Читать книгу Standing Our Ground - Joyce M. Barry - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

I became aware of the process of mountaintop removal coal mining (MTR) in late 1997 during a visit home to West Virginia. While visiting family, I read local newspaper reports on this controversial form of coal extraction. Many people were becoming more cognizant of changes in the coal industry that ushered in this highly mechanized form of coal mining, and some were horrified by its damage to the lush Appalachian Mountains, and the displacement of small communities in the coalfields. Other citizens defended the coal industry and its place in the state’s history and economy. Indeed, mountaintop removal coal mining has been controversial since its beginnings, and continues to polarize citizens in the “Mountain State.” When I returned to Ohio after my trip home, the New York Times, Washington Post, and other national publications were beginning to report this emerging story from the coalfields of central Appalachia.

In early 1998 I visited Larry Gibson’s camp on Kayford Mountain in West Virginia and saw an MTR site for the first time. Like many people who view the massive environmental alteration known as mountaintop removal, I was shockingly disturbed that MTR was legal and occurring in my home state. Four generations of my family have lived in the coalfields of West Virginia. My father worked as a coal miner, and my mother was a stay-at-home mom who raised six children in Eccles, West Virginia. Growing up in the Appalachian Mountains, I have a deep affinity for this landscape, as do many people from this region of the United States. Coming of age in West Virginia, the beautiful mountains that surrounded us were inextricably linked to our history, culture, and sense of place in the world. To learn they are now razed for coal extraction, left in ruins by heavy machinery and the technicians who operate them, is simply unacceptable, and far too much to bear for many Appalachians.

When I first began researching this topic, I quickly learned that many West Virginia women and their families were being impacted by MTR operations, and were forming or joining organizations designed to raise awareness about MTR and galvanize support in the fight to end it. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, coalfield women such as Freda Williams, Janice Nease, Pauline Canterbury, Mary Miller, Judy Bonds, and others began to speak out against MTR and its effects on humans and the natural environment of coalfield communities. These early participants helped put the issue on the political and environmental map. Women began monitoring MTR sites, attending state permit hearings, lobbying the state and federal legislatures, and engaging media to educate the public on coal-related issues. For example, many of these women frequently wrote letters to the editor in state newspapers; organized and participated in road shows such as Appalachian Treasures; and spoke at colleges, universities, and community groups throughout the country. Some women worked with scientists and members of the state EPA to collect air quality samples that demonstrated Big Coal’s impact on the quality of life in mountain communities. In short, women grassroots activists in this movement have taken a multipronged approach in their fight against MTR and Big Coal in Appalachia. Their presence in this movement has been vigorous and consistent, and women, in large numbers, still serve these vital roles today as the movement changes and progresses.

Central Appalachian Coal-Producing Region

I have spent more than a decade researching mountaintop removal through an environmental justice lens and conducting fieldwork in central Appalachia, primarily in the coalfields of southern West Virginia. Over the years I have toured MTR sites, visited vanishing coal towns, met with ex–coal miners and families whose homes are at ground zero for MTR operations, drank coffee with professional environmentalists, talked with lawyers and policymakers, and of course met many grassroots activists working to end MTR and mitigate the deleterious effects of Big Coal in Appalachian mountain communities. Until the middle part of the 2000s, this topic was very difficult to write about. Academic resources were limited, and I frequently had to rely on journalistic accounts to support the research I was gathering on the ground in West Virginia.

Despite those early reports in the 1990s, and Ken Ward Jr.’s groundbreaking series “Mining the Mountains” in the Charleston Gazette, the issue of MTR was slow to grab national mainstream attention. National environmental groups had little to say about mountaintop removal, and academic analyses were rare. I published the first scholarly article on this topic, “Mountaineers Are Always Free: An Examination of the Effects of Mountaintop Removal in West Virginia,” in Women’s Studies Quarterly in 2001. At the time of this writing, there is only one other academic book on this subject: Shirley Stewart Burns’s Bringing Down the Mountains, but additional academic treatment of this multifaceted topic is certainly warranted. I am happy to report that thanks to the sustained and vigorous grassroots activism in Appalachia, mountaintop removal coal mining is now a national and international issue. Mainstream environmental groups have taken notice, and additional academic work is being published on what many consider one of the greatest human and environmental tragedies of our time.

This book situates MTR and the environmental justice (EJ) activism against it within a particular time period, 1998 to 2012. Surface mining has existed, in some form or fashion, for decades in Appalachia.1 However, MTR operations increased in the 1990s, the mainstream press began covering this story in that decade, and organized environmental responses to mountaintop removal became more vigorous and focused during this decade.2 For example, one of the most prominent West Virginia groups, the Coal River Mountain Watch (CRMW), began in 1998 as a direct response to the incursions of MTR on small communities in Boone County, West Virginia.3 The Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (OVEC), based in Huntington, West Virginia, was formed in 1987 and has focused much of its energy on MTR and other coal industry abuses since the late 1990s.4 Regional organizations such as Appalachian Voices, based in Boone, North Carolina, began offering financial support to the budding anti-MTR movement in the latter part of this decade as well.

I should also make clear that the anti-MTR movement does not focus exclusively on MTR, but serves as a general watchdog for Big Coal, monitoring its assaults on both the human and the nonhuman environments. For example, activists raise awareness about many industry practices deemed harmful as well as the impact of coal on human health, publicize information on coal containment issues, and counter the coal lobby in Washington. Judy Bonds frequently referred to mountaintop removal coal mining as a “poster child” for the detrimental effects of coal production and consumption and the need for the development of alternative energy sources.5 Sadly, Bonds, codirector of the CRMW, died of cancer in January 2011. This book is dedicated to her memory.

In addition, this manuscript refers to the coal industry as Big Coal, rather than King Coal, because the former denotes one of the most powerful global industries, while King Coal suggests a company operating solely in the Appalachian region as in the older days of coal. In short, Big Coal is more encompassing and reflective of the current political-economic hegemony in relation to the production and consumption of coal. As Coal River Mountain Watch member Sarah Haltom says, the greatest challenge to those fighting MTR is that “we at the grassroots level are dealing with one of the biggest industries in the world that has so much money and power.”6 Despite the enormity of Big Coal’s influence, activists continue to work for environmental justice and sustainable coalfield communities.

Mountaintop Removal Coal Mining and Big Coal in West Virginia

Let’s consider the well-established facts of this coal extraction process bluntly designated “mountaintop removal.” This mechanized form of surface coal mining has existed for decades but became more prevalent in the 1990s because of an increased demand for electricity. MTR removes central Appalachian mountains away from coal seams through large-scale blasting and the use of heavy machinery that scoops up the coal, moving the waste into nearby containment sites called “valley fills.”7 Mountaintop removal differs from previous incarnations of surface mining, not only in that it concentrates on removing mountaintops, but also, and most notably, by the sheer scale of these operations. “The greatest earth-moving activity in the United States” is an apt description, considering the data assessing the scope of MTR: An average MTR site removes 600–800 feet of mountain, stripping roughly 10 miles, dumping the waste from this process into 12 valley fills that can be as large as 1,000 feet wide and a mile long.8 Figures from 2009 estimate that in Appalachia, 6,000 valley fills impacting 75,000 acres of streams have been approved.9 “Earth-moving,” indeed.

According to scientists, MTR is causing irreparable damage to the central Appalachian landscape. On average, twenty-five hundred tons of explosives are used by technicians daily in Appalachian communities to blast the mountaintops, covering nearby streams with waste, throwing ecosystems out of balance, and causing increased flooding and the loss of biodiversity in the mountains.10 Area water supplies are contaminated by the use of valley fills, and also by the containment of toxic wastes from processing coal into nearby earthen dams called slurry ponds.11 The impacts on human health are considerable. Scientists note an increase in respiratory and heart problems by citizens living in mining zones, including chronic pulmonary disorders and lung cancer.12 Mortality rates are also elevated in areas surrounding surface mining locations.13 A most recent scientific study indicates that higher birth defect rates occur in mountaintop removal mining areas in Appalachia.14

West Virgina Coal Counties

Mountaintop removal coal mining was made possible by federal attempts to regulate strip-mining in the United States through the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA).15 The legislation permitted surface-mining as long as coal companies were able to reclaim and return mined areas to their “approximate original contour” (AOC) to repurpose the affected land into sites for commercial or residential use.16 However, a variance to the AOC rule was permissible if mountaintops were being removed. Because MTR mines cannot return mountains to their approximate original contour, coal companies receive an AOC variance as long as they demonstrate that the mined land will be used in a way “equal to or better than the way it was used” before mining operations began.17 The realities of reclaiming the land postmining are predictable: coal companies spend less than 1 percent of revenue on land reclamation, spraying hydroseed and coating rocks with a mix of “fertilizer, cellulose mulch, and seeds of nonnative grasses,” before moving on to the next operation.18 Economic development takes place on less than 5 percent of flattened areas that were once mountains.19 In addition to SMCRA, mountaintop removal coal mining is also supported by federal appeals courts, which have overturned two notable cases that sought to make MTR illegal, or more specifically, valley fills, which compromise Clean Water Act mandates.

The first case, Bragg vs. Robertson, filed in 1998 by attorney Joe Lovett, charged the Army Corps of Engineers and the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) with violating the Clean Water Act by issuing permits for valley fills at MTR operations.20 The plaintiffs were local residents impacted by MTR, including Patricia Bragg, a housewife from Pie, West Virginia.21 In 1999, Federal District Judge John Haden ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, agreeing that valley fills violated the Clean Water Act. This decision sent shock waves into the coalfields of West Virginia, prompting state senators Robert Byrd and Jay Rockefeller to draft a rider to an appropriations bill nullifying portions of the ruling.22 Ultimately, Bragg vs. Robertson was appealed by coal companies, and in 2001the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Haden’s decision by arguing that the case should be tried in state court, and citizens did not have the right to sue state regulators over a failure to enforce the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act.23

Similar litigation was pursued again by Joe Lovett in 2005 when a suit against the Army Corps of Engineers was filed on behalf of three state environmental groups: the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, the Coal River Mountain Watch, and the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy. This case charged the Army Corps of Engineers with improper permitting processes of MTR operations. In 2007, US District Court Judge Robert Chambers ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and cited the Corps with failure to meet the standards of the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.24 This ruling required more-stringent environmental reviews of MTR, but was overturned in 2009 by the Fourth District Court of Appeals, which claimed that the US Army Corps of Engineers had the authority to issue Clean Water Act permits for MTR operations without extensive review.25 In between these two legal actions by citizens and state environmental groups, the Bush administration sought to simplify the regulatory process of mountaintop removal by redefining the concept of waste to “fill” material, rendering the use of valley fills legally permissible in 2002.26

Currently, the Obama administration promises tighter enforcement of the Clean Water Act in regard to MTR and greater regulation of the mining permit process, but refuses to place a moratorium on mountaintop removal coal mining. In April 2010 the EPA issued the first comprehensive guidelines to protect communities from the impacts of MTR, “using the best available science and following the law.” The newly established “comprehensive guidance” set “clear benchmarks for preventing significant and irreversible damage to Appalachian watersheds at risk from mining activity.”27 When presenting the regulatory framework, EPA director Lisa P. Jackson said, “The people of Appalachia shouldn’t have to choose between a clean, healthy environment in which to raise their families and the jobs they need to support them. That’s why the EPA is providing even greater clarity on the direction the agency is taking to confront pollution from mountaintop removal.”28 Interestingly, like coal industry officials, the EPA often refers to MTR as “mountaintop mining,” omitting the more descriptive and apt word “removal” when referring to the practice.

Despite the rhetoric of tighter enforcement and regulation over this type of coal extraction, in June 2010 the EPA approved its first MTR mine under the new guidelines: Arch Coal’s Pine Creek Mine in Logan County, West Virginia, a 760-acre MTR operation containing three proposed valley fills.29 Environmental groups and activists were displeased with the decision, expecting more from the Obama administration’s environmental protection agency. However, in 2011 the Obama EPA did revoke the permit for the Spruce No. 1 Mine in Logan County, the largest proposed MTR operation to date, signifying a major victory for the anti-MTR movement.30 Despite this regulatory success, Maria Gunnoe, Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition community organizer and 2009 recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize, objects to the regulation of mountaintop removal coal mining:

I will never believe that they can regulate, in any way, shape, form, or fashion, doing MTR or filling valley fills. I think it’s impossible to regulate doing that. “Regulate,” in my opinion, is a way to find excuses for it, and there is no excuse for doing it. . . . They mislead people into thinking that since these words are on paper that this just isn’t happening anymore, and that’s not the case.31

When the regulatory guidelines were initially released, and the Pine Creek Mine was approved under the new rules, Amanda Starbuck, a representative of the international environmental organization Rainforest Action Network, also voiced objections:

This is a devastating first decision under guidelines that had offered so much hope for Appalachian residents who thought the EPA was standing up for their health and water quality in the face of a horrific mining practice. . . . The grand words being spoken by Administrator Jackson in Washington are simply not being reflected in the EPA’s actions on-the-ground. This continues the inconsistent and contradictory decisions that have plagued the EPA’s process on mountaintop removal coal mining all along.32

Environmental groups continue to pressure the administration in hopes that MTR will cease in central Appalachia. Local activists repeatedly invite Lisa Jackson to the coalfields to see an MTR site firsthand. At the time of this writing, she has ignored all requests.

Environmental Justice, Gender, and Anti–Mountaintop Removal Activism

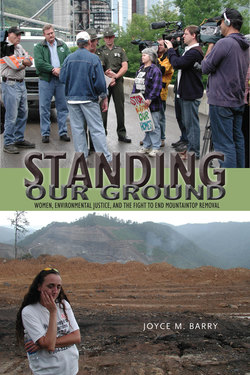

Standing Our Ground: Women, Environmental Justice, and the Fight to End Mountaintop Removal is fundamentally an examination of women’s environmental justice activism in the anti–mountaintop removal coal mining movement in West Virginia. The working-class white women and Cherokee women profiled in this book have ties to coalfield communities and have been directly impacted by the rise of MTR in West Virginia. Some have lost their homes and been forced to relocate, while others fight to stay in their homes and communities. While the book trains its analysis on West Virginia women’s participation in this movement, and the voices of these coalfield women are contained throughout the manuscript, this is not an ethnographic study. Ultimately, this book is an interdisciplinary cultural studies examination of the environmental justice movement against MTR. Even though I focus attention on those most directly affected by Big Coal, the women contained in these pages are not the only ones working tirelessly for environmental justice in the central Appalachia coalfields. Women such as Vivian Stockman, Diane Bady, and Janet Keating have committed their professional lives to coalfield justice through their work in the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. In fact, chances are that if you view a picture of an MTR site contained in books, magazines, or newspaper articles, it was taken by Vivian Stockman.

There are other women, too, such as Sandra Diaz, Steph Pistello, and Mary Ann Hitt, who speak out against MTR and engage in lobbying efforts within the coalfields and in Washington, DC. Also, Teri Blanton, member of Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, has been active against Big Coal for years now. Ann League is fighting MTR in Tennessee as part of the Save Our Cumberland Mountains organization, Jane Branham and Kathy Selvage organize against Big Coal with the Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards in Virginia, Elisa Young fights the industry in Ohio as founder of the Meigs Citizens Action Now organization, and Julia Sendor and Debbie Jarrell are members of the Coal River Mountain Watch in West Virginia. And, of course, there are many men working for environmental justice in the coalfields. Men such as Larry Gibson; Bo Webb; Vernon Haltom; Ed Wiley; ex–coal miner Chuck Nelson; Julian Martin, member of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy; and Bill Price, a West Virginia native who represents the Sierra Club in the coalfields, are all on the ground in West Virginia and very active in anti-MTR campaigns. In fact, Judy Bonds noted that the gender composition of the movement has changed from the late 1990s. She acknowledged that “as the movement has become bigger, and more people have become involved in this, more men have stepped up to the plate. . . . It’s very much needed and appreciated that the men are starting to become more involved, and in that way it diversifies the movement.”33

Indeed, the movement to end mountaintop removal coal mining in central Appalachia is diverse, and since the late 1990s has grown tremendously. What began as a purely local issue in the coalfields of Appalachia has become a regional, national, and international campaign to end this destructive form of coal extraction. The movement involves people from all walks of life: housewives, former coal miners, professional environmentalists, high school and college students, musicians, academics, scientists, actors, filmmakers, and many others who are compelled to work for environmental justice in Appalachia. However, this work argues that MTR became an environmental justice issue through the tireless work of primarily women dealing firsthand with the effects of Big Coal in their communities. Coal River Mountain Watch member Sarah Haltom claims that in her experience, women are more vocal and less afraid to speak out than men in the movement, and “tend to see the issue with more urgency than men.”34 OVEC community organizer Maria Gunnoe claims that “women are the ones who began this movement, and I think it’s because we recognized what it was doing to our kids.”35 Gunnoe recalls a 2003 meeting where twelve women discussed MTR and strategies for fighting Big Coal: “There was a lot of women around that table when we decided, no compromise. . . . It has to be stopped.”36 Women’s activism in the coalfields put this issue on the map, so to speak, and my work highlights their participation and centralizes gender in environmental justice theory and praxis.

Discussions of environmental justice, and the ways in which it differs from mainstream environmentalism, are numerous and well-established in the EJ canon.37 Environmental justice began in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the United States, and was birthed by the civil rights movement.38 Environmental justice seeks to highlight the ways human injustices based on race, gender, class, nation, and so forth are connected to environmental problems. It differs from mainstream environmentalism in that it defines the environment as where we “live, work, and play,” complicating the long-standing conception of the environment as remote wilderness infrequently touched by humans.39 Conversely, EJ emanates from human communities and concentrates on improving and preserving those communities in the face of industrial incursions. Environmental justice operates from the assumption that poor people occupy poor environments, and it seeks justice for vulnerable human populations and the natural spaces that house them.

In particular, EJ argues that minority communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental pollution and resource depletion, and community members often form or join collectives that fight for political, economic, and environmental remediation.40 EJ scholar Filomina Chioma Steady argues that environmental justice has “inspired movements that challenge environmental racism all over the world, especially in the African Diaspora and in Africa and has appealed mostly, though not exclusively, to people of color, indigenous people, and poor people in endangered environments.”41 Indeed, environmental justice scholarship has focused primarily on race and class because of its origins in communities of color. This manuscript applies EJ scholarship and actions rooted in communities of color to primarily white, working-class coalfield communities in West Virginia, expanding the elastic purview of EJ. In addition, I centralize gender in environmental justice thought and practice by focusing on women’s participation in the anti-MTR movement.

Feminist political ecologists argue that women have a unique connection to environmental issues, not based solely or exclusively in biology, but primarily in the work they perform in their homes and communities. Because women are often responsible for providing and managing life’s basic necessities, such as food, clothing, child care and elder care, they view environmental problems in unique ways. Dianne Rocheleau argues that these responsibilities put women “in a position to oppose threats to health, life, and vital subsistence resources, regardless of economic incentives, and to view environmental issues from the perspective of home, as well as that of personal and family health.”42 As examined in parts of this book, some feminists argue that this particular connection to home, community, and environment precipitates women’s large numbers in environmental justice groups in the United States and beyond. West Virginia women active in the movement to end MTR are representative of the formidable presence of women in environmental justice groups. Regardless of the community, or the environmental justice issues at hand, women, working-class white women, and women of color form and join EJ groups in large numbers.43

Even with women’s undeniable presence in environmental justice practice, much of environmental justice scholarship fails to analyze and include gender in its analysis in substantial ways. Nancy C. Unger suggests that “while race and class are regularly addressed in environmental justice studies, scant attention has been paid to gender,” but “women’s responses to the ever-shifting responsibilities prescribed to their gender, as well as to their particular race and class, have consistently shaped their abilities to affect the environment in positive ways.”44 Women in West Virginia, like many women in EJ groups throughout the world, transform work associated with the private sphere into public, community-based activism. In doing so, they show the importance of women’s influence in both the public and the private sectors of society.

Chapter Summaries

Chapter 1 examines the material conditions of West Virginia women in this age of mountaintop removal coal mining, guided by the assumption that in searching for solutions to the political, economic, and environmental problems associated with MTR and Big Coal in the state, the perspectives of poor and working-class women must be considered. This focus is important, given that it is poor, rural women (nationally and internationally) who not only bear the costs of uneven political and economic conditions, but who form or join collectives to fight injustices in their communities. In discussing the material conditions of women in West Virginia, this chapter examines how gender ideologies have been shaped by the coal industry, and how women’s participation in the anti-MTR movement simultaneously embraces and defies traditional gendered prescriptions.

Chapter 2 places the anti-MTR movement, and women’s participation, within the context of environmental justice activism in the United States. The EJ framework provides a productive way to assess the anti-MTR movement because of its historic focus on the connections between adverse environments and disenfranchised human populations. Environmental justice links social justice—economic, political, and cultural—with the natural world, exposing the root causes of both environmental problems and social inequity. This chapter reviews EJ’s historic focus on race and class, but, more important, centralizes gender in this analysis of the movement to end MTR and Big Coal’s influence in West Virginia. EJ has done a tremendous job of emphasizing the importance of class, social justice, and vulnerable communities’ connections to the environment, but, as indicated above, insufficiently assesses the role of gender in EJ thought and practice. Too often the tireless efforts of women EJ activists are not fully examined by environmental justice scholars, even though working-class white women, and women of color, participate in these movements in large numbers.

Chapter 3 situates West Virginia women’s environmental justice activism in the anti-MTR movement within the history and culture of grassroots protest in Appalachia. Historically, women in the region have joined coal industry reform efforts such as labor strikes and unionization campaigns. Women were also active in anti-strip-mining activism of the 1960s and 1970s. Women in the anti-MTR movement, unlike previous instantiations of women’s activism, envision a life without coal in central Appalachia, focusing their efforts on creating economically and environmentally sustainable communities. In doing so, they promote a vision of West Virginia that sees the mountains as inextricably tied to the area’s culture and history. They highlight this connection, while supporters of Big Coal argue that coal, and not mountains, is the defining marker of West Virginia’s cultural history.

Chapter 4 examines racial constructions inherent in the popular anti-MTR slogan “Save the Endangered Hillbilly,” positioning this call within white studies scholarship and as a directive to mainstream environmentalism, which has historically separated humans from the nonhuman environment. The culturally derogative term “hillbilly” has a long history in this country, and is a descriptor used both racially and in terms of class in American society. Activists in the anti-MTR movement reclaim this pejorative term and use it to foster a sense of pride in coalfield residents. In their embrace of “hillbilly,” they mark themselves by race and class in their efforts to preserve the culture and environment of West Virginia in this age of mountaintop removal coal mining.

Finally, chapter 5 situates mountaintop removal coal mining, and the movement to end it, within the global context of neoliberal economic transformations, global energy, climate change, and environmental justice protest. Appalachian activists realize that the adverse impact of MTR does not remain in the isolated mountainous communities where coal is extracted. Coal provides half of this country’s electricity, and is, indeed, the primary source for electricity generation in the world, but emits the largest amount of CO2 into the earth’s atmosphere, contributing greatly to climate change. With this knowledge, grassroots Appalachian activists are concerned with making global environmental justice connections in their efforts to end MTR. These activists work with the realization that while they are all rooted locally, they are socially and environmentally connected to the world at large.