Читать книгу By Heart - Judith Tannenbaum - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Mirrors

IN MY FAMILY, September was apples and honey, the start of the new year. Rosh Hashanah, followed ten days later by Yom Kippur. Holy days which I remember mostly as walking the blocks from my grandparents’ house to the synagogue on Fairfax. Los Angeles was hot, red at the edges, windy and dry. I walked home with my mother and aunts. The men were still davening at shul; the women left early to get food onto the table by sundown. My aunts talked: Aunt Nora was learning to drive, there would soon be a sale at Bullocks. The sound of their words was one song, the crunch of fallen sycamore leaves under my shoes was another.

Around the mahogany table, in the evening, sat my bubbe and zadie; my mother; my great-aunts, Ida, Riva and Sadie; aunts, uncles, and cousins from all over L.A. My father. The babies—my sister, Debbie, and cousin, Beth—sat in high chairs. Even without the family in St. Louis and Detroit, every leaf was added to the dining room table. Uncle Aaron, stuck at this table’s foot, sat almost into the hallway. Abie, Izzie, Moishe, Zelig, Icki, ′Fraim. Aunty Emma was the oldest of my mother’s siblings, and when they were children in Detroit, she rounded them up at supper time by singing their names.

The first September I remember is before these Septembers. September 1949, and I’m not at my grandparents’, but five houses north, 1322 Ridgley Drive, the house my father, mother, and I are about to move into. What I see when I remember is my father dismantling a crib in the corner of a small bedroom and light pouring through two south-facing windows. September light, red and gold, low light that steeps more than blazes. My father is bent to his task and he’s talking to me. I don’t remember his words but know he’s telling me that the baby my mother has been carrying was born dead; he’s telling me there is no more baby.

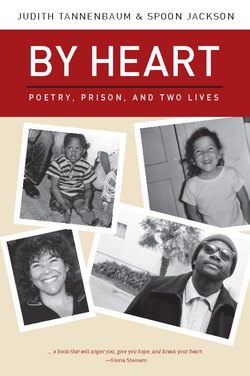

Judith (age four, leaning on table) with her grandparents,Aunt Nora, and a few of her cousins.

FAMILY ALBUM

I remember a whoosh, almost like the light from the windows entering my body. A whoosh that fills me or wakes me or somehow lets me know I have skin and that this skin contains me. I—the one everyone calls Judy—is suddenly on one side of this skin and everything on the other side is not me, not Judy. I must not have known this before, though I don’t remember what I did know. Before, was Judy not distinct from wallpaper, wood floor, double-hung windows, Daddy Bob, kewpie doll, Bubbe? I don’t know, but with that whoosh I was separate. My father was across the room, the closet door was behind me, a tall tree stood outside the west window, and my brother was dead.

My mother came home from the hospital, we moved into our new house, my father was gone all day teaching. And? And where was this baby, this brother? No one mentioned him to me again. I felt restless, so suddenly a self, so suddenly separate. Something hovered. Light? A whisper? My father’s words still in the bedroom? My brother? Wasn’t any adult going to provide that barely-born spirit a place he could settle? Apparently not.

So I did. I scooped my brother into my heart and made him a home.

I don’t remember my brother inside me, don’t remember if his presence was a weight or more like a tickle. Did we speak? Was I sad, or did his presence make me feel less alone? Was he the one I would soon call Stony. Don’t sit down! Stony’s right there on the couch. Or: Wait. Stony’s still climbing the stairs. Did my dead brother’s spirit shape itself into Stony, the being others labeled “Judy’s imaginary friend”?

I lay awake most nights in that small bedroom where my father had dismantled the crib, too frightened to close my eyes. There were monsters in the closet, that was for sure. The searchlight whose source my father explained so precisely was really, I knew, no matter my father’s logic, a trail for witches. I could hear them cackle and call. Monsters, witches, and bombs likely to fall on the roof of our house. La la la la I tried to sing to myself in a you-can’t-get-me pretend bravado. Or I told myself stories: I was the Lone Ranger’s girlfriend; I played Sparky’s magic piano as in the new record my mother had recently bought me. Conjure the sound of the Lone Ranger’s boots on gravel,I didn’t tell myself but must have somehow enjoined. Conjure Sparky’s red hair, hair like Cliffy’s, our carrot-topped neighbor. Imagine yourself into a whole other world and maybe you will be safe.

Fear lived in my legs, my feet, in the big brown shoes I wore that covered even my ankles. Fear in the trouble my feet had simply resting on ground. Fear lived in the device the doctor gave my mother to correct my turned-in hips. I placed my feet in this contraption at night, then lay on my back unable to move. I was a good girl—everyone said so—reasonable, so the panicked scream ready to burst buried itself instead in my throat.

My own favorite made-up story had me lost in a forest. I was cold, so cold. I threw off my actual blanket—thin, white cotton, flowers in quilted squares, bordered with brown scallops—to make nearly real the arctic I summoned. I imagined a bleak, stormy wind. I’d been lost for days. No food. Probably rain. When I was so cold I couldn’t get any colder, I heard a sound in the stillness. Footsteps on leaves. A stranger appeared. He wrapped me in blankets and walked with my body held in his arms. I shivered, but he kept on in the dark. I imagined each moment of our walk for as long as I could, drawing it out. I felt so safe against this big body. Eventually we wound up inside a hut that was warmed by a fire. Somewhere I’d never been before. The stranger called the place home.

I told myself stories and taught myself to read stories in books, like the Golden Book I was allowed to buy each week at the supermarket as my parents shopped for groceries: Pantaloon, Nurse Nancy, Doctor Dan the Bandage Man. My mother read me longer stories in installments—B is for Betsy, The Wizard of Oz, K’tonton.

My father told stories from the floor where he lay prone between Debbie’s bed and my own. Daddy Bob had three on-going series. Hal Stories featured a young, studious boy, a good boy, as my father was himself told always to be. Zillie was a pluckier hero, a courageous girl who, with a pinch of salt, became invisible and, with the tiniest taste of sugar, could fly.

The series I loved most was the one my father called Bob and Emma Stories. These were about my father’s childhood first in Cripple Creek, Colorado, and then in Santa Ana, California. Emma, his older sister, got marquee billing, but most of the stories were about Bob, or Robert as he was called as a child.

For example: Five year old Robert begged and begged his mother for a donkey. Grandma Nettie resisted; Robert persisted. Finally his mother borrowed a neighbor’s donkey for an afternoon and Robert was joyous. But no sooner had the boy been lifted onto the animal’s back than the donkey bucked. My father tumbled, hit his head on a rock. Grandma Nettie wrung her hands, I knew it. I knew this would happen, I knew it.

Or: Mr. Dewar owned the general store in Cripple Creek, and he taught young Robert to sing “Just a Wee Doch an Dorus” as the Scotsman Harry Lauder sung the song. Mr. Dewar offered Robert a deal. Sing the song for customers and earn a handful of cookies.

Sometimes my father paused in his telling. The pause lengthened, grew into silence, and finally we heard a slight snore. Debbie and I rolled to our sides, looked down from our beds, and found our father asleep on the floor. Other times the telephone rang in the kitchen, and my mother came to our bedroom door to announce a colleague or student from UCLA on the line. My father most often took the call, and Debbie and I were left with a half-told story, having to find our own way toward sleep.

Aunty Riva also told stories. When she was a young girl in Russia, she came down with bronchitis every winter. Her father saved money and the year she turned sixteen, he planned to send her to the Riviera through the cold season. The doctor shook his head. This girl won’t live another winter, why bother with her? Aunty Riva laughed when she told that story, for here she was, in her late sixties, a survivor of dozens of winters. A survivor of worse.

Judith (age seven) with sister Debbie

FAMILY ALBUM

Aunty Riva told stories of escaping Russia just after the revolution; of tutoring the niece and nephew of the grand duke of Finland; of years in the ex-pat community in Berlin; of putting an ad in the Jewish Daily Forward trying to locate my grandmother in America; of making it to this country at the last possible minute, barely escaping Hitler. In Los Angeles, Aunty Riva, delicate and speaking perfect French, transformed herself from Riva Velinsky into Vera Villard. Madame Villard taught French to Beverly Hills matrons; Madame Villard was governess to Judy McHugh, Eddie Cantor’s granddaughter.

When she visited from Detroit, Aunty Emma also told stories. She was the only one of my grandparents’ children born in Russia, and she arrived on the boat with my bubbe in 1907. That boat landed in Boston on the fourth of July. When my grandmother saw the firecrackers exploding, she cried out—my Aunty Emma reported—“They have pogroms in America, too?”

My world was my mother’s family, and the Lazaroffs didn’t need to tell every story out loud to convey what they wanted to teach me. For there I was, kneeling on the kitchen chair, rolling dough into plump cylinders along with Bubbe as we baked coffee cake in her kitchen. There I was, staring at the photo in my grandparents’ bedroom of Aunty Emma in her UNRA uniform on her way to the Displaced Persons camps after World War II to sing “Ani Mamin” to the survivors.

On Purim, Bubbe assembled baskets of fruit and baked goods and handed them to me. Shalach Manos, Bubbe said, and not much else. She never used the word “poor,” or explained the requirement to help those in need. Bubbe just took my hand as we delivered one basket to the old woman on the second floor in the back of the apartment house two doors down and another to the recently widowed mother around the corner on Packard. I don’t remember her words, but somehow Bubbe let me know being poor was not a fault, and that the Purim gift was ours—hers and mine. I was shy and afraid, knocking on the doors of people I didn’t know, but I also felt something like pleasure or pride, as though my bubbehad chosen me to help right the scales of justice.

If some barking dog chased me as I walked up Ridgley Drive on my way home from school, if some neighborhood boys teased me about a bomb about to fall only on my side of the street, there was my grandparents’ front door—five houses closer than my own—on which I could knock. I knew that front door would open and whoever stood there would welcome me in. Bubbe would say something in Yiddish to Zadie, and though he would sigh, he’d put on his jacket, take my hand, and walk me the rest of the way home.

My father’s family—the Tannenbaums and Porgeses—lived nowhere near Ridgley Drive. Daddy Bob’s parents, Henry and Nettie, died before I was born; my great-aunts lived in Denver. When a young woman, Aunt Irene taught in small Rocky Mountain towns. She boarded with a student’s family, she told us, and rode to school side-saddle. Though Jewish, too, there was no Judeleh out of her mouth, no shaine maidel. Aunt Irene addressed each one of us as “dearie.”

My father’s sister Emma—I called her Ahmee—lived with her family in Glendale. The Elconins seemed exotic, Glendale not Jewish at all. Brock-mont Drive, a winding road that climbed along a steep hillside, looked nothing like my neighborhood of square streets: Hauser, Curson, Spaulding. No sidewalks in Glendale. No Pico, the big boulevard at the end of my block, crowded with shops. Where were the delis like Joe and Ann’s, the kosher butchers, banks, and beauty shops? Where was the five-and-dime filled with comic books and cherry phosphates?

Often we four Tannenbaums met the Elconins at El Cholo on Western. Enchiladas, not brisket. Tortillas, not chicken soup.

“Who was Jesus?” I asked.

“A man. A very good man,” my mother responded.

“Oh little town of Bethlehem,” I sang after learning the carol in school.

“A beautiful song,” said my mother. “But maybe don’t sing it for Zadie.”

A story my father didn’t tell us until we were older was the one in which he was chased up a tree by Santa Ana school kids yelling “Jew Boy” and “kike.” Grandpa Henry came out of the house for the sake of his son, but the man was no match for the taunting children. My Lazaroff uncles walked the streets of Detroit ready to use their fists if need be, but my father’s solution to ugly hurled words was to become the smartest, the best, the top of his class. In a letter he wasn’t meant to see, a junior college professor wrote a glowing recommendation to the admissions department at the University of Chicago: Robert isn’t like the rest of his tribe.

“Well, I’ll be an African Gazoop,” my father said when surprised by some news. Imagined animals with strange made-up names, puns, and jokes: my father liked being funny. He chomped down on a pretend cigar and wiggled his eyebrows, playing Groucho Marx at my seventh birthday party. “Say the secret word and win a hundred dollars,” Daddy Bob imitated Groucho’s Brooklyn accent.

Many bedtimes, my mother sang Ai loo loo loo or lullaby and goodnight, with roses bedight. The song I loved most, though, was neither Yiddish scat nor Brahms. I’ve got shoes, you’ve got shoes, all God’s children got shoes. I tried to parse the meaning of Everybody talkin’ ′bout heaven ain’t goin’ there, understanding that not everybody talkin’ was goin’, but not about irony and the frequent disconnect between words and action.

I wanted to trust that people meant what they said. So when, for example, Bubbe and I were at Aunt Annette’s and my cousin Beryl pointed to the clock as we readied to leave and whispered, “Prisoners escape at 5:00 every evening. They gather in the tunnel under Pico. You’d better hurry,” I believed her. I urged Bubbe to walk faster so we could make it through the pedestrian tunnel before the prisoners arrived. I even told her the reason. But Bubbe just smiled and continued her slow pace. I respected Bubbe. But my grandmother wasn’t from this country and I figured Beryl probably knew more about prisoners and tunnels than did Bubbe.

Beryl again. We sat side by side in the breakfast nook at my house, and Beryl—five years my senior—took on the big-sister task of getting me, the pickiest of eaters, to finish my lunch. She used logic, warnings, and threats. And then I heard a rhythmic pounding from under the table. I could see Beryl’s thighs rise and fall. Even so, when she said, “The sheriff is coming, the sheriff is coming. Can’t you hear his horse getting close? Better eat all your food fast or the sheriff will get you,” I believed her.

Why would Beryl lie? Why would anyone lie?

As much as I wanted to trust, I often sensed a chasm between sincere explanation and some truth I couldn’t see but did perceive. My fears lived in this gap. When my father explained about that machine many blocks south whose light swept the sky through my bedroom window, I knew he was telling the truth. But I knew, too, that the searchlight was a path witches traveled to reach me. When my mother told me that the neighborhood boys were teasing about a bomb falling on our house and no other, I understood what she said, but the boys were insistent, and who could be sure a bomb wouldn’t choose the home of the family whose name ended in baum?

I spent a great deal of time scanning the terrain between what appeared on the surface and what lurked underneath. The surface: my family, our clean kitchen, the smell of coffee cake baking, “Your Show of Shows” Saturday nights on TV. Underneath: witches, bombs, the buzzing fear in my skull.

How much of those years was spent inside on couches or chairs! Those inside spaces were actual rooms that I walked through, and they also occupied my imagination. The Aunties’ apartment—with its interior staircase, its covered porch over the street—provided the layout I most often summon when an apartment appears in a novel I’m reading. Fifty-five years later and I still catch the smells of that second-floor flat: apple kuchen, strudel, and old lady musk.

If a novel takes place in a house, I usually imagine our own home on Ridgley Drive. Whether the text describes one or not, I see a big front porch above a wide lawn that is edged by beds of pansies and stock. I see our entry hall with its love seat and the breakfast nook in our east-facing kitchen. My friend Lolly’s apartment gave me the set for any story taking place in a railroad flat. If a dwelling is described as “art deco,” the kitchen in Rosalind’s apartment appears in my mind. A novel placed in the suburbs summons Uncle Aaron’s house in the Valley. Sometimes the fish tank from Uncle Al’s house on Citrus sneaks in, or the maple table in Aunt Nora’s kitchen, or Bubbe’s O’Keefe and Merritt stove, the place mats and tall tumblers at my friend Mary Jo’s, the tiny cubes of ice cream Ahmee served for dessert.

I wasn’t always inside, though. I climbed trees with Cliffy and Stanley, the twins next door, and played statues with Mary Jo on our lawn. I walked to the bus stop on Pico to meet Zadie, shopped for my mother at Joe and Ann’s, and sat under the fig tree in my grandparents’ yard making purses from the thick fallen leaves. I helped Zadie carry the trash to the incinerator out back and watched him fill the stone cave, set the fire, close the latch. Some Sundays, Daddy Bob took me to Beverly Land where I rode the horse named Patches. I loved the two trees that stood at the furthest edge of our back garden. Twinkle Twinkle, I named one; Lullaby and Good Night was the other.

Inside was best, though, sitting on the wooden bench of our breakfast nook dictating stories that my mother transcribed. At school, too, I liked most the big crayons and the large sheets of newsprint. Reading circle didn’t make me nervous, and I didn’t mind being quiet and paying attention when the teacher told us what to do. Outside was where kids taunted Tannenbaum Atom Bomb Cannonbomb and where I stood as far back as I could watching others play jacks and jump rope. Outside was trying to make myself invisible when partners were picked and teams chosen.

Anyway, I liked listening and staying quiet: teachers, parents, uncles, and aunts. I liked watching the adults at home gesture as they talked about Edward R. Murrow, loyalty oaths, McCarthy, and Stevenson. I loved listening to the music made by their voices and watching emotion play on the planes of their faces. Lazaroffs, Tannenbaums, Porgeses: As though I were in a ballroom whose walls were mirrors shining light in all directions. It wasn’t me reflected, exactly, but some bright beauty, a multi-faceted flashing. Years later, when I heard Sweet Honey in the Rock sing Ysaye Barnwell’s “There Were No Mirrors in My Nana’s House” with its repeating line, and the beauty that I saw in everything/was in her eyes, I recalled my own family.

When, as a young mother volunteering in my daughter’s kindergarten class, I began sharing poems in schools, I found that teaching allowed my eyes to mirror love, too. Not only to Sara, my daughter, but to children I didn’t even know. By September 1986, when Spoon and I sat in one of San Quentin’s basement classrooms talking about poems, this being-a-mirror had become a favorite aspect of teaching: reflecting to others their own joy, beauty, curiosity, excitement, and humor.

San Quentin and beauty, prison and joy. I’d only taught the class in which I’d met Spoon for a single year, but that was more than enough time to note the oddity of teaching poetry—with poetry’s inherent invitation to open one’s mind, heart, spirit, and senses—in the closed world of a maximum security prison. Sure, there were some guards who joked in a friendly fashion with the men in blue and a few administrators who spoke about inmates as human beings, but the institution—the five tiers of cells in each cellblock; the locks, keys, and cages; the rules and procedures—seemed designed to reflect one consistent image of people in prison: monsters capable only of evil.

But my students weren’t monsters. Despite the fact that almost all of them had been convicted of murder, they weren’t evil. They weren’t ciphers, either—not generic “convicts” or “inmates.” Angel, Coties, Elmo, Gabriel, Glenn, Richard, Smokey, Spoon—each man had a name, each was a human being with his own nature and experience.

Angel told us that his father was a newspaperman in the Chicano community around Bakersfield. Quick and wiry, Angel warned us about manipulation and an elite based on “material, power, and possession,” a phrase he sputtered at least once each class session. My favorite of Angel’s poems demanded, “Who decides what a poem is?” letting us know “I am a poem/The world is a poem/The butterfly is a poem…/This poem is a poem/Speaking in tongues is a poem/A rock is a poem/Shit is a poem/And the corn in it too/is a poem.”

Coties talked a lot about his children. He wrote them letters and called, but his family rarely had money for the long trip from Los Angeles so he did what he could at a distance to be the good father he wanted to be. Coties worried, not only about his own son and daughter, but about the community so many children like his own were growing up in. How had drugs become more important than black pride, Coties wondered. Coties let me know about anyone mentioned in the news doing good work, especially with youth. He told me to send these men and women poems from San Quentin; he told me to invite them all in to visit.

Elmo was the man guest artists commented on first as we walked away from the classroom, out the three gates, and down the long pathway back to our cars. “How can someone that smart be in prison?” most wondered. Elmo was not only smart, he could also talk with anyone, whether a fish (someone brand new to the prison), a professor, or a visiting poet. Elmo grew up black in a beach town north of Los Angeles, where he’d counted as friends thugs, hippies, low riders, and spiritual seekers. Elmo was editor of The San Quentin News, and both my strongest ally and biggest challenge. My ally because he went out of his way to teach me what he thought I needed to know about prison and because I could tell he looked out for me, even though I didn’t really understand what such looking out involved. And my challenge because Elmo’s sharp mind homed in on whatever seemed like a cover-up. Since childhood, I’d heard in my head what I called The Voice—a male drone that noted my every weakness, sloppily worded speech, or mixed motivation. Elmo noticed too, and always spoke out. I cared what Elmo thought and often over-reacted because his voice sounded so much like that of The Voice.

The mirrors of our classroom were poems read and written, visiting guest artists, conversations, laughter, and the human relationships we were building between us. In these mirrors Angel, Coties, Elmo, Spoon, and the others were not only prisoners, but also poets; not animals capable only of one worst act, but kind, funny, smart, generous, often sweet men. In San Quentin’s world of concrete and hatred, our classroom was allowed to reflect light. I loved being in that room.