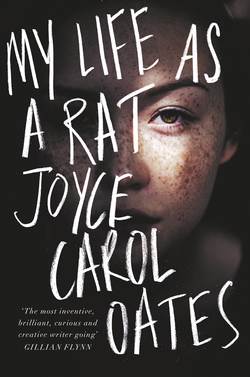

Читать книгу My Life as a Rat - Joyce Carol Oates - Страница 22

The Secret I

ОглавлениеTHERE IS A SECRET BETWEEN MY MOTHER AND ME. ALL THESE years in exile, I have told no one.

In fact, there are secrets. Which one shall I reveal first?

In sixth grade I’d become friendly with a girl named Geraldine Pyne. Several times she invited me to her house after school, on Highgate Avenue. Her father was a doctor in a specialty that made me shiver—gastroenterology. She lived in a large white brick house with a portico and columns like a temple. When I first saw Geraldine’s house I felt a twinge of dread for I understood that my mother would not like me to visit there and would be unhappy if she knew.

I understood too that my father would disapprove, for my father spoke resentfully of “money people.” But my father would not ever know about Geraldine Pyne, and it was possible that my mother would.

On days when Geraldine invited me to her house for dinner Mrs. Pyne usually picked us up after school, and either Mrs. Pyne or her housekeeper drove me home afterward; there was no suggestion that my mother might come to pick me up.

Mrs. Pyne’s station wagon was not a very special vehicle, like the long, shiny black Lincoln Dr. Pyne drove. So if my mother happened to glance out the window, and saw me getting out of it, she would not have been unduly alarmed or suspicious.

And Geraldine too, if Mom happened to see her, did not look like a special girl. You would not have guessed from her unassuming appearance (pink plastic glasses, glittering braces, shy smile) that she was the daughter of well-to-do parents, or even that she was a popular girl (with other girls and with our teacher, at least) and an honors student.

Geraldine was an only child. This seemed magical to me. As my sisters and brothers, all older than me, seemed magical to her.

“You would never have to be alone,” Geraldine said wistfully.

I tried not to laugh. For this was not true, and why would anyone want it to be true? An only child could have no idea of the commotion of the Kerrigan household.

It was embarrassing to me that Geraldine should confide in me that her parents had hoped for another child, but God had not sent one. In the Kerrigan family no one spoke of such intimate matters casually. I could not imagine my mother or father sharing such information with me.

I was grateful not to be an only child. My parents would have only me, and I would have only them, to love; it would be like squinting into a blinding light that never went out.

I did not feel comfortable inviting Geraldine to our house for I believed she would be embarrassed for me. Especially, she would see my mother’s weedy flower beds, that were always being overwhelmed by thistles and brambles, and coarse wildflowers like goldenrod, so different from the beautiful elegant roses in her mother’s gardens, with their particular names Geraldine once proudly enunciated for me, like poetry—Damask, Sunsprite, Rosa Peace, American Beauty, Ayrshire. Geraldine would see how ordinary our house was, though my father took great pride in it, a foolish pride it seemed to me, compared to the Pynes’ house: as if it mattered that a wood frame house on Black Rock Street was neatly painted, and its roof properly shingled, drainpipes and gutters cleared of leaves, front walk and asphalt driveway in decent condition though beginning (you could see, if you looked closely) to crack into a thousand pieces like a crude jigsaw puzzle. Especially Geraldine would wince to hear my older brothers’ heavy footsteps on the stairs like hooves and their loud careening voices like nothing in her experience, in the house on Highgate Avenue. And there was the possibility of my elderly grandfather emerging from his hovel of a room at the rear of the house, disheveled, unsteady on his feet and bemused at the sight of a strange young girl in the house —Hey there! Who’in hell are you?

But then, my mother discovered that my friend Geraldine’s father was a doctor—Dr. Morris Pyne. She was shocked, intrigued. She insisted that I show her where the Pynes lived and drove me to Highgate Avenue to point out the house to her. This was a request so utterly unlike my mother, who rarely left the house except to go shopping and to church, and who rarely evinced any interest in her children’s school friends, I’d thought at first that she could not be serious.

“Oh, Mom. Why d’you want to know? It’s not that special.”

“Isn’t it! Highgate Avenue. We’ll see.”

No one would know about this drive. Just Lula and Violet Rue, seeking out the residence of Dr. Morris Pyne and his family at 11 Highgate Avenue.

It was as I’d dreaded, the sight of the large spotlessly-white brick house with portico and columns, in a large wooded lot, was offensive to my mother. “So big! Why’d anyone need such a big house! Show-offy like the White House.” Mom’s voice was hurt, embittered, sneering.

Beside her I shrank in the passenger’s seat. In horror that, unlikely as it was, Mrs. Pyne might drive up beside us to turn into the blacktop driveway, that looped elegantly in front of the house, and recognize one of her daughter’s school friends in the passenger seat of our car.

I tried to explain to my mother that Geraldine Pyne was one of the nicest girls in sixth grade. She was not a spoiled girl, and you would never guess that she was a “rich” girl. A very thoughtful girl, a quiet girl, who seemed for some reason (God knows why) to like me.

“She thinks I’m funny. She laughs at things I say, that other people don’t even get. And Mrs. Pyne is—”

Rudely my mother interrupted: “They look down their noses at us. People like that. Don’t tell me.”

I had never seen my mother’s face so creased, contorted. At first I thought she must be joking …

“Oh, Mom. They’re nothing like that. You’re wrong.”

“And what do you know? ‘You’re wrong’—like hell I am.”

Driving on, furious. I could not think of a thing to say—my mother whose chatter was usually affable and inconsequential, like a kind of background radio noise, was frightening me.

As we drove in a jerky, circuitous route back home my mother recounted for me in a harsh, hard voice how as a girl she’d cleaned “the God-damned” houses in this neighborhood. Rich people’s houses. She’d had to quit school at sixteen, her family had needed the income. At first she’d cleaned houses with a cousin, who did the negotiating, then it turned out the cousin was cheating her, so she’d worked on her own. Five years. She’d worked six days a week for five years until she met my father and got married and started having babies and taking care of a house of her own, seven days a week. Her voice rose and fell in an angry singsong—

quit school, sixteen, got married, started having babies. Seven days a week.

There was a particular sort of bitterness here directed at me. For I was one of the babies. And I’d betrayed her with my careless, insulting friendship among the enemy.

“In those houses I had to get down on my knees and scrub. Kitchen floors, bathroom floors. I had to clean their filthy tubs and toilets with Dutch cleanser. Toilet brushes, Brillo pads. I had to strip their smelly beds and wash the sheets, towels, underwear and socks. I had to drag their trash containers out to the curb, that were so heavy my arms ached. Sometimes the kids would come home from school before I was finished, and they’d get their bathrooms dirty again, and I would have to clean them again. Sinks I had scrubbed clean, mirrors I had polished, I would have to do again. Piss splattered on the floor. They laughed at me—the boys. God-damned brats. If they even saw me at all.”

Distracted by these memories my mother was driving erratically. Her eyes brimmed with tears of hurt. None of us—her children—had ever known of this hurt, I was sure—I was sure she’d never told anyone, for by now I would have known.

“Oh, they thought they were so generous! Sometimes they gave me food to take home, leftovers in the refrigerator they didn’t want, spoiled things, rancid things, garbage—‘Here, take this home please try to remember to return the Tupperware bowl next week.’ I wasn’t supposed to spend more than twenty minutes on lunch. I wasn’t supposed to sit down—they never like to see a cleaning-woman sitting down, that’s offensive to them. Or using one of their God-damned bathrooms. If you have to wash your hands, use a paper towel. Not one of their God-damned towels. Some of the big houses, I’d work all morning, so hungry my head ached. That house! I worked in that house—I remember …”

I tried to protest: the Pynes had not been living in the white brick house so long ago. They had only moved in a few years ago. It had to be other people she was thinking of. Mrs. Pyne was a polite, kind, wonderful woman, not a snob, not cruel—

Bitterly my mother interrupted: “You! Stupid child! What do you know? You know nothing.”

I had never heard my mother speak in such a way. It was as if another woman were in her place, savage and inconsolable.

We were slowing now in front of another, even grander house, at 38 Highgate—a Victorian mansion behind a six-foot wrought iron fence with a warning sign at the gate—PRIVATE. DELIVERIES TO THE REAR.

“And this house—I’ve been in this house, too. And your father has not.”

Not sure what this meant I said nothing.

“D’you know who lives here?”

Yes, I did. I thought that I did. But I played dumb, I said no. I did not want to incur any more of my mother’s wrath.

“Your father never knew. I never told him. That I was a house maid on Highgate Avenue. That my parents forced me to work. Forced me to quit school. And one of the houses I cleaned was ‘Tommy’ Kerrigan’s—this house. Maybe ‘Tommy’ doesn’t live here any longer—maybe he’s retired and living in Florida. Maybe he’s dead—the bastard! When he was mayor of South Niagara, and married to a woman named Eileen—his second wife, or his third. She was the one who hired me and paid me but ‘Tommy’ was on the scene sometimes in the morning when I came to work. Just getting out of the bathroom, getting dressed—filthy pig. Once, he dared to ask me if I would clip his toenails! Saw the look in my face and laughed. ‘It’s all right, Lula, my feet are clean. Come look.’ Mrs. Kerrigan never knew how her husband behaved with the help—the female help. If she knew, she pretended she didn’t. All of those rich men’s wives learn how to pretend. Or they’re out on their asses like the female help. She paid me below the minimum wage. She paid me in dollar bills. I had to polish the God-damned silver—the Kerrigans were always having dinner parties. Had to breathe in stinking pink silver polish that made me sick to my stomach. Terrible bleach I had to use, that almost made me faint. And ‘Tommy’s’ side of the bed—shit stains. I’d hoped to God he had not done it on purpose. But I was grateful for work, I was just too young to know better. The black maids would work for less money than we could so after a while, there weren’t any white girls working on Highgate. I doubt there’s any ‘white help’ in South Niagara today. Your father never knew any of this. He lived in his own cloud of—whatever it was—wanting to believe what he wanted to believe. Most men are like that. Jerome doesn’t know to this day that I ever set eyes on Tommy Kerrigan up close. He doesn’t know that I was on my knees in this God-damned house, or in any of these houses. He’d seemed to think that I had no life before I met him—he never asked about it. He’d never have wanted to touch me—if he knew …”

We were out of the neighborhood now. My mother was driving less erratically. Her fury was abating, her voice quavered with something like shame. I could think of nothing to say, my brain had gone blank and it would be difficult for me to remember afterward what my mother had said, and why she had said it; what humiliating truths she’d uttered as I sat stiff beside her in the passenger’s seat of the car not daring to look at her.

It was the most intense time between my mother and me. Yet, I would remember imperfectly.