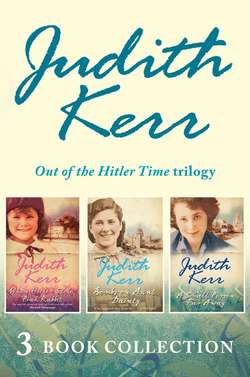

Читать книгу Out of the Hitler Time trilogy: When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, Bombs on Aunt Dainty, A Small Person Far Away - Judith Kerr - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеSuddenly she found herself being gently shaken. She must have been asleep. Mama said, “We’ll be in Stuttgart in a few minutes.”

Anna sleepily put on her coat, and soon she and Max were sitting on the luggage at the entrance of Stuttgart station while Mama went to get a taxi. The rain was still pelting down, drumming on the station roof and falling like a shiny curtain between them and the dark square in front of them. It was cold. At last Mama came back.

“What a place!” she cried. “They’ve got some sort of a strike on – something to do with the elections – and there are no taxis. But you see that blue sign over there?” On the opposite side of the square there was a bluish gleam among the wet. “That’s a hotel,” said Mama. “We’ll just take what we need for the night and make a dash for it.”

With the bulk of the luggage safely deposited they struggled across the ill-lit square. The case Anna was carrying kept banging against her leg and the rain was so heavy that she could hardly see. Once she missed her footing and stepped into a deep puddle so that her feet were soaked. But at last they were in the dry. Mama booked rooms for them and then she and Max had something to eat. Anna was too tired. She went straight to bed and to sleep.

In the morning they got up while it was still dark. “We’ll soon see Papa,” said Anna as they ate their breakfast in the dimly-lit dining room. Nobody else was up yet and the sleepy-eyed waiter seemed to grudge them the stale rolls and coffee which he banged down in front of them. Mama waited until he had gone back into the kitchen. Then she said, “Before we get to Zurich and see Papa we have to cross the frontier between Germany and Switzerland.”

“Do we have to get off the train?” asked Max.

“No,” said Mama. “We just stay in our compartment and then a man will come and look at our passports – just like the ticket inspector. But” – and she looked at both children in turn – “this is very important. When the man comes to look at our passports I want neither of you to say anything. Do you understand? Not a word.”

“Why not?” asked Anna.

“Because otherwise the man will say ‘What a horrible talkative little girl, I think I’ll take away her passport’,” said Max, who was always bad-tempered when he had not had enough sleep.

“Mama!” appealed Anna. “He wouldn’t really – take away our passports, I mean?”

“No …no, I don’t suppose so,” said Mama. “But just in case – Papa’s name is so well known – we don’t want to draw attention to ourselves in any way. So when the man comes – not a word. Remember – not a single, solitary word!”

Anna promised to remember.

The rain had stopped at last and it was quite easy walking back across the square to the station. The sky was just beginning to brighten and now Anna could see that there were election posters everywhere. Two or three people were standing outside a place marked Polling Station, waiting for it to open. She wondered if they were going to vote, and for whom.

The train was almost empty and they had a whole compartment to themselves until a lady with a basket got in at the next station. Anna could hear a sort of shuffling inside the basket – there must be something alive in it. She tried to catch Max’s eye to see if he had heard it too, but he was still feeling cross and was frowning out of the window. Anna began to feel bad-tempered too and to remember that her head ached and that her boots were still wet from last night’s rain.

“When do we get to the frontier?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” said Mama. “Not for a while yet.” Anna noticed that her fingers were squashing the camel’s face again.

“In about an hour, d’you think?” asked Anna.

“You never stop asking questions,” said Max, although it was none of his business. “Why can’t you shut up?”

“Why can’t you?” said Anna. She was bitterly hurt and cast around for something wounding to say. At last she came out with, “I wish I had a sister!”

“I wish I didn’t!” said Max.

“Mama …!” wailed Anna.

“Oh, for goodness’ sake, stop it!” cried Mama. “Haven’t we got enough to worry about?” She was clutching the camel bag and peering into it every so often to see if the passports were still there.

Anna wriggled crossly in her seat. Everybody was horrible. The lady with the basket had produced a large chunk of bread with some ham and was eating it. No one said anything for a long time. Then the train began to slow down.

“Excuse me,” said Mama, “but are we coming to the Swiss frontier?”

The lady with the basket munched and shook her head.

“There, you see!” said Anna to Max. “Mama is asking questions too!”

Max did not even bother to answer but rolled his eyes up to heaven. Anna wanted to kick him, but Mama would have noticed.

The train stopped and started again, stopped and started again. Each time Mama asked if it was the frontier, and each time the lady with the basket shook her head. At last when the train slowed down yet again at the sight of a cluster of buildings, the lady with the basket said, “I dare say we’re coming to it now.”

They waited in silence while the train stood in the station. Anna could hear voices and the doors of other compartments opening and shutting. Then footsteps in the corridor. Then the door of their own compartment slid open and the passport inspector came in. He had a uniform rather like a ticket inspector and a large brown moustache.

He looked at the passport of the lady with the basket, nodded, stamped it with a little rubber stamp, and gave it back to her. Then he turned to Mama. Mama handed him the passports and smiled. But the hand with which she was holding her handbag was squeezing the camel into terrible contortions. The man examined the passports. Then he looked at Mama to see if it was the same face as on the passport photograph, then at Max and then at Anna. Then he got out his rubber stamp. Then he remembered something and looked at the passports again. Then at last he stamped them and gave them back to Mama.

“Pleasant journey,” he said as he opened the door of the compartment.

Nothing had happened. Max had frightened her all for nothing.

“There, you see …!” cried Anna, but Mama gave her such a look that she stopped.

The passport inspector closed the door behind him.

“We are still in Germany,” said Mama.

Anna could feel herself blushing scarlet. Mama put the passports back in the bag. There was silence. Anna could hear whatever it was scuffling in the basket, the lady munching another piece of bread and ham, doors opening and shutting further and further along the train. It seemed to last for ever.

Then the train started, rolling a few hundred yards and stopped again. More opening and shutting of doors, this time more quickly. Voices saying, “Customs …anything to declare …?” A different man came into the compartment. Mama and the lady both said they had nothing to declare and he made a mark with chalk on all their luggage, even on the lady’s basket. Another wait, then a whistle and at last they started again. This time the train gathered speed and went on chugging steadily through the countryside.

After a long time Anna asked, “Are we in Switzerland yet?”

“I think so. I’m not sure,” said Mama.

The lady with the basket stopped chewing. “Oh yes,” she said comfortably, “this is Switzerland. We’re in Switzerland now – this is my country.”

It was marvellous.

“Switzerland!” said Anna. “We’re really in Switzerland!”

“About time too!” said Max and grinned.

Mama put the camel bag down on the seat beside her and smiled and smiled.

“Well!” she said. “Well! We’ll soon be with Papa.”

Anna suddenly felt quite silly and light-headed. She wanted to do or say something extraordinary and exciting but could think of nothing at all – so she turned to the Swiss lady and said, “Excuse me, but what have you got in that basket?”

“That’s my mogger,” said the lady in her soft country voice.

For some reason this was terribly funny. Anna, biting back her laughter, glanced at Max and found that he too was almost in convulsions.

“What’s a …what’s a mogger?” she asked as the lady folded back the lid of the basket, and before anyone could answer there was a screech of “Meeee”, and the head of a scruffy black tomcat appeared out of the opening.

At this Anna and Max could contain themselves no longer. They fell about with laughter.

“He answered you!” gasped Max. “You said, ‘What’s a mogger’ and he said …”

“Meeee!” screamed Anna.

“Children, children!” said Mama, but it was no good – they could not stop laughing. They laughed at everything they saw, all the way to Zurich. Mama apologized to the lady but she said she did not mind – she knew high spirits when she saw them. Any time they looked like flagging Max only had to say, “What’s a mogger?” and Anna cried, “Meeee!” and they were off all over again. They were still laughing on the platform in Zurich when they were looking for Papa.

Anna saw him first. He was standing by a bookstall. His face was white and his eyes were searching the crowds milling around the train.

“Papa!” she shouted. “Papa!”

He turned and saw them. And then Papa, who was always so dignified, who never did anything in a hurry, suddenly ran towards them. He put his arms round Mama and hugged her. Then he hugged Anna and Max. He hugged and hugged them all and would not let them go.

“I couldn’t see you,” said Papa. “I was afraid …”

“I know,” said Mama.