Читать книгу The Begum's Millions - Jules Verne - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

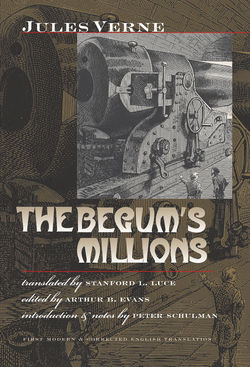

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

“Without him, our century would be stupid,” the novelist René Barjavel once wrote.1 From the magical aerial adventures of the balloonists in Cinq semaines en ballon (1863, Five Weeks in a Balloon) to the underwater discoveries of Captain Nemo, Verne has never ceased to stimulate the imagination of readers from every point of the globe. It is no small wonder that Verne, according to UNESCO, ranks fourth among the “most translated authors in the world” (behind Walt Disney Productions, Agatha Christie, and the Bible).2 Verne’s famous — if not apocryphal — statement “Whatever one man can imagine, another will someday be able to achieve” has been an inspiration to many who have looked to his works as a beacon for progress and wonder. Alas, one can read that quote with another message in mind as Verne’s visions in The Begum’s Millions (1879) — such as Stahlstadt, the horrifying protofascist state, or Schultze, its megalomaniacal leader — have come true all too often in our own cataclysmic twentieth century. As I. O. Evans remarks, the novel “contains some of Verne’s most striking forecasts. He was probably the first to envisage … the dangers of long-range bombardment with gas shells and showers of incendiary bombs.… He regarded other developments as even more disquieting than such weapons: the attempt of German militarism to dominate the world and the rise of a totalitarian state, rigidly directing its people’s lives and infested by political police.”3

Indeed, when a string of relatively happy tales — such as Voyage au centre de la terre (1864, Voyage to the Center of the Earth), De la Terre à la lune (1865, From the Earth to the Moon), and Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1873, Around the World in Eighty Days) — is interrupted by as frightening and enigmatic a text as The Begum’s Millions, Verne’s traditionally upbeat image as a lover of progress and technology must be questioned. Despite Dr. Sarrasin’s declaration that the millions he is inheriting will go exclusively toward Science and the building of a utopian community — “the half billion that chance has placed at my disposal does not belong to me, but to Science!” — The Begum’s Millions is an extremely cautionary tale, which features Verne’s first truly evil scientist, Herr Schultze, and stands as the only one of his works to present both utopian and dystopian visions of society. Whereas Verne’s friend and publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel had steered him away from writing grim dystopian novels in favor of more cheerful adventures after he rejected Verne’s first — and recently rediscovered — novel Paris au XXème siècle (1994, Paris in the Twentieth Century), The Begum’s Millions ushers in a more pessimistic period in Verne’s writing that will reach its peak in his last novels, such as Maître du monde (1904, Master of the World), in which Robur, the once visionary and poetic inventor of the helicopter-airship The Albatross, becomes a psychotic megalomaniac who seeks to take control of the world through his new invention, The Terror. Curiously, as if to remind his readers of the terrible lesson of The Begum’s Millions, Schultze is alluded to at the very beginning of Robur-le-conquérant (1886, Robur the Conqueror), when Robur’s mysterious airship is mistaken for the huge missile-satellite that Schultze had launched into orbit and that circles continuously around the Earth.

That Verne painted more sobering pictures of the world later on in his career comes as no surprise, however, for readers of his early novel Paris in the Twentieth Century, in which he portrays a stifling hegemony in a Paris of the 1960s where creativity is frowned upon while greed and business reign. It took over a hundred years for Paris in the Twentieth Century to find the light of day because Hetzel had rejected it for being too drab and depressing. Perhaps an older Verne, grown weary of the world’s wars and out-of-control capitalism, could no longer suppress the more cynical inclination that was growing within him.4 As he would write to his brother, “All gaiety has become intolerable to me, my character is profoundly altered, and I have received blows in my life that I will be unable to recover from” (August 1, 1894).5

Although different in many ways from his earlier endeavor, The Begum’s Millions remains one of Verne’s most intriguing and exciting novels. And it came at a time (after France’s humiliating defeat to the Prussians in 1870) when Verne’s young and older readers alike desperately wanted a moral boost. Who better than Verne to lift the morale of a nation in dire need of inspiration? Certainly the Nazis were aware of the novel’s potential power to stir an enemy nation when they had it removed from German libraries during World War II. Similarly, as the Germans began remilitarizing the Ruhr in the 1930s, Gaston Leroux knew that The Begum’s Millions could serve as a “wake-up call” for his countrymen, when he referred to Verne’s novel at the beginning of Rouletabille chez Krupp (1933, Rouletabille at Krupp’s). As France urgently required a reminder of the horrors of World War I, Leroux warned of another Schultze rising on the other side of the Rhine. When one of his characters dismisses reports of a new German secret weapon similar to the one Schultze creates in The Begum’s Millions, “But that’s a Jules Verne yarn you’re telling me there, my dear genius … I read it when I was in school! It’s called The Begum’s Millions!,” the narrator feels compelled to interject: “We live in a time when all of Jules Verne’s imaginings — on earth, in the air, and beneath the seas — are being realized so accurately and so completely that one can no longer be surprised if that novel enters the realm of reality as well!”6 Alas, if only Verne could have been wrong in his predictions for The Begum’s Millions, perhaps our twentieth century would not have been so bloody! Yet, just as Verne had been prescient in his description of Stahlstadt, the evil “City of Steel” of the novel, he hardly seems to endorse his utopia in the end either, as it too is a state governed by constraints and obsessions.

When asked by a reporter toward the end of his life if he believed in “progress,” Verne could only give a rather “Zen” response. As The Begum’s Millions demonstrates, progress can be a very subjective term indeed. “Progress toward what end?” Verne asked, before answering:

Progress is a word that can be abused. When I see the progress the Japanese have made in military affairs, I think of my novel The Begum’s Millions, one half of a colossal fortune went to the founders of a virtuous community, while the other half went to the followers of a dark genius whose ideal was expansion through military force. The two communities were able to develop within the possibilities made available through modern science — one aiming for harmony and knowledge, the other going in a different direction altogether. And so, in which direction will our own civilization go?7

While, unfortunately, only the future will be able to answer Verne’s question, history has already decided the direction that the twentieth century has gone. And one can only hope that the twenty-first century will heed the warnings contained in works such as The Begum’s Millions and evolve toward a more harmonious, peaceful world.

The Novel within the Novel: The Story Behind The Begum’s Millions

How did Verne get the idea for The Begum’s Millions, a novel that is traditionally seen as a “turning point” in his work, as he slowly began to shift from being a sunny optimist to a guarded pessimist? In fact, the story surrounding the novel’s origins would be worthy of a novel in and of itself.

The first version, which was originally called L’Héritage de Langévol (The Langevol Inheritance), was written by a certain Paschal Grousset, a Corsican author, reporter, and revolutionary who wrote under numerous aliases such as Philippe Daryl, Leopold Viray, and Tomasi, but was best known as André Laurie, a pseudonym he used to write a series of successful young adult adventures. Grousset led an exciting and colorful life in his own right. He had been sent to prison in 1870 for attacking Pierre Bonaparte with his friend Pierre Rochefort but was released six months later during the Second Empire. Soon after, he fought alongside the Paris Commune, was arrested once again, and was sent in 1872 to a penal colony in Noumea, New Caledonia, from which he escaped with his friend Rochefort in a daring and perilous breakout. After living in the United States for a while, he went to London where he wrote The Langevol Inheritance. Through the auspices of the abbé de Manas, who served as his agent, he managed to sell his manuscript to Hetzel for 1,500 francs in a series of clandestine transactions, since Grousset was still a wanted man. In turn, Hetzel asked Verne to rework and rewrite the novel, as it had some serious flaws. Hetzel knew that Verne’s “magic touch” would be able to make the novel into a success. Grousset/Laurie would go on to ghostwrite two other novels under this arrangement: L’Etoile du sud (1884, The Southern Star), set in South Africa and originally called “The Country of Diamonds,” and L’Epave du Cynthia (1885, The Salvage of the Cynthia), for which Laurie was finally able to share credit publicly with Verne because the Communards had been pardoned and he no longer needed to stay in hiding.

Verne’s Imprint

Although Laurie was delighted and honored to have his manuscript be a part of Verne’s Voyages extraordinaires,8 Verne thought the book needed a lot of work and proposed several changes in his correspondence with Hetzel. As Verne describes it himself, he considered The Langevol Inheritance to be both unbalanced and unrealistic:

Above all, I have to tell you that in my opinion, the novel, if it is indeed a novel, is in no way complete. The drama, the conflict, and consequently the interest are absolutely missing. I have never read anything so poorly put together, and at the moment when our interest could be developing, he suddenly drops the ball. There is no doubt about it, the interest is in the conflict between the cannon and the torpedo;9 and yet one is never launched and the other doesn’t explode. It’s a complete failure. L’abbé10 drives me crazy with his new weapon system, which I’ll discuss later, and I don’t see anything working at all. This is a big mistake as far as the reader is concerned.11

Among Verne’s many comments to Hetzel about what was wrong with the original manuscript, he said that he was especially concerned with the passages he thought were not believable or accurate. From a purely narrative point of view, he did not believe that the contrast between the French utopia, which he referred to as “The City of Well Being” and the Steel City worked because Verne thought that Laurie’s French city was really too American. Verne complained that “[The City of Well Being], which is hardly described at all except as part of a journal article, which is very boring, does not seem like a French city to me, but an American one. That Dr. Sarrazin [sic] is really a Yankee. A Frenchman, as opposed to a German, would have operated with more artistry than that” (Correspondance, 289). Moreover, in the same letter, Verne refers to the City of Well Being as “that Franco-American” city rather than the nationalistic French one. He also had harsh words for what he considered Laurie’s awkward scenes, such as Marcel’s death sentence and subsequent escape from Stahlstadt, which “should have been superb” but remains “pathetic,” as well as the episode of little Carl in the mines, which Verne thought was tedious because he had already written similar scenes in the Les Indes noires (1877, The Black Indies). Without mincing his words, Verne remarked: “I have never seen such sheer ignorance of the most basic rules of novel writing” (289).

Verne was most concerned, however, with the scientific accuracy of the novel. As someone who researched every detail of even his most extraordinary of Voyages extraordinaires, he was appalled by what he considered to be Laurie’s lack of understanding of the mechanics inherent in the weapons he was discussing. Since Verne thought that the novel’s main focus was on Schultze’s giant cannon and missile, he had little patience for any sloppiness on Laurie’s part:

If l’abbé proves one thing, it is that he doesn’t know what a cannon is, and that he is unversed in the simplest rules of ballistics. I’ve spoken to some competent people about this subject! It’s just a rag of absurdities, from top to bottom. Everything has to be redone. Not even the invention of an asphyxiating gas shell is new. Can you see Mr. Krupp reading this novel. He would just shrug his shoulders! That we mock the Germans, so be it, but let’s not let them mock us even harder. Believe me, when I imagined the cannon in The Moon,12 I stayed within the realm of what is possible, and I said nothing that was not exact. Here, everything is wrong, and yet, that’s what is at the heart of the novel (290).

Verne goes on to repeat his claim that all of Laurie’s descriptions were mathematically and scientifically erroneous and further criticizes the absurdities of the plot, which he felt ended too abruptly: “It is as though it were being performed on stage and the hero had been hit on the head with a chimney in order to clumsily end the play” (290).

For his part, Hetzel was stunned at Verne’s harsh criticism: “I knew that there would be parts of the novel that you would want to bypass or that would really bother you as you came across them. But I didn’t expect this complete demolition” (293). Yet, Hetzel, in his continuing role as fatherly mentor and pragmatic editor, was nevertheless able to nudge Verne into reconsidering this project for reasons that Verne might have overlooked in his first reading of the novel. In terms of the narrative, for example, Hetzel urged Verne to see the novel in political and philosophical terms rather than simply scientific ones. For Hetzel, the crux of the story was centered on the notion of the two cities: a totalitarian state revolving around an all-powerful tyrant, and the other, a free, open society based on reason and democracy. “The cannon is everything in the first state,” Hetzel remarked, “the torpedo is just an in case of in the second” (292). Hetzel was especially fascinated with the political structure of Stahlstadt and disagreed with Verne’s assertion that the ending, in which Schultze is frozen just as he is about to launch a devastating attack on France-Ville, was too sudden. As Hetzel explains, when Schultze accidentally auto-destructs, it is an “explosion of both the machine and the man. Everything dies with him, precisely because of that abuse of the concentration [of power in the hands of one individual]. It’s the despotic ideal that collapses, that necessarily had to abort, and that logically aborts. Not because a brick falls on his head, but because, in that system, the brick is inevitable and logical” (292).

Hetzel also disagreed with several other narrative points that Verne critiqued in the original version. While Verne thought that Marcel’s initial entry into Stahlstadt was boring, and his escape ludicrous, Hetzel maintained that they were both important, and that his entry into the evil city, far from being tedious, was essential. While agreeing that the manner in which Laurie presented his ideas needed a great deal of improvement, Hetzel argued that Marcel’s penetration into Stahlstadt could be not only effective but also crucial to the novel as a whole. “On the contrary,” Hetzel maintained, “[Marcel’s entry into Stahlstadt] was the part that seemed to me the most worthy of what readers might consider to be particularly Vernian” (292). While Hetzel also pointed out some of Verne’s other criticisms that he disagreed with, such as the scene of little Carl in the mines (“As for the episode of the little worker — which is just one episode — it can’t harm the novel at all because it’s quite nice — and let me add that it existed in its own right, without any changes, in the first manuscript [of The Langevol Inheritance] which preceded The Black Indies” [292–93]), he ultimately gave Verne carte blanche to do as he pleased: “If, after all of this, you conceive of an entirely different book that would be better and in which the premise reduced to a question of science would be more apt to give you a good story […] the abbot’s book would be no more than a fifth wheel in the carriage of your affairs” (293). In an odd sort of coda to his letter, Hetzel felt obliged to condense his ideas into two sentences, which underline the intensity of the nationalistic Franco-German dialectic that would be at the core of Verne’s novel: “Summary: Germany can break up by too much force and concentration. France can quietly reconstitute itself by more freedom” (293).

While Verne and Hetzel would exchange further letters regarding the technicalities of the novel, each of them made certain compromises that enhanced the final version. Verne, for example, dropped his obsession with the scientific veracity of the cannon and the missile, and ended the novel with Schultze’s accidentally asphyxiating himself in his laboratory just as he is preparing an even more lethal attack against France-Ville (Verne was insistent on this point, much to Hetzel’s delight as he thought it made the text more Verne-like). Although Verne initially wanted to drop the romantic side story of Marcel and Jeanne, which he thought added nothing to the novel, Hetzel persuaded him to include it in at least a perfunctory manner because he considered Marcel too important an opponent to Schultze not to be sufficiently fleshed out as a character. While there are no traces of Laurie’s original version (besides its ending, which has been published in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne), 13 it was apparently presented in two volumes, which both Verne and Hetzel agreed to condense into one. The only other point of contention between Hetzel and Verne revolved around the novel’s title, which Verne thought “said nothing” about the story. Verne juggled several titles in his mind, in fact, in order to arrive at the best “philosophical” definition of the novel: “Parisius or another title like that would work well, but it would have to be in contrast to Berlingotte or another — which is hardly possible. I would like a title along these lines: Golden City and Steel City, A Tale of Two Model Cities” (301). Hetzel, for his part, suggested Steel City (as Verne thought it was more interesting than Good City), but was not convinced that the title could stand on its own. He finally arrived at The Begum’s Inheritance but not without reiterating that the fundamental thesis of the novel had to be grounded on the idea that “steel, force, do not lead to happiness” (302). In the end, what counted the most for Hetzel was that the novel be true to the Vernian spirit and that no one should suspect that another had written it. “Finally, my dear friend,” Hetzel wrote, “it all rests on the idea of not publishing a book that would appear to the public as a book that you could have written but in fact didn’t” (296).

Although The Begum’s Millions did not turn out to be one of Verne’s most successful novels financially, it nonetheless proved to be one his most potent. But did the majority of Verne’s readership consider it to be sufficiently Vernian? According to Charles-Noël Martin, The Begum’s Millions sold only 17,000 copies as compared with most of his previous novels, which averaged around 35,000 and 50,000 in first-run sales.14 Hetzel himself sensed this novel represented something new in Verne’s writing — a new “taste” that he felt confident would add some spice to Verne’s corpus, saying: “My Dear Verne, everything that you have sent me from Begum’s Millions seems to work very well and I believe that it will become a good book, as it has a particular little taste that will do no harm to your (literary) landscape as a whole” (303). What kind of “particular little taste” did Hetzel have in mind? Now with Stanford Luce’s accurate twenty-first-century translation, a new generation of English-speaking readers will be able to judge for themselves how unique and riveting Verne’s complete overhaul of Laurie’s idea truly was. As the old saying goes, a genius can rewrite a lesser writer, but no one can rewrite a genius.

Verne’s “Thanatopia”

“We are sick, that is absolutely certain, we are sick from too much progress,” Emile Zola wrote in Mes haines (1866, My Hatreds). “This victory of nerves over blood has decided our mores, our literature, our whole era.” 15 Can Zola’s famous statement be applied to Jules Verne’s vision of the nineteenth century as well? Although Verne’s most famous works, such as Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1874, Around the World in Eighty Days) or Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (1870, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea), seem to endorse the virtues of technology and progress, the recently rediscovered manuscript of Verne’s dystopian vision of Paris in the 1960s, Paris in the Twentieth Century, speaks out so unsparingly against the dehumanizing aspect of modernity that it also draws attention to his ambivalence toward his own century, which would resurface in The Begum’s Millions. Indeed, the historical context of The Begum’s Millions presents a dour nationalistic picture of two scientists, a benevolent Frenchman and an evil, despotic German, who each inherit millions from a long-lost relative. Whereas the Frenchman, Dr. Sarrasin, creates a utopia on the west coast of the United States called France-Ville, the German, Herr Schultze, builds Stahlstadt, a dystopian factory village bearing an uncanny resemblance to Verne’s hegemonic 1960 Paris. Verne’s descriptions of the “City of Steel” make it clear that “freedom and air were lacking in this narrow milieu” (chap. 7). Stahlstadt is essentially a slave camp similar to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.16 While France-Ville is a peaceful socialist society appropriately situated along the Pacific Ocean, Stahlstadt is a warmongering hegemony, an environmental disaster of a city that manufactures cannons to sell to bellicose nations in general and to Germany in particular: “The general opinion, moreover, was that Herr Schultze was working on the construction of a dreadful engine of war, without precedent and destined to assure Germany worldwide domination” (chap. 7).

While Paris in the Twentieth Century was dismissed by Hetzel as an unpublishable “youthful error,” The Begum’s Millions responded to a general postwar, anti-German sentiment in France. But Verne’s dystopian vision persists as a fulfillment of a general dread of global annihilation that he had to tone down after Paris in the Twentieth Century’s failure. As Arthur B. Evans has explained, the nationalistic, thanatos-driven microcosm depicted by Verne in works like The Begum’s Millions mirrored a more general trend in post–Industrial Revolution France in which the “utopian focus of the French bourgeoisie of the Second Empire and the Troisième République began to shift with the times. The traditional utopian ‘nowhere’ was soon replaced by a potential ‘anywhere’; the pastoral setting by the industrial; personal ethics by competitive expansionism.” 17 As such, The Begum’s Millions can be seen as more than a simple warning of what can happen when science and technology fall into the hands of an evil leader — a warning that would be repeated in Face au drapeau (1896, For the Flag), in which the French scientist Thomas Roch also invents an incredibly deadly weapon of mass destruction, which, after the inventor goes mad, falls into the hands of criminals who seek to use it for piracy rather than geopolitical conquest. In many ways, Verne’s philosophical shift went hand in hand with France’s as well, as Hetzel writes in his famous preface to the first edition of the Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras (1866, Voyages and Adventures of Captain Hatteras): “When one sees the hurried public rushing to lectures that have spread out through a thousand points in France, and when one sees that, next to the art and theater critics, a spot has to be made in our newspapers for reports from the Academy of Sciences, it is time to admit that art for art’s sake is no longer sufficient for our era, and that the time has come for Science to have its place in literature.” Of course, although Hetzel’s reference to science in this instance is meant to be an enthusiastic one, it is clear from a reading of The Begum’s Millions that science can and should never replace the arts. Verne certainly tended to support Rabelais’s maxim: “Science without conscience leads to the ruin of one’s soul.”

“Every time someone dies, it is Jules Verne’s fault,” Salvador Dali wrote in Dali by Dali. “He is responsible for the desire for interplanetary voyages, good only for boy scouts or for amateur underwater fishermen. If the fabulous sums wasted on these conquests were spent on biological research, nobody on our planet would die anymore. Therefore I repeat, each time someone dies it is Jules Verne’s fault.” 18 Ironically, Dali’s mock accusation against Verne could have been written by Verne himself in the sense that a part of his happier and more hopeful writings may have died a little bit by the time he began to pen the nightmarish visions in The Begum’s Millions. That Verne felt compelled to adjust the tone of his adventures is not surprising when one takes into consideration the shifts in paradigms from the early to the late nineteenth century. While the most optimistic of Verne’s early novels endeavored to portray such characters as the young Axel in Journey to the Center of the Earth or the balloonists in Five Weeks in a Balloon as enthusiastic seekers of new geographies and discoveries for the sake of world edification, the realities of the mid- to late nineteenth century were hardly as sunny. More often than not, dreams of global social and political harmony resulted in their opposites, as general disillusionment and skepticism became the norm. Verne too was deeply affected by the changes in the European political landscape. The anxieties he tried to communicate through the aborted Paris in the Twentieth Century soon became realities as financial behemoths led by monopolistic banks and industrialists grew in strength and power. Growing imperialist ambitions led to escalating arms races, which in turn helped to fuel colonialist expansion and the wars needed to either find new colonies or defend newly acquired interests. Cynical treaties such as the Berlin Accords of 1885, which divided Africa among the European colonial empire builders, led to further power brokering rather than idealistic republics. Domestically, workers movements were repeatedly crushed while unpredictable attacks by anarchists and nihilists terrorized the home front. After France’s bitter defeat at the hands of the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war, Verne could only wistfully shake his head as he wrote to a friend: “Yes, this is what the Empire has to show for itself after eighteen years in power: a billion to the bank, no more commerce, no more industry. Eighty stocks that are worth nothing, and that’s without counting those that will collapse any minute. A military government that brings us back to the days of the Huns and the Visigoths. Stupid wars in hindsight.” 19 As Jean Chesnaux has pointed out, the latter part of the nineteenth century was a period during which the wondrous dreams of the early part of the century had to be translated into social responsibility rather than carefree fantasy; shifts in world order created new social demands and needs: “Between about 1880 and 1890, the Known and Unknown Worlds alter their character. Man’s efforts, his Promethean challenge to nature, are from then on expressed through well-defined social entities, clearly analyzed as such. Verne comes face to face with social realities. His scientific forecasts now give place to the problems of social organization, social conditions and the responsibility of scientists towards society; in each case, as we shall see, he reaches a pessimistic conclusion.”20

As a “bridge” novel linking Verne’s positivist and most popular works of the 1860s and 1870s and his more often pessimistic works of the 1880s and 1890s, it is quite appropriate that The Begum’s Millions offers a two-fold vision of society. But the two visions are not polar opposites; even the utopian one has its dark underside. A gigantic inheritance leads to the creation of two states governed by excessively tight restrictions rather than a freedom from constraints and needs that a sudden windfall of cash might be expected to provide. While the peaceful Dr. Sarrasin, designer of France-Ville, benignly declares, “Do I need to tell you that I do not consider myself, in these circumstances, other than a trustee of science? […] It is not to me that this capital lawfully belongs, it is to Humanity, it is to Progress!” (chap. 3), he — like Schultze — creates a centralized and strict state bent on controlling its citizens and destroying its enemies. For Schultze, the enemy is France, whom he sees (in what Chesneaux considers “proto-Hitlerean” terms) as a weak nation of Untermenschen, who must be conquered and then annexed into a greater German Volk; for Sarrasin, the enemy consists of germs, idleness, and uncleanliness, as he founds his city on the principles of Hygiene above all. One city will be driven by thanatos, the other by hypersanitization, or, rather, a thanato-sanitization. On hearing that Sarrasin’s proposed utopia would be founded on “conditions of moral and physical hygiene that could successfully develop all the qualities of that race and educate generations that were strong and valiant,” Schultze counters with a racially charged diatribe suggesting that France-Ville is opposed “to the law of progress which decreed the collapse of the Latin race, its subservience to the Saxon race, and, as a consequence, its total disappearance from the surface of the globe” (chap. 4). A chemist and the author of a treatise titled Why Are All Frenchman Stricken in Different Degrees with Hereditary Degeneration?, Schultze feels compelled to erect his military-industrial dystopia as a countermeasure to Sarrasin’s racial inferiority and dangerously visionary aspirations:

After all, what could not have been done with a man such as Dr. Sarrasin, a Celt, careless, flighty, and most certainly a visionary! […] It was every Saxon’s responsibility, in the interest of general order and obeying an ineluctable law, to annihilate if he could such a foolish enterprise. And in the present circumstances, it was clear to him, Schultze, M.D., Privatdocent of chemistry at the University of Iéna, known for his numerous comparative works about the different human races — works where it was proved that the Germanic race would absorb all the others — it was clear indeed that he was especially designated by the constantly creative and destructive force of Nature to wipe out the pygmies rebelling against it. (chap. 4)

Given that their respective inheritances were brought about by a union between their French mother and German father, they are doomed, almost like Cain and Abel, to violence and war that only the young hero, Marcel Bruckmann, an Alsatian orphan, whose name “bridge-man” implies a link between the two warring nations, can stop. Yet, while Schultze is obsessed with racial purity, Sarrasin is propelled by a fear of microbial contamination — or, rather, germs and science instead of germ-ans and empires. In each case, however, financial capital leads to a lack of freedom rather than an abundance of it. Whether it be Schultze’s death-driven military-industrial complex or Sarrasin’s hygienic but obsessive-compulsive one, Verne seems to suggest that the only choices available to each country would be either a mad and brutal dictatorship or a neurotic one. While seemingly at opposite poles, the fact that both men’s names begin with “S” implies that their roots are fundamentally the same, and that they are nonetheless connected. Moreover, if that “S” could also stand for serpent (snake), as in the Garden of Eden’s biblical snake who leads Adam and Eve into temptation, Verne’s modern “apple” might well be in the form of Capital that Schultze and Sarrasin eat from rather than Knowledge, which they both seem to abuse through Science. As Schultze understands it, finance capital is the most potent secret ingredient for the destruction he envisages:

For all eternity, it had been ordained that Thérèse Langévol would marry Martin Schultze, that one day the two nationalities, represented by the person of the French doctor and the German professor, would clash and that the latter would crush the former. He had already half of the doctor’s fortune in his hands. That was the instrument he needed. […] Moreover, this project was for Herr Schultze quite secondary; it was to be added on to much larger ones he had had in mind for the destruction of all nations refusing to blend themselves with the German people and reunite with the Fatherland. (chap. 4)

If Schultze represents the cliché of a totalitarian Teuton bent on expanding his Reich, his portrayal is also a giant leap for Verne in a growing anti-Germanism that will culminate in Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz (1910, The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz), one of his last books (published posthumously), in which an evil German satanically invents a chemical with which he can become invisible and with which he kidnaps the woman he loves unrequitedly. Although chunks of Storitz were rewritten by his son Michel (who placed it in the eighteenth century, instead of the nineteenth, and gave it a bit of a happier ending), Verne, throughout the novel, never ceases to equate Germans with brutality and evil, and the subjugation of the innocent and brave Hungarians. It is a far cry from the endearingly befuddled Dr. Lidenbrock, Axel’s uncle in Journey to the Center of the Earth, who leads his nephew through an initiation to the center of the Earth with all its treasure trove of discoveries. With The Begum’s Millions, childish yet innocent national rivalries, which had been mitigated by peaceful reconciliations and handshakes in Verne’s previous adventure novels such as the Voyages and Adventures of Captain Hatteras, give way to weapons of mass destruction, potential nuclear annihilation, and economic collapse when rumors of Schultze’s disappearance and death at the end of the novel lead to a flight of capital, unemployment, and rapid decay in Stahlstadt. As Verne describes it, Stahlstadt’s Wall Street–linked financial ruin prefigures the worldwide depression caused by the 1929 crash: “There were assemblies, meetings, discussions, and debate. But no set plans could be agreed to, for none were possible. Rising unemployment soon brought with it a host of ills: poverty, despair, and vice. The workshop empty, the bars filled up. For each chimney which ceased to smoke, a cabaret was born in the surrounding villages” (chap. 15). Once the capitalist strings that kept Schultze’s war machine going are removed, there are no pretenses of production or conquest to keep the workers going, just human suffering, hopelessness, and destitution: “They stayed behind, selling their poor garments to that flock of prey with human faces that instinctively swoops down on great disasters. In a few days they were reduced to the most dire of circumstances. They were soon deprived of credit as they had been of salary, of hope as of work, and now saw stretched out before them, as dark as the coming winter, nothing but a future of despair!” (chap. 15).

Although he managed to suppress the glum and dystopian Paris in the Twentieth Century by not publishing it, and, most importantly, by exercising an almost tyrannical control over Verne’s works in his role as well-meaning but intrusive mentor, Hetzel focused on keeping Verne’s works cheerful enough to continue to attract throngs of young readers. But the city of Stahlstadt — ironically echoing Hetzel’s own nom de plume, “Stahl” — allowed Verne the opportunity to recycle much of his dismal vision of Paris in 1960 that Hetzel had disapproved of. While Verne’s future Paris is dystopian because monolithic banks are obsessed with financial control and perpetually expanding profits at the expense of “useless” romantic individualism, Stahlstadt is a pure industrial machine that exists exclusively for the sake of war and war production. Paris in the Twentieth Century opens with four concentric circles of a vast new commuter rail system that seems to snake around the city in a stranglehold, and the technological innovations that Verne describes in minute detail hold no enchantment for its citizens: “In this feverish century, where the multiplicity of businesses left no room for rest and allowed for no lateness whatsoever […] the people in 1960 were hardly in admiration of these wonders; they quietly took advantage of them, without being any happier, because to see their rushed pace, their frenetic demeanor, their American fire, one could feel that the fortune demon was pushing them on unrelentingly, and without mercy.”21 Similarly, Schultze’s Stahlstadt is also laid out in concentric circles consisting of a stranglehold of walls, gates, security checks, departments and doors:

In this remote corner of North America, five hundred miles from the smallest neighboring town, surrounded by wilderness and isolated from the world by a rampart of mountains, one could search in vain for the smallest vestige of that liberty which formed the strength of the republic of the United States.

When you arrive by the very walls of Stahlstadt, do not attempt to break through the massive gates which cut through the lines of trenches and fortifications. The most merciless of guards would deter you, and you would be required to return to the outskirts. You cannot enter the City of Steel unless you possess the magic formula, the password, or at least an authorization duly stamped, signed and initialed. (chap. 5)

In The Begum’s Millions, the future Paris’s light rail system is replaced by a subterranean railroad meant to transport workers and raw materials toward an industrialized Virgil-like trip to the underworld, a nekya, or descent into hell, for Marcel, the hero who will infiltrate Stahlstadt to save France-Ville:

To his left, between the wide circular route and the jumble of buildings, the double rails of a circling train stood out first. Then a second wall rose up, paralleling the exterior wall, which indicated the overall configuration of Steel City.

It was in the shape of a circle whose sectors, divided into departments by a line of fortifications, were quite independent of each other, though wrapped by a common wall and trench. […] The uproar of the machines was deafening. Pierced by thousands of windows, these gray buildings seemed more living than inert things. But the newcomer was no doubt used to the spectacle, for he paid not the slightest attention to it. (chap. 5)

As Chesneaux has observed, Stahlstadt, far from being the unreal vision of the future dismissed by Hetzel in Paris in the Twentieth Century, is extremely realistic for the late nineteenth century, when steel cities in England, France, and America were generating inhuman working conditions and industrial slums: “[T]he description of Stahlstadt is powerful and glaring with truth. This steel city of the future already foreshadows Le Creusot, the Ruhr, Pittsburgh.”22 As Verne understands it, Stahlstadt is an environmental disaster, hysterically driven by money, greed, and industrial might:

Black macadamized roads, surfaced with cinders and coke, wind along the mountains’ flanks. […] The air is heavy with smoke; it hangs like a somber cloak upon the earth. No birds fly through this area; even the insects appear to avoid it; and, within the memory of man, not a single butterfly has ever been seen. […] Thanks to the power of an enormous capital, this immense establishment, this veritable city which is at the same time a model factory, has arisen from the earth as though from a stroke of a wand. (chap. 5)

Uniform rows of apartments house uniform workers all hired to serve an invisible Baal, whose presence is felt through the roaring of fuming volcano-like smoke stacks: “Here and there, an abandoned mine shaft, worn by the rains, overrun by briars, opens its gaping mouth, a bottomless abyss, like some crater of an extinct volcano” (chap. 5). As Marcel gradually moves up the ladder of the Stahlstadt hierarchy, even earning medals for his efficiency, he finally comes face to face with the nefarious Herr Schultze himself, (who considers him a “find” and “a pearl” [chap. 8]) in a chapter titled “The Dragon’s Lair,” which Simone Vierne views as a type of initiation ritual for the hero.23 Yet it is truly a nekya rather than an initiation as Marcel performs an “Orphic” descent toward Hades, which Dr. Sarrasin describes to him in terms of Manichean peril: “the project would be not only difficult but also perhaps bristling with danger, […] he was risking a sort of descent into hell where hidden abysses might be lurking under his every step” (chap. 16). Yet Marcel’s (and the reader’s) plunge is essentially an economic one during which Marcel, by making a bridge between France and Germany, or rather France-Ville and Stahlstadt, aims to create what might be considered a kind of ideal unified Europe rather than a jingoistic nation-state. Ross Chambers, for example, has pointed out that

Marcel becomes not an individual hero but a figure of his society; and by virtue of his dual, Franco-German identity, the society he figures cannot be either France or Germany but must be something like Europe (a Europe reduced through the ideological limitation of Verne’s vision, to its two major Continental powers). In this reading, the trauma of the French defeat in 1870 would combine with the inhuman conditions brought about by the Industrial Revolution, under the broad aegis of Germany as a figure of death, to form Europe’s own initiatory ordeal — a descent into hell from which a new Europe is destined to emerge.24

It is during Marcel’s tête-à-tête with Herr Schultze that the latter reveals his secret weapons, various crypto-“dirty bombs” that will break up into a myriad of deadly pieces once his gigantic cannon fires them off into France-Ville. Schultze boasts about his invention in terms that are chillingly modern. His claim that “with my system, there are no wounded, just the dead” is preceded by another one, “Every living being within a radius of thirty meters from the center of the explosion is both frozen and asphyxiated!,” and, later, yet another one, “It’s like a battery that I can throw into space and which can carry fire and death to a whole city by covering it with a shower of inextinguishable flames!” (chap. 8). By courageously facing his enemy, Marcel stands up to the rampant French wave of fear regarding Germany’s threat to Europe, which had been propagated through literary and popular political pieces throughout the fin de siècle. With great prescience, Verne touched on a general collective anxiety that would progressively intensify as tensions between Germany and France eventually ballooned into World War I and, later, into World War II.

As Schultze brags about his weapon system, he is also delineating the modus operandi of Stahlstadt itself, which might be seen as more “thanatopia” than dystopia. It is a city pushed toward a kind of nuclear winter avant la lettre rather than world domination. Verne’s worst fears about 1960 Paris are magnified into a diabolical empire firmly based in the realities of the day. Technology is no longer a toy for questing heroes to leap from adventure to adventure; it is rather a direct result of the death drive Freud so accurately pinpointed in Civilization and Its Discontents. As Schultze understands it, Stahlstadt represents the direct opposite of France-Ville’s health mission in its sociopathic goals: “You see! […] We’re doing the opposite of what the founders of France-Ville do! We’re finding the secret ways of shortening lives while they seek to lengthen them. But their work is doomed, for it is from death — sown by us — that life is to be born” (chap. 8). For Schultze, the death drive is a narcotic that fuels his quasi-Nietzchean outlook:

Right, good, and evil are purely relative things, and all a matter of convention. There is no absolute except the great laws of nature. The law of living competitively is just as natural as the law of gravity. Resisting it is utter inanity; to accept it and act according to its precepts is both reasonable and wise — which is why I shall destroy Dr. Sarrasin’s city. Thanks to my cannon, my fifty thousand Germans will easily make an end of the hundred thousand dreamers over there who constitute a group condemned to perish! (102)

Yet, as Yves Chevrel has pointed out, despite all of Schultze’s wickedness, Verne in fact gives him a uniquely grandiose death in which, “mummified like a pharaoh and wildly enlarged in the eyes of his observers, he remains a master of evil even in death. He is the only one of Verne’s heroes — malevolent or benevolent — to survive in this manner.”25 When Verne first read the original version of The Begum’s Millions, he remarked that “the Steel City, because it is described in detail and the hero walks around its streets and brings us with him, is more interesting than the Good City, a city that […] we do not get to visit” (Correspondance, 294). Verne even suggests that Schultze should resemble Captain Nemo, who is also driven by a thanatosian desire in his hatred for civilization above ground, and for a love of the freedom found beneath the seas: “The head of the canon factory should have been a Nemo, and not this fellow who is ridiculous” (184). If Nemo could proclaim his aquatic battle cry: “Only here is there independence, here I do not recognize any master, here I am free!,” there is little doubt that the monstrous Schultze, created ten years later, incarnated the lack of freedom to be found in many late-nineteenth-century industrialized cities.

When Marcel finds Schultze’s frozen, magnified body in his laboratory after the latter’s chemical explosion backfires on him, Verne seems to be warning us of the road to destruction that technology might be leading humanity toward. As Marcel looks upon the frozen Schultze in stunned silence, he notices that he was frozen in the act of writing. While the abandoned Stahlstadt resembles a “cemetery” where “Death alone seemed to float over the city, whose tall chimneys reared above the horizon like so many skeletons” (chap. 16), Schultze’s last words once again irrationally call for the total destruction of France-Ville: “I want France-Ville to be a dead city within two weeks, that no inhabitant survive. A modern Pompeii is what I must have, and at the same time it must provoke the fear and astonishment of the whole world” (chap. 18). Although Schultze’s nuclear-bomb-like missile is spun into space, and provokes a collective sigh of relief from the whole world as it is doomed to orbit the earth forever, Verne seems to warn us that, while the world was spared this time, we must be vigilant in the future, lest new evil scientists try to continue where Schultze left off.

If France-Ville appears more unrealistic in its utopian vision than Stahlstadt in its dystopian one, perhaps it is because Verne believed less in it, or even in its aspirations. Based on a medical fantasy titled Hygeia, A City of Health (1876) by a certain Dr. Richardson, a famous English doctor in his day who outlined a germ-free civilization,26 France-Ville is a society filled with rules and restraints, where sanitation police are constantly watching over its worker-citizens, who live in rigidly uniform houses (with strict rules and measurements). Everything must be in order, as a brochure distributed to its newest citizens states emphatically: “Two dangerous elements of disease, veritable nests of miasma and laboratories of poison, are absolutely forbidden: carpets and wallpaper” declares rule number 8. According to rule number 9, “Eiderdown quilts and heavy bedcovers, powerful allies of epidemics, are naturally excluded” (chap. 10). While “all industries and commercial ventures are freely permitted,” no one is allowed to be idle: “in order to obtain the right of residence, it is sufficient — provided that good references are supplied — to be able to perform a useful or liberal profession in industry, science, or the arts, and to pledge to obey all the laws of the city. Idle lives will not be tolerated” (chap. 10). Every inch of the citizens’ lives is regulated, and the motto that each must subscribe to is a mantra that is exhibited in all of the village’s rules and laws: “To clean, clean ceaselessly, to destroy as soon as they are formed, those miasmas which constantly emanate from a human collective, such is the primary job of the central government” (chap. 10). Parallel to Stahlstadt with its “Central Bloc” that watches over its beehive of productivity, France-Ville is also governed by a “Central Government” that passes down its own edicts for the good of its citizens. Although the government is well intentioned rather than militaristic, the tone of Verne’s description is indelibly linked to that of Paris in the Twentieth Century rather than to the Voyages extraordinaires. Furthermore, while Schultze fantasizes about turning France-Ville into a new Pompeii through his weapons of mass destruction, Verne overdetermines Schultze’s image by also thinking of it in terms of Pompeii, as if to confirm Schultze’s vision: “As for the walls, clad in varnished bricks, they present to the eye the splendor and variety of the indoor apartments of Pompeii with a luxury of colors and longevity which wallpaper, loaded with its thousand subtle poisons, has never been able to rival” (chap. 10).

Although The Begum’s Millions ends on a happy note, with France-Ville not only saved but taking over Stahlstadt and making it economically viable again, it is hard to see it as a “happy ending” in so much as even the victorious “ideal” society is somewhat frightful and industrial productivity remains the highlight of the utopian societies created by the Begum’s fortune. Shockingly, Marcel refers to the defeated Stahlstadt as “the ruin of the admirable institution that [Schultze] had created” and declares that “we must not let his work perish” (chap. 18). Although Marcel and Sarrasin loftily plan on using Stahlstadt’s industrial infrastructure primarily as a deterrent to war — “You will have all the capital you need, and thanks to you we will have in a resuscitated Stahlstadt an arsenal of instruments such that no one in the world will think of attacking us! And, while being the strongest, we’ll also try to be the most just and bring the benefits of peace and justice to everyone around us” (chap. 18) — the novel ultimately proves that capital does fail us and can lead not only to aggression and exploitation, but also to depression, chaos, and potential global annihilation. In fact, the last line of the novel underscores the notion that the real utopian ideal put forth by the victors is essentially a capitalist-industrial one. Stahlstadt is merely converted into a more clement version of its old self: “We can thus be assured that the future will be in good hands thanks to the efforts of Dr. Sarrasin and of Marcel Bruckmann, and that the examples of France-Ville and Stahlstadt, as model city and factory, will not be lost on generations to come” (chap. 20). In this way, the “bridge” implicit in Marcel’s name is one that marries the ethics of the French system with the industrial prowess of the German one in order to create more efficient factory towns rather than dreamy utopian states.

“We live in a time where everything happens — we almost have the right to say where everything has happened. […] Moreover, no new legends are being created at the end of this practical and positive nineteenth century,” Verne writes at the beginning of Le Château des Carpathes (1892, The Carpathian Castle).27 If The Begum’s Millions was not initially one of Verne’s most popular works, and, despite its patriotic and timely anti-German vigor, was not as great a commercial success as his earlier, more Saint-Simonian works, perhaps it is because it ushers in a period of darker visions about government and nations only alluded to in prior novels. It is not surprising that the near apocalyptic struggle between the innocent France-Ville and the ruthless Stahlstadt takes place on American soil, which slowly becomes a land of failed social experimentation and a capitalist free-for-all in his later novels. In Le Testament d’un excentrique (1899, The Will of an Eccentric), for example, America becomes a giant jeu de l’oie game board for the billionaire William J. Hyperbone as his contestants race around the United States in order to win millions of dollars. In L’Ile à hélice (1895, Propeller Island), two millionaires create a floating city, Standard Island, for their comfort, but their dollar-driven utopia soon crumbles under the weight of its citizens’ conflicts. Even the charm of an America that can attempt to reach the moon, and where “nothing can astonish an American” in From the Earth to the Moon,28 becomes dangerously absurd and destructive in Sans dessus dessous (1889, Topsy-Turvy), the cynical sequel to Autour de la lune (1870, Around the Moon), when Barbicane and J. T. Maston recklessly try to shift the axis of the globe in order to mine coal at the North Pole.

“It has often been asserted that the word ‘impossible’ is not a French one. People have evidently been deceived by the dictionary,” Verne writes in From the Earth to the Moon. “In America, everything is easy, everything is simple; and as for mechanical difficulties, they are overcome before they arise. Between Barbicane’s proposition and its realization, no true Yankee would have allowed even the semblance of a difficulty to be possible. What is said — is done.”29 Sadly, what was said often was done — by malevolent figures. As such, the early Verne’s confidence in America may seem naive in light of how he perceived the later part of the century’s excesses and unscrupulous motivations. By the same token, in real life, just as America would be transformed by robber barons and industrial injustices, its image abroad also changed, becoming, little by little, the “péril américain,” a land of exploitation rather than innocent idealism. As Marie-Hélène Huet has noted, the whole Verne-Hetzel literary project deflates in the face of the hard realities of the fin de siècle. Indeed, Verne could no longer afford to merely project cheerfully into the future for, as Huet remarks so succinctly, “the present had invaded the works.”30

When Verne and Hetzel discussed whether the crux of The Begum’s Millions should be centered on Schultze’s weapons and their destructive capability or, rather, on the political-philosophical differences between the two cities, Verne commented that “if we write for 15,000 readers, they’ll want [the former]. If we write for 1,500, perhaps a philosophical thesis might do the trick, but, in any case, it isn’t in the novel as it is now” (Correspondance, 294). Although the novel, in fact, sold around 17,000 copies — a big disappointment at the time, as were many of his later novels with similarly tenebrific undertones — Verne did manage to fuse the two approaches (cannons on the one hand, utopia/dystopia on the other), but his final product remains fascinating for many other reasons as well. Just as Marcel Bruckmann’s name could serve as a metaphor for his being a bridge between the two warring cities and nations, The Begum’s Millions can also be considered a bridge, not only between the “two Vernes” — the early, successful positivist and the later, dour pessimist — but between the two Frances as well. Just as France began the nineteenth century with a “bang” so to speak — as it explored new continents, created new inventions, and fostered a myriad of utopian, socialist philosophers such as Prosper L’Enfantin and Saint-Simon — the weary fin de siècle France would yield a darker, sometimes decadent, but often nervous literature, as a reaction to the disillusionment and exhaustion caused by the failures of such idealistic models. The framework of the happy agrarian utopia of yore would soon give way to the industrial dystopia of the future when the century limped to a close. Verne’s readers, perhaps put off by the negative images of science in the later novels, would also long for those initial “happy days” of Axel, the children of Captain Grant, and Phileas Fogg (the all-time Vernian champion who made Around the World in Eighty Days an international best seller). Although Stahlstadt was ultimately defeated by the forces of good, its somber vision would nonetheless grow more persistent in the latter half of Verne’s oeuvre as the late nineteenth century gave way to a more serious and starker twentieth.

Peter Schulman

Old Dominion University