Читать книгу Prescription for a Superior Existence - Josh Emmons - Страница 6

ОглавлениеIn this part of the world it is light for half the year and dark the other half. Sometimes at night I look at the halos around the window blinds and breathe in salty air redolent of afternoon trips to the beach I took as a boy, my hands enclosed in my parents’, my feet leaving collapsed imprints in the sand, my mind a whirl of whitewashed images. I remember how the shaded bodies lying under candy-cane umbrellas groped for one another, and how I pulled my mother and father toward the ice-cream vendors, and how I fell in love with the girls who slouched beside their crumbling sandcastles. The sun an unblinking eye on our actions. The waves forever trying to reach us. From the beginning there was so much longing, and from the beginning I could hardly bear it.

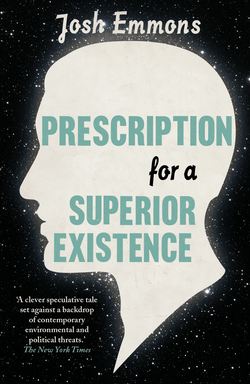

I used to think that with enough scrutiny I would discover a moment to explain what happened later. Not anymore. Now the idea that a Big Bang in my youth caused the events that have sent me here—or that with enough focus I could recall the incident, like an amnesiac witness during cross-examination recollecting how and where and by whom a murder was committed—seems absurd. Now I know that I was always on a collision course with Prescription for a Superior Existence, that it couldn’t have been otherwise.

To pass time I walk around this nightbright Scandinavian village, past seafood grottos and tackle and bait shops and thatched Viking ruins with pockmarked, briny walls blanched the color of dead fish. Bjorn Bjornson, a cod oil wholesaler who joins me sometimes in order to practice his English, though it is already better than most Americans’, says that the village has changed radically since he was young, noting that the citizens didn’t have cellular phones, personal audio devices, satellite receivers, or sustainable fishing laws, that as always in the past many indispensable things did not exist.

He imagines that growing up in California I witnessed even more incredible developments. “Your state is rushing ahead of everywhere else,” he says. “In Europe the conviction is that this is terrible, and we are expected to fear and disdain it. But I have met your countrymen and seen your films and read your literature, and I want to visit to make up my own mind. Consensus is sometimes no more than shared folly.”

Given more time in each other’s company, Bjorn and I might become friends. He is a patient, thoughtful man who considers every angle of a problem without being paralyzed by indecision. If it weren’t dangerous, if information didn’t travel so quickly and unpredictably, I would explain to him why I’m here and ask for his advice; instead I’ve told him I’m a tourist, come to take pictures of the glaciated fjords before they disappear.

And so I have to decide without his or anyone else’s counsel if the past month, and before that all of history, justifies my presence in a remote northern village where it has been decreed that at midnight on Sunday I will, after delivering a eulogy that is both inspirational and absolute, with a solemnity great enough for the occasion, conduct and preside over—I am choosing my words carefully and none other will do—the end of the world.

This is as strange for me to say as it must be to hear, and I should add that I’m not yet certain that the end is coming; it could be a grand deception, or sincerely but wrongly delineated, like the edges of the world on a fifteenth-century map. There are compelling arguments for and against each possibility, and I change my mind about them so often that on Sunday, instead of having discovered the truth, I may be as confused as a pilot with spatial disorientation, in danger of mistaking a graveyard spiral for a safe landing, when up is really down, sky is really earth, and life—suddenly and irreversibly—is really death.