Читать книгу Fragments of War - Joyce Hibbert - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Athenia Survivor

I’m not afraid of submarines or anything like that and I’ll come back when I’m well.”

Thirty-four-year-old Barbara Bailey was trying to reassure her parents as she bade them a tearful farewell in London, England. The date was 31 August 1939.

As her private world had been shattered in the preceding weeks, she knew she had to get away. Now she was off to Canada where she would help care for her brother’s baby girl in Calgary.

By this move she would avoid a complete breakdown while trying to forget the man who had been the cause of her anguish: Reg, who had ended their fourteen-year-long ’understanding’ when he had announced his engagement to a young girl. As though to purge him from her life Barbara wrote him that final letter.

The Adelphi Hotel,

Liverpool, England

1 September 1939

... And this Reg, is probably my last night in England – not for good – I am coming back when I am fit again. Tomorrow, who knows – we shall probably be at war but for the first time in many months I am calm, nothing is real.

... And now to forget – forget every second of happiness I had with you and to forget how many times and how deeply I have paid for it....

Because of her highly nervous state in the weeks before her departure, there had been frequent tears and turmoil at home. From the Adelphi Hotel on that first of September she also wrote a letter to her mother.

... Several hotels seem to be closed down so was almost compelled to come here. It’s dearer than I wanted but overwhelming attention.

... I feel much better already and am now off to enquire about the Athenia. Someone behind me is saying “I haven’t said goodbye to my mother or anything – I’ve never done that before.” That’s just how I feel, terribly casual about leaving now.

I ought to have brought my gas mask with me, everyone has a brown square parcel I see.

I’ll write again before sailing if possible....

The 15,000 ton Donaldson Atlantic Line steamship had embarked passengers at Glasgow and Belfast. With this final group boarding at Liverpool her passengers and crew would total 1400 persons. The Athenia was bound for Montreal carrying British, Canadian, and American citizens, as well as about sixty European emigrants and refugees fleeing Nazi oppression.

Barbara Bailey’s valuables went down with the ship’s safe.

As she boarded the already blacked-out liner, Barbara Bailey had the immediate and disquieting impression that the Athenia was over-crowded. (According to 4 September 1939 edition of the The Evening News, the Athenia had the largest number of passengers on board for many years.) She was annoyed at having to share a cabin with the three other women already in it. Some husbands and wives had been separated for the voyage in order to permit four women or four men to a cabin.

Late in the afternoon of Saturday, 2 September the ship sailed out of Liverpool.

Next morning, free of seasickness, Barbara Bailey attended shipboard church service and afterwards joined the soberfaced passengers clustered around a notice board. In shocked silence they were reading a bulletin announcing Britain’s declaration of war against Germany.

As if sleepwalking, she continued on her way to the dining room where the atmosphere was heavy with gloom. Her personal control broke and she burst into tears. One of the stewards urged her to pull herself together and quietly encouraged her to begin her lunch. To help, he even fed her a few spoonfuls of soup. War, she was wondering, what would it mean? An exchange on deck that afternoon had topical significance. “We will bomb Croydon” a German woman boasted, to which Barbara started to retort “When we bomb Berlin ...” Whereupon the woman had interrupted “I don’t think we’ve considered that.” The Englishwoman had the last word. “If you can get to Croydon, we can get to Berlin!”.

Thus the ship buzzed with talk of war and Barbara Bailey sensed that people were greatly relieved to be on their way to North America, and away from it all. Indeed, she felt that she might be the only passenger feeling guilty and distressed about leaving Britain behind at such a perilous time.

While the First Sitting group were at dinner that evening Barbara lined up for a previously reserved bath. But the Second Sitting gong sounded and she had to miss it. Hurriedly she put on her bright reddish-mauve dinner dress, brown leather shoes with slatted fronts, and grabbed the matching handbag. She sat at a table with four other women. The sixth place was reserved for the Chief Radio Officer. His seat would remain empty. She began eating her cold salmon....

Next day, 4 September, Mr. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, rose in the British House of Commons to make a statement. He began:

“I regret to inform the House that a signal was received at the Admiralty about 11 p.m. last night giving the information that S.S. Athenia had been torpedoed in a position about 200 miles north-west of Ireland at 8:59 p.m”

The news of the swift and brutal attack on an unarmed passenger liner was to reverberate around the world. Three quarters of her passengers were women and children, 311 passengers were neutral Americans, and 112 lives were lost.

“I remember a tremendous shattering bang ... lights going out ... the ship lurching ... shouts ... excitement!” Barbara Bailey would relate.

It was at that precise time – the moment of explosion – that she felt her common sense and recent Civil Defence training taking over, “AVOID PANIC AT ALL COSTS”, that was rule Number One.

As diners began to rush, pushing and screaming toward the main stairs, she urged the two women nearest her at the table to keep their heads. “Let’s wait, we may be doomed but don’t let’s get crushed to death,” she begged.

Through the din they could hear the loud authoritative voice of a ship’s officer, “KEEP CALM”, he kept repeating over and over again. He peered into the dimness of the large debris-strewn dining room.

“Is anyone still in here?”. Barbara Bailey explained that they’d waited for the end of the rush.

“Leave now,” he ordered. Obediently the three women made their way up the stairs through the remains of tables, chairs, crockery and potted plants which had been swept along and upwards by the frantic passengers.

Suddenly Barbara thought that she ought to be wearing her life-preserver and coat. She turned and went back below groping about in the darkness while unsuccessfully trying to locate her own cabin. Fighting the choking fumes in the passageways and stumbling over cabin trunks, she eventually found a lifejacket and warm coat. Then as quickly as possible she went back up on deck.

“Passengers were running about, calling out names of loved ones. Some people had been blown into the sea when the torpedo hit. I looked down into the water and saw a woman’s body floating by, clothes ballooned out. My mind reluctantly registered ‘dead’.

“I noticed that many passengers had no warm clothing and started out to go below to see whether I could find some blankets but my way was firmly barred by a determined stewardess. By this time I realized that I was perfectly self-possessed and acting as though it were an everyday event for me to be shipwrecked.”

She recognized the kindly steward from the dining room. He was hunched over and shaking. Their roles reversed, she grasped his shoulders telling him to control himself and give some help where he could.

Snatches of talk reached her, “... yes, they’d been hit by a torpedo,... one man had seen a submarine’s conning tower.”

Wandering about the ship, she saw that several lifeboats on one side of the Athenia were damaged. Ship’s crew, with help from passengers, were manning stations; one lifeboat had already been successfully lowered into the water. Saying a silent prayer as she watched some passengers tipped out of another on its erratic downward journey, she could only hope that the poor devils would be picked up.

Still wandering, she began consciously searching for a less crowded lifeboat station. Up on the boat deck she was hailed by a man in charge of a station and he insisted that she get into Lifeboat 8A.

“I looked over the side of the listing Athenia and far below there was a bobbing lifeboat seemingly full of people. I decided to obey the man’s order anyway. I laid my handbag down and asked one of the men to tear my skirt so that if necessary, I could jump more easily. He ripped the skirt up one side and helped me attach my handbag to my belt. Then wishing me luck and instructing me to hang on to the steel cable leading to the lifeboat, he sent me over the side. Down and down I went, hand over hand with feet sliding on and off the cable until finally they came to rest on a ledge. Someone pulled at the hawser sharply – I felt more movement – and imagined that the lifeboat below was moving away. Was this the end for me? Should I drop into the water and take my chances? Just then a voice yelled ‘Come on, you’re doing fine.’ My ankles were gripped and I was literally thrown into the lifeboat on top of others. We pulled away immediately. We were seventy living and one dead.”

In sole charge of 8A, a navy blue-jerseyed seaman gave instructions, kept order, and worked unceasingly. Barbara Bailey was to remember him by the name Eileen embroidered on his seaman’s jersey but never learned his real name.

The passengers were packed like sardines and suffering the miseries of seasickness. They had no choice but to vomit on themselves and each other. Sea water washed around their ankles, and knees met those of the person opposite. A little girl near Barbara began to scream. Again the advice “AVOID PANIC” flashed through her mind and Barbara Bailey clapped a hand over the child’s mouth.

Seaman Eileen was careful to steer his boat away from the bright silvery path cast by the moon.

The one undamaged motorboat from the Athenia approached. A male voice announced that two more passengers needed space in the lifeboat. Eileen objected, shouting that they were overcrowded already. “They’re coming anyway” was the reply and before she had time to brace herself a man’s body landed on Barbara Bailey’s back. Then others placed their arms across her back to break the force of the second man’s arrival. The men brought news that a radio message had been received on the Athenia that rescue was on the way. One of the newcomers had a bottle of whisky. Barbara Bailey asked for a drink but the whiskey was not for sharing.

In that long uncomfortable and frightening night, Lifeboat 8A was being rowed steadily further and further away from the Athenia’s listing hulk. Help was indeed on the way; a Norwegian merchantman was steaming towards them.

“Its twinkling lights reminded me of a fairy castle. I’ll never forget the sight of the Knute Nelson as she came full speed to our rescue.”

Yet at first sighting Barbara Bailey had had misgivings about the vessel and speculated out loud that it might be the German liner Bremen. The idea alone was enough to terrify the refugees. The men downed oars and the Jewish women set up an eerie wailing. Still doubtful about the ship’s nationality she suggested to one frightened man that in order to conceal his identity, he should throw his passport overboard, which he did.

Fears were replaced by relief as the freighter’s crew quickly implemented rescue operations. Barbara Bailey watched as women and children were hoisted aloft in a bosun’s chair while men climbed up a swinging rope ladder. By the time it was her turn, a gangway had been lowered and it ended six to eight feet above her head. She stepped carefully over the body of a dead woman and was unceremoniously thrown by three men up into the arms of a huge young Norwegian sailor standing on the gangway.

Her ordeal in the lifeboat had lasted seven hours. “I had to climb over the side of the Knute Nelson where I was met by another big sailor who immediately took a knife to my lifejacket. One slash and it was off.

“In a small galley, where cockroaches abounded, I was issued a drink of gin. I took it outside and gave it to a terribly burned, half-naked man. Working below decks, he’d been badly scalded and salt water had got into the wounds. The poor man was obviously close to death.

It was late and I was exhausted. I looked for somewhere to sleep. The captain’s and officer’s quarters were packed with survivors. I saw a Polish woman toss aside the captain’s clothes and hang her husband’s long overcoat in their place. Damned cheek, I thought. About an hour after our rescue I bedded down on deck with a life-preserver as my pillow. I was hungry, cold, and tired. But oh! the joy of being alive!

“Toward dawn I heard a sailor shouting ‘Hot drink. Hot drink.” I followed him to a larger galley where he gave me a mug of something that tasted like coffee mixed with beef extract. The crew of the Knute Nelson were so kind giving us their beds, food, clothing, and willing attention., Food for the day was one egg, one potato in its jacket, one piece of hard tack biscuit, and tea. For these rations a little Cockney steward from the Athenia lined us up and kept a sharp eye out for anyone trying to get extras. The Poles in those distinctive long overcoats (under which they’d tried to smuggle possessions into lifeboats) got particular attention.”

Walking into a room full of injured, Barbara Bailey found the sight and smell overpowering. In addition to the wounded, there were several women who had started heavy periods.

An injured man called her over. She noticed that his hands were badly burned and lacerated. Asking her to take his wallet from his pocket and look after it for him, he explained that he was an embassy clerk and his papers must be destroyed if the enemy should appear. Steel hawsers had burned and torn his hand when he helped lower a lifeboat full of people. Nevertheless, the courageous Scot had rowed in one of the lifeboats.

Daylight came and in the distance they could see the doomed Athenia. On 5 September the Knute Nelson and her gallant crew reached Galway, Ireland carrying 430 Athenia survivors. Red Cross workers hurried aboard and removed the injured. Barbara Bailey had sustained a leg burn when she slid down the steel cable into the lifeboat. She accompanied the embassy clerk to hospital.

“I watched as they went to work on those damaged hands of his and then all of us – doctors and nurses included – drank a generous slug of whisky.”

Before crossing to Glasgow, the survivors stayed two nights in Galway. During the first night Barbara Bailey, not surprisingly, had “a nightmare or something” which really frightened the other two women in the room.

8 September 1939

My dear Barbara,

We all had a very anxious time. Lottie telephoned at 8 o’clock on Monday morning and enquired whether you were with us. When I told her that you had left Liverpool on Saturday she said “Good God, the boat has been torpedoed.”

... On Tuesday when we heard of those that had reached Glasgow and that you were not with them we rather lost heart. However your telegram reassured us.

We should dearly like to have you home but we feel that you alone should decide as to this. Life will be very dreary here particularly when it is dark and the perpetual dread of an air raid. Air raid warning on Tuesday morning for about two hours. If you go to Canada we shall feel that you and Fred are safe.

... Should you go to Canada your mother and I hope that we shall be spared to see you as soon as the War, which must be a terrible one, is over.

With fondest love,

Your affectionate father

Fred W. Bailey

Barbara Bailey, fit and determined, returned to live at Bookham Common near London for the duration of the Second World War. She firewatched, drove an ambulance and did office work for her solicitor father. The family home in East Dulwich was bombed three times and her parents were forced to move to their weekend bungalow at Bookham Common. The bungalow sustained bomb damage on two occasions.

Bookham Common was used extensively by the military and bombed frequently. It was on the Common that she met the Canadian soldier who became her husband.

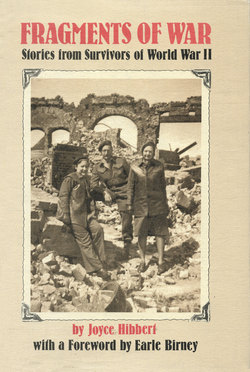

The late Laura Bacon and her son Keith posed on the deck of the Southern Cross, a New York bound ship that rescued them after the sinking of the Athenia. Laura Bacon, the aunt of Stanley Salt of Chapter Three, is wearing replacement clothes given her for her wet torn ones, while the package under her arm is all that remained of her luggage.

Six and a half years after the Athenia sinking she sailed for Canada again; this time the ship was the grand old Cunarder, the Aquitania. Peacetime luxury liner turned troopship, she was converted again, into a war bride transport. Barbara Bailey was one of many hundreds of war brides on board bound for Halifax and points beyond.

Meanwhile, the Germans denied responsibility for the Athenia sinking. They claimed that she had been sunk by three British destroyers.

In January 1946 at the Nuremberg trials, the truth was revealed. During the case against Admiral Raeder a statement by Admiral Doenitz was read. In it he admitted that the Athenia was torpedoed by U-30 and that every effort was made to cover the fact. Those efforts began early with steps taken by the U-30 commander, Captain Lemp.

The commander contended that he had mistakenly identified the Athenia as an armed merchant cruiser. When he realized his error, Captain Lemp, later killed in action, hid his error by omitting to make an entry in his log book and by swearing his crew to secrecy.

An affidavit from Adolph Schmidt, a surviving member of the U-30 crew, was produced as evidence. He told of how, later in September when he had been severely wounded and due to disembark, Captain Lemp had presented him with a document insisting that he sign it. The wording was

I, the undersigned, swear that I shall shroud in secrecy all happenings of 3 September 1939, on board U-30, regardless of whether foe or friend, and that I shall erase from memory all happenings of this day.

Was she haunted by the Athenia experience?

“Not until it came time for the first lifeboat drill. The war was over but I was appalled that many women kept on chattering and did not listen to instructions. Some didn’t even bother attending. I discussed it with a war bride who’d been a survivor of a ship sunk in the Mediterranean. We both knew the importance of those drills.” And both women were happy to sail to Canada and peace for their new married lives.

Barbara Bailey Durant, Athenia survivor, settled on a small farm in the Ottawa region and worked alongside her husband.