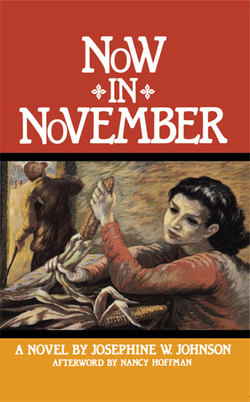

Читать книгу Now in November - Josephine W. Johnson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

THOSE years went slowly for us. Slow because heavy with the weight of things done, and the greater weight of things unfinished and still to be learned. The seasons washed one into another and were never still, but there was no swiftness nor anything but calm and gradual change. Sometimes not even that, but a shifting back and forth of seasons . . . long stretches of rain in the December mud, and a wind like April over winter snow . . . late pea-vines springing up at Thanksgiving, and marsh-violets in the sleet, and at times the orchards would be white in autumn, the trees wasting their strength before the spring. And there was the double life, the two parts not within each other nor even parallel. The one made up of things done day after day with comfort and soberness, hard sometimes but solid—things you could lay your hands on and feel that they were there: the saucepans and heavy dishes, the thick cups and the five beds to be made—things without any more mystery than the noon sun had. The open life and the one that was greater of the two, calm, prosaic . . . rational. And there was the inner walking on the edge of darkness, the peering into black doorways . . . the unrevealed answer which must be somewhere, and yet might not be even present or hidden in that darkness . . . this under-life which when traced or held to was not there, and yet kept coming back and thrust up like an iron dike through the solid layers of the sane and understood. The moment of self-searching, of standing under the oaks at night and asking—What? Who? What am I? . . . and the moment of feeling the self gone, lost or never existent. Where am I, God? . . . the terrible desire to understand . . . the moment of realization that there are some things that are neither bad nor good, nor ever to be classified . . . the strangeness that Kerrin had . . . things that like shards of a meteorite imply the presence of worlds beyond comprehension or understanding. And there was the desire for source—the desire to understand cause, which is the heart-root of religion, and led the mind through such devious and dark tunnels, and brought it out nowhere. These years marked by the dark torment of adolescence—that time when a fallen nail unlifted or a tuft of sheep’s wool is torture at night with fear and accusation. When dreams are portent or promise, and there is meaning and symbol in the crossing of two branches or a shadow’s length. . . . But all the time in the back of these things there was the hill-quiet and the stony pastures, and sometimes they made me ashamed of being what I was—human and full of a thousand wormy thoughts and selfishness, but more often they were like hands to heal.