useful to visualize these various levels of subjective quality (as judged by the producers themselves) as concentric circles with the center being the core of, the theoretically “best” approach to, hip-hop sampling. The outermost circle—the decision to use digital sampling rather than live instruments in the first place—reflects the purism of hip-hop producers in defining their genre (chapter 3). Once that decision has been made, the next circle consists of following producers’ ethics, which define what may be sampled and how this sampling is to be done (chapter 5). Finally, the most valued status to be claimed by producers—the core—is that of one who, having done these things, is able to produce a creative work (chapter 6). Each circle represents both a level of artistic quality and the group of people who have attained that level. The smaller circles are seen as existing within the larger ones, so, for example, all people who adhere to producers’ ethics use digital sampling, but not all people who use digital sampling adhere to producers’ ethics.16

This entire configuration is itself contained within a larger social world, whose concerns deeply and necessarily affect a producer’s output, another series of concentric circles.17 Once again, while it is assumed that members of the inner circles abide by the outer, the reverse is not true. These outer circles include other members of the hip-hop industry, such as MCs, record company representatives, and radio and nightclub deejays, as well as fans. In chapter 8, I argue that this entire structure constitutes what Becker (1982) has called an “art world”—the total social network required to produce and interpret a work of art.

In the epigraph that opens this book, Mr. Supreme relates the common experience of hip-hop producers being questioned about whether or not hip-hop is “really” music. Whenever I speak about hip-hop production, this is almost always the second question I’m asked.18 As I take pains to point out, it is actually a question about what the word “music” means, and it contains the hidden predicate that music is more valuable than forms of sonic expression that are not music. If one believes that only live instruments can create music and that music is good, then sample-based hip-hop is not good, by definition. The real question, in other words, is, “Can you prove to me that hip-hop is good?” And the appropriate answer, in my opinion, is “No, because it depends on what you personally consider to be valuable; hip-hop is what it is.” This is essentially what Mr. Supreme is doing by creating an analogous argument about painting: if you believe that musicians should make their own sounds, then hip-hop is not music, but, by the same token, if you believe that artists should make their own paint, then painting is not art. The conclusion, in both cases, is based on a preexisting and arbitrary assumption.

In fact, the question itself is a trick: it loudly directs one’s attention towards hip-hop’s formal characteristics, while quietly installing its own prejudices about what music is supposed to be. The process is similar in both form and intent to the concept of the “noble savage” as explicated by Ter Ellingson (2001). By focusing on the question of whether or not savages were noble, the term’s inventors were able to reinforce the ideas of “nobility” and “savagery”—both of which were deeply flawed—while simultaneously drawing attention away from them. Similarly, to be drawn into an argument about whether hip-hop lives up to the standards of other cultural forms can only weaken hip-hop’s own internal values, and hip-hop producers clearly understand this. For thirty years, in fact, the hip-hop community has steadfastly refused to compromise its aesthetic principles in deference to the majority society.

If hip-hop is revolutionary, then this—even more than its lyrical message—may be where its power truly lies: in the fierce continuity of its artistic vision. And that, ultimately, is what this book is about. Which is why I consider it a statement of both intellectual honesty and political commitment to say that I love hip-hop. I love the crack of a tight snare drum sample, the feel of bass in my chest, and the intensity of a crowded dance floor. “They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)” by Pete Rock and C. L. Smooth (1992) is not only a fine example of the sample-based hip-hop aesthetic. It is also one of the most beautifully poignant songs I have ever heard, and it never fails to send chills down my spine. It is these chills that are often lost in academic discussion. It is these chills that motivate hip-hop producers to devote their time and money to sample-based hip-hop. And it is these chills that have drawn me to produce the following study.