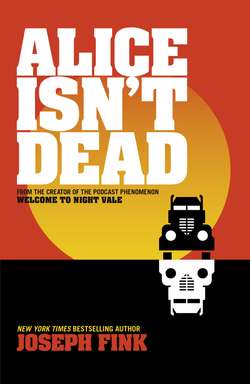

Читать книгу Alice Isn’t Dead - Joseph Fink, Joseph Fink - Страница 12

5

ОглавлениеIt’s a long and desolate way from Florida to Atlanta. The landscape is constructed of billboards. There are no natural features, only a constant chatter along the side of the road. A one-sided conversation. Lots of anti-evolution stuff. Advertisements for truck stops with names like the Jade Palace or the Chinese Fan, written in racist faux-Chinese fonts, and wink-wink language about the massages available. Keisha winced. Lord, get her to Atlanta. At least there was cruise control, and a road so straight all she had to do was make sure she didn’t go crashing off into a billboard telling her the Confederacy still could win, which was an actual billboard she had passed. The subtext of America wasn’t just text here, it was in letters five feet tall.

Business wasn’t booming. Many of the ads on the billboards were ancient. Announcements of local fairs from 2005. Fire sales for stores long since buried under pitch and concrete. A lot of vacancies, phone numbers to call for renting the space. She wondered how much an ad on a stretch like this would cost. Even on her wage she might be able to buy herself one, maybe this bare one between an ad for dog grooming whose tagline was DECADENT DOGS and yet another thinly veiled ad for sex work. She could reach out to Alice that way, even if Alice could never respond. Shout at the passing cars long enough and maybe someone somewhere would hear it. Or, hell, she could pick up her radio again and tell her entire story to every bored trucker in range. But instead she would keep driving, keep moving, and hope eventually she would arrive somewhere. A conclusion, a great transformation, or, failing that, Atlanta by the afternoon.

She was weighing the merits of stopping for a coffee when she spotted a billboard that didn’t fit. For one, it was spotless, installed maybe in the last week. It was a black billboard that said in tall white letters, HUNGRY? Was it advertising the concept of food? The idea of eating? If so, it wasn’t effective, because when she looked at it her gut twisted. The billboard pointed her somewhere bleak and horrible, even as her conscious mind hadn’t picked out why.

Another billboard, a few miles later. Same design; black background, white text, plain capitalized letters. BERNARD HAMILTON, it said. Then another that said SYLVIA PARKER. With each one she felt sicker and sicker. Someone was sending a message to someone, and the message felt to her monstrous and wild.

After Alice’s funeral, Keisha had mourned privately for weeks, refusing to see friends, missing work. She had sat at home and allowed the grief to weigh on her, a physical pressing on her chest that strained the muscles if she tried to get up or even turn her head. If she had had someone else to look after, a child, an elderly relative, even a pet, then maybe she would have forced herself into something resembling the person she had been before. But even then, inside she would be a vessel of fluids and mourning. She wasn’t the person she had been before and she never would be again. Sure, she had always been anxious and shy, but it had never been what defined her. She was able to relax when with friends and family. She had her hobbies and dreams. For some time she had been thinking about quitting her job to start a bakery, because the idea of arriving to work at four in the morning to make bread sounded like the best possible job in the world, but it had never been quite the right time for her to do that. All those parts of her were gone. It wasn’t only Alice who had died. Each death leads to smaller, invisible deaths inside the hearts of those left behind.

Alice never called Keisha by her name. This is true for many couples. Chipmunk, Alice would call Keisha. Chanterelle. Often Chanterelle. Walnut Jones. Alice found that last one especially funny. Now everyone called Keisha by her name. “Keisha,” they would say, in soft and worried voices, and Keisha just wanted someone with a laugh in her voice to call her Chanterelle, to call her Walnut Jones.

It wasn’t an intervention from her friends that broke her out of her stasis, although to their credit they tried. Showing up with food and with concerned frowns and busy hands tidying a house she couldn’t care less about. But none of them were able to reach her. Because they were trying to reach the Keisha they had known, and that Keisha was gone. No, it was not her friends who changed her, but that after two months she grew bored with her absolute grief, and so she pulled herself up against the weight of it and started going to grief counseling groups.

She sat in circles and described the shape of the monster that was devouring her. Because that’s what, as a civilization, we do. We try to talk our way through the ineffable in the hope that, like a talisman, our description will provide some shelter against it. But the monster continued to devour her, no matter how specific her description of it, no matter how honest the shell-shocked sympathy of her fellow mourners.

And when she wasn’t describing Alice, over and over talking about Alice, as though her wife could be resurrected with stories, Keisha watched the news. The news was good, full of tragedy and loss that had nothing to do with her. So many people in pain, she couldn’t possibly be alone, even though she felt as alone as could be. And then, six months after the funeral, somewhere in the third hour of Keisha’s daily news binge: a murder, brutal, somewhere in the Midwest. Bystanders gawking, standing in a circle and trying to describe with only their faces the shape of the monster they had seen. Behind the witnesses being interviewed, unmistakable, staring at the camera as person after person babbled their way through the horrible story—Alice. Keisha laughed, and then sobbed, and then threw up, and then looked again and there was Alice still, looking back at her, not dead at all.

The names on the billboards kept coming. One every three miles. TRACY DRUMMOND. LEO SULLIVAN. CYNTHIA O’BRIEN. They felt more like a memorial than an advertisement.

At the next stop she pulled off the road and searched the names, one after the other. It didn’t take long, because one name was connected to the next, and most of the articles were the same articles. Anxiety bubbled in her blood.

Found near major highways all over the country. Lives torn short under overpasses, on frontage roads, in broad wooded shoulders. Lost even in the age of GPS and Siri. Gashes on thetorsos. Defensive wounds on the hands. Victims of an unsolved serial killings from a murderer who reporters had nicknamed the Hungry Man. The nickname came from the single common thread between all the murders. A human bite on the neck or shoulder or armpit. Not elegant pinpricks, the romance of a vampire, but ragged and clumsy. Every name was a human being who had died alone on the sides of highways. Or, worse, not alone.