Читать книгу Beauty and Atrocity: People, Politics and Ireland’s Fight for Peace - Joshua Levine - Страница 4

1 THE STRANGER

ОглавлениеIn the autumn of 2008 I flew into Belfast to begin a journey. I had little idea where it would take me, although I knew that its first night would be spent in the Madison Hotel on Botanic Avenue. As I stood at the airport baggage carousel, I was nervous. I had never been to Northern Ireland before, and I decided that I ought to have a first impression, so I began to pay deliberate attention to everything around me. In the end I needn’t have worried because my first actual impression almost overwhelmed me. The taxi driver taking me into town asked my name and, within a beat of my reply, asked whether I was ‘a Jew’. I said I was. ‘My son’s name is Reuben,’ he said. ‘He sounds like more of a Jew than you.’ I had absolutely no idea what to say. ‘The Catholics are anti-Semitic, they support the PLO,’ he continued, ‘but I’m a Presbyterian and we like you.’ He assured me that I had nothing to worry about because, when Christ comes again, the Jews are going straight to heaven. If I wanted to understand more, then I should visit an Orange Lodge. On he went, as though sent by the Tourist Board to give me an unforgettable first impression. Eventually, with a smile and a handshake, he dropped me outside the hotel.

I was in Belfast to try to discover what the Troubles had been about. I wanted to find out the history behind them, and in order to do that I wanted to meet the people who had lived through them, those who had suffered, and those who had caused the suffering. I wanted to know why people had behaved as they did, how representative they had been, and whether they now try to justify their actions. And I wanted a sense of the future, of whether Northern Ireland is moving beyond the Troubles. And so here I was, ten minutes into my journey, with lots of questions, and a place in heaven to look forward to.

I have a particular memory of the Troubles. Bombs and bullets did not affect me in any real way, but it is a memory worth recounting because it mirrors the experience of many who lived in London during the Seventies and Eighties, for whom the Troubles were always in the background. On a summer’s afternoon in 1982 I was at home, wearing a green football shirt and gloves. I cleared some space on the floor, took down a picture, and started throwing a ball against the wall, diving to save it as it came back. I would play like that for hours, but on this particular day I was interrupted by a loud noise. Half a mile away, in the Inner Circle of Regents Park, a bomb planted underneath a bandstand blew up. In that moment seven people were torn to pieces.

I knew the bandstand very well. My father would take my sister and me to sit in deckchairs by the lake, where we would listen to brass bands playing funny mixes of military marches and West End show tunes. And now the masked bogeymen of the Provisional Irish Republican Army had decided to kill the performers – who had been in the middle of a medley from Oliver! – in front of people like us who’d come along to listen. According to a member of the audience, ‘Suddenly there was this tremendous whoosh and I saw a leg fly past me. The bandstand seemed to lift off and I could see bandsmen flying through the air. For a moment I could not believe it.’ I had not witnessed the bomb, but I can remember the bleakness and confusion that it conjured up. Who in the name of God had done this and why?

As the years went by, I, like almost every other English person, became very familiar with reports of the Troubles in the papers and on the news. But the sensible questions never seemed to be asked. The reports all blended into one another, leaving me with a tired stream of images so clichéd they sometimes bordered on the comic. I got to know men in bowler hats marching down streets, men in balaclavas firing over coffins and men with dubbed voices defending the latest outrage, but I had no context for these people, no real sense of them. I never noticed any genuine discussion about what they were fighting for, or how the situation might be resolved. Bombs and death just seemed to be things that happened over there and sometimes over here. The media seemed to want us to believe that Northern Ireland was populated by two kinds of people: bigots and psychopaths. If the real attitudes and beliefs of the people of Northern Ireland were ever reported – as they must have been – they certainly never filtered through to me. I cannot have been the only person in Britain to have been left in the dark about a subject that was never out of the news. Now I wanted to find out more.

As I was to discover, I had not been alone in my ignorance. The British government had very little sense of historical context when it sent its troops into Northern Ireland in August 1969. The arrival of its soldiers, in response to escalating violence, marked the start of the government’s active participation in the Troubles, and represented an unusually vigorous British reaction to an old problem. For the first fifty years of Northern Ireland’s existence, the British government had kept the province at arm’s length. Northern Ireland was given its own parliament at Stormont, to set policy on internal matters, allowing Whitehall and Westminster to remain in the background. One little Home Office unit might cast an occasional glance towards Ulster, but the unit’s importance can be gauged by the fact that it was also responsible for the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man, and the state licensing system in Carlisle. According to Ken Bloomfield, the retired head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service, there were times when the government was less in touch with what was happening in its own province ‘than it was with what was happening in Gambia or Outer Mongolia’.

In 1970 Reginald Maudling, the British Home Secretary, boarded a plane bringing him home from Northern Ireland with the words, ‘For God’s sake, someone bring me a large scotch. What a bloody awful country…’ He gasped for a drink because he simply did not know what do about the essential problem of Northern Ireland, a problem that still exists today: the province is populated by two distinct groups. The overwhelmingly Protestant unionists consider themselves British and want the north to remain part of the United Kingdom. The overwhelmingly Catholic nationalists consider themselves Irish and want the north to become part of a united Ireland. A unionist might speak of ‘Northern Ireland’, a loyal province of the United Kingdom, and a nationalist might speak of the ‘six counties’, an arbitrarily displaced chunk of the Irish nation; but they are both referring to the same piece of land of 5,452 square miles, roughly half the size of Wales.

Back in the Seventies and Eighties I would probably not have heard the terms ‘unionist’ and ‘nationalist’ as often as the terms ‘loyalist’ and ‘republican’. Broadly speaking – because these definitions are subjective – republicans are those who have supported the use of force to create a single independent Irish republic, while loyalists are grass-roots unionists, many of whom have supported the use of force to maintain the union with Britain.

When I arrived in Belfast the Good Friday Agreement was a decade old and the Troubles appeared to be over. But several months later Northern Ireland was reminded of what it had been missing. On the evening of Saturday, 7 March 2009 two pizza delivery men arrived at the Massereene army base in the town of Antrim. Four soldiers came out to the main gate to meet them. As the pizzas were handed over, gunmen in a nearby car opened fire with semi-automatic rifles, leaving all six men lying on the ground. The gunmen stepped out of their car, moved forward and opened fire again, before driving away. Two of the soldiers were killed. The other two soldiers and the delivery men, both Polish immigrants, were wounded. ‘For the last ten years,’ said Ian Paisley Jr. of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), ‘people believed things like this happened in foreign countries, places like Basra. Unfortunately, it has returned to our doorstep.’ Responsibility for the attack was claimed by the Real IRA, a group of dissident republicans who had broken away from the Provisional IRA in 1997. Shortly after the murders at the Massereene barracks a policeman was shot dead in Craigavon by the Continuity IRA, another dissident organization which had broken away from the Provisional IRA, back in 1986. These attacks were intended to provoke a reaction from loyalist paramilitaries, to reignite the tit-for-tat killings that characterized thirty years of the Troubles, to force the British to bring soldiers back onto the streets of Northern Ireland, and to reawaken the war. The overwhelming majority of people in the north, including most of those for whom violence was once a way of life, are keen to see that the dissident republicans do not get their wish.

Northern Ireland has changed a great deal since the days of violence – but Belfast remains a city with a grim reputation to overcome. Paul Theroux, writing in 1983, was not seduced: ‘I had never imagined Europe could look so threadbare – such empty trains, such blackened buildings, such recent ruins. And bellicose religion, and dirt, and poverty, and narrow-mindedness, and sneaky defiance, trickery and murder, and little brick terraces, and drink shops, and empty stores, and barricades, and boarded windows, and starved dogs, and dirty-faced children – it looked like the past in an old picture.’

And if this is how it was to visit, how much worse to live in the place? A local man told me of a drive south along the Ormeau Road in the late Seventies. He passed a building standing on its own, while those on either side lay in ruins. ‘Look at that!’ he remembers saying to his wife, ‘How has that building escaped the bombs?’ When he drove back up the road a few hours later, it was gone. Yet even during the bad times, when the evenings saw the city’s streets empty, pubs deserted, and restaurants closed, there were visitors to Belfast who could see beyond the obvious. ‘It’s a charming port, one of the world’s great deep water harbours, cupped in rolling downs on the bight of Belfast Lough,’ wrote the often acerbic P. J. O’Rourke in 1988. He admired the buildings too: ‘The city is built in the best and earliest period of Victorian architecture with delicate brickwork on every humble warehouse and factory. Even the mill hand tenement houses have Palladio’s proportions in a miniature way.’

The port, the linen mills, the rope works, tea-drying, whisky and tobacco manufacture: these were the foundations of Belfast’s once great civic pride. Walking around the city today, that pride hangs on in the self-conscious grandeur of the neo-classical buildings, the immensity of the Laganside cranes, the self-assurance of Queen’s University, the extravagance of the Grand Opera House, and the dignity of the figures that stand in front of City Hall, embodying hard work and learning. Modern Belfast may not be a beautiful city, but it has nothing at all in common with the war-torn nightmare that sent Theroux scurrying on to his next port of call. While it may mourn the loss of its industrial strength, it has welcomed peace, and it is trying to create an identity for itself. It is busy and vibrant, a collection of areas rather than a unified whole, not yet sure whether it will be a city built around its specifics, or an urban mess of shopping malls and car parks. Its restaurants, clubs, hotels, and cafés are unself-consciously appreciated. People in Belfast speak to you, they are friendly, city dwellers without the sneer. Perhaps that’s because in Belfast you can exist in two worlds at once, staring out over Cave Hill as you wait for a bus in the centre of town. It does not take long to escape into the hills, where generations of Belfast children have played at being soldiers.

It doesn’t do, however, to overstate the affability. While I found people from Belfast (Belfasters? Belfastians?) friendly and keen to talk entertainingly on all manner of subjects, I encountered wariness too. Of course I did. I was writing a book. I was a busybody, and an English busybody at that. Northern Ireland people have had every reason to be wary over the last few decades. As Seamus Heaney warned in the title of his 1975 poem ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’, saying the wrong thing to the wrong person could have dangerous consequences. As I settled into my journey, befriending strangers and begging interviews, encounters that began warmly could sometimes chill, as though I had stepped across an invisible line. A lot of the time that line should have been perfectly obvious. Once, standing about with a group of republicans, all of them friendly and chattering away, I asked a question about a particular man. I asked whether he had ever come under suspicion as an informer. It was a foolish, foolish question. For all I knew, he could have been a personal friend of everybody in the room. For all I knew, he could have been in the room. Everyone stopped speaking, and my legs gave way a fraction. ‘Be very careful…’ said one man, before repeating the warning twice. It was a lesson in Northern Ireland etiquette.

On another occasion somebody said of me, ‘He knows more than he’s letting on.’ I’m still not entirely sure what the man meant, but I suppose he was suggesting that I might be working for the secret services. Once I was actually told by a republican that I’d been ‘vetted’ but it was all right, because I wasn’t a ‘spook’. When I asked him how he could be so sure, he smiled. The fact is that Belfast is a complicated but friendly place. Hospitable too. I was bought many drinks and cooked many meals by people who weren’t flush with money. And if there was suspicion based on my English accent, or the level of interest I was taking, well, how could it be any other way in a place where informers are still reporting back to handlers? In the wake of the March 2009 killings the authorities were quick to reassure the public that the dissident groups were well infiltrated. And people have not forgotten about men like Robert Nairac, an undercover army officer who was killed in South Armagh in 1977 while pretending to be a Belfast republican. He raised suspicions by asking questions in a pub. An English stranger asking questions can still raise suspicions.

Belfast may have an impressive industrial heritage (after all, its yards built the Titanic and the Olympic), it may be strikingly situated, and it may be friendly, but these things are not what the city is known for today. It is known for its Troubles, its murals of gunmen and hunger strikers, and the great iron curtain that separates its communities, euphemistically described as the ‘Peace Walls’. And no matter how much a visitor has read about this peculiar divide, it still comes as a shock to find the Catholics of the Falls Road and the Protestants of the Shankill Road living mutually exclusive lives, so close to one another.

It is difficult not to encounter striking images in the city. Walking around the ‘interface’ area of Ardoyne in north Belfast, I looked into a Catholic back garden backing onto a Peace Wall. The wall consists of ten feet of concrete, ten feet of steel, and thirty feet of wire-mesh fence on top. And there, in this cramped garden at the base of the wall, sits a well-used child’s trampoline and a tiny washing line. If, in years to come, a museum of the Troubles is opened, the curators could do worse than to recreate this tableau in the entrance hall. On the other side of the wall lies a similar garden and a similar house, in a different world. Re-reading this paragraph, I see that it contains the phrase ‘a Catholic back garden’. In Belfast a square of paving can have a religion.

But just as things that would be normal to a local person strike a visitor as odd, so the opposite is true. Taking a bus tour of the city, the guide pointed out the Royal Victoria Hospital, where, he gushed, ‘Not only do Catholic and Protestant doctors work together, but for years they have treated Catholic and Protestant patients side by side.’ In a world where segregated housing and education still exist, an integrated hospital passes for a tourist attraction.

To visit the interface areas of Belfast is to enter a world of frontier-like alertness. These were the paramilitaries’ breeding grounds. I went to the Shankill Estate, a collection of grey, two-storey, postwar terraced houses, set around a grassy central area. I was taken there by a Catholic taxi driver who fidgeted nervously as we walked around. A few years ago, he said, he would never have dared come here, as we would have been challenged within seconds of our arrival. But things have changed. The Shankill Estate is now on the visitor’s map. This is partly because of its edgy association with violence, but mainly because of its murals. They are painted on the gable ends of the terraces, and they represent scenes and individuals from mythology, history, and the very recent past. There are the paramilitary crests of the UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force) and the UDA (Ulster Defence Association), Union flags, and masked gunmen pointing their rifles directly at the tourist. There are men in sashes and bowler hats, demanding the right to march. There is the face of Oliver Cromwell, with, in capitals, a quote attributed to him: ‘Catholicism is more than a religion. It is a political power therefore I’m led to believe that there will be no peace in Ireland until the Catholic Church is crushed.’

There is a massive photograph, transposed onto a wall, of ‘Military Commander Stevie “Top Gun” McKeag, 1970–2000’, who wears a backwards-facing baseball cap, an earring, and a thick gold chain. Stephen McKeag was a young man responsible for the killing of Philomena Hanna, a Catholic woman serving behind the counter of a pharmacy on the nearby Springfield Road. McKeag entered her shop, fired at her until she fell, and then fired into her head as she lay on the ground. Today, according to the mural, McKeag is ‘sleeping where no shadows fall’.

One of the murals particularly caught my eye. It depicts a rock by the sea, on which sits a severed hand, oozing blood. In the background a hairy warrior stands on the prow of a ship, one hand in the air, as though he has just thrown something. Where his other hand should be is a bloody stump. The painting represents the story of the Red Hand of Ulster, of which there are several versions. In one, there is no rightful heir to the throne of Ulster, so the High King of Ireland suggests a boat race across Strangford Lough and whoever reaches the far shoreline first will be crowned king of Ulster. The race begins and one man, O’Neill, falls behind, but he has an idea. As his rival is about to reach the shore, he hacks off his own hand and hurls it onto the land. He wins the race and becomes king. In another version of the story the handless man isn’t Irish at all; he is a Scot named MacDonnell. So the legend of the Red Hand has been used to support contrasting claims to the province. It has been present on loyalist paramilitary crests and on the official Ulster flag, but it has also appeared on the uniforms of the republican Irish Citizen Army, founded in 1913, and on badges of the Gaelic Athletic Association. It is now predominantly associated with unionism and loyalism, but it is an emotive symbol that has crossed the divide. Which is interesting – because the story of the Red Hand represents a state of mind that spans the divide. It is the story of a man who wants Ulster so badly that he is willing to cripple himself in order to lay his claim.

The confrontational style of the Shankill murals reflects the attitudes of the Shankill people. The area has the nervous energy of a pioneer post. Protestants may be in the majority in Northern Ireland, but they have always been a minority on the island of Ireland, and their 400-year fight for survival is the key to their identity. A British army officer, serving in Belfast in the early Seventies, told me of walking past a statue of William III with the slogan ‘This we will maintain’ carved on its base. He stopped a Protestant man and asked him, ‘What will you maintain?’ and was told, ‘I don’t know – but we’ll maintain it.’ Nowadays, wandering around the city centre, the visitor might feel a sense of faded unionist pride, but on the Shankill this comes into sharper focus. These people fear they are losing their industrious province, and they refuse to stand for it. In this enclave they behave like frontiersmen, wagons drawn in a circle. Shankill people have long represented the most staunch elements of loyalism, the proud British identity which celebrates empire, the royal family, and the Battle of the Somme. If you want to destroy Ulster, it has been said, you start with the Shankill.

For all the talk of the divide, as an outsider walking through the centre of Belfast I cannot begin to tell who is a Protestant and who is a Catholic. But then neither can they. The Shankill Butchers, a gang of loyalist killers who sliced Catholics to death with kitchen knives in the mid-Seventies, searched for clues and even then killed some of their own by mistake. There are no distinct physical characteristics and the accents are more or less indistinguishable – although it is often said that a Catholic will pronounce the letter ‘h’ in isolation as ‘haitch’ and a Protestant will pronounce it ‘aitch’. But in a province where allegiance counts for so much, and where people are quick to categorize one another – rather as my taxi driver could hardly wait until the meter was running to start probing – there are questions commonly asked to uncover allegiance. The answers given to ‘Where do you live?’, ‘Where did you go to school?’ and ‘How many brothers and sisters do you have?’ are good indicators. These are the sort of questions that were once asked at job interviews to gauge an applicant’s suitability. But since these people look the same and talk the same, it amazes an outsider that they need walls to separate them.

The divide is very real, though. It is geographical, economic, political – and of course religious. It is a hoary old question whether the Troubles have been religious in nature, so I felt I ought to ask it as soon as I arrived in Belfast. One man told me that it would be simplistic to blame the Troubles on religion. Nobody has ever been shot dead in the name of transubstantiation. The majority of members of the IRA, INLA (Irish National Liberation Army), UVF and UDA (to account for both sides of the divide) were not religious; they were thinking of their people and their grievances, not God, when engaged in the struggle. On the other hand, without God, Catholicism, and Protestantism there would have been no struggle in the first place. Protestants would not have been sent to settle a Catholic country, there would have been no geographical split, no political discrimination, and no present-day labels to decide who stands on which side of the divide. Catholicism and Protestantism may be little more than symbols nowadays – but the effect of belonging to one or the other religion is much more than symbolic. Only 6 per cent of schools are integrated, the majority of people (more than before the Troubles) live in segregated communities, huge numbers of Catholics know no Protestants, and vice versa. The problem may often be spoken of as cultural rather than religious, but it seems rather simplistic not to allow religion some share of the blame. As Conor Cruise O’Brien almost said, if religion is a red herring, it’s a red herring the size of a whale.

But if it is wrong to speak in terms of a religious conflict, it is surely also wrong to place too much stress on cultural divisions. One Protestant told me sadly about the Catholic man he works with in Derry. ‘He thinks exactly the same way as me,’ he said, ‘there’s just no difference between us. But the pubs in the city are all one or the other, and if I went to one of his pubs, his friends might recognize me.’ A nurse from Belfast agreed: ‘If people had got together, they’d have realized they had so much in common. The Falls and the Shankill houses were much the same, and the people were much the same. When they get away abroad they talk to each other as though they’ve known each other all their lives, and then when they get home they don’t know each other.’ Indeed a 1968 survey found that 81 per cent of northern Catholics and 67 per cent of northern Protestants felt that those of the other community were culturally ‘the same as themselves’. So, while the sides clearly have different political cultures, perhaps it is reasonable to suggest that wherever their political bonds lie, their cultural bonds rest much closer.

Rather than seeing the Ulster divide in religious or cultural terms, it makes more sense to view it in terms of identities that have been created by perceptions of history, by economic and political relations, and by a rejection of the other side’s identity: whatever they are, we are not. Protestants in areas such as the Shankill might have lived lives culturally similar to – and as economically deprived as – their Catholic neighbours, but members of the opposing communities have very rarely worked together towards shared goals. Their tribal identities have not allowed it.

From the Shankill, my taxi driver and I drove across the divide onto the Falls. The atmosphere here is slightly less intense, but the sense of republican identity is as strong as its equivalent on the other side. Just as the Shankill grew up on the old route between the Protestant counties of Down and Antrim, so the Falls grew up on the route out to the Catholic west, and it was populated by workers in the many mills that were built nearby. The Falls saw a great deal of street fighting in the early days of the Troubles, becoming a rallying point for republican resistance to the state. In the words of Provisional IRA hero Brendan Hughes, it was where the belief arose, in 1970, that ‘We can beat these fuckers.’ On that occasion, as so often, the ‘fuckers’ were the British army, who had raided the Falls in an attempt to remove a cache of weapons.

A visit to the Irish Republican History Museum, in Conway Mill, just off the Falls Road, is a memorable experience. At first sight it is a frightening place, full of guns, rubber bullets, prison doors, and clothes worn by the Provisional IRA. It feels like a sinister chapel, Armalite rifles and prison-carved harps in place of crucifixes and stained-glass windows. I have rarely been so self-conscious as I was in my first few minutes in this place; I felt as though I was wearing a Union Jack waistcoat as I wandered about, peering at artefacts and nodding at people who were drinking tea at a small table. I looked around the well-stocked library, then I walked into a recreated cell from Armagh Prison. After a while the place began to seem less like a shrine to violence and more like a focal point for the community. Its custodian is a friendly man, happy to explain the local perspective, and it became clear that the museum’s intention is not to intimidate or to glory in brutality. Just as one side feels at the mercy of its enemies, so can the other, and this place reflects the fear and pride of a beleaguered people. In the end it is an interesting and well-run local museum with little chance of government funding.

When I first visited the Republican Museum, the Real IRA killings at Massereene barracks had not yet occurred. When I returned months later, with a peaceful future looking less certain, the place unnerved me a little once more. It had not changed and its custodian was as thoughtful and generous with his time as he had been on my first visit. But much else had changed, including my attitude to my work. What had begun as a history project, its subject matter more or less packaged, now felt like current affairs muddled with uncertainties. The guns were no longer just museum exhibits. The past and the present were blurring.

Seventy years ago Harold Nicolson wrote, ‘The Irish themselves have no sense of the past; for them, the present began on 17 October 1171, when Henry II landed at Waterford. For them, history is always contemporaneous and current events are always history.’ Walking around parts of Belfast, glancing at the murals and graffiti, it can seem as though the rebels of 1916 have only just risen, and the Somme is still being fought. Sometimes, in ordinary conversation, history comes tumbling out of people. The partition of Ireland or the Siege of Derry can appear as relevant to someone’s state of mind as something that happened that morning. But the versions of the past that you will hear are unlikely to coincide. Identities do not allow it.

There is a Northern Ireland neologism, ‘Whataboutery’, that is used to describe the bouts of accusation-slinging that characterize local politics. When a politician from one side charges the other side with some wrongdoing, the matter will rarely be discussed rationally. Instead it will be answered with a corresponding accusation: ‘What about such and such injustice?’ Whataboutery is symptomatic of the chasm in the interpretation of history that exists between the communities. In Northern Ireland, it has been said, there is no one history. Indeed the Tower Museum in Derry makes the point graphically – it displays the story of the period between 1800 and 1921 along two parallel walls, one from the unionist-loyalist perspective, the other from the nationalist-republican perspective. You can walk down the middle and take your pick. By the same logic, the actions of the dissident republicans ought to be sending the politicians scurrying to their entrenched positions, from where they can interpret events accordingly. But that has not been happening. In the aftermath of the 2009 killings, the politicians have appeared united. The Reverend Ian Paisley, a man often blamed for kindling the fire that led to the Troubles, announced, ‘There is grieving, there is despair, but beyond the despair there is being born a spirit of unity that we have never seen before.’ If he is right – and the very fact that he is saying it suggests that he might be – perhaps this spirit of unity could create a single history in Northern Ireland, a single wall in the Tower Museum. The past might be consigned to the past. If that were to happen, then I would love to revisit the Shankill murals and the Irish Republican History Museum, emotive reminders of a shared turbulent story.

It will take a lot to create just one history, however. The sense and depth of history arises out of continuity, out of a firm linkage of people to place. In parts of Northern Ireland surnames have remained constant for many hundreds of years, and this has created a society where family and community count for a great deal. As one nationalist put it, ‘When we want to get something done here, we phone a cousin.’ In the north, four hundred people can show up to a funeral, and when somebody is shot dead the lives of hundreds can be directly affected. With this continuity comes a sense of history and identity that is rarely questioned.

One Belfast man, whom I met early on in my travels, gave me a warning: ‘All that everyone will say to you here – no matter how much of it seems to be foregrounded on fact – it’s all subjective experience. None of it is true. There is no truth in this place. Anyone who gives you the true version, well, you know immediately not to trust them.’ He had offered me a liar’s paradox: if a Northern Ireland man tells me that in Northern Ireland people don’t tell the truth, how can I believe him? Riddles aside, I was to hear many ‘true versions’ over the coming months, from the senior politician who cheerfully informed me that Catholics cannot be considered Christians, to the ex-IRA man who was certain that the British government retains a strong strategic interest in Northern Ireland. A lot of the time, however, these ‘true versions’ would consist of interpretations that sounded plausible until somebody else said something just as plausible but wholly contradictory. I was to find myself deluged by such declarations of identity. At times I would listen with interest, at other times with weariness – and sometimes with something close to jealousy. Louis MacNeice wrote of his native Northern Ireland:

We envy men of action Who sleep and wake, murder and intrigue Without being doubtful, without being haunted. And I envy the intransigence of my own Countrymen who shoot to kill and never See the victim’s face become their own Or find his motive sabotage their motives.

It is quite possible for an outsider to feel envy in the province, a place seemingly free from doubt. My own world of moral equivalence, where one is not encouraged to pass judgement on the beliefs of others, can seem, by comparison, to be a place without conviction. How fortifying it must be to have something always to believe in, and somebody always to react against. Is this what Dominic Behan wrote about in his lovely song, ‘The Patriot Game’: ‘For the love of one’s country is a terrible thing, it banishes fear with the speed of a flame, and it makes us all part of the Patriot Game’?

Now flip the coin. Perhaps Northern Ireland is a place where judgement is too readily passed. It has produced people prepared to die, prepared to cut off a hand for the cause, but not prepared to make lesser compromises. A weaker identity might produce a stronger society. One Belfast republican told me of time spent, many years previously, in Coventry. There he became friendly with a local Labour Party activist, but he could never understand how someone could be politically active in a ‘twilight city’ where nothing ever happened, where the construction of a zebra crossing was held up as a political achievement. For many in Northern Ireland, politics is not about the mundane or the consensual, it is about the struggle of identities: them and us. Why give a damn about helping kids across a road when there is an identity to preserve?

Alongside intensity of belief can sit self-importance. When a great deal of time is spent gazing inwards, it is possible to lose – or fail to gain – perspective on one’s position in the world. MacNeice again, this time seething with indignation:

I hate your grandiose airs, Your sob stuff, your laugh and your swagger, Your assumption that everyone cares Who is the king of your castle.

In a speech to the House of Commons in 1922, Winston Churchill (a member of the Liberal government team that negotiated the Anglo-Irish treaty with Michael Collins, and, according to his bodyguard, the subject of an attempted assassination by the IRA the previous year) noted that while the First World War might have overturned great empires, and altered ways of thinking across the globe, it had not changed attitudes everywhere: ‘As the deluge subsides and the waters fall short, we see the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerging once again. The integrity of their quarrel is one of the few institutions that has been unaltered in the cataclysm which has swept the world.’ Churchill’s speech has often been quoted to underline the unchanging nature of Northern Irish politics. Yet it is his perception of people so unaffected by world events, so in thrall to their own reflections, that is most striking.

Seventy-nine years later Northern Ireland would gain a perspective of its position in the world. On 11 September 2001, as Al Qaeda mounted a raw and shocking attack on New York City, the Troubles were suddenly made to seem stale, predictable and petty. Blinkers fell away as all parties were forced to look beyond themselves, and to accept that men with stronger senses of identity were now commanding the world’s attention. Fewer people – in particular fewer Americans – now cared who was the king of their castle. September 11 was an attack on all that the world understood, and it shook some of the certainty and self-importance out of Northern Ireland. In its aftermath the move towards peace accelerated.

Not long after I arrived in Belfast, I met a man who told me a story. He had been sitting at home with his wife and small daughter, watching the film Schindler’s List. During a brutal camp scene the man’s wife leant across to him and whispered, ‘Is that what your prison was like?’ The man, a former member of the IRA who had planted bombs, shot at British soldiers, and served time in jail, explained that however hard prison had been for him, however brutal the screws, his treatment could not be compared to that of concentration-camp inmates. The next day, as he drove his daughter to school, the little girl asked him whether he’d really been in prison. ‘Yes.’ ‘But aren’t prisons for bad people?’ ‘Not always. You saw the film last night? Those prisoners weren’t bad people. They were put in prison by bad people. Sometimes the bad people aren’t the prisoners.’

These are the words of a father explaining his past to his daughter, but they could easily be addressed to the world at large. Over the course of this book we will encounter people who have done things that most would consider unacceptable. Some have placed morality to one side more readily than others, but how many of them now consider what they did to be wrong? Some may see their acts as having been politically motivated, in defiance of an unjust system, or in defence of their communities. These may not have been the only – or sometimes even the primary – reasons for their behaviour; they could be handy rationalizations, cynical assaults on a morally sustainable position. But they could also be sincere responses to a complex history, and they may explain why one likeable man feels able to compare his captive status, if not his actual treatment, to that of a Holocaust victim. So how should we approach men who used violence – other than with great care? Is it wrong to judge people in terms of absolutes? While a man may have committed terrible acts in certain situations, in all other areas of life he may have behaved in an entirely moral fashion. If he believes that he had right on his side, can we take him at his own estimation of himself?

We will meet those who suffered the direct consequences of these terrible acts. One man, an ex-police officer – who was himself injured in a bomb attack – told me of arriving at the scene of an explosion to find a friend and colleague lying dead. His reaction had not been one of anger or vengeance, but sadness and a sense of futility. He told me how he would have loved to bring the people responsible down to the scene, where he could ask them exactly what uniting Ireland was about.

We will meet those who never used and sometimes never endorsed violence, but who are entrenched in traditional ways of thinking: people from the Protestant tradition who consider themselves British at a time when Britishness is losing its meaning and relevance for the English, Welsh and Scots; people from Catholic backgrounds whose lives have been devoted to reuniting with the Irish Republic despite its lack of interest in reuniting with them. Slighted by their chosen partners, many of these uneasy neighbours now stand together under the umbrella of the Good Friday Agreement. What divides them unites them.

It is important to remember that the overwhelming majority of people in Northern Ireland, whether Orange or Green, did not participate in, or support, the violence of the Troubles. Yet many of them were affected by it. In 1999 researchers from the University of Ulster published the ‘Cost of the Troubles Study’, for which they had interviewed 3,000 men and women across Northern Ireland to gauge the effects of the Troubles on ordinary people. Of those interviewed, a quarter had seen people killed or injured, a fifth had experienced a deterioration in their health which they attributed to a Troubles-related trauma, and almost one in twenty had been injured in a bomb explosion or a shooting. As well as recording a large increase in alcohol consumption and the taking of medication, the study found a high level of fear of straying from one’s own area and an acute wariness of outsiders.

The ‘Cost of the Troubles Study’ opens up a vista on a world beyond belief and self-importance. It is a world with few spokesmen, but plenty of inhabitants. These are the people whose voices were rarely heard in the reports that filled the English newspapers. One man told me of sitting in a bar on the Falls Road, listening to some old-time republicans boasting of the length of time they’d spent in prison. After a while another man tired of what he was hearing. ‘Fucking lucky for you!’ he shouted. ‘You done twenty years sitting in a safe wee cell? And your family provided for? What about the poor man who had to go out to work every morning, risking fucking death? You were in a fucking sanctuary!’

At the junction between the two worlds, an act of common kindness could attract recrimination. A Catholic man from Claudy told me how he had once tended a policeman who had been shot in the street. He put a tourniquet around the policeman’s leg and sat with him until an ambulance arrived. A while later, at his holiday home across the border in Donegal, an IRA man on the run approached him and asked why he had helped the policeman. He replied that he would have helped a dog if he had needed it. ‘In fact,’ he added, ‘I might even have helped you.’ Days later he was threatened: ‘We’re very worried for you and your family so long as you stay here…’ I asked him how republicans in one town had known of an incident that occurred in another. ‘Kick one of them,’ he said, ‘and they all limp.’

One man who spoke for the citizens of the stifled world was Seamus Heaney. Heaney, a Catholic from Derry, was once asked by Sinn Féin director of publicity Danny Morrison, ‘Why don’t you write something for us?’ ‘No,’ replied Heaney, ‘I write for myself.’ His poem ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’ gives voice to a passive people, too cowed to speak out against ‘bigotry and sham’. According to Heaney, ‘smoke signals are loud-mouthed compared with us’. The poem ends:

Is there a life before death? That’s chalked up In Ballymurphy. Competence with pain, Coherent miseries, a bit and sup, We hug our little destiny again.

A ‘little destiny’ is not much of a thing to hug. It is hardly surprising that so many of the people of Northern Ireland, once denied a life before death, now fear a return to the Troubles; nor is it surprising that tens of thousands of these people gathered in Belfast, Derry, Newry, Lisburn, and Downpatrick to rally for peace in March 2009 in the wake of the dissident killings.

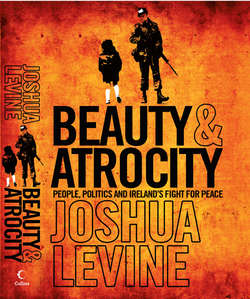

And yet ‘The Grauballe Man’, another of Heaney’s poems from the same collection, includes the words ‘hung in the scales with beauty and atrocity’. Echoing W. B. Yeats, who spoke of ‘a terrible beauty’ born of the 1916 Easter Rising, Heaney is daring to hint at a beauty to the modern Troubles. While giving a voice to those silenced by the violence in one poem, he is suggesting a nobility to that violence in another.

Northern Ireland is built on such contradictions. It was created as a political compromise to bring an end to conflict, but conflict has flourished within it. It goes by the name of ‘Northern Ireland’, but its northernmost point lies to the south of part of the Irish Republic. Its people are divided by religion, but their quarrel is not religious. And while they are divided, they are also united. As a man once said, ‘If you understand Northern Ireland, you don’t understand Northern Ireland.’

As I eased my way into this world of divided, united people, I made my first base just outside the pretty town of Killyleagh, on the banks of Strangford Lough in County Down. I was staying with the Lindsays, a warm and generous family who had never met me before yet welcomed me like an old friend. Katie, their daughter, is a talented artist who works with patients at the Mater Hospital in Belfast. Their lives were a world away from my own in London, but I quickly became very adept at lighting a wood fire, and sitting by it with a glass of whisky. Through the Lindsays I had the fortune to meet Bobbie Hanvey, a photographer, writer, broadcaster, and one-time nurse in Downshire mental hospital, a man described by J. P. Donleavy as ‘Ireland’s most super sane man’.

Bobbie hosts a programme, The Ramblin’ Man, every Sunday night on Downtown Radio, in which he interviews local personalities. His easy-going charm allows him to get away with asking some very awkward questions. He prised several seconds of rare silence from Ian Paisley by asking him whether, had he been born a Catholic, he could have been a member of the IRA. It cannot be easy for Paisley to accept that God could have made him a Catholic, never mind that he could have been a member of the IRA. The eventual answer was, ‘No, I don’t think so,’ followed by an unprovoked denial that he had ever supported loyalist violence. A Hanvey trademark is the undercutting of a serious subject with a flash of mischief. He interrupted the ex-leader of the UVF, in mid flow on the subject of large booby traps, with the observation that the biggest booby trap he’d encountered was a brassiere. He also advised a Chief Constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), who had once worked in vice, to write a memoir with the title Pros ’n’ Cons. Nonplussed, his guest thanked him for ‘that very impressive suggestion’.

But Bobbie’s irreverence cannot mask a keen intellect and a shrewd understanding of the complexities of Northern Ireland, from which he seems to stand aloof, friendly with men and women of all sides. I would become very grateful for his insights, and even more grateful for the chance to quote from his interviews in this book. One of my abiding memories of my time in Northern Ireland is of an evening spent upstairs in his Down-patrick house, listening to recordings of interviews. As I wondered where I could get something to eat, I heard footsteps coming up the stairs and Bobbie appeared in the doorway, his Marty Feldman hair silhouetted against the light. He walked in and plonked a plate down in front of me, on which sat two foil-wrapped chocolate marshmallows. ‘I’ve got to tell you,’ he said, ‘I’m not much of a cook.’

Maybe not, but he was a very helpful ally in this strange and familiar place. He phoned me recently, asking me to find him a couple of Chasidic Jews to photograph. As though I’d have them around the house. That’s fair enough, though. He’s brought me his people. He can have a pair of mine.