Читать книгу Paying Calls in Shangri-La - Judith M. Heimann - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Paying Calls

IN NOVEMBER 1958, LONG BEFORE the State Department allowed spouses to take the Foreign Service exam, long before John and I became one of the first so-called tandem couples, I left my country for the first time.

I was accompanying John to his first post: the American Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia. There he was assigned to be an officer in the political section. We both had graduated from college the year before but, unlike John, I was not officially a diplomat and had received no State Department training. I arrived in Jakarta almost totally ignorant of the place where I was going to live for the next three years or why Uncle Sam was sending us there.

In those days before we were all tethered to the Internet, diplomatic pouches sent once in six weeks by sea were our only route for getting personal mail, and international phone calls were out of the question. So I knew I would have to come to terms with what was—like it or not—our new home. The first impression of this new home was not altogether encouraging.

“SEATO Hands off Indonesia” read some of the signs on the trees lining the road from Kemayoran Airport into town. Other signs showed President-for-life Sukarno giving a big kick to a supine Uncle Sam. There seemed to be similar signs and slogans on every spare space on fences and walls along our route.

Looking beyond the lurid posters, I could see in the putrid water of Jakarta’s roadside canals golden-skinned naked women and children bathing downstream from where men were squatting to defecate. I told myself I could not have asked for a greater contrast to the genteel streets of Northwest Washington, D.C.—which I, as a New Yorker, had found a little too tame. Well, I thought, at least Jakarta won’t be too tame.

. . .

Up until a few months earlier, we had assumed we would be sent to Malaya. John and I had met as freshmen and married just after our junior year at college—he at Harvard and I at Radcliffe (which had all its classes except freshman gym with and at Harvard). John had dreamed of being an American diplomat, ideally in Asia, since he was a child; he had dedicated his senior honors thesis, “The Independence Movement in Malaya,” “To my wife Judy who will share the world with me.”

John started his diplomatic orientation course at the State Department the day after we graduated from college. After that, he had volunteered for nine months of Indonesian language training because he knew that the same language was spoken in Malaya. Malaya in those days was a relatively safe, comfortable place where English was widely used. It was a good place, he must have thought, to introduce his wife to living abroad.

Then word came that we were going instead to Jakarta, capital of Indonesia, a disease-ridden, uncomfortable country where little English was spoken and several bloody rebellions were going on. I tried to soften John’s possible disappointment by saying cheerily: “That will be great. I can learn to speak decent French there,” having somehow got Indonesia and French Indochina mixed up in my head. I saw John’s face grow pale. Although he used to joke about the limited horizons of English majors like me, I think it was only at that moment that he realized how truly ignorant of the outside world I was.

Now we were in Indonesia, and John was sitting beside me in the backseat as we were driven in from Kemayoran Airport; he seemed to be taking in everything he saw. I guessed that Jakarta, with its many Chinese shop signs, reminded him of the Shanghai he had known as an eight-year-old in 1940–41, a time when that part of China was not yet in Japanese hands. By now I knew that John’s Shanghai year included the happiest memories of his life with his mother.

His mother, Doris Olsen, was the daughter of a Danish immigrant civil engineer and a no-nonsense Yankee housewife who stayed at home, cooked, sewed, and raised her three girls—of whom Doris was the parents’ favorite. But Doris had scandalized her family by marrying a New York Jew. This was almost as bad as a cousin who married a Boston Irish Catholic. So nobody was terribly shocked when in 1940, nearly a decade later, Doris again threw convention aside. This time it was to accept the invitation from a Chinese actor named Yao, who was her lover at the time, to go back to Shanghai with him and teach English there for a year. She left John’s physician father, Harry Heimann, at home in New York City and took their only child, seven-year-old John, with her.

John had loved his time in China, especially the food. To the end of his life, he preferred a meal based on a bowl of rice to anything else. He also loved having the sense of being inside a brand new world, which Shanghai was in those days—thanks in part to his mother’s dashing friend Yao. Yao was one of the pioneers in bringing Western theater there.

Most of all, I guess, John had loved that, during that time, his mother had seemed happy and fulfilled as he had never seen her before or since. Yao and his modernist friends treated her like a grown-up person and a smart one. But when the Japanese moved to take over Shanghai in 1941, his mother took John home again, on the last American President Line passenger ship not to be torpedoed by the Japanese Imperial Navy.

They returned to John’s patiently waiting father. He loved this brilliant, adventurous woman but did not know how to make her happy. Doris had been one of the first women to pass the Massachusetts bar exam in the early 1930s. But she could not get a law firm to treat her other than as what would now be called a “paralegal.” Fed up, she had quit her job at the law firm and married John’s handsome father Harry. Harry was the son of poor East European immigrants, and had started out at a Hebrew Yeshiva and gone on to do brilliantly at New York City College’s tuition-free medical school. Doris had met him when he was starting his residency at Mass General in Boston. A pioneering scientist of occupational health, but awkward socially, Harry never figured out how to help his wife fulfill her potential in that sexist era.

Unlike me, John was not one to parade his feelings, but it was clear—from the bits of information about his mother he provided me during three years of courtship and two of marriage thus far—that he worshipped her. His worldliness, his sense of what was done and not done in fashionable circles, which served him well at Harvard and beyond, evidently came from things Doris had told him or showed him, even though she was not herself a member of that world. I deduced that she must have been an acute outside observer, a trait her son had inherited. But it would take me decades to realize how much John’s life with his mother would influence his life with me.

Fresh out of the army at age nineteen, John had been spending a year in India with his parents before starting college, when his mother died in Delhi of the long-term effects of alcoholism. His father by then was a Public Health Service officer on loan to the American Embassy to advise the Indian government on health risks to mica miners. Harry had then married a nice widow, the sister of a diplomat at the embassy. In the summer of 1953, John, his father, and his stepmother had sailed back home, crossing the Atlantic on the United States. John (age twenty) and I (seventeen) would meet a month or so later during our first week at college—and fall in love.

. . .

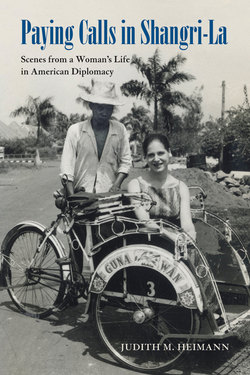

Now, in 1958, five years after that first meeting, the street scene around us after we left Jakarta’s Kemayoran Airport may have reminded John of China and India, but it was brand new to me. We inched along potholed streets that were jammed with vehicles of every description, from oxcarts and horse-drawn carriages to shiny black limousines with license plates showing they were embassy vehicles, such as the car that had collected us. There seemed to be dozens of bicycle rickshaws that John called becaks (pronounced bechaks), with the passenger seated on a bench facing forward, sometimes under a shabby but garishly colored awning, while the barefoot driver sat on a bicycle seat behind, and pedaled.

Slowed to a snail’s pace as they approached the city, all the car drivers were leaning on their horns while the becak drivers rang their tinkling bells. Workmen and peddlers walked calmly down the middle of the crowded street with a long pole balanced on a shoulder or across the back. Each end of the pole was bent down by the weight of a load of rice or fish or raw rubber or small electrical appliances or lumber or firewood.

John’s experience of life overseas and his diplomatic aspirations fascinated me. By age sixteen, I had already known I wanted to be part of a bigger world than I could find within my own country. It must have been already obvious to my New York City high school classmates, who chose for my senior yearbook a verse by Edna St. Vincent Millay to go under my picture: “The world is mine. A gateless garden, and an open path / My feet to follow and my heart to hold.” And then, during my first week at Radcliffe, I met John, fresh from India.

Until the plane trip that brought us to Jakarta by way of Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore, I had never been on a ship or an airplane, much less abroad. But I had lived in Poe’s and Hemingway’s Paris and Conrad’s Africa, Dickens’s England, Eric Ambler’s Eastern Europe and Levant, Somerset Maugham’s Southeast Asia, and Kipling’s India. Those places were as real to me as anything I had seen myself. Looking back on our contemporaries in the Foreign Service of those days, I think we were typical: the husband long interested in a career in diplomacy or foreign policy, the wife ready to go where her husband took her, both of them well-educated and eager for adventure.

When we finally got to the middle of town, the view out the window changed: we were now among nineteenth-century colonial houses in a scene straight out of the stories of Somerset Maugham. I began to be intrigued.

That first day, we were given lunch and much good advice by John’s boss, John Henderson, and his wife, Hester, in their lovely old Dutch colonial house in town, set in a tropical garden. The house had marble floors and massive rooms with high ceilings from which hung 1930s ceiling fans. Hester explained that the old-fashioned charm of the house helped compensate for unreliable electricity, no air-conditioning in the public rooms, and no hot water. She said that less than a year earlier, in December 1957, President Sukarno had expelled the tens of thousands of Dutch who had been living in Indonesia up to then, in her house and others like it.

After lunch, we were driven home—a trip that could take anywhere from a half hour to an hour and a half, depending on the traffic—to one of a row of eight embassy-owned prefabs that had been designed for northern climes. Were it not for the palm trees and the tropical vines that clung to the wire fences, our street could have been in an American postwar mass-produced suburb, such as Levittown outside New York City.

I could reach up and lay my hand against the ceiling of the tiny rooms under a flat, black, tarred roof that absorbed heat when the sun shone and leaked when it rained. The kitchen, with its white enamel kerosene stove and fridge and wooden-faced built-in cabinets, looked almost American. But our embassy guide explained that there was not enough electricity to run a stove or fridge. Thus the need for kerosene.

Fortunately, there was enough power (from a noisy generator next door to our house) to allow all eight prefabs to run a window air-conditioner in the master bedroom. We were advised to keep anything leather in that room. “Otherwise, in three days in this humidity, mold will turn your shoes into blotting paper.” All the windows had screens, shutters, and crisscross security bars as well as venetian blinds, making us feel a bit as if we were living in a miniature fortress.

We were introduced to what seemed to be a lot of servants, mostly inherited from our predecessors, and we changed out of our wilted clothes into fresh ones.

I quickly learned that diplomats in Indonesia in the late 1950s, in addition to having a big domestic staff, were exposed to a variety of dangerous diseases. Chief among these were amoebic and bacillary dysentery, malaria, typhoid, and dengue fever, and, more rarely, polio and tuberculosis. Entertainment consisted of lunches, dinners, and teas at people’s houses. One communicated with friends chiefly by hand-delivered notes. There were occasional engraved invitations to formal dinners and balls on gilded, embossed cards. Even the most informal notes inviting people to supper arrived on folded “informal” cream or white stationery with the hostess’s married name engraved (never printed) in black on the top page. The whole scene seemed vaguely familiar to me, striking a chord in my English-major brain. And then I realized what living as a diplomat’s wife in Jakarta in those days most resembled. It was not so much the 1930s exotic, colonial world of Somerset Maugham as it was the earlier, smaller, class- and caste-ridden world of Jane Austen’s rural England.

The squirearchy that ran our little social world was headed by our ambassador and his wife. Important secondary roles were played by the deputy chief of mission (DCM) and his wife and, in our case, the political counselor and his wife.

International diplomatic etiquette—which had been transmitted without change from the nineteenth century—required that I pay calls on the wives of all the officers at the embassy senior to John, beginning at the top, and then call on the wives of John’s counterparts in other embassies in town. (Whatever their country or language, John’s counterparts at the different embassies in town and their wives had also all been taught to pay and receive calls.)

My first protocol call took place in the Puncak (pronounced poon-chak), a retreat in the mountains, where the air was cooler. The Puncak was two hours away by road from Jakarta, southeast on the road past Bogor toward Bandung. John’s boss, Political Counselor John Henderson, and his wife, Hester, had invited us for our first weekend to go there with them.

On the drive up through lush tropical and semitropical scenery, the first stretch of green we had seen since arriving at Kemayoran Airport, John Henderson explained that their weekend house was on a few acres belonging to the representative of the American motion picture industry, Billy Palmer. Billy was an old Southeast Asia hand, he added, and was said to have grown up at the palace of the Thai king. Billy had had a “good war” during World War II in Southeast Asia working for one of the clandestine services.

From the front porch of the Hendersons’ mountain bungalow, our hosts pointed out to us Billy’s swimming pool, Ambassador and Mrs. Jones’s cottage down the hill, and the low green bushes of the surrounding tea plantation. The horizon consisted of tall, blue, cone-shaped volcanic mountains. In the valley just below, among patchwork squares colored rich gold, brilliant green, and silver, barefoot farmers were guiding big, gray, docile water buffalo to plow terraced fields for another rice crop.

American and European diplomats and businesspeople and their families were sitting or standing around Billy’s swimming pool. The adults mostly were red-faced, slightly overweight, dressed in faded cotton shirts and shorts or sagging bathing suits. (Elastic was usually the first casualty from the effects of scrubbing laundry on rocks or wooden washboards.)

Sprinkled through the crowd around the pool were honey-colored, crisply uniformed Indonesian Army officers in sunglasses, and their elegantly saronged wives, whose thick blue-black hair was caught up in elaborate chignons.

It seemed like one big house party, with swimming, drinking, card playing, and gossiping. This hum of conversation was punctuated occasionally by the sound of a J. Arthur Rank–style gong at one end of the pool, being struck by a manservant in a batik sarong draped below a white drill fitted jacket, to announce meals. Cut off from the heat and squalor of the plains where Jakarta was, this mountain resort seemed to me more like Shangri-La than like a real place in a real country.

At night after dinner, a movie screen was set out on the grass in front of a roofed terrace. Billy’s dozens of guests sat on the terrace to watch the latest film from Hollywood or a cinema classic. Villagers from miles around watched from mats spread out on the grass. Peddlers selling refreshments and curios set up their portable stalls and stoves in front of the terrace and did a lively trade on all sides.

John had once said to me that Asia grows magical after dark—and that was certainly the case here. It was a clear night, and the moon and stars seemed so much closer, with no city lights to dim their brightness. There were also little scraps of light scattered through the grass, from charcoal grills, oil lamps, and anti-mosquito coils. Zippo lighters passed hand to hand as people lighted their cigarettes before the movie began.

It was a classic film: Sergeant York (1941) with a young and handsome Gary Cooper in the leading role of a good country boy who did not like violence but became the most decorated American soldier of World War I. It was based on a true story, and it was easy for us Americans there to feel proud of a country that could produce such a man. I sensed that Billy Palmer’s handpicked Indonesian military guests could share our feelings. The social atmosphere here among these high-level Indonesians made me hopeful that John and I would find Indonesian friends, despite the ugly posters and graffiti that had greeted us in Jakarta. None of us Americans knew then that these pro-Western military men would a few years later save their country, the most populous Muslim country in the world, from falling into the hands of supporters of Mao’s Chinese Communist Party.

We were told that the Palmer estate and the tea plantation around it were surrounded by territory riddled with Darul Islam (Islamic extremist) rebels who were engaged in episodic armed combat against the religiously tolerant central government. The Darul Islam held sway after dark on the mountain road connecting Billy’s estate and Jakarta to the north and Bandung to the south. A couple of years earlier, John Henderson told us, one of his best journalist friends and another American he was traveling with had been flagged down and killed by the Darul Islam on that West Java road. Outsiders like us had no way of telling who was Darul Islam and who was not.

The word was out, however, that Billy Palmer had made a deal with the rebels that they could attend the film showings so long as they maintained a truce while on his property. Billy, who seemed to be the consummate insider, was widely rumored to be the CIA’s chief agent in Indonesia (though I doubt this was the case). But he had clearly learned from his days in World War II special operations how to build up trust and fruitful relations with all sorts of people.

John was invited after the movie to play poker with the big boys—the deputy chief of mission and John Henderson, among others—in Billy Palmer’s bungalow. I waited for him before going to bed, and overheard bits of the conversations around me—some of it apparently in Dutch—among the elegant Indonesian women guests whose high bosoms were visible through their tight-fitting sheer blouses above waistlines that Scarlett O’Hara would have envied. Most of the Western women had already retired for the night.

Sitting there in a bamboo lounge chair and looking up at a blanket of stars, I could hardly believe I was in such an exotic place among such exotic people. I thought if I dozed off and woke up, I might find myself back in Kansas, like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. When John turned up and we went off to our neat, sparsely furnished little bedroom, I told him I was glad we had started off our Foreign Service life in Indonesia. No place else could be so foreign and such a mixture of the wonderful and the terrible.

In the morning, Hester Henderson took me to pay my first protocol call, on Mary Lou Jones, the ambassador’s wife. A tall, rangy woman who looked to be in her late fifties, Mrs. Jones wore a faded cotton dress and no makeup. She was down to earth in her manner, despite her husband’s rank as head of our diplomatic community. The Joneses were now on their second tour in Indonesia and must have had many stories to tell, but I could sense that Mrs. Jones, although courteous to me, was a very private person who would have preferred her weekends to be a respite from protocol.

My call on Mrs. Jones approached its conclusion, and Hester, who had kept the conversation going, rifled through my calling cards and pointed out that I should give Mrs. Jones two of John’s cards and one of mine or, alternatively, I could give her one Mr. and Mrs. card and an extra one of John’s. That was because I was supposed to leave John’s cards on both the husband and wife, since men could call on both men and women, but women were only supposed to call on women. In fact, as was usual during formal calls, neither of the men was present. Odder still, according to Hester, if Mrs. Jones had not been home, I should have turned down a corner of one of the cards and maybe written a note on it—in pencil, not ink. That was because, back in the days when the rules were made, there were no portable pens and thus a pencil showed you had come yourself.

It is easy to laugh at the absurdity of this kind of paying formal calls, but it helped us women feel that we were part of our country’s representation abroad. Since the other diplomats’ wives, regardless of nationality, were operating from the same set of archaic rules, it gave us all a quick and fairly efficient way to meet the other diplomatic families in our own and other embassies. In a secretive dictatorship like Indonesia, our diplomats could sometimes learn what was happening within Sukarno’s inner circle from foreign diplomatic colleagues.

When we got back to Jakarta at the end of the weekend, I was no longer in Shangri-La, but back in Jane Austen country. I spent most mornings of my first month in Jakarta—wearing a dress or skirt and blouse, plus a hat, nylons, and short white cotton gloves and armed with the right calling cards—calling upon the other twenty-eight (yes, twenty-eight) wives of John’s more senior embassy colleagues. Some of these women seemed worth knowing better, and many of their houses were handsome and well arranged, perhaps because these women had more experience of furnishing houses in the tropics than I did. Indeed, they had more experience, period.

Some of these women, however, had become visibly fed up with a life that—in the Jakarta diplomatic setting—made it nearly impossible to exercise their skills, whether professional work of some kind or even cooking and childcare, which were done chiefly by servants.

In those days, wives of American diplomats were often commandeered for various unpaid jobs by the embassy. There was even space in our husbands’ annual performance evaluations for their supervisor to comment on how well the wife entertained and in other ways contributed positively to the mission’s goals. (Nowadays, many more Foreign Service officers are women, and many more wives are either officers themselves or able to work in the local economy, thanks to the tireless efforts of the State Department to obtain reciprocity on work permits for diplomatic spouses abroad.)

. . .

John would chat with these world-weary women on the cocktail circuit. Remembering how at seventeen he had welcomed the National Guard call-up that let him escape from a home then dominated by his mother’s drinking, he seemed to understand where these women’s low spirits were coming from. He would later occasionally say to me of some woman he met who seemed to have once had a spark that “she had died in the war.” I sometimes wondered if that would be my fate, too, after the novelty of being a diplomat’s wife wore off.

American diplomats’ wives are no longer obliged to pay calls or to participate in any way in their husband’s social duties. But in quite a few countries they still have no right to a work permit and can only hope to occupy themselves in volunteer work, social clubs, a job at the American embassy, or perhaps in an American-funded school or business. Given the current climate of opinion regarding women’s roles, no boss’s wife would dare to try to teach subordinate spouses what is expected of them, the way Hester taught me. Yet the wives are still expected to know.

I found calls on foreigners more interesting than calls on other Americans, but they were more complicated, as often the person I called on and I had no more than a few words in a common language. But one Pakistani wife who spoke fluent English was especially cordial to me, expressing gratitude for the American diplomats at her husband’s last post, in Saudi Arabia, where the only chance she had to leave the house and be out of doors unveiled had been when invited to picnics by her husband’s American colleagues. Muslim she might be, but Pakistan in her day was a place (like Indonesia) where an educated Muslim woman enjoyed much more freedom than in the Arab world.

Most of my diplomatic calls were pretty tame affairs. Coffee or tea or orange squash was served, along with something to nibble on, a brief polite conversation took place, and I was expected to leave within the half hour. But not all calls were like that. It is not really stretching a point to say that Barbara Benson’s call on the wife of one of her husband’s Indonesian contacts changed the course of history between our two countries.

Barbara was the wife of Assistant Military Attaché Major George Benson, and was a registered nurse. And when she paid a call on the wife of a highly placed army colonel named Yani, who lived a short walk from the Bensons’ house, she found Mrs. Yani writhing with labor pains; Barbara stayed and helped the midwife deliver the baby.

From then on, the Bensons and the Yanis were closer than family, and the Bensons’ adventurous four-year-old son, Dukie, would sometimes escape his out-of-breath baby amah to wander over to the Yanis’ front porch. Dukie’s father, George, perhaps the most charming Irish American Jakarta had ever known, would routinely walk over to reclaim his son after he came home from work. One evening he found not only Dukie but much of the top brass of the Indonesian army sitting around Yani’s table in front of maps of a part of Sumatra that contained a rebel stronghold. George Benson, having been well trained at West Point, and recognizing the people sitting around the table, immediately understood what was going on. And he could not keep from pointing out to Yani and his colleagues a better way to invade Sumatra and defeat the rebels. They took his advice and it worked, thereby further cementing his good relations with the anticommunist Indonesian Army leadership. (Benson would be called back again and again in future years to work at our Jakarta embassy when someone was needed who knew everyone that mattered.)

The irony was that Benson was not privy to the then closely held secret that the CIA under its director Allen Dulles, abetted by Dulles’s brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and with the approval of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, was supporting the Sumatran rebels and other rebels in Indonesian islands northeast of Java. The Dulles brothers encouraged the rebels and armed them with cash, weapons, logistics, and mercenaries, in the hopes of toppling what they believed to be the dangerously pro-communist Sukarno regime.

A fairly typical Cold War gambit for that era, this covert effort at subverting a country with which we were in theory enjoying friendly relations was so clumsy and inept that the Indonesian government easily uncovered it. Had it not been for the help provided by Major Benson and the near infinite patience and tact of our ambassador to Indonesia Howard P. Jones (who was also at least partly out of the Dulles loop), it is probable that Sukarno would have publicly exposed the plot and used it as a pretext to sever relations with the West and move his country firmly into the Eastern bloc.1

The lesson I drew from that incident was that there are times—fortunately rare—when diplomats on the ground have both the obligation and capability to save our country from the consequences of mistakes made by our bosses at home.

Though I never paid a call that turned out to be half as momentous as Barbara Benson’s, I found there were occasional glamorous moments in diplomacy, such as the annual Queen’s Birthday Ball held (where else?) at the British Cricket Club, better known as “the Box.” While our furniture was in storage in America, I had had shipped out with our most essential belongings my only ball gown. This was a white lace confection made by Worth of Paris—straight out of an Edith Wharton novel. John had insisted we buy it at Bonwit’s in Boston in a wildly extravagant moment, for me to wear to the Harvard senior prom. I had no idea, then, how much use I would get out of such a ball gown over the years.

At the ball a Viennese waltz was played, of course. David Goodall, John’s counterpart at the British embassy, stood to help me from my chair onto the dance floor, and said, “I feel I must warn you, I don’t reverse!” A happy but very dizzy young woman in white lace was returned to her seat afterward, to drink champagne and to feel that the diplomatic life was, every once in a while, precisely what one imagined it should be. David, almost intimidatingly well educated, remained one of our closest friends ever after. He became a consummate British diplomat, and over the years that brought him ever better jobs and higher honors, we stayed in touch. During those years, David taught John and me a lot about what good diplomats do and, also, how differently our closest allies can sometimes approach the same issues our government faces.

I learned another, more painful lesson about dealing with British diplomats during that first year in Jakarta. Through David Goodall, John and I met an absolutely charming and original poet and British council member named Henry, who came from a very modest family background and whose excellent education had been entirely the product of his good brain and hard work. Also through David, we were later introduced to a new, very upper-class British couple at his embassy, whom I shall call Hermione and Alec. Just for fun, we invited Hermione and Alec to our house for dinner, the only other guest being Henry. While we watched helplessly, the couple put Henry through a thorough examination of his background: where had he gone to school? Oxford, ah yes, but they meant school, and Henry was obliged to name the state-financed grammar school he had attended, not a famous so-called public school like Eton or Harrow. And who were his friends? Alec and Hermione didn’t know them. And where did his parents live? And on and on, while John and I cringed with embarrassment at having exposed poor Henry to this onslaught—to which I must confess Henry seemed more inured than John or I were.

The worst came when Henry got to ask them where their parents lived. At the mention of a village somewhere near Bath, Henry said with a twinkle in his eye, “Ah yes, I rather think my father passed through there during the Jarrow Hunger March of ’36.”

I still shudder when I think of that evening. The lesson I drew was never to invite British people to the same small occasion unless I was sure they were from the same class. It would take me longer to learn (from my Congolese giant friend) that I needed to compose every dinner party carefully to make sure all our guests would be comfortable with one another.

I was almost finished with my protocol calls when Hester Henderson, her heart in the right place, over dinner with her husband and John and me, tried to involve me in a Women’s International Club sewing circle. The ladies’ project, she explained, was to make stuffed animals out of cotton felt, as toys for Indonesian children. My own view (which even I knew enough to keep to myself) was that the children would probably prefer a new white blouse or shirt for school. In any case, the prospect of my spending hours each week, sitting around with the club’s ladies sewing, filled me with dread. John, seeing my face, said bravely: “You know, Hester, some people don’t drink and some don’t smoke—and my wife doesn’t sew.” I would have married him again for that alone.

Undaunted, Hester next inveigled me into becoming the treasurer of the Women’s International Club, but I couldn’t get into the club’s postal bank account without bribing the clerk—which John wisely discouraged me from attempting, so I had to resign. Eventually Hester found for me a class of Indonesian women who spoke English and were looking for a native English speaker to help them learn how to give public speeches, since they were seeking to participate in international conferences. Teaching that weekly class of a dozen enterprising women soon became my favorite activity.

Looking back on my introduction to being a diplomat’s wife, I am struck by the almost infinite effort made by the wife of my husband’s boss to help me fit in and find satisfying ways to occupy my time. In those days in our Foreign Service, the boss’s wife was often regarded as a dragon needing to be placated for fear she might breathe fire and destroy one’s husband’s career. Hester probably was a dragon in the sense that she wanted me to learn to do things “the right way,” but I thank her for taking the trouble to teach me what I needed to know.

Note

1. For more about this failed attempt at regime change, read Subversion as Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia, by Indonesia scholars Audrey Kahin and George McT. Kahin, published by New Press in 1995 and based on declassified official US government sources.