Читать книгу Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion Picture - Joshua Levine - Страница 10

Survival

ОглавлениеIn the early summer of 1940, Anthony Irwin was a young officer in the Essex Regiment. As his battalion carried out a fighting retreat towards the French coast, held up by civilian refugees, targeted by guns and aircraft, pressured by approaching German infantry, Irwin, like most of his fellow officers and men, was experiencing war for the first time.

One afternoon, under attack from German bombers, he saw his first dead bodies. The first pair upset Irwin – but the second pair made him vomit, and appeared in his dreams for years afterwards. The difference was not in the manner of their deaths or even the severity of their wounds. It was in the second pair’s ‘indecent attitude’. Naked, demeaned, bloated and distorted, they embodied something worse than death.

That evening, his battalion was under attack again. Overwhelmed, a young private began crying. Irwin took the boy aside, intending to lead him away. But the private, rigid with misery, refused to move. The only thing to do, decided Irwin, was to knock him out. He ordered a sergeant to take a swing at the private’s chin – but the sergeant missed, cracking his knuckles on a wall. The private suddenly came to life and ran, but was chased down by Irwin who tackled him, and punched him in the face. The boy was now unconscious.

Irwin slung the private over his shoulder and carried him down to a nearby cellar. It was dark inside, and Irwin shouted for somebody to bring him a light. In the relative quiet, Irwin heard surprised voices, a man’s and a woman’s, and his eyes slowly focused on a soldier in the corner of the cellar having sex with a Belgian barmaid. Who could blame them, wondered Irwin. With death so close, they were grabbing hold of life.

Irwin was among hundreds of thousands of officers and men of the British Expeditionary Force retreating through Belgium towards the coast. They had sailed to France following the declaration of war on Germany on 3 September 1939. After months of ‘phoney war’, the German Blitzkrieg in the west had been launched on the morning of 10 May, and the bulk of the British forces was hurried into Belgium to assume prearranged positions along the River Dyle. There they formed the Allies’ left flank, alongside the French and Belgian armies, facing Hitler’s Army Group B. Further to the south, the Allies’ right flank was protected by the mighty Maginot line, a series of heavily defended fortresses, blockhouses and bunkers along the French border with Germany.

For a few short days in May 1940, the Allies and the Germans, broadly equal in military terms, seemed destined to act out another war of trenches and attrition. If experience could be trusted, the Germans would soon be hurling themselves at heavily defended Allied lines.

But the Allied commanders were instead offered a sharp lesson in modern warfare. Between the strongly held Allied flanks was the Ardennes forest, theoretically impregnable, and weakly defended by the French; only four light cavalry divisions and ten reserve divisions protected a hundred-mile front. And the Germans had a plan to exploit this front.

First formulated by Lieutenant General Erich Manstein, the plan had been through seven drafts by May 1940. It involved an initial attack on Holland and northern Belgium, drawing the Allies into a trap. For at the same time, the main German attack would come further south at the very weakest point of the Ardennes front. Led by Panzer tank divisions, it would begin by crossing the River Meuse, pushing through the area around Sedan and surging north-west for the coast, splitting the French armies in two and joining up with the northern attack to encircle the British Expeditionary Force.

The Manstein Plan was extremely risky; breaking through a wooded area was a huge logistical challenge, and the Panzer tank was a largely untested weapon. The plan’s success depended on unprecedented speed and intensive air support, but, above all, it depended on surprise. If the French learned of it in advance, it would surely fail. In January 1940, however, the Belgians had captured a copy of the previous German plan – to launch the main assault in Holland and Belgium. This was a straightforward repeat of Germany’s First World War strategy – and the Allies had no reason to believe that the Germans were now considering an alternative.

The level of risk involved in the Manstein Plan was so great, the break from traditional practice so complete, that most German generals refused to countenance it. It gained, however, an influential supporter in General Franz Halder, Chief of Staff of Army High Command. And, crucially, it had the support of the man whose opinion ultimately mattered in Nazi Germany – Adolf Hitler. The attack was ordered to go ahead.

In the event, the French were taken by complete surprise. Armoured forces, spearheaded by Lieutenant General Heinz Guderian’s Panzer Corps and devastatingly supported by the Luftwaffe, plunged through enemy lines, tearing a massive hole in French defences. German tanks began to race through France unchallenged. This is why, just days after taking up their positions in Belgium, British soldiers – clearly able to hold their own against the Germans – were being ordered backwards. There must, they thought, be a localised reason. Had the Germans broken through in a nearby sector? Or was their particular battalion being sent to the rear for some misdemeanour?

At first, British units retreated in stages, from one defendable line to another. Sometimes an entire division was pulled out, free to plug a distant gap. As the retreat gathered pace, confusion increased, and rumours began to circulate. One of these rumours proved true – an almighty breakthrough to the south was threatening to outflank the British army. But for most of the retreat there was no suggestion of evacuation, nor mention of the now legendary name Dunkirk.

All sorts of soldiers found themselves on the move, from elite guardsmen to untrained labour troops. Some went on foot, marching in battalion strength or stumbling alone. Others travelled in trucks, on horses, tractors and bicycles. One intrepid group was observed riding dairy cattle. Under fire and lacking supplies, the men of the British army were in every kind of physical and mental state.

One man, Walter Osborn of the Royal Sussex Regiment, was in a particularly difficult situation. Having sent the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, an anonymous letter asking for ‘some leave for the lads’, he had been sentenced to forty-two days’ detention for using ‘language prejudicial to good order and conduct’. He was now engaged in a fighting retreat with his comrades – but he was at a disadvantage. Whenever the fighting stopped, he was locked up in a nearby barn or cellar to continue serving his sentence. This did not seem fair. As he complained to a regimental policeman: ‘A man’s got a right to know where he stands!’

Even more unusual was the small soldier sitting in a truck on the road to Tourcoing. In steel helmet and khaki greatcoat, carrying a rifle, the soldier looked like any other. The uniform may have hung a little, but that was hardly unusual. Private soldiers weren’t expected to dress like Errol Flynn in The Charge of the Light Brigade. The odd thing about this soldier was her marriage to a private in the East Surrey Regiment.

The soldier was Augusta Hersey, a twenty-one-year-old French girl. She had recently married Bill Hersey, a storeman in the 1st East Surreys. They had met in Augusta’s parents’ café when Hersey was stationed nearby, and despite neither speaking a word of the other’s language, they had fallen in love. Hersey had asked Augusta’s father for her hand by pointing at the word mariage in a French–English dictionary and repeating the phrase ‘Your daughter …’

Hersey was fortunate to have a sentimental company commander who agreed – against any number of regulations – that Augusta could dress in army uniform and retreat with his battalion. This was how the couple found themselves, almost together, fleeing the German advance. But their retreat had no definite objective until Lord Gort, the British commander, reached the brave conclusion that the only way to save a percentage of his army was to send Anthony Irwin, Walter Osborn, and the rest of the British Expeditionary Force, towards Dunkirk, the one port still in Allied hands, from where some of them could be hurriedly transported home by ship.

As they arrived at Dunkirk, soldiers were confronted by an unforgettable scene. Captain William Tennant, appointed Senior Naval Officer Dunkirk by the Admiralty, sailed from Dover to Dunkirk on the morning of 27 May to coordinate Operation Dynamo. He entered a town on fire, its streets littered with wreckage, every window smashed. Smoke from a burning oil refinery filled the town and its docks. There were dead and wounded men lying in the streets. As he walked on, he was confronted by an angry, snarling mob of British soldiers, rifles at the ready. He managed to defuse a difficult situation by offering the mob’s ringleader a swig from his flask.

Another naval officer arrived in Dunkirk two days later. Approaching from the sea, he was struck by one of the most pathetic sights he had ever seen. To the east of the port were ten miles of beach, the entire length blackened by tens of thousands of men. As he drew closer, he could see that many had waded into the water, queuing for a turn to tumble into pitiable little boats. The scene seemed hopeless. How, he wondered, could more than a fraction of these men hope to get away?

Yet the closer one came to the beaches, and the more time one spent on them, the clearer it became that there was no single picture and no single story. An officer of the Royal Sussex Regiment recalls arriving on the beach, and being smartly saluted by a military policeman who asked for his unit before politely directing him into a perfectly ordered queue. A young signalman, on the other hand, was greeted with the words, ‘Get out of here before we shoot you!’ in another queue. And a Royal Engineers sergeant watched a swarm of desperate soldiers fighting to get onto a boat as soon as it reached the shallows. In a desperate attempt to restore order before the boat capsized, the sailor in charge drew his revolver and shot one of the soldiers in the head. There was barely a reaction from the others. ‘There was such chaos on the beach,’ remembers the sergeant, ‘that this didn’t seem to be out of keeping.’

For every individual who stood on the beach or on the mole (the long breakwater from which most troops were evacuated), or retreated clinging to a cow, there was a different reality. Set side by side, these realities often contradict each other. To take one element of the story – the beaches covered a large area, they were populated by many thousands of people in varying mental and physical states over nearly ten intense days of rapidly changing conditions. How could these stories not contradict each other? The whole world was present on those beaches.

And the reality was no tidier once the soldiers were on boats and ships sailing for Britain. Bombed and shot at by the Luftwaffe, shelled by coastal batteries, fearful of mines and torpedoes, the men might be on their way to safety – but it had not yet arrived. An officer in the Cheshire Regiment was one of thirty aboard a whaler being rowed from the beach to a destroyer moored offshore which would then ferry them home. As the whaler drew close, the destroyer suddenly upped anchor and headed towards England. Overcome by emotion, an army chaplain leapt up in the whaler and yelled, ‘Lord! Lord! Why hast thou forsaken us?’ As he jumped, water began to pour into the boat, and everyone simultaneously screamed at him. Seconds later, in answer to his prayer – or possibly in answer to the exceptionally loud noise just made by thirty men – the destroyer turned round and came to pick them all up.

In the event, the vast majority of the British Expeditionary Force was brought safely home from Dunkirk. Most of those were carried by naval ships or large merchant vessels; the famous little ships (some crewed by ordinary people, most by sailors) were mainly used to ferry the soldiers from the shallow beaches to the larger ships moored offshore. But had these soldiers been killed or captured, Britain would surely have been forced to seek a peace settlement with Hitler, history would have taken a far darker course, and we would all be living in a very different world today.

This helps to explain why Dunkirk – a disastrous defeat followed by a desperate evacuation – has come to be seen as a glorious event, the snatching of victory from the jaws of a worldwide calamity. Whereas Armistice Day and most other war commemorations are sombre occasions focusing on loss, Dunkirk anniversaries feel more like celebrations, as small ships recreate their journeys across the Channel. Dunkirk represents hope and survival – and this is what it represented from the very start.

When the evacuation began, so dire was Britain’s military situation that, as in Pandora’s Box, only hope remained. On Sunday 26 May, a national day of prayer was observed. Services in Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral were mirrored in churches and synagogues across Britain, and in the London Mosque in Southfields.

In his sermon, the Archbishop of Canterbury asserted that Britain both needed and deserved God’s help. ‘We are called to take our place in a mighty conflict between right and wrong,’ he said, suggesting that Britain’s moral principles were invested with sanctity because ‘they stand for the will of God.’ God was with Britain, and He alone knew how the evil enemy would be beaten. It is little wonder that the evacuation, quickly dubbed miraculous by Winston Churchill, assumed a quasi-religious quality. The Archbishop had been right, it seemed, Britain was favoured by the Lord. This confirmed the views of such writers as Rupert Brooke and Rudyard Kipling, and it helped give rise to a concept that has survived the last seven and a half decades: Dunkirk Spirit.

Defined as the refusal to surrender or despair in a time of crisis, Dunkirk Spirit seems to have asserted itself spontaneously. As they arrived back in Britain, most soldiers saw themselves as the wretched remnants of a trampled army. Many felt ashamed. But they were confounded by the unexpected public mood. ‘We were put on a train and wherever we stopped,’ says a lieutenant of the Durham Light Infantry, ‘people came up with coffee and cigarettes. We had evidence from this tremendous euphoria that we were heroes and had won some sort of victory. Even though it was obvious that we had been thoroughly beaten.’

Nella Last was a housewife from Lancashire. In early June she wrote in her diary:

This morning I lingered over my breakfast, reading and rereading the accounts of the Dunkirk evacuation. I felt as if deep inside me was a harp that vibrated and sang … I forgot I was a middle-aged woman who often got tired and who had backache. The story made me feel part of something that was undying.

The emotional outpouring did not please everybody, however. Major General Bernard Montgomery, commander of 3rd Division during the retreat, was disgusted to see soldiers walking around London with an embroidered ‘Dunkirk’ flash on their uniforms. ‘They thought they were heroes,’ he later wrote, ‘and the civilian public thought so too. It was not understood that the British Army had suffered a crashing defeat.’ A German invasion was expected, and exhibitions of pride and self-congratulation did not sit well with Montgomery. But for the majority, while Britain still had a fighting chance of survival, the returning soldiers were glorious heroes.

Some civilians baulked at the euphoria too. An old woman watched the shattered troops disembarking at Dover on 3 June. ‘When I was a girl,’ she said, ‘soldiers used to look so smart and would never have gone out without gloves.’ The Mass Observation reporter to whom she spoke noted a flat, unemotional atmosphere in the town. ‘I can only describe it,’ he wrote, ‘as no flags, no flowers and unlike the press reports.’

However widely felt, the authorities were keen to encourage the sense of emotion and relief – and this was something that Winston Churchill understood instinctively. Oliver Lyttelton, later to be a member of Churchill’s War Cabinet, describes great leadership as the ability to dull the rational faculty and substitute enthusiasm for it. In 1940, on a careful evaluation of the odds few would have acted decisively. But despite not being the cleverest of men, Churchill had the ability to inspire the country. He made you feel, says Lyttelton, as though you were a great actor in great events.

On the evening of 4 June, radio listeners heard a report of the Prime Minister’s speech, given earlier in the day to the House of Commons. The speech did not attempt to ignore reality; Churchill spoke of the German armoured divisions sweeping like a scythe around the British, French and Belgian armies in the north, closely followed by ‘the dull brute mass’ of the German army. He spoke of the losses of men and the overwhelming losses of guns and equipment. He acknowledged that thankfulness at the escape of the army should not blind the country ‘to the fact that what happened in France and Belgium is a colossal military disaster’.

But Churchill also described ‘a miracle of deliverance, achieved by valour, by perseverance, by perfect discipline, by faultless service, by resource, by skill, by unconquerable fidelity’. If this is what we can manage in defeat, he was suggesting, imagine what we can achieve in victory! He then spoke of his confidence that Britain would be able to defend itself against a German invasion:

We shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender …

Inspiring though these words must have sounded (the front page of the next morning’s Daily Mirror barked ‘WE NEVER SURRENDER’), they hint at a difficult future. Fighting in streets and hills implies guerrilla warfare: the sort of fighting to be engaged in once the Germans had already gained a foothold in Britain. Beyond this, though, Churchill was implying that Britain had strength in reserve. And while this might serve as a reassurance to her own people it was also meant as a message to the United States. We will hold the fort, Churchill was saying, until you come and join us. But please don’t wait too long …

Joan Seaman, a teenager in London, remembers being scared in the aftermath of Dunkirk. But when she heard these words, the effect was transforming. ‘When people have decried Churchill, I’ve always said, “Yes, but he stopped me being afraid!”’ George Purton, a private in the Royal Army Service Corps, had just struggled back from Dunkirk. He could not share Churchill’s opinion of the evacuation, but he knew ‘a splendid bit of propaganda’ when he heard it.

The next evening, 5 June, another BBC broadcast boosted the nation. Novelist and playwright J. B. Priestley gave a talk after the news. It was much chummier than Churchill’s, delivered as though knocking back a drink in the saloon bar with friends. In his Yorkshire accent, Priestley mocked the typical Englishness of the Dunkirk evacuation, the miserable blunder having to be retrieved before it was too late. He sneered at the Germans: they might not make many mistakes, but they didn’t achieve epics either. ‘There is nothing about them,’ he said, ‘that ever catches the world’s imagination.’ Warming to his theme that the British are lovable, absurd and quixotic, he spoke of the most ‘English’ aspect of the whole affair: the little pleasure steamers called away from their seaside world of sandcastles and peppermint rock to a horrid world of magnetic mines and machine guns. Some of the steamers had been sunk. But now they were immortal: ‘And our great grandchildren, when they learn how we began this War by snatching glory out of defeat, and then swept on to victory, may also learn how the little holiday steamers made an excursion to hell and came back victorious.’

In Priestley’s talk – and in other reactions to the evacuation – pride can be sensed in perceived British traits: modesty, comradeship, eccentricity, a belief in fairness, a willingness to stand up to bullies, and an effortless superiority. One does not, after all, want to be seen trying too hard. As Kipling once wrote:

Greater the deed, greater the need

Lightly to laugh it away,

Shall be the mark of the English breed

Until the Judgment Day!

The emerging story of Dunkirk was being shaped to fit the sense of national self. When, after all, had a plucky little army last hurried towards the French coast, desperate to escape an arrogant and vastly more powerful enemy, only to succeed against the odds and fight its way to freedom? During the Hundred Years War, of course, when the English won the glorious Battle of Agincourt, fought, according to Shakespeare, by the ‘happy few’, the ‘band of brothers’. If a sense of English self had been born at Agincourt, the Dunkirk story needed very little shaping.

Prevailing public attitudes can be gauged by the reaction to a play that premiered two weeks after the evacuation. Thunder Rock, starring Michael Redgrave, opened at the Neighbourhood Theatre in Kensington. Its author, Robert Ardrey, described it as a play for desperate people – and it was an instant hit. Theatre critic Harold Hobson recalls that it had the same effect on its audience that Churchill’s speech had on his. It proved so popular that it was secretly bankrolled by the Treasury and transferred to the West End – emphasising the blurred line between spontaneous spirit and its imposition by the authorities.

The plot revolves around a journalist, disillusioned by the modern world, who has retreated to a solitary life on a lighthouse on the American lakes. There he is visited by the ghosts of men and women who drowned on the lake a century earlier as they headed west to escape the problems of their own times. As the journalist and the ghosts speak, the parallels become clear; just as they should have engaged with the problems of their age, so should he now do the same. He resolves to leave the lighthouse and rejoin the wartime struggle. In a closing monologue, he rehearses the issues so relevant to the modern audience:

We’ve reason to believe that wars will cease one day, but only if we stop them ourselves. Get into it to get out … We’ve got to create a new order out of the chaos of the old … A new order that will eradicate oppression, unemployment, starvation and wars as the old order eradicated plague and pestilences. And that is what we’ve to fight and work for … not fighting for fighting’s sake, but to make a new world of the old.

Such lofty social ambitions reveal how Dunkirk Spirit was mutating. The initial sense of relief (that defeat was not inevitable) and pride (in an epic last-ditch effort) was combining with political realities to become something more complex and interesting. If Adolf Hitler was a symptom rather than a cause of the problem, then with victory must come a better and fairer world.

But for all the words spoken and written, perhaps Dunkirk Spirit’s most impressive manifestation was in the realm of British industry. In the immediate aftermath of the evacuation, the need for greater industrial effort was fully acknowledged by workers. This rare convergence of management and workforce, reflecting a shared interest in survival, was perhaps the apex of Dunkirk Spirit. At the SU factory in Birmingham, responsible for building carburettors for Spitfire and Hurricane fighters, output was doubled in the fortnight after Dunkirk. Official working hours stretched from eight in the morning to seven in the evening, seven days a week – but many workers stayed at their benches until midnight and slept on the factory premises. Such a state of affairs would have been unimaginable at almost any other time in the last century.

When the Blitz – the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign against Britain – seized the country for eight and a half months between September 1940 and May 1941, ‘Dunkirk Spirit’ and ‘Blitz Spirit’ merged into a single idealised mood, the indiscriminate bombs emphasising the need to pull together. But the essence of both was the instinctive realisation that life truly mattered.

In the immediate post-war years, the concept of Dunkirk Spirit was sometimes called upon to decry the supposed British trait of trying hard only when something becomes necessary, but more recently, it has been used in its earliest, simplest sense. In December 2015, for example, retired picture framer Peter Clarkson pulled on a pair of swimming trunks and went for a swim in his kitchen after heavy rains flooded his Cumbria home. ‘This is how we treat these floods!’ he shouted as he breast-stroked past the cooker, explaining that he was trying to ‘gee up the neighbours with a bit of Dunkirk Spirit’. And when Hull City made a winning start to the 2016–17 Premier League season despite injuries to leading players and the lack of a permanent manager, midfielder Shaun Maloney ascribed results to ‘Dunkirk Spirit’ at the club.

But Dunkirk Spirit reached its high water mark during the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign, when the country was almost overwhelmed by references to the period. As Peter Hargreaves, a leading donor to the ‘Leave’ campaign, urged the public to vote for Brexit, he harked back to the last time Britain left Europe. ‘It will be like Dunkirk again,’ he said. ‘We will get out there and we will become incredibly successful because we will be insecure again. And insecurity is fantastic.’ Nigel Farage, meanwhile, not satisfied with invoking Dunkirk, tried to restage it by sailing a flotilla of small ships up the Thames, bearing slogans like ‘Vote Out and be Great Britain again’.

But these are the words and actions of people in current situations, with modern agendas. How do veterans of the evacuation describe Dunkirk Spirit? What did – and does – it mean to them?

For the most part, they relate it to their individual experiences. Robert Halliday of the Royal Engineers arrived in France at the start of the war and was evacuated from Bray Dunes on 1 June. As far as he is concerned, the essence of Dunkirk Spirit was the units of British and French soldiers fighting fiercely on the Dunkirk perimeter. ‘The guys who were keeping them [the Germans] at bay and letting us through were as good as gold!’ he says. He recalls soldiers calling out as he passed – ‘Good luck, off you go!’ His eyes sparkle as he remembers these events. Dunkirk Spirit remains very real to him. It was, he says, ‘wonderful’. George Wagner, who was evacuated from La Panne on 1 June, relates Dunkirk Spirit to survival. ‘We wanted to survive as a country. It was about comradeship and everyone together helping.’

Not everybody agrees. Ted Oates of the Royal Army Service Corps was rescued from the Dunkirk mole. Asked if Dunkirk Spirit means anything to him, he simply shakes his head. And far from experiencing Dunkirk Spirit, George Purton feels that the British army was effectively betrayed. ‘We were sent into something,’ he says, ‘that we couldn’t cope with.’ He remembers Dunkirk as a time of isolation. ‘There was so much happening and you were concerned about yourself only. How the hell am I going to get out of this?’

Dunkirk holds a semi-sacred place in Britain’s collective conscience. It has spawned conflicting experiences and attitudes. It inspires strong emotions, not only among veterans but in those born years afterwards, with only a folk memory of the event and a politically convenient interpretation. How then does a modern filmmaker approach it?

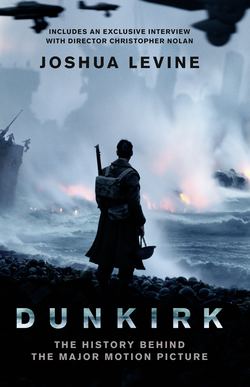

Chris Nolan, one of the most respected directors currently working, has written and directed a feature film set during the evacuation. It was a story with which he was already familiar. ‘I think every English schoolboy knows it,’ he says. ‘It’s in your bones, but I thought it was time to go back to the original source.’

Reappraising the Dunkirk story, Chris built up questions about what had really happened. ‘I was assuming, as modern, cynical people do, that when I looked into it, what I would find would be disappointing. That the mythology of Dunkirk Spirit would fall away and there would be a more banal centre.’ But as he unpeeled the layers, he found something unexpected: ‘I realised that the simplifications actually expose a truth, because the bigger truth, the wood for the trees, is that an absolutely extraordinary thing happened at Dunkirk. I realised how utterly heroic the event was.’

Heroic – but not straightforward. ‘When you dive into the real life of the story, what it would really have been like to be there, you find that it’s an incredibly complicated event. The sheer numbers of people involved – it was like a city on the beach. And in any city, there is cowardice, there is selfishness, there is greed, and there are instances of heroism.’ And the fact that heroism occurred alongside negative behaviours, that it flourished in spite of base human nature, makes it all the more affecting and powerful. ‘That,’ says Chris, ‘is what true heroism is.’ Yet for all the individual acts, he sees the Dunkirk evacuation as a communal effort by ordinary people acting for the greater good. This, he says, makes the heroism greater than the sum of its parts. And it is ultimately his reason for making the film.

Another attraction is the sheer universality of the story. ‘Everybody can understand the greatness of it – it’s primal, it’s biblical. It’s the Israelites driven down to the sea by the Egyptians.’ This offers an ideal background for what he calls ‘present-tense characters’, anonymous individuals without unwieldy back stories. ‘The idea is,’ he says, ‘that they can be anonymous and neutral, and the audience can encounter them, and become wrapped up in their present-tense difficulties and challenges.’

Chris sees himself as proxy for the audience while making the film. ‘What I’m feeling and how I choose to record what I’m feeling – the way in which I’m acquiring the shots – fires my imagination about how to put the film together.’ If he has a visceral reaction, he feels he’s on the right track. ‘I’m sitting in the cinema watching it as I shoot it,’ he says. And for him, to tell the story well it has to be shot from the point of view of the participants – on land, in the air, and at sea. Which means that on the little ships, almost all of the shots he eventually used are from the deck, while on the aircraft, cameras are carefully mounted in places where the audience can see what the pilot sees. ‘You want things to feel real, and you want them to be experienced. Pure cinema, to me, is always a subjective experience.’

The enemy barely makes an appearance in the film. German soldiers appear only very briefly, and even then the audience barely sees their faces. But this, as Nolan points out, reflects the reality of the situation, the subjective experience of the men on the beach. ‘When you look at first-hand accounts, close contact with the enemy was extremely sporadic for most British soldiers. I wanted to put the audience in the boots of a young inexperienced soldier thrown into this situation, and from the accounts, they did not stare into the eyes of Germans. I wanted to be true to that and embrace the timeless nature of the story. The reason the story has sustained generations of interpretation and will continue to do so, is because it’s not about the Germans and the British, it’s not about the specifics of the conflict. It’s about survival. I wanted to make it as a survival story.’

In fact, the actual enemies of most of the British soldiers (at least those not defending the Dunkirk perimeter) were aeroplanes, artillery guns, submarines, mines and gunboats. And a battle against an unseen enemy that can’t be fought, touched, or often even seen, creates an unusual war film. In fact, in Chris’s eyes, it is not a war film at all. ‘It’s more of a horror than a war film. It’s about psychological horror, about unseen threats. The guys on the beaches had very little understanding of what was happening and what would happen – and I want the audience to be in the same position.’

Another enemy was time. ‘It is the ultimate race against time,’ he says. ‘But set against that, you have the length of time of the event, comprising boredom, stasis, things not happening. They’re stuck and this is where the tension comes from, where the adrenalin comes from. Making a film about people standing in line on a bridge to nowhere, time becomes everything.’

Chris Nolan may want his audience to feel as baffled and uninformed as the young men queuing under fire for a place on a boat home, but as the author of a history book on the same subject, I do not. I want to paint a vivid picture of the event, offering readers rather more clarity than two soldiers offered Pilot Officer Al Deere of 54 Squadron after he had crash-landed on the beaches on 28 May:

‘Where are you going?’ asked Deere.

‘You tell us,’ said one of the soldiers.

‘You’re evacuating, aren’t you?’

‘We don’t know.’

Before examining what happened, though, I want to place the event in its historical context, and so it is important to find out more about the lives of young people in the years leading up to the war. What, we will ask next, did it mean to be young in an age of uncertainty? Where did Dunkirk come from?