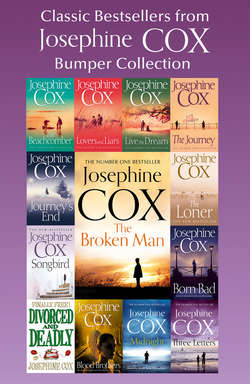

Читать книгу Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection - Josephine Cox - Страница 71

Chapter 6

Оглавление‘COME ON, YOU lazy pair!’ Dave’s voice sailed through the house. ‘Let’s be having you.’

‘What’s up?’ Sleepy-eyed, Amy leaned over the banister. ‘Is there a fire or what?’

‘There will be if you don’t get your backsides down here.’ Positioning himself on the second stair, Dave told her, ‘It’s ten past six. I’ve made the fire, boiled the kettle and now I’m ready for my breakfast.’

Amy glanced at her parents’ bedroom door. ‘Where’s Mam? Why didn’t she get up with you?’

‘Because she likes her bed too much, that’s why.’ Banging the banister again he pleaded, ‘Go and knock the door … tell her I’m ready for off.’

Amy groaned. ‘It’s surely not that time yet, is it?’ So far there had not been one day when the shop was late opening.

‘Happen not. But it soon will be if you don’t get a move on. So shift yourself, lass. And wake your mam up, will you?’

Grumbling and moaning, he lumbered into the kitchen where he checked the gas-ring. ‘Damn thing, it’s allus going out.’ Striking a match on the range, he lit it again. ‘One o’ these days I’ll chuck the bloody thing in the river and be rid of it once and for all!’

Glancing at the mantelpiece clock, he groaned. ‘Jesus! I’m getting nowhere at this rate.’

Making his way to the bottom of the stairs, he called up again, ‘MARIE … AMY! What the devil’s keeping you?’

Halfway to her parents’ room, Amy turned and came back. ‘What now?’

‘Did you wake your mam up?’

‘Not yet, but I will if you’ll give me a chance.’

‘Look, lass … get her out, will you? I can’t be going to work without summat inside me … I’d make my own breakfast, but you know what happened the last time I tried cooking on that blessed gas stove!’

‘And how could we ever forget?’ Having been woken by the yelling and shouting, Marie emerged fully dressed from her bedroom. ‘By! You should be ashamed … a grown man who can’t fry an egg without setting fire to the kitchen.’ Coming along the landing, she winked at Amy who by now was wide awake.

Relieved to see Marie already out and fighting fit, he called up, ‘Come on, lass. I don’t want to be late.’

‘Stop your moithering. I’m on my way.’ Starting down the stairs, Marie noticed how Amy was shivering. ‘Aw, lass, you’ll catch your death o’ cold. You go and get yerself dressed,’ she instructed in her best no-nonsense voice, ‘while I make a start on the breakfast.’ She feverishly rubbed her hands together. ‘By! It’s bitter cold! I hope your dad’s got a good fire going.’ Giving Amy a little push, she urged, ‘Go on, lass. Get dressed.’

‘Thanks, Mam.’ Drawing her robe tight about her, Amy felt the cold right through to her bones. ‘Don’t worry about my breakfast,’ she told Marie, ‘I’ll do myself a boiled egg and toast when I get down.’

Marie wagged a finger. ‘Your breakfast will be on the table soonever you’re ready,’ she promised. ‘Now go on. Be off with you.’

Amy didn’t argue. It would not have made any difference anyway. ‘All right, Mam, thanks. I’ll not be long.’

Hurrying back to her bedroom, Amy winced as the bare feet struck against the cold lino. It was November now, and the winter’s cold seeped into every corner, yet even in summer the warmth of the sunshine could not seem to find its way in, not even when every window in the house was open.

Grabbing her clothes, she went along to the bathroom, where she quickly cleaned her teeth and washed herself. A few minutes to brush her hair and she was ready for the day ahead.

Humming a tune to herself, she danced down the stairs and burst into the kitchen, where her parents were already seated at the table.

‘You look nice, love.’ Always ready with compliments for his two women, Dave looked up from his forkful of bacon. Taking note of Amy’s pretty blue jumper and the dark flared skirt that fell to just below the knees, he saw how her eyes sparkled and her brown hair shone, and he was curious. ‘Off somewhere special, are we?’

‘Only as far as the shop.’ She sat down, her egg and toast already on the table. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘No reason.’ He winked mischievously. ‘You wouldn’t be seeing a fella would you, lass? I mean, in my experience, when a young lady has that particular sparkle in her eye, it’s usually because she’s found herself a fella.’

‘Well, I’m sorry to disappoint you,’ Amy answered with a shy little smile, ‘but I haven’t “found a fella”, and nor am I likely to … unless he comes into the shop for a packet of drawing-pins or a pound of cheese.’ Strange she thought, how her father’s words made her think of the handsome man who visited the café on a Tuesday.

‘No fella, eh?’ Dave sighed. ‘Ah, well, it’s a terrible shame, that’s all I can say … especially when you look pretty as a picture this morning.’ Dave had never fooled himself about his darling daughter. Amy was a kind and wonderful young woman with a beautiful way about her that attracted all manner of compliments, but she was not what you might describe as pretty. She was more than that, he thought proudly, and he would not have her any other way. That rogue Don Carson had let her down badly, but she was probably well out of it. Don had been a bit too slick for Dave’s liking – he’d always suspected there was something not quite trustworthy about him. Shame he’d broken his little girl’s heart, though. Her confidence had been badly shaken. It’d take a special fella to make her trust again.

‘You may not know it, lass,’ he went on, ‘but you’re a real head-turner – bright and winsome, like a ray of sunshine, that’s what you are.’ He was inwardly pleased when she flushed with embarrassment.

Having heard and seen the exchange between husband and daughter, Marie chuckled through her toast. ‘Tek no notice, lass,’ she told Amy. ‘Your father’s allus had a silken tongue. He’s the world’s best flatterer … Matter of fact it wouldn’t surprise me if he doesn’t chat up the girls wherever he goes.’

‘Nonsense!’ Dave took umbrage at her remarks. ‘Why would I do a thing like that?’

She gave Amy a sly little wink. ‘One pretty smile from some wayward girl, and he’d be putty in her hands.’

Dave would have none of it. ‘There’s only two girls in my life,’ he declared sombrely, ‘and they’re right here at this table!’

It wasn’t long before the conversation turned to more serious matters. ‘Anyway, what are you doing up so early?’ Chopping off the top of her egg, Amy cut her toast into long thin soldiers. ‘You don’t have to be at work until eight.’

Taking a deep gulp of his tea, Dave pushed back his chair. ‘Mr Hammond is giving us a pep talk this morning and he wants us all in by half-past seven.’

Marie looked up. ‘What kind of pep talk?’

‘God only knows.’ He frowned. ‘We shall just have to wait and see.’

‘Are you worried about your job, Dad?’

Dave shrugged. ‘We’ve all been worried, Amy,’ he imparted quietly. ‘Work seems to be slowing down of late, and I’m told that two of the wagons were parked up for the best part of last week. On top of that, half the factory floor is completely empty.’ He looked from one to the other. ‘Some of the lads who’ve been there since Hammonds started up say they’ve never seen it like that before.’

‘Oh, Dave, I hope he’s not setting some of you off. I know how much you like your job.’ Marie knew that when work ran short, the rule was always last in first out.

‘I’m sure it won’t come to that, lass.’ Seeing their worried faces he assured them, ‘It’ll be summat and nowt, you’ll see. And besides, the brush production side of it has never been busier. While the two wagons have been parked up, the brush delivery vans have been on the go as usual. Look, don’t worry. I’m sure there’ll be an explanation for the slow-down on the other side.’

Marie nodded. ‘Happen you’re right, love.’

But she was uneasy all the same.

Dave left in plenty of time. ‘I’ll see you both later,’ he said and, with a twinkle in his eye, he told Amy, ‘This fella you’ve got in your sights, don’t keep him all to yourself, lass. Me and your mam would like a glimpse of him some time or another.’ And with that, he went away whistling.

However, when he got out of earshot, the whistling stopped. ‘I hope Hammond’s not about to finish some of the workforce,’ he muttered. ‘I don’t want to lose my job. I can’t go back working in the shop, not now our Amy’s given up her own job to help her mam. And, oh, I did hate being cooped up.’

Striding along in the cold morning air, he felt like a free man. There was something about being outside, even when he was driving along in his wagon – something so natural and satisfying, he would be greatly sad to lose it.

‘Morning, Dave.’ The big man was a loader at Hammonds. ‘I’m not looking forward to this ’ere meeting, I can tell you.’

‘Morning, Bert.’ Dave greeted him with a friendly nod, though his voice carried a worried tone. ‘Do you reckon we’re in for the chop then?’

‘Oh, aye.’ The big man’s expression said it all. ‘I reckon some of us are bound to be finished. What with the building half empty and two wagons stood off, we must be losing orders. I can’t see Hammond keeping a full workforce on, however good a man he is. Can you?’

As they turned the corner of Montague Street, they saw the tram about to pull out. Setting off at a run, they leaped onto the platform and hurried to sit down.

‘I think you might well be right,’ Dave said, squashing himself next to the big man who was taking up two-thirds of the slatted seat. ‘And if he is getting shut of some of us, I’ll surely be one of ’em,’ he contemplated. ‘Last in first out, isn’t that what they say?’

‘Mmm.’ Preoccupied with his own predicament and the missus with a new babby on the way, Bert didn’t answer straight off. Instead he stared absent-mindedly out the window, his mind turning over what Dave had said. ‘It doesn’t allus work out that way,’ he replied presently. ‘Sometimes they get rid of the older ones first. And that’ll be me included.’

They spent the rest of the journey in silence. There was much to think about, and the more they thought, the more anxious they became.

While Luke straightened his tie at the hall mirror, Sylvia looked on.

‘Why are you going so early this morning?’ Drawing near, she looked proudly at his reflection in the mirror. Immaculate in a dark blue suit, with white shirt and dark tie, he looked every inch the employer gentleman. ‘You look especially smart today.’

She reminded herself that he looked smart every day when he was going to his work. But on a Tuesday, he didn’t go to his work. She knew that because she had given Georgina the slip when they were out shopping and gone to his factory once, and he hadn’t been there. ‘He never comes in of a Tuesday, miss,’ some helpful, misguided lad had told her.

So, in spite of her enquiries and much to her consternation, she still did not know where he went on Tuesdays. She had asked him many times, but he always fobbed her off. ‘Work doesn’t present itself,’ he told her. ‘I need to put time aside to go looking for it.’ Which, even Sylvia knew, was no lie.

‘I have to be at work for seven fifteen,’ he answered her question.

‘Why?’ She hated it when he left in the mornings.

Used to her inquisitions, Luke answered her again. ‘Because I’ve called the men together for a special meeting.’ Leaning sideways he gave her a sound kiss. ‘It wouldn’t go down well if I was late, would it now?’

‘And what about me?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I don’t want you to leave me, that’s all.’

Concern showed on his face. ‘What’s wrong? Is there something you’re not telling me?’ He had tried hard to read the signs but her moods were so unpredictable, it was impossible to know.

‘No there isn’t!’ She began to grow agitated. ‘I know what you’re thinking, though,’ she snapped sulkily. ‘Go on then. Why don’t you ask me if I’m about to go crazy?’ She was painfully aware of the times when she lost control, and afterwards, filled with shame and fear, she knew little about what had taken place. During that dark period when her mind went into some kind of chaos, she was totally helpless.

Lately, because of something her sister said, she had convinced herself it was the price she had to pay for taking a lover outside her marriage. Sometimes Georgina said things like that – things that made Sylvia feel bad, and which she found hard to forget. Georgina had always had a spiteful streak. Sometimes they were such friends – like sisters ought to be – and then Georgina would be mean. When they were little, Mummy had said Georgina was just jealous, when Sylvia told tales of her, and to take no notice. But now Sylvia found it hard to cope with her sister’s unkindness, which, as ever, could strike out of the blue.

Now as she goaded him, the fear was etched in her face. ‘Go on, Luke! Ask me if I’m about to lose control!’

Turning, he took her gently by the shoulders, his voice soft with compassion. ‘And are you,’ he asked, ‘about to lose control?’ There were times when she took him by surprise. One minute she would be perfectly normal, and the next she would be like a raving lunatic, hitting out at anything and anybody; smashing whatever she could lay her hands on.

It was at times like that, when he feared she might harm herself.

‘Stop fussing.’ Pushing him away, she suddenly smiled. ‘I’m fine,’ she lied. ‘In fact, I’ve never felt better.’

‘So, what did you mean just now when you said, “What about me?”’

‘Like I said … I don’t want to be left alone, that’s all.’ A little flurry of fear turned her insides over.

Astonished, he asked, ‘Do you really think I would leave you alone?’

Just then the rear door opened and Edna popped her head round. ‘Seven o’clock, Mr Hammond,’ she said with a homely grin. ‘And here I am, as promised.’

Sylvia’s face lit up. ‘Edna, it’s you!’

‘Well, it isn’t anybody else, you can be sure o’ that,’ came the chirpy reply. ‘Now then, who wants a brew?’

‘Not for me, thanks.’ Concerned about the time, Luke told her, ‘I’d best be off or I’ll be late.’

‘Well, it won’t be because I let you down,’ she declared. ‘I were out of my bed a full hour afore time on account o’ you.’ She wagged a finger as she told him mischievously, ‘O’ course, I’ll be wanting overtime money, you understand?’

He tutted. ‘Oh, I’m not sure I can promise anything like that,’ he teased. He and Edna understood each other very well.

Having already removed her coat and slung it over her arm, she pretended to put it back on. ‘I’m sorry, sir.’ Her voice was firm but her smile was growing. ‘If you aren’t going to treat me right, I shall take leave of you.’

Sylvia chuckled. ‘Behave yourselves! Stop teasing her,’ she chided Luke. And turning to Edna, she told her firmly, ‘And you’re just as bad. “Overtime money”, indeed. We’ve always looked after you and always will.’

Looking mortified, Edna curtsied. ‘Sorry, ma’am,’ she stuttered contritely. ‘Please don’t sack me. I won’t do it again.’

With a little laugh, Sylvia asked, ‘Didn’t you say something about “making a brew”?’

Edna laughed out loud. ‘I’ll make it right away,’ and she departed the room in a burst of merry laughter.

‘Edna is pure gold,’ Luke said. ‘She’ll take good care of you, and before you know it I’ll be back home.’

Sylvia nodded. ‘I should have known you wouldn’t leave me on my own,’ she apologised. ‘I’m sorry I was surly before.’

He slid his arm round her waist. ‘It’s all right.’

‘You’re so patient with me,’ she answered softly. ‘Any other man would have left long since.’

‘No they wouldn’t,’ he assured her, ‘not if they loved you as much as I do.’ Yet though he loved her, he was not in love with her. Sadly, with her affair with Arnold Stratton, and its consequences, she had severed that very special bond that held them together as man and wife.

It had been of her choosing, when she’d taken another man in place of Luke. But she was still his wife and, as far as he was concerned, that gave him certain responsibilities.

‘Kiss me, Luke … please.’ Like a spoiled child, she gave up her face for a kiss and he obliged. ‘I’ll come to the door with you.’ Taking hold of his hand, Sylvia went with him to the front door. ‘What’s this meeting about?’

‘I’ll tell you when I come home,’ he promised.

‘Tell me now!’

‘There’s no time now.’

‘I won’t let you go until you tell me!’ The smile remained, but the voice began to quiver.

Edna appeared on cue. ‘Now, now, dear. Let your husband get off,’ she urged gently. ‘He has important things to see to. Let’s you and me go and sit down for a few minutes, eh? I’ll make you some toast and marmalade, what about that?’

For a long, worrying moment, the younger woman stared at Edna, then she smiled at Luke, a coy little smile. ‘I’ll let you go,’ she told him, ‘for another kiss.’

Bending to kiss her on the mouth, he assured her, ‘We’ll talk when I get home. All right?’

Her smile widened. ‘Yes … all right.’

‘That’s my girl!’

‘Come on then, my dear,’ Edna said. ‘I hope you haven’t forgotten, we’re going shopping today.’

Sylvia appeared not to be listening. Instead she was standing at the open door, her gaze following Luke as he went to the car. A moment later he was gone and she was still waving. ‘It’s all right, he’s gone now.’ Edna would have closed the door but Sylvia put her foot there.

‘Why did he have to go early?’

‘He’s promised to tell you all about it when he gets home, and you told me yourself, he’s never yet broken a promise. Come on now, let’s go and get that toast on, eh?’ Edna had learned to read the signs. ‘Close the door, then we’ll go into the kitchen you and me.’

Ignoring her, Sylvia waved after Luke until her arm ached and when she turned it was with an expression of disbelief. ‘He’s gone!’

Edna quietly smiled. ‘That’s right, my dear … he’s gone to his work. So don’t you think you should close the door now?’ When Sylvia made no move, she stepped forward to shut out the cold morning air.

‘NO!’ Catching her heavily across the shoulder with a fist, Sylvia hissed through clenched teeth, ‘You leave it!’

Clutching her shoulder, Edna gave her a hardened stare. ‘Keep hold of yourself, child,’ she chastised harshly. ‘I meant only to close the door.’

‘There’s no need. Look, I can do it myself.’

With a sly little grin, Sylvia took a step sideways, then, gripping the edge of the door, she slammed it shut with all her might. The shuddering impact rattled the nearby shelf, sending ornaments crashing to the floor.

For a long, nerve-racking moment both women stared at the broken china.

Suddenly, the silence was broken with what sounded like a child sobbing, ‘Don’t punish me … please. I didn’t mean it.’

Before Edna could stop her, Sylvia had picked up a long shard of broken glass, crying out in pain when the sharp edges cut into her flesh. ‘Oh, Edna, look what I’ve done.’ All sense of reason had gone and in its place was the innocent fear of a child hurt. Holding the offending arm up for Edna to see, she began wailing. ‘I’ve done something bad, haven’t I?’ She appealed to the older woman with sorry eyes, ‘What’s wrong with me, Edna?’

Her cries collapsed into sobs and Edna’s heart went out to her. ‘It’s all right, my dear,’ she murmured. ‘You’ll be all right.’ But she would never ‘be all right’. Both Luke and Edna knew that, and maybe, deep down in the darkest corner of her mind, Sylvia knew it too.

The tears of remorse were genuine, as Edna knew all too well. ‘I’ll take care of it, child,’ she soothed, leading her away. ‘Once it’s washed and cleaned, it’ll be good as new.’

A swift examination told her that this time the wound was only flesh deep, thank God.

It was Luke Hammond’s father who had started the brush-making factory. Twice it had almost gone under and twice he brought it back to profit.

Luke grew up with it. He learned the art of business at an early age and had been groomed to deal with men on all levels. Like his father he respected his workers and was well trusted. Also, like his father he had a tireless passion for the business.

After his father was gone, he had taken up the reins and developed the business further. Now it was two businesses rolled into one. On the one side was the production of brushes: scrubbing brushes; horse brushes; yard sweepers, and anything that cleaned as long as it had bristles. Brushes of any kind had been the original backbone of the Hammond business and they still were.

But now there was another business growing alongside; a business started by Luke and which served others. There were many other companies in industrial Lancashire – some small and just starting out, and which had neither the capital nor premises to store the goods they produced. This was where, only a few years back, Luke had seen an opportunity.

Thanks to his father, he was fortunate to own a warehouse and factory premises of sizeable proportions, with room to spare for the brush-making business. ‘I have ample space,’ he told the owners of the small businesses at various meetings he’d arranged. ‘And I intend purchasing a fleet of wagons, so if we can close a deal, I’ll not only take your goods for storage, but I’ll deliver them as well. We can agree a long-term contract, or a short one that will let you out should you decide to expand your own concern.’

His intention was to provide such a good service that they would have no reason to sever relations.

Just as he had hoped, the idea was well received. Terms were agreed, and deals made, and it had turned out to be the best thing Luke had ever done.

News of the success of the arrangement spread, and it wasn’t long before larger, more established company men were knocking on Luke’s door. ‘We need to diversify,’ they said. ‘Our factory space is desperately needed for production and right now we have no wish to purchase other premises, but if we could utilise our present storage area and sell off our wagon fleet, we could grow our businesses overnight.’

Deals were struck that allowed Luke to take over old wagons, which had since been exchanged for newer ones.

Luke’s distribution business prospered, though its downside was that whenever one of his customers took a wrong turn and went under, Luke lost a sizeable slice of his business’s turnover. This had happened a few times, and on each occasion it threatened a serious step back.

This was what his employees now feared: that there had been others who had taken that ‘wrong turn’ and now it was themselves who were about to lose their livelihoods.

And so this morning, when they would learn their fate, they gathered from all parts of the factory: from the brush-making side, where the machines clattered all day and both men and women worked them with expertise, some cutting out the wooden shapes that would make the brush-tops, some feeding the bristles into the holes that were ready drilled and cleaned, and others fashioning and painting the handles.

When the production line produced the finished articles, the packers would neatly set them into boxes and the boxes would be carted away for delivery.

By nature, this was a dusty, untidy area, with the smell of dry horsehair assailing the nostrils, and the fall of bristles mounting high round the workers’ feet. Yet they loved their work and many a time the sound of song would fill the air.

The other side of the premises was cleaner, with mountainous stacks of boxes and parcels from other factories as well as Hammonds, all labelled and ready for delivery, and the four wagons in a neat row outside waiting to be loaded.

For the past few days, however, there had been only two wagons waiting, with the other two stationary further up the yard. Rumours had circulated, unease had settled in, and now, the mood of worried workers was so palpable, it settled over the factory like a suffocating blanket.

From his office at the top of the factory, Luke watched the workforce gather in the front yard. ‘They’re in a sombre mood,’ he told the clerk.

‘Aye, they are that, Mr Hammond.’ A ruddy-faced Irishman with tiny spectacles and tufts of hair sprouting from his balding head, old Thomas kept his nose glued to his accounts book.

Luke had some fifty people in his employ, and seeing them gathering in one place like now, it made a daunting sight, which filled him with pride and a sense of achievement, and also with apprehension. ‘They’re a good lot,’ he told the clerk.

‘Aye, they are that, Mr Hammond.’ Licking his pencil Thomas made another entry in his ledger.

Luke turned from the window to address him. ‘I expect they’ll be wondering why I’ve called them together like this.’

This time, Thomas glanced up. ‘Aye, they will that, Mr Hammond.’ The old man had been with Luke’s father before him, and was a loyal, trustworthy man who knew everything there was to know about the Hammond business.

Looking away, Luke smiled. ‘You’re a man of few words, Thomas.’

Thomas gave a long-drawn-out sigh. ‘Aye, I am that, Mr Hammond.’ Now as he glanced up, he smiled a wrinkly smile. ‘A man o’ few words, that’s me, so it is.’

Realising all the workforce were now gathered and waiting, Luke straightened his tie and fastened the buttons on his jacket. ‘It’s time,’ he said, opening the door. ‘I’d best tell them why they’re here.’

Downstairs, the atmosphere was one of apprehension. There were those who expected to be finished on the day, and others who prayed they might be allowed another few years of work and pay before they were put out to pasture.

‘Ssh! Here he comes!’ The word went round, a hush came down, and, hearts in mouths, they watched Luke’s progress as he came down the staircase.

‘If I’m for the chop, I’ll sweep the streets rather than be cooped up in the shop, a grand little place though it is.’ Being a man with an appetite for fresh air, Dave Atkinson was adamant he would find outdoor work.

‘I’m sixty-two year old,’ said another man. ‘Who in their right mind will tek me on at my time o’ life?’

‘Ssh!’ The ruddy-faced man in front turned round. ‘He’s here now.’

When the muttering was ended and the workers’ attention was on him, Luke revealed the reason for their being there. ‘Firstly, I want to thank every one of you for your loyal service and dedication to this company …’

‘Bloody hell!’ Half-turning to Dave, the ruddy-faced driver whispered, ‘That sounds a bit final, if you ask me.’

‘Ssh.’ Dave gestured towards Luke. ‘We’d best listen to what he has to say.’

Luke went on: about how proud he was of them all, and how, ‘I would have told you before but I had to wait and be sure.’

Recalling the endless meetings and frustrations of the past weeks, he took a moment to formulate his words. ‘I’ve had to do some hard talking these past few weeks and I don’t mind admitting there were times when I despaired. But I got there in the end, and now I can tell you that the future looks good, and we’re about to expand. The premises will be doubled in size and the fleet increased to eight wagons – the old ones going two at a time, until we have all eight exchanged for brand-new ones.’

With the workforce’s full attention, he continued, ‘All this will take time but, as you can see, two of the wagons have already been set aside for a ready buyer. I’ve secured two long-term contracts with sizeable companies based in Birmingham, and the hope of another in the pipeline.’

For a long, breathless minute, the silence was deafening.

Clenching his fist, Luke punched the air. ‘That’s it, folks! GO TO IT!’

He may have said more, but his voice was suddenly deafened by the biggest cheer ever to have been heard in that yard.

‘GOD BLESS YER, SON!’ Like many others, delighted and relieved, the ruddy-faced driver was leaping in the air, fists clenched and tears swimming in his eyes. ‘We all thought we were for the bloody chop!’

Tears turned to laughter, and Luke went amongst them, with congratulations coming from all sides. He was deeply moved by the loyalty of these ordinary, wonderful people.

‘Back to work now,’ he told them, and with smiles and much chatter they ambled away and, well satisfied with his own considerable achievements, Luke returned to the office.

‘These good people have made this business what it is today,’ he told the old Irishman.

‘Aye, they have that, Mr Hammond.’ Thomas wondered what Luke’s father would have had to say about what had happened just now, because in all the years he’d sat at this desk, he had never witnessed such a great surge of devotion as he’d seen today.

‘If you don’t mind me saying, Mr Hammond, I think you’ve forgotten something, so yer have.’

‘Oh?’ Turning from the window where he was enjoying his employees’ good humour, he asked, ‘What’s that then, Thomas?’

Thomas took off his spectacles, as he habitually did when about to say something serious. ‘The men may well have “made” the business, as you so put it. But it’s you they look up to, and it’s you that inspires them, so it is.’

Having said his piece, he smiled to himself, discreetly blinked away a tear, and got on with his paperwork.

Later, Luke discreetly observed his employees, content at their work. He wondered what his father would think about this new turn of events. A twist of regret spiralled up in him as he reflected, and not for the first time, how he had no son to hand the business on to. Somehow, a child had not happened, and now it seemed all too late.

His thoughts turned to Sylvia.

Why had she given herself to a man like Arnold Stratton? Had he himself let her down as a husband? Had he worked too long and hard, sometimes building the business, sometimes trying to keep it afloat? Had she been lonely? Was it all his fault? Time and again, he had asked himself that.

And yet when he looked back, he had not seen any real signs that she was unhappy or lonely. At that time she had many friends; all of whom had since deserted her when she needed them most.

She had been a busy, fulfilled woman who lived life to the full. He made sure they spent a great deal of time together. Since the day he met her, he had loved her with all his heart and had believed she loved him the same.

And yet she had found the need to seek out a man like Arnold Stratton. It was a sobering thought. He could not understand. Had she never really loved him? Did she secretly yearn for the greater excitement he could not give her?

And now, with the lovemaking ended and her injuries taking their toll, there would never be a child and she was like a child herself: helpless; frightened. All she had in the world were the two people who really cared: himself, and the devoted Edna. But, though they would do anything for her, they could not perform the miracle she needed.

In his mind’s eye he could see his painting of Sylvia. In that painting he had captured her beauty and serenity. If he was to paint her now, the fear and madness, however slight, would show in her eyes and mar her beauty. Arnold Stratton had done that and now he was in prison for what had happened to Sylvia. And rightly so!

The feeling of sorrow turned to a cold and terrible rage. If only he could have stopped it happening. If he could get his hands on that bastard, he’d make him pay for every minute he and Sylvia had been together. He imagined them in bed, naked, and his mind was frantic.

Stratton was where he belonged. A long spell in prison was not punishment enough for what that monster had done.

His unsettled thoughts shifted to another painting, hidden away in his sanctuary. It was a painting of another young woman. A woman with mischief in her eyes and the brightest, most endearing smile. A woman not of the same kind of beauty as his wife, but with something he could not easily define, not even in the painting of her.

She was alive! He only had to glance at the painting and it would make him smile. Her very essence leaped off the canvas. She warmed to the eye and her image lingered in the mind.

Thinking of her now, he smiled freely.

‘Amy,’ he murmured.

Her name on his lips was like a song.