Читать книгу The Hotshot - Jule Mcbride - Страница 8

1

Оглавление“MA WON THE LOTTERY?” Truman Steele was still unable to believe it. The jackpot had been growing for weeks, and because it was June first and another hot, steamy New York summer was right around the corner, people had been amusing themselves by speculating about the lucky winner on subways, street corners, and around office watercoolers. Every day, the TV news depicted long lines outside delis and street kiosks where people waited to buy tickets, and the New York News had been running man-in-the-street interviews, asking people what they’d do if they won the huge windfall.

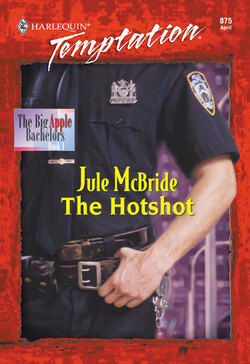

Truman had told himself he’d buy a fishing boat, maybe vacation in Vegas and invest in blue-chip stocks, but now that he might actually get a third of the money, he wasn’t so sure. He needed to rethink his game plan. Wearing the NYPD’s standard-issue navy uniform, he stretched his long legs, then put one hand on his holster and paced to and fro in his oldest sibling’s childhood bedroom. Sullivan’s room was where the three brothers had retreated to mull over family crises since time immemorial.

Not that winning fifteen million dollars was a crisis, exactly. At least not yet, thought Truman, releasing a throaty whistle. “I must have bought thirty tickets.”

“Me, too,” confessed Rex, who’d kicked off dirty sneakers so he could lie on a neatly made twin bed so small it was hard to imagine Sullivan Steele ever occupying it. The only brother to work undercover, Rex was a master of disguises. He’d come from a stakeout looking homeless, sporting a scraggly black beard, baggy, oil-stained jeans and a questionably perfumed trench coat, which he’d thankfully left outside.

“You buy any tickets, Sully?” asked Rex.

Sullivan shook his head. “Waste of money,” said the oldest, thrusting his hands into the pockets of gray suit trousers. “At least I thought so.”

“What were you going to do if you won, Rex?” asked Truman.

Vanish and start a whole new life, thought Rex, picturing himself wearing white, rolled-up trousers while combing a beach for shells. His throat constricted as he glanced away. Unlike his brothers, Rex had never wanted to be a cop, although he rarely admitted it, even to himself. Rex was still haunted by how scared he’d been as a kid every morning when their father holstered his gun and left for work. He’d always waited for the evening Augustus Steele wouldn’t make it home for dinner, and because Rex wouldn’t put another kid through that worry, he’d long ago decided that having a family and working for the NYPD didn’t mix. He finally shrugged. “I don’t know. Fifteen million’s a lot of dough, little brother.”

“Sure is,” agreed Truman, staring through a window into the courtyard, admiring a leafy jungle of trees, bushes and ferns. Before Sheila Steele had been blessed with one of the biggest lottery wins in New York history, she’d also been the more modest recipient of a green thumb and a brownstone. Situated on Bank Street in the West Village, the Steeles’ home had been handed down through Sheila’s family, and because of the expense of maintaining it in Manhattan, the upper two floors were rented to tenants. From the front, despite cheerful green shutters, the place remained somewhat gloomy, a massive stone edifice on a gray street, banked by gray sidewalks and equally gray parking meters. Tourists would never guess at the bright, cozy interior, or the sprawling riot of plants and flowers Sheila kept thriving in the courtyard in back.

“Fifteen million,” Truman said again. “Five each.”

Sully shook his head, the same wary suspicion in his eyes that had made him, at thirty-six, the youngest cop in New York to become captain of a precinct. “If Ma hadn’t shown us the letter from the lottery board, I wouldn’t have believed her.”

Rex chuckled. “Don’t be so suspicious, Sully. This is Ma we’re talking about. Not a criminal.”

“Beg to differ,” countered Truman. “Correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t Ma just say she expects us to find wives? And if we don’t, she’s going to give all that money away to a foundation that saves sea turtles?”

“They also save marine iguanas,” reminded Rex.

“And don’t forget the flightless cormorants,” added Sullivan dryly.

“Oh, right,” whispered Truman. “Flightless cormorants.”

At that, the three brothers simply stared at each other in shock. Rex’s shoulders started shaking with suppressed laughter, then Sullivan gave in, cracking a grin, and then Truman said, “What the hell is a flightless cormorant, anyway?”

“A bird, I think,” said Sully.

But that wasn’t confirmed, since suddenly, none of the men had the breath to talk. Sully gasped, clapping Rex’s shoulder affectionately, and Truman doubled, slapping his knee and laughing until he was wiping tears from his eyes. Each was contemplating the life-altering, past half hour of their lives.

When their mother invited them home for lunch, they’d thought nothing of it, of course. Sullivan and Truman rented apartments nearby and ate here regularly, and although Rex lived in Brooklyn, he often dropped by. No, the invitation was nothing special, but after lunch, Sheila had shown them a receipt from the lottery board whom, she said, would be contacting them. She’d put the money she’d won into a special account already, but since Sullivan, Rex and Truman would be the probable beneficiaries, the board needed them to sign some papers. “The money’s yours, boys,” Sheila had finished brightly.

Truman was still watching her in stunned silence, when she’d added, “But only if you marry within the next three months.”

She’d kept flashing that brilliant smile as if she’d said the most reasonable thing in the world, and Truman had shaken his head. He loved his mother, they all did, but she was the world’s most unlikely woman to birth three cops, or to have married one. Every inch the Earth Mother, she stayed too busy to do more than twist her long gray hair into a haphazard bun, and she favored ankle-length skirts, vests and sandals that she wore with socks. Unconventional to say the least, she had a ready smile and heart of gold that allowed her to not only mother her own sons, but often the men in the precincts for which they worked. Her special home-made doughnuts, complete with blue-and-gold icing, were legendary.

“Ma can be a little nuts sometimes,” admitted Rex when his chuckles subsided. “But it’s a good kind of nuts.”

Truman had his doubts. During lunch, the first thing he’d said was, “Where did you get an idea like this, Ma?”

“Oh, I read about such things all the time,” she’d assured, nodding toward a novel she’d left open on a chaise longue.

“In books,” Truman had stressed. “Novels.” Half-afraid his mother hadn’t understood, he’d added, “Books are make-believe.”

“Not anymore, son.” Laughing, Sheila had wagged a finger in warning. “No fake marriages, either, boys. And you have to be in love. You can’t cheat and get married, planning to divorce later. Nor can you tell your prospective brides that marrying them will make you rich.”

“That takes away a bargaining chip,” muttered Truman, who had absolutely no intention of getting married. At least not for love. For money, sure. But he’d nearly married for love once—and never again.

Frowning, Sheila had added, “And unless all three of you find brides and marry within the three months, nobody gets any money at all.”

“We all three have to get married,” clarified Truman.

She’d nodded. “Yes. And in order to make sure your future wives don’t know about the money, we’ll have to keep this hush-hush. If anyone, including the newspapers, finds out I won, I’m going to donate the money to the Research Foundation of the Galapagos Islands.”

“The Galapagos Islands?” Sully had repeated in disbelief.

Their father, like Sully, was rational to a fault. He’d put an end to the ridiculous plan. “Where’s Dad?” Truman had demanded.

For a moment, their mother had looked distant. “Work,” she’d murmured. “He’s been putting in a lot of overtime. I think a big case is breaking, and I’ve been meaning to talk to you three about it. I’m not sure, but I think your father might be in some sort of trouble—”

“Have you talked to him about this?” Rex had interrupted, since this was hardly the first time Augustus Steele had been in trouble or working too hard. The man was always putting out fires downtown in the commissioner’s office at Police Plaza.

“No,” Sheila had returned. “I haven’t talked to him, and now that you mention it, I’d better make another stipulation. If you tell your father about this, the deal’s off, and every dime goes to the Galapagos Islands.”

Sully’s expression was usually unreadable, but his lips had parted in frank astonishment. “You’re not telling Pop you won the lottery?”

“Nope,” Sheila had returned, twisting a leather wristband to get a better look at a watch that had more gadgets on it than the dashboard of a Ferrari. “And neither are you. Now, boys, I’ve got a few more minutes before my meeting with C.L.A.S.P.”

Truman had gaped at her. How could she run off at a time such as this? “C.L.A.S.P.?”

“City and Local Activists for Street People,” she’d clarified, her lips pursing in displeasure. “The mayor cut funding again. Three more mental health facilities closed this morning, and hundreds of people have been released with nowhere to go. We’re opening a new women’s shelter in the meat-packing district. This week, I’ll post flyers in your precincts, asking for clothing donations. I’ve been putting them all over town for months. Everybody needs to contribute.”

She’d paused, shaking her head in disgust. “Even Ed Koch and David Dinkins were better than this,” she’d said, her tone maligning the previous New York mayors. “Anyway, before I leave, why don’t you go to Sullivan’s room and think over my proposition? Let me know if you want to—” Pushing aside her pique over New York City politics, she’d grinned, enjoying the catbird seat. “Accept my challenge.”

She hadn’t looked the least bit fazed by her remarkable win, and Truman guessed it was largely because she was the mother of three cops. Nothing ruffled her. “I’ll be anxious to see who makes it to the finish line first. You boys with your brides, or my poor tortoises in the Galapagos.”

“Tortoises,” Truman whispered now.

“What else?” murmured Sullivan.

Preserving natural animal habitats in the Galapagos Islands had long been their mother’s obsession, so the brothers had been weaned on stories about the mysterious volcanic islands in the Pacific. Just off the coast of Ecuador, the islands were close to a mainland that was magical in its own right, with a history of Inca warriors, Amazon explorers and Spanish conquistadors. Nature had been left to thrive on its own in that lost part of the world, and the islands that had inspired Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the 1830s were now home to wildlife that existed nowhere else on earth.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Truman said to his brothers now, feeling a twinge of guilt. “I’ve got nothing against sea turtles.”

Sully chuckled. “Me, neither.” He let a beat pass, then added with irony, “It’s the marine iguanas that get on my nerves.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” joked Rex. “Penguins can be such a pain.” He sighed, adding, “What’s happening in the islands is pretty nasty. Ma’s right. They’re still trying to clean up the last oil spill. A couple days ago, some ship, I think it was called the—”

“Eliza,” supplied Sullivan.

“The Eliza,” repeated Rex. “Right. It ran aground near a nesting area for sea lion pups.”

“Ma’s serious,” Truman reminded. “Are we doing this or not?”

Rex stared. “We can’t find soul mates in three months.”

“She said wives, not soul mates,” argued Truman.

“To me, a wife would be a soul mate,” returned Rex.

“Oh, please,” muttered Truman. As the only Steele who’d ever given true love a whirl, he knew better.

“Ma said we have to be in love,” Sully put in.

“For five million dollars,” Truman said, calculating a third of the pie, “I think I could lie.”

Sully tried to look shocked. “To your own mother?”

“As if I don’t have enough on my plate…” Truman raked a hand through light brown hair, the longest strands of which traced a strong jaw.

Rex raised an eyebrow. “Why? What happened?”

“Coombs is trying to put me on a two-week drive-along with a reporter from the New York News.” Coombs was Truman’s boss at Manhattan South precinct.

“Smart move. You’re the best-looking cop in the NYPD,” said Sully without rancor. “You’ve got a strong arrest record, and you’re chasing the limelight, little brother.”

Truman tamped down his anger. It was tourist season, which meant the mayor, the News, and the NYPD were seeking ways to curb the mob hysteria that inevitably came with summer heat waves, and to assure people that New York City was the perfect place to bring kids on vacation.

Truman wasn’t interested in the public relations article. He was determined to solve the city’s latest, high-profile case, which had been dubbed the Glass Slipper case by the New York News. The case had been assigned to him, but if he wound up doing a drive-along with a reporter, he wouldn’t have time to work it. He had too many other more important cases on his desk. The Glass Slipper was special, though, since it involved film celebrities and rock stars. Cracking it would garner Truman enough attention to get him his full detective’s shield. He loved his work, hated bogus cases, and was tired of moving up the rung so much more slowly than his brothers.

“And now I’m supposed to find a wife?” he muttered.

“Speaking of women and your patrol car,” said Rex, fishing in his pocket for a piece of paper. “Some girl left this under your windshield wiper. I brought it in. Maybe you can marry her.”

Truman glanced down at a note written in lipstick. Officer Steele, I saw your car. Nice meeting you yesterday. I’d really like to get together for dinner. Call me. Candy.

Truman had enjoyed meeting her, too. Unfortunately, he’d been arresting her for being drunk and disorderly. Carefully pocketing the note in case his search for a bride came to that, he leaned in the doorway, glancing away from Sully’s room and the model planes and boats Sully had spent hours building as a kid, into Rex’s room, which was full of books, and then to his own, which was decorated with sports trophies and school pennants.

“Candy’s cute, huh?” asked Rex, referring to the note.

“Drunk and disorderly,” corrected Truman.

“But there will be others,” Sully said dryly, making Truman smile. Truman never beat his older brothers at anything, but Sully was right. Truman attracted the most women. He enjoyed their company, too. He just didn’t want to set up housekeeping. Until now. How would his mother know whether or not he really loved his bride? She wouldn’t, he decided, a new goal forming in his mind. In addition to cracking the Glass Slipper case, he’d be the first Steele to marry—though not for love, of course.

“As soon as my latest case broke,” Rex was saying, “I was going to take vacation. I’ve racked up four weeks leave time.”

Sully raised his eyebrows. “Where?”

Rex offered a typical Rex response. “Wherever the wind takes me.”

“It better be some place with women,” Truman warned. “Seeing as we’ve only got three months to get married.”

Three months. Or they’d lose fifteen million dollars. “Can you guys believe this?” Sully said rhetorically. The way he saw it, they might as well hand the money over to the turtles right now. His last serious, long-term relationship had lacked passion he couldn’t live without, and when he’d found passion, the relationship hadn’t included a meeting of the minds.

Absently, Sully reached for a shelf, lifting one of the models he’d made as a kid—a ship inside a bottle. Rarely given to whimsical behavior—that was Rex’s domain—Sully imagined himself writing a letter detailing what he wanted in a bride, putting it in the bottle and tossing it into the Hudson River. All his life, he’d done the tried and true…the dinner dates, boxes of candy, bouquets of flowers, and he was still single. For years, he’d wanted the kind of relationship his parents shared. Why not send a message in a bottle…?

“It’s us or the turtles,” Truman prompted.

“Well, Truman,” returned Sully, thoughtfully turning the bottle in his hands and surveying the ship inside, a classic Spanish galleon of a sort that had comprised treasure fleets and been manned by sixteenth century pirates. “Maybe the reporter from the News will be female, and you can marry her.”

“Right.” Truman smirked. “The News always sends a guy on the drive-alongs.”

“YOU’RE SENDING ME ON A drive-along? With the NYPD? For two full weeks?” Trudy Busey didn’t try to hide her disappointment. She told herself she was a trained professional and needed to prove she could be cool under fire, but as she glanced around the table and took in her co-workers, among them Scott Smith-Sanker who, as usual, was getting all the juicy assignments, she decided there was only one way to claim turf in a newsroom—fight.

The city editor, Dimitri Slovinsky, otherwise known as Dimi, raised a bushy eyebrow. Overweight, over fifty and slovenly in appearance, only the sharp bite in his dark eyes gave away his superior intelligence. “Are you having a problem, Busey?”

She braced herself, wishing Dimi would trust her with bigger stories. Scott wanted her to quit the News. And her own father, who owned the Milton Herald in West Virginia never took her dreams seriously. Yesterday, Terrence Busey had the nerve to call the News a “mere tabloid.”

This, she thought now, from the man who, before semiretirement, had handed the Milton Herald over to her brothers, Bob and Ed. The weekly’s circulation had dropped by 50 subscribers, and now only went to 300 households. None of which would be happening if her father had named her his successor. His lack of belief in her hurt, cutting to the core. Why couldn’t he see she was a good reporter? Why couldn’t Dimi?

Despite her loyalty to the Milton Herald, Trudy loved everything about this paper that had started in 1803 as the New York Evening News and faithfully served New York ever since, becoming the longest continuously running daily newspaper in America. She loved how the smell of ink filled her nostrils as she pushed through the smudged glass doors every morning carrying coffee from Starbucks. She loved being greeted by the sight of harried reporters who’d been awake all night at desks strewn with overflowing ashtrays, foam cups and files.

Without even looking, Trudy could name the blowups of past News covers hanging on the walls: the Kennedy Assassination, the Lindbergh baby, the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the murder of mob kingpin, Paul Castellano…

The News was a hub. Its reporters had earned nearly forty Pulitzer prizes, and every time she walked through its doors, Trudy realized her finger was on the pulse of America. She had no interest in the conservative New York Times. She’d been raised on a hometown paper, and the News had hometown roots—in the country’s biggest hometown.

“Dimi,” she began, fighting frustration, but determined to defend her position. “There are so many great stories begging to be written. The drive-along isn’t the best use of my time.”

It was an understatement. The drive-along was pure fluff. Human interest. Good publicity the News generated every year as a favor to the mayor at the beginning of tourist season.

Dimi eyed her. “What did you have in mind?”

“The Glass Slipper story.”

“Scott’s on that.”

Of course he is. She tried not to react, but the mere mention of Scott Smith-Sanker’s name sent her through the roof. If he scooped her once more on a story that was rightfully hers, she was going to implode. “Well, what about the lottery?” she suggested. “Whoever claimed the fifteen-million-dollar jackpot wants to remain anonymous. We need to find out who it was. After all our hype, the public wants to know.” The story was every bit as important as the Glass Slipper.

“Ben’s following up on the lottery.”

It wasn’t easy to tamp down her anger. “There was a murder just twenty minutes ago on the East Side. What about that?”

“Keith’s headed there already.”

“Okay,” she said patiently. “It’s not a city story, but we need to follow up on the Eliza.” She glanced toward a News cover showing the oil tanker that had run aground near the Galapagos Islands.

“A stringer’s on it.”

Not about to worsen the situation by making a scene, Trudy waited until the meeting was over and the others filed out before turning to her boss and saying exactly what was on her mind. “If this is the kind of work you want me to do, why did you even bother to hire me?”

“Your assignment’s a good one, Trudy.”

“It’s busy work,” she pushed back.

“High profile. You’ll liaise with the mayor.”

Maybe. But that wasn’t the kind of reporter she was meant to be. She’d had this same conversation with her father and brother for years, whenever they handed her grunt work, hoping to discourage her from working for the Herald. The ploy had worked. She’d left the Herald in a huff. But she was not leaving the New York News, and she intended to get real stories. The hard stuff.

“The Glass Slipper,” she reminded, not usually one to toot her own horn, but understanding she no longer had a choice. “I thought of calling it that. The name sold papers, Dimi. The allusion to Cinderella and Prince Charming captured the imagination of our readership.”

The case had begun two months ago when wealthy, famous female New Yorkers began reporting the bizarre theft of expensive, custom-made shoes. At this point, over a hundred pairs were missing from over a hundred apartments, and the police, unable to discern a motive and confused by how the thief gained access to so many well-guarded homes, were hot to solve the crimes.

Trudy had written the News’s first headline, “Can These Cinderellas Find Their Glass Slippers?” Her next was, “Who is Prince Charming?” Ever since, along with the growing lottery jackpot, the story had captured the imagination of news-hungry New Yorkers. Newspaper sales had skyrocketed.

“Circulation’s up,” she continued. “And we’re getting more hits online, too.”

“Your contribution’s been noticed,” Dimi conceded. “And soon, Trudy, we’ll have a hot tip that’s—”

“Right for me?” She wasn’t in the habit of cutting off her boss, but she’d reached the end of her rope. “I’ve been here two years. I’ve been patient. I’ve gophered. I’ve gotten coffee, picked up lunch and worked double time. Just how many dues do you expect me to pay before you’ll let me wedge a toe in your old buddy club?”

Dimi considered. “You think this is a chauvinist atmosphere?”

“How could I not feel discriminated against?” she returned, not backing down. She’d have left before now, but she wanted the experience of working on the nation’s longest running daily, even if she cursed the ambition that made her want to conquer it. She could almost hear her father’s voice. “You’re cute, Trudy. If you want to go into news, why don’t you try television?” Occasionally, he’d generously point to weather girls as models.

Trudy Busey was no weather girl.

Dimi stared at her as he peeled silver foil from a roll of antacids and began chewing one—all the while thinking he ought to give in and do what doctors kept telling him: lose weight. But then, doctors didn’t understand the pressures of being an editor in a big-city newsroom, no more than the stress of managing people like Trudy. She wanted the Glass Slipper and lottery stories? Well, the distressing fact was, she deserved them.

“Why did you bother to hire me?” she asked again.

Because she’d possessed two main prerequisites for the job, Dimi thought now. She was eager and pushy. During their interview, she’d been fiercely determined. Along with college newspaper clippings, she’d submitted human interest stories she’d written for her father’s newspaper, and Dimi easily read between the lines. Her father didn’t want her in the news business, but she was hell-bent on succeeding, not to mention jealous of two, less talented brothers who’d been handed the Milton Herald on a platter.

Dimi had wanted to give her a chance. Trouble was, one look at Trudy, and Dimi wished he was thirty years younger, fifty pounds lighter, and a much nicer guy. She was the one person in years who’d actually located his soft spot. Once he’d given her the job, he simply couldn’t stand to set her loose in a town he feared would eat her alive.

She was petite. Five foot four, with smooth skin and fine, yellow-blond hair that just touched her shoulders. Every time he looked at her, Dimi understood her father’s sentiments. There was something pure and untouched about her, evidenced by how Scott Smith-Sanker slid stories out from under her with the ease of a well-lubricated machine. Dimi feared, once she was on the street, her soft West Virginia twang would peg her as an easy mark, too. How could he train her wide, adventuresome eyes on a crime scene? Or put her in a position to get chewed up by angry cops and hustlers? Leave that to the Scott Smith-Sankers of the world, Dimi thought now. Guys like Scott were born and bred for life’s ugliness.

Trudy had been watching him, trying to guess what was going on inside his mind, and now she told herself not to say it, but then did. “Please,” she said, hating begging. “At least give me the lottery story. Or the Galapagos oil spill.”

Looking guilty, he shook his head. “You’re on the drive-along with a cop from Manhattan South named Truman Steele. And you better get moving.”

She was stuck with a poster boy for the NYPD, Trudy thought angrily as Dimi gave her the rundown. Truman Steele was from a family of cops, with a father in the Commissioner’s office in Police Plaza and two brothers in downtown precincts. Her mind still on the Galapagos Islands, the lottery and the Glass Slipper story, she glazed, regaining her attention when Dimi said, “Manhattan South is—”

“I know where the precinct is,” she snapped, her voice steely as Dimi thrust a file into her hand.

Right before tucking it under her arm, she glimpsed a photo of the most interesting-looking man she’d ever seen. Her heart clutched. Truman Steele was bare-chested and seated in the open door of a patrol car. Sucking in a breath, she realized this was one of the candied photos the NYPD’s public relations department had posted around the city last year, depicting cops out of uniform, so they’d seem more accessible to the public.

Her eyes skated over a smooth, muscled chest, unable to ignore that the nipples were erect, as if the picture had been taken on a cold day. The face was unusual in a way she’d rather not notice. Very arresting. Flyaway wisps of straight, light brown hair fell longer than the police force usually allowed, with the longest strands tracing a hard, implacable jaw. His skin was taut, molded over noticeably rigid bones, and he had a wide mouth and nose, which, along with dark, cautious eyes that tilted upward, made him appear to have Asian blood, though he was clearly caucasian.

That strange mix of features came together in a one-of-a-kind face that would have been eye-catching enough without the quality of the expression. Instead of looking as if he was posing for a photo, Truman looked as if he were staring across a candlelit table, his lips parting to ask a woman if she wanted to make love. Even worse, given the composition of the picture, it was only natural that Trudy’s gaze follow the downward arc of an arm, to where a wrist rested on a jeans clad hip. Loosely curled fingers unintentionally covered the V at his open legs. Belatedly realizing her eyes were fixed on that spot, she quickly glanced away, not about to acknowledge the disappointment she’d felt when she hadn’t…seen more.

“I remember when the NYPD took these press kits photos of the cops,” she managed, telling herself she wasn’t affected.

“Do you?” Dimi said, looking mildly amused.

“Yes,” she said succinctly. “I do.”

Still smiling, Dimi added, “Don’t forget you’re on the job, Busey.”

“I won’t,” she assured simply. As a rule, Trudy kept men at arm’s length. Between fighting her father and brothers, not to mention Dimi and Scott Smith-Sanker, she found it hard enough to realize her ambitions.

The last thing she needed was another man dragging her down.