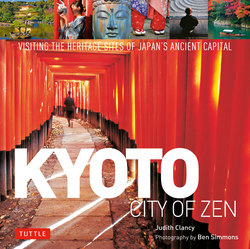

Читать книгу Kyoto City of Zen - Judith Clancy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

INTRODUCING KYOTO

Below a calendar depicting the garden within, a pair of modest zori thong footwear sit on a shelf in a temple’s entrance.

*See district maps on pages 66 (Northern Kyoto), 96 (Western Kyoto) and 122 (Southern Kyoto) for sites outside this map.

KYOTO’S MAIN HERITAGE SIGHTS

CENTRAL AND EASTERN KYOTO

1. Kyoto Imperial Palace, page 36

2. Nijo Castle, page 40

3. Heian Shrine, page 42

4. Downtown Kyoto, page 46

5. The Gion District, page 50

6. Kiyomizu Temple, page 54

7. Kennin-ji Temple, page 58

8. Nanzen-ji Temple, page 60

NORTHERN KYOTO

9. Ginkaku-ji, page 68

10. The Philosopher’s Path, page 72

11. Shisendo Temple, page 76

12. Shugakuin Imperial Villa, page 78*

13. Shimogamo Shrine, page 80

14. Kamigamo Shrine, page 80*

15. Daitoku-ji Temple Complex, page 82

16. Mount Hiei, page 86*

17. Enryaku-ji Temple, page 86*

18. Kurama Village, page 88*

19. Ohara Village, page 92*

WESTERN KYOTO

20. Kinkaku-ji Temple, page 98

21. Ryoan-ji Temple, page 102

22. Ninna-ji Temple, page 106

23. Myoshin-ji Temple, page 108

24. Arashiyama, page 110

25. Sagano Village, page 116

26. Takao Village, page 118*

SOUTHERN KYOTO

27. Tofuku-ji Temple, page 124

28. Fushimi Inari Shrine, page 128

29. Saiho-ji Temple, page 130

30. Katsura Imperial Villa, page 132

31. Daigo-ji Temple, page 136*

32. Byodo-in Temple, page 138*

33. Ujigami Shrine, page 140*

34. Genji Museum, page 140*

INTRODUCING KYOTO

For thousands of years, footsteps have smoothed this land. First barefooted, then wrapped in straw or raised on wooden clogs, feet continue to pat down mountain trails and river banks, divide orderly rows of vegetables, meander through stately gardens, mount temple steps, thread alleyways and stroll along concrete sidewalks. The feet that strode these passageways span centuries, encompassing tradition and modernity. Today, feet shod in sneakers, children’s shoes sporting cartoon characters, British oxfords and Italian stilettos, or kimono-clad citizens in elegant zori, impart their signature tone and tempo to the city.

The home of seventeen World Heritage Sites, over a thousand temples and shrines and some of the world’s most beautiful gardens, Kyoto now resonates with the footfall of appreciative tourists.

Framed within cinnabar red shrine gates, a Shinto priest in formal headgear and silk robes invokes the resident gods of Yoshida Jinja, a shrine founded in 859.

The sun casts a long elegant silhouette on a stone-inlaid lane in the Miyagawa geiko district.

Beautifully attired in colorful summer cotton yukata, young women gather before Kyokochi Mirror Pond at the Golden Pavilion. A World Heritage Site, the estate became a Buddhist temple in 1422, but the stroll garden surrounding the pond and pavilion remains much as it was 1,000 years ago when property of a court aristocrat.

Raised stepping-stones in the garden of Okochi Sanso entrancingly lead one to the rustic, yet elegant Tekisui-an teahouse on the estate of the late film star, Okochi Denjiro (1898–1962). The stones are deliberately spaced to slow the visitor in the approach to the teahouse, allowing one to savor the scenery. The infinity-shaped pathways farther on lead to a garden the actor designed for meditation.

Toyokeya, a neighborhood tofu and yuba shop, located near Kitano Shrine.

A traditional toro stone lantern stands at the edge of the garden pond (with a reflection of the wooden five-storied pagoda) amidst autumn foliage at Toji Temple, a World Heritage Site.

The vast gravel courtyard fronts the immense Founder’s Hall (Goei-do) of Higashi Hongan-ji temple in the vicinity of Kyoto Station. Founded in 1602, it is one of two head temples for the Jodo Shinshu Sect of Pure Land Buddhism. The building supports a roof of 175,000 clay tiles making it one of the world’s largest wooden structures.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF JAPAN’S ANCIENT CAPITAL

The city of Kyoto began to take shape in the 8th century when some of its earliest residents, the Hata family, invited the Emperor to make his home on their hunting grounds. Under the most rigorous dictates of geomancy, planners created a grid of roads patterned after the western Chinese city of Xi’an, terminus of the Silk Road.

Rich with game, traversed by rivers and sheltered on three sides by mountains, Kyoto began its transformation into one of the great cities of the 9th century. By the late 800s, the network of avenues and byways had become the new Imperial Capital. Workers who lived in rough huts helped build a palace and estates for the nobility. A political court thrived on ritual, bureaucratic intrigue, poetry and the newly introduced spiritual practices of Buddhism, a faith introduced to the former court in Nara.

Molded by deep religious beliefs and rent by warring factions, Kyoto began its journey through history, not only as an imperial stronghold but also as a vibrant residential city, with enclaves of astute merchants, gifted artisans and hard-working commoners who lived alongside the temples, shrines and gardens that even today stand as tributes to the skills and ancient aesthetics of their creators. But as much as Kyoto is rich with remnants of a remarkable past, it is a forward-looking city, as embodied in the architecturally stunning and massive Kyoto Station.

Kyoto is also a city festooned with ugly electric wires and burdened with lumpish apartment buildings, intrusive sidewalk notices and gaudy neon signs. Discarded bicycles lie in gnarled mounds. For while Kyoto residents are truly proud of their city and its historic artistic legacy, some have perfected enough selective vision to overlook aesthetic insults.

Some would say that it was a series of historical accidents that allowed Kyoto to become one of the world’s metropolitan jewels. Other would argue that it could have been no other way. In 1868, after the Meiji Restoration, the Emperor and his court, as well as the heads of prestigious families, moved from Kyoto to the new capital of Tokyo, then a collection of rural towns known as Edo. Despite fear that losing its status as the capital would pitch Kyoto into decline, it thrived. The city is not only a stronghold of tradition but early on embraced progress. In 1890, it built one of the country’s first large-scale engineering feats, a canal that allowed rice from the agricultural prefecture of Shiga to be shipped efficiently into the city. Kyoto also quickly established hydroelectric power, realigned streets to allow construction of a railroad station and boasted the country’s first tramcar.

The members of the oldest families who remained behind founded Nintendo, Kyocera, Murata Manufacturing and Shimadzu Corporation, now among some of the world’s leading companies, while Kyoto University boasts of Nobel Prize recipients in chemistry and physics.

The top-knotted head of a warrior bowing to the Emperor.

The Imperial chrysanthemum motif on a gate at Shoren-in Temple.

The blossoming of spring along the Eastern Mountains.

The straw sandal shod feet of Kukai, the 9th century monk who founded the Shingon sect of Buddhism in Japan.

Young musicians aboard the magnificent Naginata Float during the Gion Festival.

A literary tradition of poetry writing outings was one of the pleasures of the 10th century Heian court, as depicted in this painting of nobles seated along a meandering stream.

Tiger motif walls.

Painting of courtiers on horseback.

Stone image of a demonic figure supporting a great weight.

ZEN

BUDDHISM AND THE TEA CEREMONY

Zen was the last Buddhist sect to enter Japan, and by the 14th century one that had a profound influence on the arts: calligraphy, Noh drama, architecture and especially the tea ceremony.

Zen is based on meditation, a practice in which one looks into the source of the mind, leading to an inner equilibrium between the secular and the sacred and, hopefully, enlightenment. Some claim that Zen is more a discipline or philosophy than a religion, but 1,500 years of Zen writings reveal it to be one of the world’s great spiritual traditions. Unlike conventional religion, with a transcendent deity outside of the self, Zen believes that the essence of mind is innately enlightened, and that seeing into one’s Buddha nature is possible through meditation. It was largely as an aid to meditation and good health that Eisai, the Japanese monk who introduced Zen to Japan, brought tea seeds back with him from China and promoted the drinking of tea. Use of the beverage spread quickly among the priesthood and the ruling classes.

A Buddhist/mendicant monk awaits alms from passersby.

The wall of a Buddhist monastery hung with straw hats and sandals.

Neatly placed footwear rests in a temple entrance of pleasingly symmetrical lines of wood, stone and tile.

Two dragons, one clutching the sacred jewel in its five claws, soar through the vaporous mists on the high ceiling of a Buddhist temple, Kennin-ji.

Monks standing in repose before being received into a temple.

After being taken up by the aristocracy, the drink became a privilege of a rising wealthy class. In the late 16th century, the tea master, Sen-no-Rikyu, started to refine the art of making tea into a ceremony, stipulating that all who entered his teahouse were equals to share in the pleasure of a simple bowl of whisked powdered green tea. This was a revolutionary idea, since Japanese society was rigidly class-bound. Thereafter, the tea-room became a meeting ground for priests, artisans, merchants and aristocrats, a singularly powerful cultural statement.

Perhaps this is one reason that Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a common foot soldier who rose to the rank of warlord, was attracted to the tea of Sen-no-Rikyu. The warlord became a patron of this famous tea master, recognizing Rikyu’s influence on society and his undisputed ability to create new aesthetic standards. Artists were inspired to create utensils that embodied these aesthetics, and tea enthusiasts vied in collecting new pieces. During one military excursion in the 16th century, Hideyoshi invaded Korea and brought back Korean potters to reproduce the simple rice bowls that are still highly sought after. Imparting the softness of human touch, the bowls rested lightly in two hands, their thick walls warming but not scalding. Senno-Rikyu recognized beauty in bowls shaped by an expert eye and glazed in soft tones—the pinnacle of graceful simplicity. The Japanese eye has become trained to recognize rustic beauty (wabi), elegant simplicity (sabi), understated tastefulness (shibui) and vague mysteriousness (yugen), a deep response to the passing of beauty (aware) or refined sophistication (miyabi), as a few examples of the many expressions still in the aesthetic lexicon that concern tea utensils.

Consequently, most teahouses have rustic settings. Some even have thatched roofs and all have simple unadorned clay walls, a hearth or hanging kettle, an alcove for a hanging scroll, a simple flower arrangement and tatami mats. For Japanese to slip through the low door, sit quietly while listening to the low hiss of the kettle sounding like the wind through the pine trees, is a return to the heart of their culture, a respite from the demands of modern life and its interruptions. It is a journey back to their cultural identity.

Preparation for a winter tea ceremony begins with setting the iron kettle into a sunken hearth.

A tea master carefully ladles hot water into a soft-fired Raku tea bowl.

A guest closes the shoji paper window set within a black-lacquered cusped frame in this tea ceremony room. Ornamentation is kept to a minimum, with a hanging scroll in the alcove and a single seasonal bud.

With an outstretched palm, a guest receives the whisked green tea from a kimono-clad hostess.

The shadows of autumn reflect on a single bowl of powdered green tea resting on tatami flooring.

Red felt carpeting offers a bit of warmth to winter visitors in this temple. The sweet is first consumed, followed by a sip of slightly bitter powdered green tea.

KYOTO’S AMAZING ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE

Japan’s indigenous kami, or gods, live not inside shrines but within the towering cypress trees, sacred springs and waterfalls that surround the buildings. There, in nature, devotees can stand in the spiritual presence of the gods while seeking favor and guidance. The simplicity of a Shinto shrine never competes with its natural setting.

Under Shintoism, Japanese have stood in awe of the power and beauty of nature and the religion’s simple shrines embody this reverence. The torii that identifies a shrine entrance is often constructed by four pieces of timber. These gates invite those closest to the gods, their feathery messengers the birds, to sit on the cross-beams, ready to wing supplicants’ prayers heavenward.

Temples are an entirely different affair. When Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 6th century, Japan, still without an alphabet, relied on written Chinese to convey the tenets of religion, law and philosophy. Scholars, diplomats and artisans were invited to the Nara court (60 kilometers away) to impart a culture distinctly different from—and admired as superior to—Japan’s. With its sophisticated philosophy and texts, Buddhism immediately appealed to Japan’s courtiers who controlled the privilege of literacy, but the religion rapidly reached even illiterate peasants and merchants.

The Chinese adaptation of the Indian religion brought new dimensions of the understanding of the universe and life beyond this one. This new theology was not grounded in the immensity of a cypress tree or the roar of a waterfall. It demanded human-made artifacts: a written text, a myriad of implements, statuary and, grandest of all, huge structures to accommodate believers.

By 596, temple construction had begun. Chinese carpenters were invited to Nara and introduced their techniques to a wonderstruck population. The temples we see today in Kyoto, although fairly faithful descendants of Japan’s 6th–10th century originals, differ greatly from those still in existence in China. Japan’s climate and earthquake-prone land made elevated buildings a necessity. Its rich supply of zelkova, cypress, oak and cedar forests lent itself to increasingly mammoth worship halls as the population embraced the comfort of salvation within a Buddhist paradise.

The vermilion doors of Jikido Hall at Toji Temple, a World Heritage Site, glow in the sunset.

Elaborate metal fret-work marks the eaves of the sloping cypress bark palace roofs. The Imperial chrysanthemum crest and multilayer roof tiles denote the building’s imperial status.

The Phoenix Hall at Byodo-in Temple, a World Heritage Site.

Billowy cherry blossoms and fresh green pines frame the gleaming gold-layered Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji).

A late afternoon visitor poses under the gigantic gate of Nanzen-ji Temple.

Walls are works of art as well as enclosures. The layered earthen clay is interlaced with flat tile work inset with a single rounded tile.

The iconic face of Kyoto streets is its townhouse (machiya). In keeping with neighborhood expectations, Starbucks has opened a branch in a renovated old machiya along the cobblestone slope of Ninenzaka.

A feline resident of the Pontocho geiko district seeks entry into a typical townhouse characterized by a wooden lattice (koshi) frontage, curved bamboo fencing (inuyarai), clay rooftiles aligned in a one-stroke design (ichimonji), and short curtain (noren) that indicates that the shop is open for business, perhaps even furry ones?

Many traditional old homes still exist in the southeastern district of Daigo. Late afternoon sun imbues the wooden structure with warmth.

Not only did places of worship begin to be shaped in Kyoto, but some of the world’s greatest collections of Buddhist images are found here. One of Asia’s most iconic forms, the pagoda, continues to pierce the ancient skyline, serving as a reliquary for Buddha’s remains and as a revered landmark for Kyoto residents.

Abundant forests have long provided Kyoto with wood to build massive temples and the houses of commoners’ alike. The understated beauty that defines the Kyoto townhouse, the machiya, owes much to its reliance on wood, with its rich palette of hues and variety of grains, which residents lovingly buff until the surface gleams. The glow of well- cared-for wood is enhanced by the plaster and earth that form the machiya walls, the paper windows that shield inhabitants from cold, and the woven straw tatami mats that cover most floors.

Much of the present-day iconic design of these townhouses dates from the great Temmei Fire of 1788. The devastation and the need to quickly rebuild huge swathes of the city led to a uniformity of style that has left its imprint on the city.

The architectural layout of most of the inner-city houses features slatted lattice fronts; open clay “windows”; an inner garden; and a long, narrow kitchen with an overhead skylight to admit light and disperse smoke. The curved bamboo fencing along the roadside wall adds an aesthetic element that cloaks its practical function: it once protected the outer clay walls from damage by spoked cart wheels.

It is no wonder that passersby find the exteriors—the dark-stained wooden fronts, quiet sliding entry doors, and undulating tile roofs—visually soothing. Today, however, because so many machiya are being refashioned into shops, galleries, and restaurants, visitors can also glimpse the inner environments that shaped lives with the quality of their space, texture, and soft light—features that reflect the warm, human sensuality of an organic structure.

In keeping with its commitment to preserving local architecture in the vicinity of Kiyomizu-dera temple, Starbucks kept some traditional elements such as a raised tatamimat area with cushioned seating at low tables and paper sliding windows that suffuse the interior with a soft comfortable light, while also providing chairs in another area.

A flowering potted plum bonsai is an inviting addition to Kimata, a well-appointed traditional inn and restaurant of fine cuisine. The added features of bamboo blinds (sudare) and stone lantern (toro) bespeak of its reputation for hospitality and traditional elegance.

The famed designer, Issey Miyake, opened a shop in a 132-yr-old machiya townhouse located on Yanaginobanba Street in central Kyoto. The simple lean lines of the traditional architecture and attractive courtyard garden complement the design sense of the clothing line within.

UNIQUE KYOTO FOOD TRADITIONS

Traditional Japanese cuisine, especially that of Kyoto, is one of the most sophisticated food cultures in the world. Kyoto’s rich food culture dates back a thousand years, with today’s chefs drawing on centuries-old records detailing ingredients and techniques. Specialized food for the old Imperial court and, later, wealthy merchants, was presented, as it still is today, in bite-sized pieces easily handled with chopsticks. Often served cold, it was accompanied by a hot soup and rice.

The fields of Kyoto boast several distinct vegetables, collectively called kyo-yasai. Kyotoites are very familiar with their local produce, and accord it a place of honor in exclusive restaurants and in the homes of discerning epicures.

The soy product tofu is a Kyoto specialty. It is made by soaking dried beans overnight in good quality well water, churning them into a smooth mash, straining and then boiling the resulting soy milk, and adding calcium sulfate to act as a coagulant. The mixture is then poured into block molds to set.

Tofu adopts itself to a variety of dishes. Smooth silky tofu (kinu) is served cold in summer with a dab of grated ginger. A firmer type, momen, is often cut into cubes, simmered in a kelp broth, and then scooped out and dipped into a light soy-flavored sauce. In addition to plain tofu, many of Kyoto’s supermarkets as well as the food courts found in the basements of department stores sell tofu flavored with sesame seeds, black beans or shiso (perilla).

Another unique Kyoto soy-based food product is yuba, the film formed on the surface of boiled soy milk. The thin, translucent beige sheets are hung, and then sold dried or fresh. The taste is a delicate, slightly sweet concentrate of soy milk. Yuba accompanies many a Kyoto dish, especially in the multi-course kaiseki meal served in better restaurants.

Although it is the gourmet epitome of Kyoto cuisine, kaiseki grew out of the simple meal served at a formal tea ceremony. The present-day kaiseki meal developed in the 16th–17th centuries as the merchant class gained wealth and sought out rarified ingredients and preparations to impress prospective clients.

While delicious, kaiseki’s most striking characteristic, however, is what meets the eye. Moritsuke, the artistic arrangement of food, is an art form in itself, and the dishes on which the food is served are a critical component. For example, the chef will consider color and texture and perhaps even reference the food to flowers or poetry. Presentation is so highly regarded that diners often whip out their cell phones to photograph the dish before them, perhaps to show their friends or to relish in memory the anticipation of culinary pleasure—before a single taste! Then comes the pleasure of uncovering the different dishes as one would unwrap a present, each course a delight to both eye and palette, each a culinary gift.

The White Plum Inn is accessed by a narrow bridge across the Shirakawa River. The delicate interior lighting of the shoji paper doors is one of the refined features of inns and restaurants along this section of the river.

A diner gracefully lifts thin strands of noodles to dip into a soy-based broth.

The colorful selection of lightly pickled vegetables signals the end of a traditional meal.

Old roads that led out of Kyoto to mountain passes had rest stops for pilgrims to enjoy a final repast before setting out. This famous inn is in the Arashiyama area in western Kyoto.

Multi-courses of elaborately presented meals are served on a selection of ceramic dishes, lacquered bowls and sometimes leaves, making the meal as visually pleasing as it is a culinary delight.

Blowfish (fugu) is as expensive as it is occasionally lethal. Chefs must be specially licensed to serve this delicacy, for the liver, when improperly prepared, can be highly toxic.

KYOTO’S EXQUISITE ARTS AND CRAFTS

The variety of arts and crafts available to Kyoto residents, the fruit of generations of artists and ateliers, is truly splendid. Surprisingly, the best place to survey the breathe and width of crafts is a department store, notably one of the larger ones: Takashimaya, Daimaru and Fujii Daimaru. The sixth floors are reserved for crafts: lacquer ware, metal utensils, ceramics, bamboo and wooden items, kimono and all manner of woven and dyed items. Exhibition halls and galleries are also an integral part of the stores as are the restaurants on the seventh floors, making department stores mammoth reservoirs of social, culinary and cultural activity, in addition to their primary commercial role.

There are numerous craftspeople practicing their art in the city today, most notably kimono and obi sashes, for rarely does a single person design and make one item. Most are collective enterprises that span many ages and skills. The Nishijin district is filled with businesses that import raw silk, begin the process of dyeing it, encase some threads with gold or silver foil for the obi, sell and repair looms, operate spinning machines, specialize in threading looms—all leading to the production of clothing—and the whole-sellers who line Muromachi Street offering magnificent seasonal showings of their products, for kimono and obi are not mass produced; each is custom designed and made.

Home to the court for 1,000 years, the city attracted its most talented artisans who continue to produce the highly prized crafts of Kyoto. Lacquered paper umbrellas, painted doors backed with gold foil, handcrafted paper- covered tea canisters, paper fans of seasonal motifs and a gorgeously glazed array of dishes produced in the Kiyomizu area along the Eastern Hills, reveal the refinement of its artisans.

Just saying the word “Nishijin” conjures up resplendent images of elegant wear, but the original meaning of the word denotes the Western campsite of a decade-long war. The rivers in Kyoto might be one of the reasons the weaving and dyeing industry settled here, for the Kamo River was often the site of luxurious lengths of dyed silk being washed and readied for the next stage of work. Today, most looms are automatic Jacquard looms, but individual artists still dot the area, especially the fingernail weavers, who spend hours bent over the cloths patiently straightening the weft with ser-rated fingernails, and the obi weavers, who create unique designs either for wealthy clients or performing artists.

Another famous product is Kiyomizu-yaki, ceramics made near the Kiyomizu Temple. Today, the old wood-firing kilns are not allowed in the city, and most production takes place in a ward beyond the Eastern Mountains. Using centuries-old techniques, steady hands apply delicate tendrils of gold enamel glaze before loading the pots into kilns for their last firing. Many shops and galleries along the Eastern Hills (Higashiyama) display fine porcelain and clay products, often with high prices that reflect the work and talent that went into them.

The best-known crafts shop is the Kyoto Handicraft Center, west of Higashi-oji, on Marutamachidori. Items range from simple greeting cards to high-end antiques with a nice representation of woodblock prints, cloisonné, pearls, lacquerware and swords.

Many antique and print shops and galleries are clustered along Nawate-dori, Furumonzen-dori and Shinmonzen-dori, three areas north of Shijo, near the Shinmachi and Gion districts, and along Teramachi, north of Sanjo-dori. A stroll along these streets can be like visiting a museum, but one in which you are allowed to handle the exhibits.

The best artists in the land served the court, and even today the concentration of ateliers makes Kyoto a delight for those with a discerning eye.

Many steps are necessary in producing a kimono. This woman is shading a stretched length of silk to be dyed, one of the early steps in the process.

The art of wearing a kimono involves understanding motifs and color combinations, the dictates of the social status of the wearer and the demands of the occasion. Here, a model pivots on the runway during one of the kimono shows that are featured daily at the Nishijin Textile Center.

A fragrant branch of the blossoming daphne infuses the tearoom with spring.

A busy employee in the textile center answers a customer’s question.

Decades of experience are needed to become a master weaver: an understanding of the textures and colors of the threads to be selected, along with the technical dexterity of managing all the spindles and shuttles involved in producing a single obi.

An exquisite array of dyed silk skeins fills several walls at Kawamura Weavers in Nishijin.

Katsuji Yamade applies hot liquid wax to a length of silk hung across his studio and held in place with bamboo stays. He will decorate the entire length before the cloth is sent to the steamers for fixing the dyes and then to a seamstress for assembly.

A careful selection of colored silk is readied to bring to the loom.

KYOTO’S

AMAZING FESTIVALS

As the men lift a one-ton portable shrine unto their shoulders, they cry out “Hoitto, hoitto” to announce that local gods are on their way. There are few places in the world where communities celebrate festivals as enthusiastically as in Kyoto. These impressive events have evolved into gorgeous pageants laden with cultural richness. Embodied in the festivals’ aesthetic element, is the serious business of appeasing and pleasing the myriad Japanese gods who love to be entertained by their descendants, the Japanese people, who in turn love to celebrate their deities.

Festival time brings a variety of customs that are synchronized in the cultural heart of Kyotoites. Families display treasured heir-looms and offer charms to dispel ill health. Gods are moved from their home shrine to a smaller more distant one. Massive portable shrines are jostled on the shoulders of men, exuberantly shouting hoitto hoitto or solemnly pulled through the capital streets to the musical accompaniment of transverse flutes and bells. Their path is aflutter with kimono sleeves, while sky-high halberts sway in the air above.

The Gion Festival, one the city’s oldest, is now designated an intangible World Heritage. This mid-summer extravaganza culminates in two solemn processions on July 17 and 24. Other activities such as assembling the floats, practicing gion-bayashi music, selecting participants, and preparing offerings all require community effort. Households in each district contribute money for upkeep of the floats and carts, costumes, and attendant expenses. All ages are recruited, from the young boys who sit atop the floats playing instruments, to the men who slowly pull the massively heavy floats through the streets. Another two men stand astride the front of each float giving directions with a delft flicks of handheld fans. Despite the sweltering heat and hours of organizing, participation in this cultural heritage is a coveted honor.

The floats themselves have been transformed into moving museums with heavy European tapestries and ornate lengths of Chinese embroidered silk that traders brought into the county over 400 years ago. To the Japanese artisans and merchants with the prescience to recognize the novel beauty of these imported fabrics, the subtly colored pigments and elegantly fine needlework bespoke different cultures and societies; they conjured worlds inhabited by unknown artists whose skills were revealed through their handiwork.

The Aoi Festival on May 15 is a procession and pageant that takes a whole day to unfold. Glistening black oxen pull black lacquered carriages dripping with wisteria blossoms through the streets of Kyoto. Ladies in ancient court attire sit resplendent inside. Attendants and men dressed as courtiers walk alongside. They all accompany the female messenger of the Imperial court as she bears a greeting to the chief priest of the Kamigamo Shrine. Along the way, the procession stops at the Shimogamo Shrine where “courtiers” in ancient garb display archery skills. They shoot their arrows while perched on wooden saddles set on bedecked and tasseled horses. After a break for refreshment in the shrine, the procession continues through the streets and along the Kamo River. The hypnotically slow pace and the creaky swaying motion of the ox-drawn carts impart an atmosphere of timelessness.

Kyoto’s third great festival, Jidai Matsuri is held annually on October 22. This newer Festival of the Ages showcases Kyoto’s 1,200-year history in a visual display of the city’s position as arbiter of design and tradition. Costumes reflect back a thousand years to when women of the 9th century court donned twelve layers of diaphanous silk kimono. The display extends into the late 19th century, when the appearance of Japanese men in suit and tie signaled the country’s opening to Western fashion, culture, and science.

Even today, the weaving and dyeing industries of Kyoto continue to contribute their artistic acumen in researching and renewing the intricate weaves and dyes that reflects centuries of textile techniques.

In addition to providing a gorgeous entertainment for native and tourist alike, Kyoto’s festive pageantry continues after a thousand years to reassure believers that the gods remain aware of their petitioners’ desire for safety and peace.

Dancing flames and flying sparks electrify the evening sky as Mountain Ascetic monks (Yamabushi) of the Shingon Buddhist sect prepare the coals for the annual fire-walking ceremony in which participants pray for prolonged good health. The summer event is held at Tanukidani Fudomyo-in temple located up an approach steep enough to ably test one’s health and endurance.

Japan’s largest and most popular shrine is Fushimi Inari Taisha, founded in 711, in the southeastern district of Kyoto. On a summer evening of July 21, red lanterns illuminate the shrine precincts during the Motomiya Festival as visitors walk through hundreds of red torii gates to pray for prosperity. The view is of the Roumon Gate.

The month of July is filled with events connected to the Gion Matsuri festival, including processions of massive floats on July 17 and 24 bringing Kyoto’s treasures into public view. Yukata-clad men at the bow of the Ofune Hoko, are pulling the boat-shaped float with twisted straw ropes through the streets. Young boys similarly clad sit on the upper level of the boat performing Gionbayashi music on flutes and cymbals.

A young man in formal festival wear on the morning of a procession. The designs on the clothing identifies to which float the participant is connected.