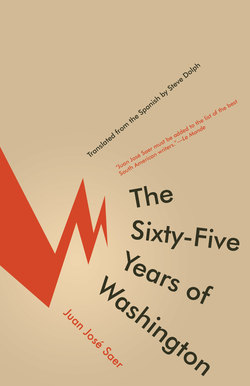

The Sixty-Five Years of Washington

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Juan José Saer. The Sixty-Five Years of Washington

Отрывок из книги

Praise for Juan José Saer

“Juan José Saer must be added to the list of the best South American writers.”

.....

Leto doesn’t laugh now. The word radiotelephonic carries, as though pasted to its reverse side, the image of his father: but sadness isn’t what has erased the smile from his face, but rather that somewhat mechanical gravity we assume when, with its insistent call, a thought or memory lures us toward the internal. For a few seconds, the Mathematician’s narration, intense and highly detailed, becomes, little by little, loose words, sound without meaning, a distant murmur, as if, despite the identical rhythm of their walk and of their almost grazing arms, they are walking in dissociate spaces, proving how much a memory can separate two people until, finally, the call dissipates, not without leaving a vague pit inside him, like a stain on a white wall whose source you ignore, and eventually Leto smiles and becomes attentive again, and the words of the Mathematician who, as I was saying, no?, is telling Leto about Washington Noriega’s birthday, emerge from the horizon of sound and continue filling his head with not always adequate images. And the twins . . . says the Mathematician. They leave the sidewalk; a car stops at the corner, waiting to turn off San Martín; they hesitate, move around it, cross the intersection, which unlike the previous ones is paved and not cobblestone, and reach the opposite corner. They leave behind the sunlit street and continue under the shade of the trees. Since stepping into the street the Mathematician has been quiet, postponing what he was about to say and assuming a vigilant expression at seeing the car approach, an air of ostentatious hesitance when the car, stopping at the corner, blocks their path, and when they leave the car behind his hesitant air gives way to a distracted and reproachful shake of the head, which stops when they reach the opposite sidewalk. The Garay twins, Leto goes on thinking. The twins, continues the Mathematician when they enter the shade, had gotten a hose to install a keg of import. In the hypothetical courtyard, situated in a fantastical place, the human figures, simplified by Leto’s imagination, disperse and scatter, active, outlined against the twilight: the Centaur, Basso’s wife and their girls, Botón and Basso picking vegetables at the back, the twins installing, at the door to the kitchen, the keg, covering the hose with ice, and Noca’s carriage leaving for the coast by a sandy road that Leto and Barco once walked, three months before, on a Sunday morning, to fish. And while the Mathematician dispenses new names, the image, more or less stable, made of assorted memories, is populated by new figures who come to occupy a place and function: Cohen and Silvia, his wife, Tomatis and Beatriz, Barco and La Chichito—the Cohens have come on their own—and Beatriz, Barco, and La Chichito, who had gone to pick up Tomatis at the paper, where he came out with a stack of day-old newspapers, for wrapping up the fish on the grill. According to Basso or Botón, says the Mathematician, Marcos Rosemberg had brought wine the night before, twenty-four bottles, and was in charge of going to find Washington and taking him to Basso’s. Finally they arrive, just before nightfall; Marcos Rosemberg’s sky-blue car parks in front of the ranch. To be exact, the Mathematician only says, in Marcos Rosemberg’s car, but since Leto knows it, having gotten in three or four times, he imagines it the proper color, so that he sees, in the twilight, the sky-blue car arrive, undulating and quiet, shimmering slightly in the falling light, in front of the imaginary ranch. They gave him a prodigious welcome, says the Mathematician ironically, quoting Botón verbatim. Evidently, the tap to the keg was poorly installed—it came out all foam—so Barco, who is a genius with his hands, dismantled and reinstalled the tap. Is it working? Is it? inquired a circle of anxious faces. Finally it started to draw. Because it would cool off that night, they’d prepared a large table, which hadn’t been set, under the pavilion, near the grill. Overcoming a moment of confusion, Leto is forced to install the unforeseen pavilion among the trees at the back. Nidia Basso and Tomatis were making a bitter salad in the kitchen. Cohen, the psychologist, who was going to be the cook, was lighting a fire in the grill. Barco was filling glasses with beer, and Basso cut slices of strong cheese and mortadella on a board and passed it around. Beatriz was rolling a cigarette. Washington, who had just relieved himself of his old Aerolinas Argentinas bag, which was full of books and papers, held a glass of beer in his hand, without deciding to take the first drink. And Botón? Botón, for hours, seemed to have removed himself from his story, as if the role of observer precluded his intervention in the action. Introducing a subtle variation, the Mathematician comments that, in fact, Botón’s version of events demands, with Botón’s personality in mind, a continuous revision, aimed at translating the scene from the province of mythology to that of history, but Leto, right then, from beneath the persistent image of a courtyard on the coast, on a winter evening, full of familiar and unfamiliar faces that combine vaguely, Leto, I was saying, no?, almost without realizing it, and even though it’s always the same, is thinking about another time, about Isabel, the incurable illness, about Lopecito saying next to the closed casket, his eyes full of tears: Your old man was a television pioneer. He had the inventor’s gift. I owe him everything.

—The idea to celebrate his sixty-fifth birthday was the twins’, says the Mathematician. And you have to tip your hat to them for bringing together such a diverse crowd. But as the saying goes: not everyone there was someone nor was everyone who’s someone there.

.....