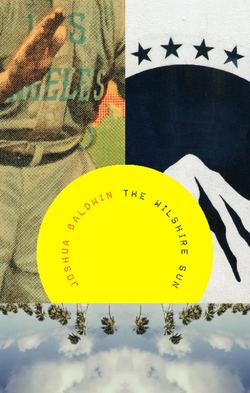

Читать книгу The Wilshire Sun - Joshua Baldwin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

I JUST LANDED IN LOS ANGELES. My older brother has been here two years, in the valley neighborhood of Encino. He makes his living as an importer of flowers, and resides comfortably alone in a one-story cube-shaped house. According to letters and phone conversations he feels “really wonderful.”

I come as a writer, hoping to make a fortune in the movies. Hollywood is hiring these days. That’s what Jerry told me. He’s on his way here right now, some miles behind me (afraid of flying, he chose to take the train). “Come on,” he persuaded me over beers three weeks ago, “we’ll move out there and work together making easy money setting down screenplays both dumb and brilliant.”

When I checked into my apartment building in Santa Monica the fellow at the desk handed me a postcard from Jerry.

Jacob—I’m laid over in a small Arizona town right now, thinking, over a glass of seltzer, why don’t you like my novel? My opinion is that you’re jealous of me. But I am also jealous of you and that complicates the matter. —Jerry

The letter startled me and sent a wave of nausea from my knees to my throat. I entered my room and set my white cap down on the wooden ironing board and stepped onto the little terrace for a cigarette, wondering, was I to consider this a threat from Jerry? And if so, how serious a threat? We met each other through our employ as assistants at a big Manhattan publishing firm. We both hated the day-in-day-out repetitive nonsense of the work, and our friendship, if you could call it that, consisted of complaining about the job in a coffee shop as we ate our egg salad and vinegar sandwiches and pulled viciously at glasses of coke during lunch hour.

I stubbed my cigarette out in an empty almond can, hurried down the dark stairwell of the apartment building and found a corner pay phone to call my brother and let him know that I’d arrived in Los Angeles.

To say the least, I am very excited to be in Los Angeles. Walking down Wilshire Boulevard towards the ocean, the bright sun calming my brain and setting all my spirits at ease, plus the light breeze blowing up my pants-legs; slipping inside the shady newspaper stores, the subdued but also jitterbug delicatessens; even passing the bums smirking into garbage cans and up at the gargantuan traffic lights—all of these things, though I can’t say why, make me feel at home. I’ve never left the East before, and instead of any homesickness, I’ve several times gone so far as to speak aloud to myself today, and to the pigeons as well, “God almighty, this is the place.”

Underneath my intense excitement, I feel an insane sadness, and this too, I love. Somehow, the sadness is filling me with joy. The utter loneliness of the blocks, the long—the endless!—blocks of houses extending north and south, and not a human being on either side except for a tiny faraway mother pushing a baby carriage up her front lawn, the sun hazily illuminating the infinity of the city. Drunk with health, I had to stop once and lean against some shuttered bank to stare across the street at an ancient green clock on the cornice of a building.

I felt real promise in the air this afternoon, and a rush at having disappeared from New York City and its gray, cold, close subway cars, its musty, dim, and crowded living rooms, and its harsh, moronic, tension-filled officebuilding routines of contracts, memorandums, errands, and telegrams.

I came upon a plaza of benches in front of an insurance firm headquarters and was struck with the impression that I’d landed in San Antonio, and scribbled some lousy jokes and bits of dialogue in my pad.

A bunch of palm trees were drooping over my head, filling me with a new desire—like for a new pair of shoes or a chocolate milkshake. I don’t think I want to write scripts with Jerry; I would be better off writing, I think, a simple 200-page novel in my apartment. Listening to the buses swish by, rising early, the pages will definitely pour out of me with great ease.

The trick, of course, is to return to Los Angeles. Five days after my arrival I came down with a terrible fever, and my brother put me on the afternoon train to New York. “Los Angeles is no place for a young man with a fever,” he said to me as he pushed me into my sleeper car. “Now, rest up—here, I’ll close the curtains for you. Mother will meet you at Penn Station.”

In my delirium I supposed my tongue was either missing or up in flames and I made no response to my brother, who appeared to be wearing an apron. Out of a front pouch he pulled a pack of cigarettes and a small jar of instant coffee granules. “For when you’re feeling better, buddy boy,” he said, patting me on my damp head. The last thing I remember of the Golden State is peeking at my brother through the curtains as he dissolved into a shimmering orange grove. I slept deep for three days, until the transfer in Chicago. Now I’m back in Brooklyn Heights, living with my mother and aunt, trying to figure my next move.

When my father killed himself five years ago, my aunt moved in. She helps my mother with the housework and generally tries to cheer her up with fashion magazines, card games, and conversation. Plus she keeps her away from the vodka. She allows her one vice: cigarettes. They smoke together on the stoop. They are sitting down there right now, and their chatter and smoke carries up to my room through the open window. I smoke too, and blow my smoke into their smoke.

I’ve been riding the buses around quite a lot, and going to movies, and eating hot dogs. I keep a large bag of peanuts under my desk. Shells cover the floor of my room. I think I will go to the Paramount building on Times Square tomorrow, for no particular reason. I will have to ride the subway—something I dread.

I took the subway to Grand Central Station, and before walking west to the Paramount building, I sat on a bench in the main waiting hall and drank a cup of watery lunch stand coffee. I stared at a telephone booth and considered calling my brother. I also thought about calling the apartment building in Santa Monica to ask the fellow at the desk if he happened to find a pen somewhere in my room. It seems that I lost my pen in Los Angeles. Or maybe it fell out of my pocket on the train to New York. I don’t know. I liked that pen, a fine Parker Jotter that my father brought back for me from England. He spent three months there about two years before he shot himself, on business—something to do with closing a linen deal with one of the major British retailers, Marks & Spencer I think. Well, I didn’t make any phone calls, and then I looked down at my left tennis shoe and noticed a small tear at the point where the rubber toe meets the canvas, felt depressed, and walked to the Paramount building, where I stopped and looked up at the glittering script on the facade for a few seconds, and then proceeded to the subway and rode back to Brooklyn. I’m going to listen to baseball on the radio now, and try to fall asleep.

I had a dream last night that all different sizes of airplanes were buzzing around in the sky above the harbor. Most of the airplanes were simple silver, but one of them—a huge red and blue jetliner—carried a bunch of bullhorn wielding film directors on the wings. It seems they were directing a complicated scene on the Brooklyn Bridge. All of the cables on the bridge had been removed. I couldn’t understand why there were multiple directors working on the one movie. Maybe some kind of competition was going on. Suddenly, I found myself seated in the cockpit of a rattling bomber, and the pilot told me that at the call of “Action!” I must jump out. He said it would be fine, that I would land in the water. Church bells up the street awoke me, and I went into the kitchen and sat at the table and drank a glass of iced tea.

My mother thinks I should call the publishing firm and ask for my position back. I told her that I’ll be returning to Los Angeles the second week of June (in fact I haven’t made any real arrangements) so there’s really no point. She frowned, and my aunt, glaring at me, took her by the hand and said, “Let him go if he wants to, and besides his brother is there to look after him.”

Then my mother, whimpering, asked me, “Jacob, why don’t you just live with your brother if you really must go back to Los Angeles?”

I told her that if Jerry and I are to collaborate on scripts, we must be in the same neighborhood, and that the valley land is no place for screenwriters. Then my back started to hurt and I felt like screaming so I left the apartment and walked along Columbia Heights, by the water. Across the way, Manhattan was all lit up like a warehouse full of croaking soda vending machines, and the sight did nothing to assuage my impulse to scream—but still I didn’t.

I am trying to determine where my laziness comes from. I’ve concluded that the source must be my grandfather, my mother’s father, a gambling bum who lives in his deceased mother’s apartment on Park Avenue.

I got out of bed this morning at 11:30. From 8:30 on I awoke every half-hour and told myself to get up, but then quickly answered myself with: “No, dreaming is good for writers—it’s the same as writing, really,” and rolled over. An idiotic idea, I recognized when I finally got up and had nothing to show for it, feeling gross and worthless.

But I’ve got to maintain a sense of dignity. So around 1 o’clock this afternoon I took a walk through my neighborhood and down to the piers, bringing along my little pad to take down some story notes. I wish I had an actress friend for whom I could write a script; that would give my project some push. The men up in Paramount would take a look straightaway if they knew the script was attached to one of the rising stars.

Then I recalled how I felt that day sitting under the palm trees in Santa Monica, filled with desire and cool confidence, and I got Chet Baker’s rendition of “Look for the Silver Lining” in my head, and closed my eyes and tried to get to Los Angeles that way. But the moaning foghorns in the harbor prevented any prolonged reverie. I opened my eyes and saw the Staten Island Ferry crashing into the Manhattan slip, and I felt my body shift and knock in sympathy with the event. It’s that game New York plays with natives, the city tells you that every idea you’ve got related to leaving is just a big trap you’ve set up for yourself, that there’s nowhere else to go, and while you may be driven out in disgrace you can’t just willfully depart.

I went to the bank today to check my balances and withdraw some petty cash. When my father died he left me a fair amount of money, just like he did for my mother and my brother, enough to give my own wife and children—should they ever exist—a fine lift. I didn’t think I would touch the money for a long time; after all I’d been working enough to meet all of my modest expenses. Until I quit my job, that is, and went to Los Angeles at Jerry’s urging. And now I’m not working on anything. All I am is a professional dodger, and until I’m back in Los Angeles I don’t see myself making any kind of progress. Once there I’ll start investing in myself, as the saying goes. Here in New York I’m of a mind to go over to my grandfather’s and watch cartoons projected onto his dining room wall (and maybe the ceiling too) and take his pistol out of the bathroom cupboard and shoot at the pigeons congregating in the airshaft.

I went to a 3 o’clock showing of Brass Rain today. The movie opens with a close-up of a brown derby wrapped in blue cellophane, floating in a lagoon. Zooming out, we see the image is inside of a tabloid show on a television mounted high in the ceiling corner at a farmers’ market dining patio. A young man wearing a white flannel suit sits on a metal chair, eating what looks like a fantastic whole-wheat and sugar dusted doughnut. He looks up at the television, and squinting at the derby, removes a pen from the inside pocket of his jacket and scrawls some illegible words on a piece of stationary from the Malibu California Surf Hotel. He waves his hand at a flea, a snare drum cracks, and the title sequence begins, a phantasmagoria of orange-saturated smashed soda bottles, burnt automobiles, and deserted barbershops.

When I got home I took a nap and dreamt that I was sitting by the movie’s lagoon, photographing couples as they rowed around in circles eating tremendous hamburgers with blankets of American cheese drooping out from the bun. Then I was wandering around some French Quarter of Los Angeles, all of the bakers dumping flour off their balconies, and ended up behind the steaming Korean fast food stalls of Wilshire Boulevard. I hurried up when I realized I was on my way to my night job as a tile-scrubber at the Aztec Hotel.

Strolling around Coney Island today, I dropped a coin into a scale to learn my weight: 195 pounds. I looked at my reflection in the protective glass surrounding the bumper car court and was overcome with shame. I am a scruffy faced and plump good-for-nothing. But no! Lo! I’m just an Elvis Presley stunt-double in need of a shower, and I bought a cup of beer, sat down on a bench and watched the women wearing lightweight cardigan sweaters pass by, their breasts pointing out like great torpedoes of life. And I felt a little better, and I walked to the train station and riding home daydreamed about palm trees as I stared at the Statue of Liberty in the distance, from my outlook a mere teal phantom shrouded in smoke. I intend to buy a set of dumb-bells on Fulton Street tomorrow.

I awoke this morning extremely queasy and consumed with the feeling that I am the only person alive—at least on my block. I sat at my desk, lit a cigarette, flipped through my father’s facsimile of the 1860 Leaves of Grass—“afar on arctic ice, the she-walrus lying drowsily, / while her cubs play around;”—and dumped the bit of water remaining in my thermos onto my head. That would be my bath for the day. The cigarette tastes of wet cardboard, I announced to my naked feet. I must get moving, because I have been sitting in my room chewing my lip and turning my head from side to side quite a while now.

These past few days I have been occupied with a new project: writing letters to and from imaginary persons regarding Los Angeles. Some of the correspondents sound fairly insane, their voices echoing with the sort of brighteyed lunacy that I think only Los Angeles allows, like:

To whom it may concern,

And so I spoke, presumably, of laundry, and walked on. Probably on cause of being clean I proceeded to the bar and asked for my keys, then went up to my room to boil an egg. I’m off to Moab tomorrow for the weekend to retrieve a case of vodka from Heck. You come to the party next Saturday at The Terrace in Brentwood, and bring a friend. It will be relaxing, I promise.

Signed,

F. F. Jones

I wish I could have made it to the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles during my truncated stay in town. I went to the library by Prospect Park yesterday and looked at images of the place in a volume called Book Civilization in Los Angeles. I sunk into a pleasant daze for more than an hour, and intermittently recorded this exchange between friends:

Tom,

I saw a great number of women crying today, inside the cars and delis. I notice the women are treated far more poorly here than in New York. I believe my girlfriend in Culver City is afraid of me, because that is a natural feeling towards a fellow here. This is a pretty barbaric place, seems to be dark and late even in the middle of the morning. When will you be coming out? I can set you up in the hills, perhaps; or, if you like, Topanga Canyon where it’s quiet and you could get a screenplay done in a week I bet.

Your pal,

Zev

Zev,

How nice it is nice of you to write, but I don’t think you understand anything about me anymore, not at all. You’re my friend so I imagine you can at least understand that. Here I am in a top-floor stuffy office in the garment district certainly planning my escape from this damned city (if I don’t get out soon they’ll have to give me a cane, and I’m only 32) to come out there to sit poolside and churn out scripts quick as I drink ice whiskey, ice whiskey, ice whiskey. But what with my wife out of work and the babies in need of new clothes I don’t know if I can swing the travel expense. If you could lend me cash for the bus fare I assure you I’ll pay you back. You know I’ll reimburse you fast if you just put me up in Topanga like you say and shut the doors etc.

Take care,

Tom

It seems these imaginary letters summoned an actual letter. I received this from Jerry today:

Jacob,

You really need to come back to Los Angeles. Why not? What happened to you? I found your brother listed in the phonebook and called him up. He told me you came down with a desert fever. Really? Come on. Leave New York before summer strikes in full. Did you catch that movie about the locomotive boom? Just my thing—we could make up something in that style in two days I bet you, with the help of coffee and grilled cheese. I’m not going to wait much longer for you though. I’m at the Hotel Carmel in Santa Monica. Don’t bother responding to this letter. If you’re not knocking at my door smiling by June 15, I’ll assume you’re never coming back. So come on—

Jerry

So it’s take it or leave it, a real ultimatum. I guess Jerry’s right, we could write something pretty funny about a concrete spill on the highway or some terrible door installation mishap, any old thing in the style of the locomotive movie (a basic slapstick whose structure I bet any college educated louse could mimic). Just the two of us in the lobby of the Hotel Carmel, working the thing out like naturals. Intuition!

I went to the Montreal Barber, in the downstairs arcade of the Cities Service Building in Lower Manhattan, to have a crew cut today. Afterwards, walking through the winding, narrow streets of the financial district with so little hair and a brisk wind blowing in from the Atlantic, I got quite chilly and hustled down into the Bowling Green subway station to board an uptown Lexington Avenue express. I wanted to surprise my grandfather with a lunchtime visit. Sadly, the train stalled in the tunnel between the Fulton Street and Brooklyn Bridge stations for about twenty minutes, and I experienced a deep panic. The fairly empty train quickly assumed the atmosphere of a harshly lit and absurdly spacious plastic coffin, and staring at my reflection in the doorway glass I saw my watercolor ghost. A blue light bulb in the tunnel cast a glow inside his left ear, and this served to x-ray his head and reveal a set of pink and green teeth hanging like rotten skin from brown and pimpled gums.

I came to and walked the length of the car back and forth; an old lady knitting a shirt rolled her bespectacled eyes at me, and a khaki-suited banker reading the Sun shook his head and muttered something I took to be: “Stop fucking idiot stop sit Jesus moron subway tonight Christ tomorrow right-now.” But I continued my mad walk in the hopes that my own legs would somehow propel the train, and eventually we did start to move, and I had worked up quite a sweat and my esophagus throbbed, making it hard to swallow even what little was left of my own spittle. I got out at Brooklyn Bridge and walked home, staring down at the wood slat pedestrian walkway (catching glimpses of the river flashing below) the whole way across. I’ll have to postpone the visit to my grandfather’s. Maybe my aunt can drive me over there sometime soon.

The experience on the subway really exhausted me but I didn’t feel like going to bed last night so I bought a crate of Coca-Cola from the Pineapple Street Grocery around 8 o’clock in the evening and drank six bottles through the night. It’s now 7 o’clock in the morning and I’m yet to hit the sack. Sometime in the middle of the night I became very excited and took the jar of instant coffee that my brother gave me down from the small mantel above my bed and threw it at the wall. So now there is a pile of harsh brown sand in the southwest corner of my room, in addition to the peanut shells scattered all around.

Sitting amongst this squalor, I suddenly recall a poster I saw in a hamburger café around Santa Monica Boulevard and 26th that announced “TRY OUR NEW HAMBURGER PEPPER LOAF TODAY!” Hamburger pepper loaf—it has a nice ring to it, but now when I picture the food, a soggy brick of spiced ground round cooked rare, served on a paper plate overwhelmed by the density of the leaking meal, I lose my appetite.

I think I will open an impromptu hamburger stand on our stoop. Maybe I’ll stroll over to the hardware store on Montague Street in a couple of hours and buy a big red and white striped beach umbrella, cook up some patties, and set up shop this evening. It’s Friday, and the drunken couples strolling to the waterfront will likely give in to the temptation.

My aunt, with pronounced reluctance and disgust, agreed to drive me over to my grandfather’s. In an act of passive hostility she drove an extraordinarily roundabout and pothole riddled route through Brooklyn into Queens (the Williamsburg and Greenpoint neighborhoods had apparently experienced a great chemical fire the night before, and many of the synagogues, churches, and warehouses had been reduced to black and blue crutches) and used the Queensboro Bridge to enter Manhattan. The rainy and thick gray mid-afternoon sky filled me with a great lethargy, and I nearly asked my aunt to forget about continuing uptown, she had better just drop me off at the Karen Horney psychiatric clinic that greeted us as we swung off the bridge and slammed onto the pavement of 62nd street. But I stopped myself, and instead, noticing a Chinese takeout restaurant, the Fantasy Wok Palace, I proposed that we stop for a plate of cold noodles with sesame sauce, and maybe even some mixed dumplings. My aunt shook her head and said, “Looking rather fat, you are, young man, let’s better hold off on that now. Besides, I’m sure your grandfather will be spoiling you with cold cuts, butter rolls, and lemonade.”

There were no cold cuts and butter rolls, but there were bottles of beer and a tray of pretzel rods. And sitting in the dining room at the long pinewood table, enjoying the beer and pretzels, I asked my grandfather if he had ever been to Los Angeles. “Well sure,” he told me, “when your greatgrandmother was still alive, a long time ago. It was a different place then—really just a musician’s town, and I rode out there with a musician in fact, a fellow by the name of Timothy Q. Dorothy, a Dixie style drummer. He had some summer employment with a nightclub band out there, and when I saw a poster tacked to the cork board in the mailbox room of this very building that read something like ‘Looking for trip companion to Los Angeles to share driving and gasoline expenses. See Timothy Dorothy in apartment 12G ASAP if interested,’ I went knocking on his door right away, and we made arrangements to leave three days hence. We drove non-stop, switching shifts at the wheel every ten hours, and all we had for food was a great big pail full of sweet corn and several pounds of raisins. I spent that whole summer in Los Angeles, living in a bungalow off Pico Boulevard somewhere in the middle of town. I believe I saw Charlie Chaplin washing his car with a tremendous purple blanket once, and he wasn’t wearing any shirt. I tried to break into the nightclub scene there myself, as a comic, but it didn’t work out and come September I was on the train back to New York City. Why, are you thinking of going?” He must have forgotten I ventured there in April—he’s gotten quite senile with certain things.