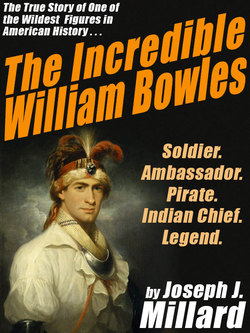

Читать книгу The Incredible William Bowles - Joseph J. Millard - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

As long as he lived Will Bowles would remember that Friday, the first day of October, 1776, with deep bitterness and an anger that never cooled. It was the day he was first swept into the maelstrom of blind hatred and savagery men called the American Revolution. It marked the end of the pleasant life he had known and the beginning of a chain of fantastic adventures that would rock the three greatest nations on earth to their very foundations.

This one began much like any other weekday with the four mile walk to the school in Frederick Town and the perpetual struggle to spur the lagging steps of his younger brothers. The responsibility fell upon Will, since he was the eldest and practically a grown man now, with his thirteenth birthday only a month away.

The ten-year-old Thomas was becoming a little more manageable, but seven-year-old John could find mischief enough for two. Next year, Will reflected moodily, little Catharine would be starting school and then he’d really have his hands full. One good thing, by the time the baby, Mary Neil, was ready to start, he’d be graduated and gone and the burden would be on Thomas’s shoulders.

A heavy rain in the night had left great mud puddles and Will was driven to distraction keeping the younger boys out of them. The rolling Maryland countryside had a bright, fresh-washed look. The air had a wet, leafy smell, with just a tang of approaching winter in it. Beyond Frederick Town the wooded slopes of the Catoctin Mountains flamed with autumn colors.

Will was some yards ahead of his dawdling brothers when he reached the school yard. He started to turn in and stiffened with a sharp premonition of trouble.

Just inside the yard the rain had left a large puddle. The older boys were all gathered beside this in a huddle, whispering and snickering. At Will’s approach they all fell suddenly silent, watching him with curiously intent expressions.

In the center of the group Will saw the bristling red thatch and hulking figure of Garfield Roebaum, the biggest and oldest boy in school and a notorious bully. Beside Garf was his admiring shadow and imitator, Alvin Tomes. The presence of the two was proof enough of some unpleasant mischief brewing, and it was obvious Will was the intended victim.

There had never been any love lost between him and the pair, but they had never come to blows. Will was tall for his age and, although slim of build, he was wiry, hard-muscled, and fast. Garf and his crony had prudently confined themselves to sly tricks and verbal abuse. Because of Will’s dark eyes, black hair, and olive complexion they had lately taken to taunting him with being half-Indian. Will had tried to ignore them, not from fear but because the penalty for fighting in the school yard was a severe caning at the hands of schoolmaster Moab Hudkins.

That thought, and a glimpse of the schoolmaster’s long, horsey face peering from a window, decided Will. Instead of following the direct path that would take him past the boys, he swung left to skirt wide around the other side of the puddle.

He was directly opposite when the group suddenly parted. Will had a glimpse of Garf s big hands flying up and out to release a rock bigger than a man’s head. There was no time to jump back. The rock struck the puddle with a mighty splash and a sheet of muddy water flew up to engulf him from head to foot.

Choking and half-blinded, Will pawed at his face, hearing hoots of raucous laughter. He spat out a mouthful of gritty mud and cried furiously, “What’d you do that for?”

“Why, Big Chief Runny Nose,” Garf said loudly, with mock astonishment, “I thought you’d like it. You’re a king-loving Tory, ain’t you? All Tories are pigs and all pigs like mud.”

The crude sally brought another chorus of laughter. At the sound his rage exploded into white-hot fury. Dropping his sodden books in the mud, he doubled his fists and charged across the puddle at his tormentor.

“William Augustus Bowles!”

The roaring voice of schoolmaster Hudkins burst through Will’s blind rage and stopped him dead, just short of his target. The teacher charged up, gripping his oak cane, his long face dark with anger. He glared at Will.

“We’ll have no more of that.” He shook the cane in the air. “Get along to your classes. It’s time and past for school to start.” As Will took a step, he barked, “Not you, William Augustus. You’ll not track that mud and filth into my clean schoolroom. Go home—and while you’re about it, take your brothers with you.”

For the first time, Will became aware of the two younger boys, standing back with their mouths agape. He turned to the teacher. “But they weren’t near enough to be splashed, sir. Why can’t they go along to their classes with the others?”

“Because they’re not wanted here any more,” Hudkins thundered. “None of you is wanted, so don’t try to come back. The school is crowded enough with the sons and daughters of patriotic Americans. We have no room for Tory traitors who would sell out their own country for allegiance to a tyrant king.”

For a moment, Will was too stunned to think or speak. Then a wave of hot anger washed over him.

“My father is no traitor but a loyal Englishman and a man of importance in Frederick County. He has been on the board of trustees for this school since it was formed in 1768. He was chosen to select the land and build this school. He raised the money to pay for it and he hired you as schoolmaster. He’ll have something to say about whether or not we go to school.”

“Your father,” Hudkins said through his teeth, “has already had far too much to say to suit decent citizens. You can tell him that while his beloved king wears royal robes, Mr. Thomas Bowles may find himself wearing a coat of tar and feathers if he doesn’t curb his tongue.”

He spun around, took a step, then whirled back to roar, “As for the board of trustees, they met last night and voted unanimously to replace him with a good American patriot. So begone, the lot of you, and don’t ever come back.”

Will could only stand in stunned silence, his clenched fists tight to his sides, his cheeks dark with the hot blood of anger. Young John was the first to break the silence.

“Whee!” he shouted joyfully. “We don’t have to go to school.”

* * * *

Thomas Bowles was at the tobacco barns, directing the colored field hands as they strung the bundled leaves on poles to be hung for curing. He was a big man with a grave, pleasant face and an air of quiet dignity that befitted the position he had so long held in the community. Ever since his arrival from England in 1758 he had been active in civic affairs.

He had indeed been responsible for building and financing the school. When the money pledged fell nine hundred dollars short of needs, he had personally organized a lottery that raised the balance. He had even taught for a time until a suitable schoolmaster could be hired. In addition, he had long served as clerk of Frederick County and for the past twelve years had been deputy county commissioner. Meanwhile he had built up a prosperous tobacco plantation that enabled his growing family to enjoy modest luxury.

When he spied the three boys trudging up the road, he let go of the curing pole he was holding and hurried to meet them. Will’s mother saw them at the same time and burst from the house, her face anxious.

“William Augustus,” she cried in horror, “whatever on earth happened to your clothes? And what are you three doing home at this time of a school day?”

“We don’t have to go to school any more ’cause we’re Tories,” John shrilled happily. “What’s a Tory, Pa?”

“You’re too young to understand. Run along and play with your sisters.” He turned to Will, his face suddenly grim. “I think I can guess what happened, William, but tell me all the details.”

When Will had finished his story, his mother clasped her hands and cried, “Thomas, it can’t be true. They wouldn’t dare turn you off like that after all you’ve done for the school.”

“I’m afraid they would, Eleanor,” the elder Bowles said. “I’ve been expecting it. I hadn’t wanted to tell you, but on Monday last I was notified that my services to the county were no longer welcome and my positions had been filled by patriotic Americans. They passed a resolution that no English loyalist be allowed to hold a public post.” His mouth set in a harsh, bitter line. “They have turned ‘loyalty’ into a dirty word.”

“But Thomas, to think they could stoop so low as to vent their hates on children.”

“The way Samuel Adams and John Hancock have inflamed the mindless rabble with their rantings about liberty and independence, no one—man, woman, or child—who remains faithful to his king and country will be spared.”

Young Tom had already lost interest and wandered off but Will stood rooted, his mind in a turmoil. He had been hearing such talk between his parents for many months without giving it his close attention or really understanding what it meant. Now suddenly, with his own personal involvement, this growing bitterness between loyal Englishmen and rebel “patriots” took on a new and deeper meaning.

“What can we do, Pa?”

“The first thing,” his father said soberly, “is to see that you and your brothers continue your education. Judge Kennerly is a man of superior education and refinement who has unfortunately fallen upon hard times. I am quite sure he would welcome a few extra shillings for giving you boys private tutoring. I’ll ride in now and make the arrangements.”

“Oh, Thomas,” his mother cried. “Do be careful.”

“Don’t worry, Eleanor. I have learned something these past days. That pack of unwashed patriots has gone too far in their madness to listen to reason, so I’ll not waste any reason on them. Hereafter, no matter how they rave and prattle, I shall keep a tight rein on my tongue and avoid stirring further trouble. This will all be over in a matter of weeks, anyhow. We can expect any day to hear that General Howe’s forces have captured New York and wiped out the ragged rabble George Washington calls his Continental Army. Once that is accomplished, this insane fever to separate from the mother country will be stamped out quickly.”

He went to the door, then stopped with his hand on the latch and looked sharply back at Will. “You take that advice to heart, too, young man. You’ve a tendency to be altogether too free with your opinions and quick with your tongue at times. Getting yourself beaten up, or worse, will benefit neither you nor England. I want your promise to remain quiet at all costs.”

“All right, Pa,” Will said reluctantly. When the door had closed, he whispered fiercely under his breath, “I’m glad Pa didn’t think to ask a promise about my fists.”