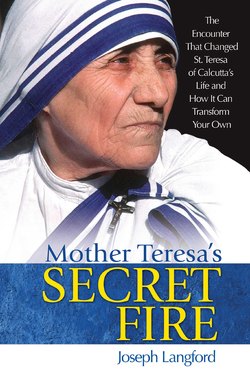

Читать книгу Mother Teresa's Secret Fire - Joseph Langford - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree

Calcutta: Backdrop to an Epiphany

Calcutta sunrise. Even at this early hour, noisy, bustling, hot.

Humidity rides the air; from the shops of Chowringee to the hovels of Moti Jhil, it clings to the waking city like second skin. This is the hot breath of Kali — evil goddess who devours her husbands — for whom legend suggests the city was named.

Calcutta’s sixteen million inhabitants begin to stir. Many wake to another day on the sidewalks, huddled under cardboard and tattered cloth. Out in the streets, Calcutta’s traffic begins to move and swell, like a great sea overflowing its borders. Along the lanes and side streets, diesel fumes mix with sandalwood and the sweet smell of cooking fires, far away.

Crows caw noisily overhead, perched in trees and on housetops, arrogant and oblivious. Down on the sidewalk, men squat on the cracked cement smoking bidis and shooing flies, as they pore over the morning paper. Further up the road near Sealdah station, vendors display their wares piled high and spilling onto the footpath, circled by a moving sea of sandals and bare feet.

Along the sides of the road, rickshaw pullers run, swallowed up in smoke and traffic. Sun-bronzed and wizened they go, carrying the uniform-clad children of wealthy families to their private schools, while dodging walkers and hawkers and trams. Huge steel-sided buses ply the main roads, coughing and straining. They hurtle down the streets swollen to overflowing, with riders perched on the sides and hanging out windows and open doors. At each stop, they slow to a crawl, disgorge their passengers, and take off again spewing billows of smoke. Auto-rickshaws weave in and out of traffic, dodging and darting like insects, avoiding oncoming cars by inches and seconds.

Further out on the periphery, barefoot men push their handcarts, piled high and bound for market. They trudge on, amid clouds of mosquitoes, incessant horns, and the non-stop buffeting of passing trucks and speeding buses.

There, on the outskirts of the city, begin the slums that are Mother Teresa’s Calcutta, notorious for their pavement dwellers, street children, scavengers, and disease. Though greatly improved in recent years, in Mother Teresa’s time this area had become a cliché for the worst of human poverty. This would be Mother Teresa’s domain for the rest of her days — her meeting place with God in the poor, and our meeting place with God in her.

To gain a better idea of what Mother Teresa faced when she stepped out of the convent with five rupees in her pocket, let us take a closer look at one of the more famous of Calcutta’s slums, the ironically named “City of Joy,” which once claimed one of the densest concentrations of humanity on the planet: two hundred thousand people per square mile:

It was a place where there was not even one tree for three thousand inhabitants, without a single flower, a butterfly, a bird, apart from vultures and crows — it was a place where children did not even know what a bush, a forest, or a pond was, where the air was so laden with carbon dioxide and sulfur that pollution killed at least one member in every family; a place where men and beasts baked in a furnace for the eight months of summer until the monsoon transformed their alleyways and shacks into lakes of mud and excrement; a place where leprosy, tuberculosis, dysentery and all the malnutrition diseases, until recently, reduced the average life expectancy to one of the lowest in the world; a place where eighty-five hundred cows and buffalo tied up to dung heaps provided milk infected with germs. Above all, however, [it] was a place where the most extreme economic poverty ran rife. Nine out of ten of its inhabitants did not have a single rupee per day with which to buy half a pound of rice…. Considered a dangerous neighborhood with a terrible reputation, the haunt of Untouchables, pariahs, social rejects, it was a world apart, living apart from the world.7

Even amid such extreme poverty, Mother Teresa discovered in the poor of Calcutta a nobility of character, a vitality of family ties and cultural wealth, and an inventiveness and ingenuity that made her genuinely proud. “The poor are great people,” she vigorously insisted. These were people she deeply admired, and of whom she was undyingly fond. She insisted that the two-way exchange that passed between her and the poor of Calcutta was forever tipped in her favor; that she received much more than she gave, and was ever more blessed than she was blessing.

Children sleeping under a portrait of Mother Teresa (Raghu Rai/Magnum Photos)

Volunteers

After their day’s work in the slums, Mother Teresa and her Sisters would return to north-central Calcutta. Here was Mother House, her headquarters, from which hundreds of Sisters would go forth each day to give comfort and care.

Once her mission began to be known outside of India, young people from far and near began offering to help with her work in Calcutta. From all over the world they came, young volunteers in Mother Teresa’s army of love, giving a week or a month or more to help her Sisters serve the poorest of the poor.

Every morning the faces of these young foreigners could be seen moving along the swarming sidewalks, walking up Lower Circular Road on their way to morning Mass with Mother Teresa and her Missionaries of Charity. Later, after a breakfast of chapattis (Bengali flatbread) and home-brewed chai, they would set out for the Kalighat, with its narrow lanes and shop fronts festooned with flower garlands for the gods, on their way to the Home for the Dying. Here they would spend their days changing bandages, comforting the sick, and tending to the dying, alongside Mother Teresa’s Sisters and Brothers.

After their initial struggles with the heat and the food and the difference of culture, these mostly First World youth would often find a new joy and sense of purpose stirring within — an experience often denied them by their affluent life abroad. As the days melted into weeks under Calcutta’s merciless sun, they would slowly discover that while they were touching the poor of Calcutta, God himself was touching the less-accessible, less easily admitted poverty of their own souls. Changed from within, they would return home with new answers and a new peace. But they arrived with new questions as well; questions about the life-changing closeness to God they had experienced amid the squalor and hardships of Calcutta. Questions, too, about the smiling, sari-clad woman who had gently opened their hearts to God. Who was this Mother Teresa, and what made her special? What inner flame did she carry that had kindled their hearts, and brought light into their darkness?

In the Darkness, Light

But before investigating her light, some may ask: How could there be such luminosity in someone whose interior was buffeted by darkness?

Looking back over her life and the documents that have emerged since her death, it is clear that Mother Teresa’s inner (and outer) world was a place in which the brilliance of God’s light and the bleakness of man’s darkness met and mingled — from which her victorious light only shone the brighter. What emerged from that inner struggle was a light in no way lessened by her bearing the cloak of humanity’s pain, but a light all the more resplendent, and all the more approachable. The kind of divine light we saw in her was no more the restricted domain of mystics and sages, but a light entirely accessible to the poorest, beckoning to God’s brightness all who share in the common human struggle.

In the wisdom of the divine plan, God sent Mother Teresa into the Calcuttas of this world — large and small, visible and hidden — so that precisely there, where our world (our inner world as well) appeared its darkest, the light he gave her might shine most brightly. Even more than to bring his comfort to the poor, God sent Mother Teresa to be his light. He invited her to pitch her tent in the blackest of places, not to build hospitals or high-rises, but that she might shine with his radiance.

Mother Teresa’s darkness was neither deviation nor mistake. Rather than being a divine miscue, her journey through the night had a definite and deeper purpose in God’s plan. Besides bringing her to share the dark struggle of Jesus on the cross, and the struggle of the poorest of the poor around the world, her darkness was intended as a light for the rest of us. Her night was a metaphor for the blackness of our “vale of tears,” a cartographer’s map etched on her soul to lead us through our own spiritual darkness into divine light. Paradoxically, her darkness became the vehicle for a much greater light, a light it could neither conquer nor contain, but only amplify, as it passed through her soul as through a prism.

A Message Meant for All

The energy and impetus for her new life came not only from her encounter on the train to Darjeeling, but from the message God had communicated to her there — a message revealing the immensity of his love for us, especially in our weakness and struggles. Throughout her life, Mother Teresa would cherish this message in her heart, and model it in all she did.

Mother Teresa shared her message with all who would hear — from Haiti’s President Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who had forgotten his own people starving outside his palace, to the rumpled man on L.A.’s skid row who had forgotten his own name. She knew that the greater our need, the greater our inner or outer poverty, the greater even our sin and moral failings, all the greater was God’s yearning for us. For Mother Teresa, the impulse that led the Good Shepherd to leave the ninety-nine and go in search of a single lost sheep was no longer a mystery, for she had experienced it herself; the same divine impetus had taken possession of her life.

In the months following Mother Teresa’s Nobel Prize, I offered to show the film portraying her work, Something Beautiful for God (later a book by the same name), to any group that was interested. I was invited to churches, civic organizations, schools, and gatherings of every sort — only to find the audience in tears by the end, so moved that they would queue up to offer me donations to send to Calcutta. I was witnessing not just the attraction of Mother Teresa, but the perplexity she caused, as people struggled with the newfound surge of generosity welling up inside them. Curiously, most of the audience seemed unable to find any deeper, more enduring response beyond tears and a hurried check.

Once I understood that people had difficulty extracting Mother Teresa’s message simply from what they saw on screen, I began giving a talk after the film — trying to help them make sense of what they had seen, and deal with the intense feelings the film had stirred up in them. I told them what Mother Teresa herself would have said — that there was no need to go abroad, nor even across town, to imitate her or to do something significant with their lives. She would have pointed to the suffering in the hidden Calcuttas all around them — in their own homes and families and neighborhoods, in the blind man down the street or in the unforgiven relative, forgotten behind the walls of a nursing home. These were all Calcuttas-in-miniature, where Christ, hidden under his “distressing disguise,” awaits our “hands to serve and hearts to love.” As Mother Teresa reminded every audience she addressed, whatever we do to the least of our brothers and sisters, we do it to him (cf. Mt 25:31-46).

Calcutta’s extremes of physical poverty, and the inner pain it brought to the hearts of the poor, were largely foreign to Western audiences. It took a new level of understanding for people to transpose Mother Teresa’s heroic charity in far-off Calcutta into small, seemingly un-heroic gestures of goodness and compassion in their own lives and limited surroundings. They were being challenged to alleviate the same pain of spirit they had seen on the screen, but hidden this time behind the manicured lawns and peaceable facade of their own neighborhood.

Only by explaining the applications of Mother Teresa’s message to every life did my audiences begin to bridge the gap between Calcutta and home, between the material poverty of the third world and the spiritual poverty that was theirs. In the end, God was asking of them, and of us, the same kind of generosity lived by Mother Teresa — only lived in a different setting, and practiced in a different way.

Mother Teresa never asked or expected her hearers to contribute to her work by sending a check — instead, she would suggest that they “Come and see” the work of her Sisters, and learn to spend time with the poor and needy, to give of their heart and not just their pocketbook. Writing a check was easily done, and easily done with. It allows us to do “charity,” while keeping at bay the inner tug that urges us to give more of ourselves and our time, rather than our possessions. This was the challenge people faced, as they discovered that the tug of conscience and heart Mother Teresa awakened both frightened and fascinated them at once.

Mother Teresa would point out that no matter how noble our intentions in giving monetarily, both God and neighbor needed more and better. God had not sent us a check in our need, but his Son. He gave of himself, without measure — as any of us can, anywhere we are, and whenever we choose. We are the ones called to help those around us, not Mother Teresa, not her Sisters in the far corners of the Third World, who have already done their part and more. We are the ones already there, living on the same street, in the same neighborhood, where so much hidden suffering and need go unheeded. We are the ones sent by God, anointed and equipped to give of ourselves to those he has placed around us. We need no special abilities or resources to do the work of love; we need “only begin,” even in the smallest ways. Mother Teresa knew that even the smallest seeds of charity could yield a rich and lasting harvest, had we but the courage to roll up our sleeves and begin. She would invite her audience to take some concrete step, no matter how small, to serve those around them, to put God’s love and theirs into “living action.”

In deference to the invitation of her friend, Pope John Paul II, Mother Teresa spent the greater part of her later years sharing this message with audiences worldwide, from kindergartens to the plenum of the United Nations. John Paul had asked her to proclaim God’s love especially in those places where he could not go — places ravaged by war and hardship, and wherever political realities prevented him from visiting, such as the then Soviet bloc, and the vast expanse of the Muslim world.

If Mother Teresa’s encounter and message were of such importance, why haven’t we heard of them — or why have we heard so little? The main reason is that she chose to live out the grace of her encounter in her own life first, in silent service to the neediest, before sharing it with her Sisters or the world. Because of her long silence, not only the importance of her message but its very existence may come as a surprise, even to her admirers. This had been her great secret, from 1946 on. This was the inner flame that led her through her dark night of the soul, just as the column of fire that led Israel through the desert long ago.

Apart from the grace of Mother Teresa’s encounter on the train, nothing adequately explains her. Nothing else can fully account for the life she led, or the extraordinary things she accomplished. Mother Teresa was more than merely a female Albert Schweitzer. She was above all a mystic, although a mystic with sleeves rolled up, whose spirit scaled the heights even while her body bent lovingly over the downtrodden and the dying. By exploring the secrets of her deep mysticism in the chapters to come, those who already knew Mother Teresa will know her better, and those who knew her only via the media will come to know her soul.

Her encounter and its message were, in the divine plan, more for us than for her. While this book is about the transformation Mother Teresa’s encounter produced in her soul, more than anything else it is about God and about the reader — about what Mother Teresa learned about God and how he sees each one of us, how he longs for intimacy with us, and for the chance to remake our lives as he did hers. More than about God’s message to Mother Teresa, this book is about God’s message through her, to you who read these lines. It is surely her hope, from her place in the kingdom, that this message laid once gently on her soul, and retold in these pages, might touch and transform your life even as it did hers.

“The experience of 10th September is [something] so intimate….” 8

—St. Teresa of Calcutta