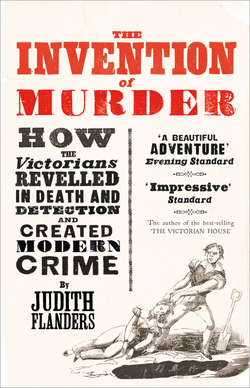

Читать книгу The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime - Judith Flanders - Страница 11

FOUR Policing Murder

ОглавлениеOne man, perhaps, can be credited with the creation of Scotland Yard, although he did not live to see it, and would not have enjoyed it if he had. That man was Daniel Good, and he was not a policeman or a politician, but a murderer; not the hunter, but the hunted.

Until 1842, the police saw themselves primarily as performing the function Parliament had established them for: prevention of crime. It was hoped by Peel and his supporters that this emphasis would encourage an initially reluctant populace to view the new police as protectors of the weak and the oppressed, instead of a tool of the powerful. Up to a point, this had happened. Even with the Cold Bath Field riot a vivid memory, police crowd-control was quickly discovered to be much more satisfactory than calling out the army – truncheons got the same results, with far less damage, than mounted dragoons with sabres. One of the earliest attempts at crowd-control by the new police was in 1830, three years before Cold Bath Field, when a week of rioting followed the Duke of Wellington’s rejection of parliamentary reform. Seven thousand troops were held at the ready, but were never deployed; instead, 2,000 London policemen marched. The mobs targeted them, shouting ‘Down with the New Police. Down with the Raw Lobsters!’ Handbills were distributed: ‘These damned Police are now to be armed. Englishmen, will you put up with this?’ Yet there were no deaths, nor even any broken bones. ‘A week’s rioting in a city with a population nearing 2 million had for the first time in English history been suppressed. by a. civil force armed only with pieces of wood,’ wrote one modern historian.

There were, however, limitations to this preventative role, and the eruption of Daniel Good into the national consciousness highlighted the one-sided nature of Peel’s force. The police were paid to prevent violent crime. What happened afterwards, if prevention failed?

Daniel Good was a coachman employed by a Mr Quelaz Shiell in the hamlet of Roehampton, south-west of London. He had been keeping company with Jane Jones, a laundress who lived in Manchester Square, who was known as ‘Mrs’ Jones, even though there was no Mr Jones and her eleven-year-old son called Daniel Good ‘Father’. But in 1842 Good met Susan Butcher, and Mrs Jones had come to hear of it. To soothe her, Good invited her out to Roehampton, while the boy was sent overnight to a friend. The next day, Monday, 6 April 1842, Good visited a pawnbroker in Wandsworth, where he bought a pair of black knee breeches. As he was leaving, however, the pawnbroker’s assistant saw him take a second pair of trousers. The pawnbroker went to the police in the Wandsworth, or V, Division to report the matter.

A constable was assigned this case of trouser-theft and two days later, accompanied by two stable boys (Good had a reputation for violence), he went out to talk to Good. He found him in the stables, and in an emollient frame of mind, immediately offering to return to the pawnshop with the constable to pay for the goods. The constable said that was not in his orders; he was there to search for the stolen trousers. He began in the harness room, where, moving a truss of hay, he saw what he thought was a dead goose. At that moment he heard the stable door slam, turned around and found that Good had fled, locking him and his companions inside. The constable now realized that the goose was actually a woman’s torso, without legs, arms or head, ‘the belly. cut open, and the bowels taken out’. He and the stable boys broke down the door, but once free, instead of pursuing Good, who at that point had been gone less than a quarter of an hour, the constable resumed his search of the barn, finding a bloodstained mattress. Only then did he send off for reinforcements, waiting for them at the stable. When they arrived, they too showed little desire for the chase, and instead everyone returned to Wandsworth police station for further orders.

When, nearly two hours later, more senior police arrived, they too thought their first task was to search the stable. Evidence of a horrible crime was readily found: an axe, saw and knife covered with blood, together with a fire that showed signs of having recently burnt fiercely – ‘there were pieces of wood, coal, and straw, a great quantity more than was necessary for any common fire’ – while in the ashes underneath were pieces of bone. Only now was Mrs Jones’s young son questioned, and the police heard that he had been sent away for a night. The gardener’s son added that he had seen Mrs Jones that same day at Roehampton, wearing a blue bonnet.

In the late 1830s Commissioner Richard Mayne had instituted a city-wide system of ‘route-papers’ for the dissemination of police information. Every morning, the superintendent of each division had to write a complete summary of all unsolved crimes that had occurred in his district over the previous twenty-four hours, with full details, including whatever information was available concerning the suspects. A copy of every route-paper was sent daily to all divisions, so that each superintendent had a list of every unsolved crime throughout London, plus information about wanted men, suspects and so on, information which was in turn passed to the constables on the beat.

No route-paper was written on the missing Daniel Good for twenty-four hours. And when it was, there being no overall detective organization, each division that held a piece of the jigsaw started work on its own. Nine divisions followed different leads, with no coordination. Putney police discovered that Good had been seen quarrelling with a woman at the Spotted Horse tavern in Roehampton. Meanwhile in Marylebone, D Division learned that Good had spent the night at Mrs Jones’s lodgings, but by the time they arrived at the house he was long gone, taking with him Mrs Jones’s bed, trunk, a box and a hatbox. The cab driver who had driven him away was identified, and he said he had driven his passenger to Whitcombe Street, near Pall Mall. As this was not in D Division’s area, Marylebone police took no further action. C Division covered Whitcombe Street, and they printed handbills describing Good, and posted placards throughout London and the suburbs detailing the crime and Good’s appearance. Witnesses reported that Good had gone from Whitcombe Street to the Spotted Dog pub in the Strand, before moving on to Spitalfields, in H Division. C Division therefore lost sight of him. It was only on yet another search of the stables that a letter from Mrs Butcher, from an address in Woolwich, was found. V Division forwarded this information to R Division at Greenwich, who questioned Mrs Butcher at her lodgings. On the day the murder was discovered Good had visited her, leaving behind some clothes he said had belonged to his dead wife. The items included a blue silk bonnet and a reticule, both of which had been described by the Manchester Square residents as belonging to Mrs Jones. The bonnet, furthermore, looked very much like the one the gardener’s son had seen Mrs Jones wearing. Good had also told Mrs Butcher about a mangle she might have, although she could not remember precisely where he had said it was. The police may not have been able to find Good, but here was confirmation that they were hunting the right man: the day before the discovery of the body, Good had been giving away Mrs Jones’s possessions. He, at least, appeared to think she would no longer want them. The police offered a £100 reward for information, to which on 12 April, four days after the discovery, the Putney magistrates added another £50.

After the discovery of what was presumed to be Mrs Jones’s body, the coroner for the district had initially requested that it be kept in situ at the stable, for identification purposes – the assumption was that Good would be rapidly captured, and that the inquest jury would visit the scene of the crime. Very shortly, however, her body was instead playing a part in the entertainment world, as it was displayed to the curious. The Times was eloquent on the subject. On 8 April it commended the viewings: ‘very properly’, the police were permitting entry only to ‘the principal inhabitants of the neighbourhood’. Four days later, however, ‘vehicles of every description, from the aristocratic carriage to the costermonger’s cart’ were permitted to enter, and with the arrival of these working-class spectators the display had now become a ‘disgusting exhibition’.