Читать книгу Making David into Goliath - Joshua Muravchik - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеtwo

The Arab Cause Becomes Palestinian (and “Progressive”)

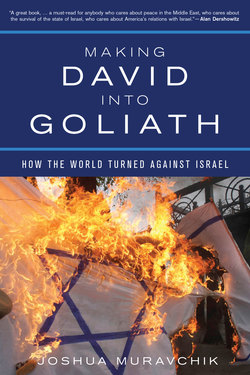

Israel would never again enjoy the degree of sympathy it experienced in 1967. The simplest reason was that Israel would never again seem so endangered. The devastating prowess demonstrated by Israel’s fighting forces gave it an aura of invulnerability.

The implications of this new image were compounded by another transformation resulting from the war. Until 1967, Israel was pitted against the Arabs, who held an advantage in terms of population of roughly fifty to one, and in terms of territory of more than five hundred to one, as well as larger armies and more wealth and natural resources. The Six Day War, however, set in motion a redefinition of the conflict. No longer was it Israel versus the Arabs. Now it was Israel versus the homeless Palestinians. David had become Goliath.

The altered perspective that made Israel look big instead of small was accompanied by a shift in ideological appearances that was no less important. The Arab states were seen as autocratic and reactionary. But, the groups that came to speak for the Palestinians presented them as members of the world’s “progressive” camp.

These twin transformations stemmed from the crystallization of the idea of a Palestinian nation in the second half of the twentieth century. The absence of a widespread sense of Palestinian nationhood before then may surprise those who came to the “Mideast conflict” in the 1970s or later, when Palestinian national aspirations came to be seen as the quintessence of the principle of self-determination. But, in historical context, it is easy to understand. Most of the countries of the Middle East, with Egypt the most notable exception, were modern creations—their borders drawn by colonial rulers—and the development of their national identities works in progress. And so it was with Palestine, except that there the process was strengthened by the presence of a hated enemy against whom the Palestinians could define themselves and make their cause sacred to their brother Arabs.

Traditionally, most of the people in the region identified themselves simply or primarily as Muslims. Indeed, strong traces of this legacy are still evident among Palestinians. As recently as 2011, according to the Palestinian press agency, WAFA, a survey revealed that when asked their first identity, 57 percent of Palestinians answered “Muslim,” rather than “Palestinian,” “Arab,” or “human being.”1 Of course, by the same token, some people in the West might feel that Christianity is their first attachment, but it is likely that the proportion is much smaller. More to the point, “Christian” is a spiritual identity, not a political or ethnic one. For Islam, these two selves are not separable. When Palestinians were asked in the same poll to choose the political system best for themselves, a plurality of 40 percent favored an Islamic caliphate, whereas only 24 percent wanted “a system like one of the Arab countries” and 12 percent “a system like one of the European countries.”

Beyond religion, another strong affinity that came before nationalism was pan-Arabism—the idea that all Arabs should form a single polity. This vision had germinated in the years after World War I in reaction to the high-handedness with which the Western powers carved up the Arab lands they had taken from Turkey. Pan-Arabism was central to the philosophy of the Baath movement that took power in Syria and Iraq in the 1960s. But its foremost proponent was Gamal Abdel Nasser, the most popular figure that the Arab world has known since the crusades.

Pan-Arabism was not so natural to Egypt, with its distinct and ancient national identity, as to the newly minted Arab countries. Nonetheless, it answered the burning need to restore dignity by creating a union strong enough to stand up to the West and to Israel. “Lift your head, brother, the days of humiliation are over,” was one of the slogans of Nasser’s revolution. As the Cambridge History of Egypt summarizes it:

Arab unity, under Egyptian leadership, would guarantee victory over the Zionist enemy and the liberation of Arab land; [and] battling Israel was only the local facet of a struggle that set the Arabs in general, and particularly Egypt, against imperialism . . . and through which the connection with the third world was established.2

Although today there is not much left of this ideology, for the two decades bracketed by the 1948 and 1967 Arab–Israel wars, pan-Arabism was the dominant political idea of the Arab world. Given the salience of Muslim and Arab identities, Palestinian identity lagged far behind.

Palestine, after all, had never been a country. The name designated a portion of the Arab territory taken from the defeated Ottomans in World War I and given to the British to govern as a League of Nations “mandate,” meaning they were not to treat it as a colony. The Balfour Declaration reflected an awareness of the Arab inhabitants without seeing them as a distinct nationality. Rather, it spoke of the Jewish people and “existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” Likewise, a full generation later, the UN partition plan of 1947 referred to creating “Arab and Jewish states . . . in Palestine.” The numerous other diplomatic documents of the preceding decades spoke in similar terms. Insofar as anyone referred to “Palestinians,” the term simply meant those who dwelled in the territory called Palestine, Jews as well as Arabs, without any suggestion that these individuals constituted a distinct political or cultural community as is connoted by the word “nation.”

It was Zionism, itself—made to seem real and threatening by the Balfour Declaration—that stimulated the Arabs of Palestine to search for their own identity. They first turned their gaze northward. Palestine had been connected with, or part of Syria, virtually since its earliest identity in the form of the second century Roman province called Syria Palaestina. “When Amir Faysal established a government in Damascus in October 1918, the Palestinian Arabs’ aspirations focused on him,” writes Ann Mosely Lesch, coauthor of a Rand Corporation study of Palestinian nationalism. “An all-Palestine Conference in February 1919 . . . supported the inclusion of Palestine in an independent Syria.”3

Faysal’s ouster by France was not fatal to his ambitions for a throne—he went on to become king of Iraq—but it eliminated this option for the Palestinians. So, in 1921, local Arab notables formed an alternative program to present to London. It sought cancelation of the Balfour Declaration, an end to Jewish immigration, restoration of Ottoman law, and agreement that “Palestine not . . . be separated from the neighboring Arab states.”4 It also called for the election of a representative government in Palestine, but this was less an expression of national identity than simply a demand for self-rule within the jurisdiction designated as “Palestine” by the reigning powers. The essential sensibility was not Palestinian, per se, but rather the feeling, as the Rand study puts it, “that Palestine is essentially Arab and that it should be governed by Arabs.”5

The same sentiment motivated the Arab Higher Committee (AHC), which was formed in 1936 and led by Haj Amin al-Husseini, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and president of the Supreme Muslim Council. Spearheading the Arab revolt against the Jews and British from 1936 to 1939, the AHC spoke in the name of the Arabs of Palestine but did not call itself “Palestinian.”

During the 1948 war over the birth of Israel, al-Husseini declared the formation of a government of all Palestine. But Alain Gresh, former editor of Le Monde Diplomatique and a sympathetic authority on the Palestinian cause, observes that “this appears to have been much more an Egyptian maneuver intended to counter Hashemite designs [the Hashemites were the rulers of Transjordan] than a desire to nurture an embryo Palestinian government. This government was soon forgotten.”6

Egypt came away from the 1948 war occupying Gaza, which had been part of Palestine. In the 1950s, tiring of al-Husseini and his AHC, Nasser directed the creation of some new Palestinian offices. But “Nasser was . . . concerned not with forming a provisional government . . . of a future independent state . . . only with creating a sort of Palestinian body [as] the spokesman for Cairo’s policy,” explains another French specialist, cited by Gresh, who adds: “At this time, the question of the Palestinian people and its self-determination and independent struggle was not an issue either for Nasser or the Arab Higher Committee. This view was, with some nuances, shared by the Palestinians themselves.”7

This picture began to change in 1964 at the first Arab League summit meeting, convened in Cairo by Nasser, at which the decision was made to create the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The PLO would eventually become the very embodiment of Palestinian national aspirations, but this is not how it began. As scholar Hussam Mohamed put it:

Regardless of the claim that the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1964 was necessary to fill a gap in the political life of the Palestinians, the new organization was the stepchild of inter-Arab rivalries and power politics. In fact, it was President Nasser of Egypt who, during the 1964 Arab Summit Conference, recommended the creation of the PLO, and nominated [Ahmad] Shuqairy to be its first chairman. . . . The . . . goals of the new Palestinian organization were simple: . . . to cater more to the interests of certain Arab states than to those of the Palestinian people.8

Ahmad Shuqairy was born in Lebanon but his family home was in the ancient city of Acre on the Mediterranean coast just north of Haifa. His father, As’ad, was an Ottoman official, cool to the cause of Arab, much less Palestinian independence.9 But, Ahmad made a career as an Arab spokesman. In the 1940s, he worked for al-Husseini’s AHC until becoming, in 1949, a member of Syria’s delegation to the United Nations. He followed that with seven years of service as assistant secretary-general of the Arab League and then several years back at the United Nations, this time representing Saudi Arabia until 1963, shortly before Nasser tabbed him to found the PLO.10 In short, he was the very personification of pan-Arabism.

Shuqairy was a man of bombast who won few admirers. Conor Cruise O’Brien, who represented Ireland in the United Nations during Shuqairy’s tenure there as the Saudi ambassador, preserves this memory:

All delegates are constrained in the General Assembly to become connoisseurs of windbags, and [Shuqairy] was, by common assent, the windbag’s windbag. He used to begin his oratorical set piece each year with the words: “I am honored to address the members of the United Nations”—pause for effect—“all [x] of them.” X always represented whatever the real current membership was, minus one. Israel was a non-nation.11

Years later, Yasser Arafat offered his take on Shuqairy to biographer Thomas Kiernan. “The appointment of [Shuqairy] to speak for the cause of liberation was a clear reflection of Nasser’s contempt for our cause. . . . It was obvious from the beginning that the PLO was to be nothing but . . . a tool of the Egyptians to keep us quiet.”12

Shuqairy personally crafted the Palestinian National Charter adopted in 1964. Abdallah Frangi, a Palestinian leader, calls it a landmark “which for the first time formulated the ideas of a Palestinian identity.”13 Nonetheless, its “most striking feature” to Gresh was “the absence of all reference to any sovereignty either of the Palestinian people or of the PLO, or to a Palestinian state.” Gresh attributes this in part to the pressures of Arab governments and in part to “Arab nationalism [which] was still heavily predominant.”14

But Arab nationalism, or pan-Arabism, soon had the stuffing knocked out of it by Israel in the 1967 war. When, on the morrow of the defeat, Nasser tendered his resignation, crowds gathered in Egyptian cities—whether spontaneously or orchestrated by his henchmen, most likely some of each—to demand he remain in office, which he did until dying of a heart attack in 1970. By then he had lost much of his stature, and the pan-Arab philosophy that he had championed was moribund.

Its demise made room for individual nationalisms, especially that of the Palestinians. Such a movement already existed in embryonic form. In the 1950s, in Egypt, a group of students with Palestinian backgrounds had begun to forge a path different from the one laid down by Nasser and the other Arab rulers. They were angry at the manipulation of the Palestinian issue by the Arab governments that, with the partial exception of Jordan, refused to absorb the Palestinian refugees, preferring to keep them in UN-run camps as a symbol of the Arab cause. And yet these same governments seemed in no hurry to vindicate that cause by facing Israel on the battlefield. Thus, believing themselves to be the only ones who cared truly and deeply about Palestine, these young men formed tiny cells, determined to take the fight into their own hands.

In 1959, in Kuwait where many of them had migrated since its oil boom generated an abundance of jobs, several of these tiny groups came together to form the Palestinian Liberation Movement. Its initials, read backward, spelled the Arabic word for conquest: Al Fatah. They established a periodical, Filastinuna, meaning Our Palestine.15 When the PLO was founded five years later under Nasser’s aegis, Fatah viewed it as a rival.

Fatah’s leader was a thirty-year-old activist who called himself Yasser Arafat. Born in Cairo in 1929, where his family had moved from Jerusalem a couple of years earlier, Arafat’s full name was Abd al-Rahman Abd al-Rauf Arafat al-Qudwa al-Husseini. The nickname, Yasser, means “easygoing,” which seems not entirely apt for a man who told his most credulous biographer, Alan Hart, that he worked “between 18 and 19 hours a day . . . 365 days a year.”16

According to some biographers, he was a distant cousin on his mother’s side of the Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, whereas others say it was on his father’s side, or not at all.17 Whatever the exact relationship, most versions agree that during his political maturation Arafat was involved with Husseini and his AHC.18

This is a sensitive question because of al-Husseini’s intimate alliance with Hitler, which has been amply documented despite the disingenuous claim of Arafat’s deputy, Salah Khalaf, known as Abu Iyad, that “anyone who knew him personally, myself included, knew” al-Husseini was no “Nazi sympathizer.”19 But, however much Arafat may have looked up to al-Husseini, there is no evidence he shared the older man’s proclivity for Nazism which was a spent force by the time Arafat came of age.

Rather, Arafat’s own youthful affinity was with the Muslim Brotherhood. His biographers, Andrew Gowers and Tony Walker, write:

Arafat was drawn to the Brotherhood’s militant doctrines of anti-imperialism and national revival through Islam. It remains a moot point whether Arafat was actually a member or merely a sympathizer—he insists now that he was never a member—but he drew heavily on Ikhwan [Brotherhood] support in student elections at King Fouad I University . . . and subsequently in elections for the Palestinian Students’ League.20

Gowers and Walker speculate that the time Arafat spent in an Egyptian jail in 1954 was part of a crackdown on the Brotherhood, which had helped Nasser to reach power but then fell out with him violently.21 And they postulate that the connection between Arafat and the Brotherhood helped to bring support to Fatah from Saudi Arabia relatively early.22 In a like vein, Arafat chose the nom du guerre, Abu Ammar who, he explained, had been “captured, tortured to force him to give up his faith and finally put to death by the infidels. . . . the first martyr of Islam whose name became the symbol of total fidelity to one’s faith and beliefs in the Arab world.”23

Yet, Arafat himself was apparently somewhat casual in observing the rituals of Islam. Arafat’s fawning authorized biographer, Alan Hart, quotes Um Jihad, wife of Arafat’s deputy, Abu Jihad, as explaining that Arafat “always prays in the morning and usually he gathers the fives times a day into one.”24 But, however observant he may have been, Arafat’s connection to his religious roots was important to his success and that of Fatah. Other Palestinian armed groups tended to secularism. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and two of its splinters, the PFLP-General Command and the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PDFLP), were Marxist or Marxist-Leninist. The leaders of the PFLP and the PDFLP and a large share of the members of all three groups were Christians. Two other groups, As-Saiqa and the Arab Liberation Front, were closely tied, respectively, to the strenuously secular Baathist governments of Syria and Iraq. Within Fatah, some of Arafat’s closest collaborators were also Marxists, but other leaders, including Arafat, were not. The genius of Fatah was that its only cause was Palestine. Individual members could lean left or right, but Fatah was a single-issue group. And Arafat’s success as a leader owed much to the fact that he embodied this undeviating focus.

This is not to say that in these early years he or Fatah envisioned a Palestinian state. Rather, its original purpose was simply to build an independent Palestinian fighting organization to spearhead the Arab struggle. The pan-Arabists, they said, who claimed that Arab unity was the route to liberating Palestine had it backward: the liberation of Palestine would pave the way to Arab unity. The exact configuration of Arab rule over the area could be determined once the Zionist interlopers had been expelled.

Fatah’s ambiguity about a Palestinian state was evident as late as 1968 when, having largely taken over the PLO, it reaffirmed the provision of the 1964 Palestinian National Covenant written by Shuqairy that said:

The Palestinian people believe in Arab unity. In order to contribute their share toward the attainment of that objective, however, they must, at the present stage of their struggle, safeguard their Palestinian identity and develop their consciousness of that identity.25

Although the idea of Palestinian statehood still developed only gradually, Arafat’s Fatah was more earnest and effective than Shuqairy’s PLO at fostering a national identity. And Fatah’s philosophy of guerrilla struggle gained salience even with Nasser after the Arabs’ 1967 defeat.

At the Khartoum summit of Arab leaders convened in August 1967 to discuss a response to their military debacle, Shuqairy’s star was in obvious descent. Although the war tarnished all Arab leaders, Shuqairy suffered particular humiliation for having forecasted, with characteristic bombast, that “no Jew will remain alive.” Such statements, it was recognized in the postmortems, had deeply damaged the Arab cause.

“The PLO was not even mentioned in the . . . final communiqué,” at Khartoum, observes the Israeli expert Moshe Shemesh, and “the fidai [guerrilla] organizations became undisputed rulers in the Palestinian arena.”26 They might have simply pushed the PLO aside but, instead, with Nasser’s help, they took it over and made it their own. A few months after Khartoum and a day after meeting with one of Nasser’s aides, Shuqairy submitted his resignation, to be replaced as chairman by Yahya Hamouda, a neutral figure.27 During the course of 1968, Fatah and the other armed groups largely gained control of the various bodies of the PLO, and by 1969 Hamouda gave way to Arafat.

Leaving behind the bombast of Shuqairy as well as the pro-Nazi heritage of Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Arafat-led PLO rapidly won a place for itself in the diffuse global revolutionary Left. As early as 1962, Arafat and other top Fatah leaders had visited Algeria, whose successful guerrilla war for independence from France offered a model and inspiration. One of the group, Abu-Jihad (the nom de guerre of Khalil al-Wazir), stayed on to open the PLO’s first foreign office.28

The Algerian example proved to be crucial. The independence movement there had triumphed more in the political plain than the battlefield. Mohammed Yazid, who had served as the new government’s minister of information, shared the lessons with Fatah. Portray the enemy as not only Israel but also “world imperialism,” he counseled, and “present the Palestinian struggle as a struggle for liberation like the others.”29

“The others” meant Communists as well as various movements around the globe professing a less orthodox anti-capitalism or fighting to be free of colonial rule. It would be some years before Moscow would open its arms to Fatah, but the non-European Communists were more receptive. Algeria provided entrée to the most important of these regimes—China, North Vietnam, and Cuba. Arafat and Abu-Jihad visited China in 1964, and the latter went on to North Vietnam.30

Beijing began to provide material aid to Fatah, and the group issued a series of pamphlets titled, The Chinese Experience, The Vietnamese Experience, The Cuban Experience, etc.31 The admiration of the Fatah leaders seems to have been genuine. Abu Iyad relates that on one of several subsequent visits:

I was extremely impressed by the Chinese people’s dedication. They seemed totally devoted to labor—manual or intellectual—and spent their leisure time in simple and healthy activities. Their life-style seemed characterized by a Puritanism worthy of the most fundamentalist Islam. “The Prophet couldn’t have done better than Mao Zedong,” I remarked to Arafat.32

Abu Iyad also found Cuba intoxicating. The “Cuban intelligence” official who greeted him on arrival was a “wonderfully humorous man,” and Fidel was a “veritable force of nature . . . plain-speaking . . . earthy and vibrant.”33 The most important model, however, was North Vietnam, which was accumulating sympathizers worldwide for its long-odds war against America. “The Vietnamese resistance . . . filled me with a sense of hope,” said Abu Iyad. “Everything I was to see in North Vietnam was a source of enrichment and inspiration for me.”34

Thus did Fatah (and the PLO under Fatah’s leadership) master a lingo that lifted their struggle out of the reactionary Arab past and imbedded it instead in an international movement of “progressive” forces. A seven-point program adopted by Fatah’s central committee in January 1969 declared: “The struggle of the Palestinian people, like that of the Vietnamese people and other peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, is part of the historic process of the liberation of the oppressed peoples from colonialism and imperialism.”35

In contrast to Abu Iyad, who was held spellbound by every Communist state he visited, Arafat maintained his ties with the religious and conservative side of the Arab world, never squandering the patronage he assiduously cultivated of the Saudi royals or the other dynasties of the oil-favored Gulf. Nonetheless, he could channel Das Kapital and the holy Koran with equal conviction. “Our struggle is part and parcel of every struggle against imperialism, injustice and oppression in the world,” he affirmed. “It is part of the world revolution which aims at establishing social justice and liberating mankind.”36

So central was the Vietnamese model to the new persona of the Palestinian movement that forty-odd years later, long after the end of the Cold War, and with Hanoi straining to import large elements of free enterprise into its economy, Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas, was still singing the praises of Vietnam’s Communist revolution. During a 2010 visit to that country he averred:

[W]e are comrades in struggle and fighting, and our vision of the future is one. Historically, people have always linked Palestine and Vietnam, and to this day, when people mention the Palestinian struggle they recall the struggle of the Vietnamese people. We have both suffered occupation, colonialism and oppression, but you eventually prevailed, and we are certain that, thanks to your position and your support, we shall prevail as well.37

By 1968, with the PLO now in Fatah’s hands, a new revolutionary identity established, its relations blossoming with Beijing, Hanoi, and Havana, and the whole arrangement blessed by Nasser, Arafat found that Moscow was ready to open its arms. Nasser included him in his entourage on a visit to the USSR, using a pseudonym identifying him as an Egyptian so as to conceal him from the West. That year, the Soviet press began to liken Fatah to the heroic “partisans” of World War II, and Moscow arranged for some of its East European satellite states to supply it with weapons.38 In 1969, the Kremlin formally recognized the PLO as a legitimate “national liberation movement,” and Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin hailed its “just national liberation and anti-imperialist struggle.”39

More important even than the arms and training that the Soviet connection provided were the political benefits. “To recruit the Soviet Union as a sponsor was undoubtedly a great coup for Arafat, because its worldwide propaganda services [were put] at his disposal,” comments journalist David Pryce-Jones.40 The Soviet Union’s state news agencies, like the newspaper Pravda and the news service TASS, might have had little international credibility, but Moscow nonetheless influenced discourse outside its own precincts through a network of front groups and sympathizers and the contacts with respectable journalists cultivated by Soviet personnel in many fields and guises.

The strategy of embedding itself in the global revolutionary Left inspired the PLO to adopt a new statement of the goals and purposes. This was unveiled by Abu Iyad at a Beirut press conference in October 1968. “I announced,” he wrote, “that our strategic objective was to work toward the creation of a democratic state in which Arabs and Jews would live together harmoniously as fully equal citizens in the whole of historic Palestine.”41

The import of this new approach was explained by Arafat biographers Gowers and Walker:

Gone, said Fatah, were the old chauvinist slogans about revenge and “throwing the Jews into the sea” that had been the stock and trade of Shukairy’s generation of leaders . . . Instead, the Palestinians were now proposing to co-operate with those Jews who had been prepared to throw off the shackles of Zionism in building a completely new society.42

In a later interview with Gowers and Walker, Abu Iyad added this gloss: “In itself this was saying something revolutionary at the time as far as Arabs were concerned: that we were willing to live with the Jews in Palestine.”43

Enduring the presence of some Jews, “revolutionary” though this idea may have been, did not imply acceptance of the existence of Israel. On the contrary, Fatah’s manifesto of October 1968, explained: “Our struggle aspires to liberate the Jews themselves . . . [O]ur revolution, which believes in the freedom and dignity of men, considers first and foremost . . . the radical uprooting of Zionism and the liquidation of the conquest of the Zionist settlers in all forms.” In other words, after the “liquidation” of Israel, the Jews could live on as a minority in Arab Palestine, where they could enjoy the same “dignified life . . . they had always lived under the auspices of the Arab state.”44

And even this dubious honor was not offered to all the Jews of Israel, but only, according to the Palestinian covenant, those “Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist invasion.” The “Zionist invasion” was defined in other Fatah documents as having commenced in 1917 with the Balfour Declaration. In other words, those who had arrived before 1917, and perhaps their descendants, could stay on as citizens of “democratic Palestine.” The overwhelming majority of Israeli Jews would, however, have to leave. Boiled down, this differed little from Shuqairy’s threat to drive them into the sea, but it sounded better.

Nor was this Arab state that the PLO envisioned intended to be “secular” although the phrase “democratic, secular state” came into circulation and was commonly attributed to the PLO. Gresh reports:

Contrary to a widespread notion, the idea of a democratic state is not associated with the idea of a secular state in Palestinian political thought. In fact, the idea of a secular state does not appear in any of the PLO’s official texts of this period nor in those of Fatah or any other organization, although it can be found in one or two declarations.45

As Bernard Lewis catalogued at the time, the constitution of almost every Arab state, including those that had come under the rule of revolutionary parties professing “secular” ideologies, proclaimed Islam to be the “state religion” or the “religion of the state.”46

The emphasis was on “democratic,” but this was not meant in the sense in which the term is used in the West. The “democratic” countries after whom the PLO intended to model its state were the ones over which Abu Iyad gushed: the People’s Republic of China, North Vietnam, and Cuba.

If the “democratic, secular state” was intended neither to be democratic nor secular, in the normal meaning of those terms, neither was it clear, for that matter, that it would long be a state. As late as 1971, Nabil Sha’ath, a top Fatah official, rebutted charges from left-wing groups within the PLO that Fatah had abandoned pan-Arabism, by reiterating Fatah’s original view of the relation between the Palestinian and the broader Arab cause. “We see the Palestinian state as a step towards federation,” he insisted.47

If there was, in short, more packaging than substance in the new vision that Arafat and his fellows were proffering; it nonetheless sufficed to put the Palestinian cause in good standing with the revolutionary Left. When, in 1969, some hundred-and-fifty young Europeans traveled to a Middle Eastern training camp to prepare themselves to enlist in revolutionary struggles, Palestinian liberation was among the designated causes.48 That same year, a time of extreme radical agitation among Western youth, a bomb was planted in the communal hall of West Berlin’s Jewish congregation. The authors of the act left a flyer decrying “the Left’s continued paralysis in facing up to the theoretical implications of the Middle-East conflict, a paralysis for which German guilt feelings are responsible.” It went on:

We admittedly gassed Jews and therefore feel obliged to protect them from further threats of genocide. This kind of neurotic backward-looking anti-Fascism, obsessed as it is by past history, totally disregards the non-justifiability of the State of Israel. True anti-Fascism consists in an explicit and unequivocal identification with the fighting fedayeen.49

Also that year the journal Free Palestine exulted: “[Al Fatah] has certainly been able to achieve a breakthrough in what used to be a Zionist domain: the Western leftist movements. Al Fatah has become to many synonymous with freedom fighting and an expression of struggle against oppression everywhere.”50

Of course, the revolutionary Left occupied only a corner of the Western political scene. But, even if marginal, it was in much better odor than the fascist Right that had once constituted the European allies of the Arab leadership. Hitler’s collaborator, al-Husseini, had continued to represent the Palestinian Arab cause into the 1960s, and the propaganda offices of Nasser’s government employed several escaped officials of the Nazi regime. This may have explained some of the self-defeating over-the-top rhetoric that helped to put the Arabs at a disadvantage in the contest for international sympathy.

Now, however, a critical makeover had been achieved. No longer did Israel enjoy the public relations gift of opponents who were collaborators of Hitler and Goebbels; now they faced the comrades of such chic, romanticized figures as Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara. Not only had David become Goliath, but on the other side the frog had become a prince.

This transformation reshaped the view of the conflict not only in the eyes of the international Left but to some extent in the mainstream. For example, TIME, whose reportage cum commentary had been warmly pro-Israel in 1967 to the point of endorsing the retention of territories Israel had captured, now ran a cover story on Al Fatah. The headline, “The Guerrilla Threat in the Middle East,” sounded negative, but the body of the article was admiring:

With the fanaticism and desperation of men who have nothing to lose, the fedayeen have taken the destiny of the Palestinians into their own hands. . . . In the aftermath of the Arab defeat, the fedayeen are today the only ones carrying the fight to Israel. The guerrillas provide an outlet for the fierce Arab resentment of Israel and give an awakened sense of pride to a people accustomed to decades of defeat, disillusionment and humiliation. In the process, the Arabs have come to idolize Mohammed (“Yasser”) Arafat, a leader of El Fatah fedayeen who has emerged as the most visible spokesman for the commandos.51

In the battle for the hearts and minds of the rest of the world, the Arab side had taken, to borrow a phrase from the PLO’s new hero, Chairman Mao, a great leap forward.