Читать книгу Robur the Conqueror - Jules Verne - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER

3

In which a new character does not need to be presented, for he presents himself

“Citizens of the United States of America, my name is Robur. I am worthy of the name. I am forty years old, though I look younger than thirty; I am possessed of an iron constitution, indestructible health, remarkable muscular force, and a stomach that would pass for excellent even among ostriches. So much for the physical side.”

And they listened. Yes! The noisemakers were taken aback at once by the unexpectedness of this speech pro facie suâ.1 Was he a madman or a swindler, this personage? In any case, he both interposed and imposed. Not so much as another breath of air from the midst of the assembly, where a hurricane had previously been unleashed. The calm after the storm.

More than that, Robur really seemed to be the man he said he was. Average height, of geometric build—which is to say, a regular trapezoid, with the longer of its parallel sides formed by the line of the shoulders. On that line, attached by a robust neck, an enormous spheroidal head. What animal’s head would it resemble according to the theory of Passionate Analogy?2 That of a bull, but a bull with an intelligent face. Eyes that the slightest contradiction would set ablaze, and, above them, forehead muscles permanently contracted, indicating extreme energy. Short, slightly frizzy hair, of metallic sheen, as if it were a quiff of steel wool. Wide chest rising and falling with the movements of a blacksmith’s bellows. Arms, hands, legs, feet worthy of the torso.

No mustache, no sideburns, a large sailorly beard in the American style—revealing the joints of the jaw, whose masseter muscles must have been formidably powerful. It has been calculated—what has not been calculated?—that the pressure of the jaw of an ordinary crocodile can attain four hundred atmospheres, while that of a big hunting dog can reach only one hundred. The following curious formula has even been deduced: if one kilogram of dog produces eight kilograms of masseter force, one kilogram of crocodile will produce twelve. Well then, one kilogram of this man Robur must have produced ten at least. He was therefore situated between dog and crocodile.

“My name is Robur.”

From what country came this remarkable character? That was difficult to say. In any case, he expressed himself fluently in English, without that rather drawling accent that distinguishes Yankees from New England.

He continued in the same vein:

“And now for the mental side, honorable citizens. You see before you an engineer whose intellectual strength is in no way inferior to his physical. I fear nothing and nobody. My willpower has never ceded to another. When I am fixed on a goal, all America, all the world, would unite in vain to prevent my attaining it. When I have an idea, I intend my views about it to be shared, and I will not accept contradiction. I emphasize these details, honorable citizens, because it behooves you to know me well. Perhaps you find I talk too much of myself? No matter! And now, think carefully before interrupting me, for I have come to tell you things that may not happen to please you.”

A noise like recoiling waves began to spread along the first ranks of the hall—a sign that the sea would soon become rough.

“Speak, honorable stranger,” said Uncle Prudent simply, though he had difficulty restraining himself.

And Robur spoke as before, paying no mind to his listeners.

“Yes! I know! After a century of experiments all leading to nothing, of tests giving no results, there are still some unbalanced minds so pigheaded as to believe in the navigability of balloons. They imagine some sort of motor, electric or otherwise, attached perhaps to their pompous balloon bladders, that could offer enough resistance to atmospheric currents. They imagine they will master an aerostat the same way one masters a boat on the surface of the sea. Because a few inventors, in still weather or something very like it, have succeeded, whether by tilting with the wind or heading into a light breeze, will the steering of lighter-than-air apparatuses be made practical? Come now! You here are a hundred people who believe your dreams will be made real, and who have thrown away thousands of dollars—not into the sea, but into space. Well, all of that is to fight against the impossible!”

Singularly enough, faced with this assertion, the members of the Weldon Institute moved not a single muscle. Had they become as deaf as they were patient? Were they holding back, wanting to see how far this bold contradictor dared to go?

Robur went on:

“What, a balloon—when to obtain a kilogram of lift, you need a cubic meter of gas! A balloon, which claims it can resist the wind using its motor, when the power of a stiff breeze on a sail is equal to the strength of four hundred horses, when it has been shown that the hurricane in the Tay Bridge accident exerted a pressure of 440 kilograms per square meter!3 A balloon, when nature has never constructed any flying creature on such a system, whether that creature is fitted with wings like the birds, or with membranes like certain fish and certain mammals—”

“Mammals?” shouted a member of the club.

“Yes! The bat, which can fly, if I’m not very much mistaken! Is the interrupter unaware that the bat is a mammal? Has he ever seen an omelet made of bat’s eggs?”

At this, the interrupter gave up his future interruptions, and Robur continued with the same bravado:

“But is this to say that man must renounce the conquest of the air and the transformation of the civil and political habits of the Old World by the use of that admirable means of locomotion? Certainly not! And just as he became master of the seas with vessels, by oar, sail, paddlewheel, or propeller, just so he will become master of the atmosphere with heavier-than-air machines—for one must be heavier than air to be stronger than air.”

This time, the assembly went to pieces. What a salvo of shouts from every mouth, all aimed at Robur, as if they were so many muzzles of rifles or cannons! But wasn’t this the inevitable reply to a true declaration of war, shot into the balloonians’ camp? Wasn’t the battle about to begin again between “Lighter” and “Heavier-Than-Air”?

Robur did not bat an eyelid. Arms crossed on his breast, he stood undaunted, waiting for silence.

Uncle Prudent, with a gesture, ordered a ceasefire.

“Yes,” resumed Robur. “The future belongs to the flying machines. Air is a solid point of support. Send a column of that fluid moving upward at forty-five meters per second, and a man could stand on top of it forever, if the soles of his shoes cover a surface area of only an eighth of a square meter. If the column’s speed is brought up to ninety meters per second, he could walk on it in bare feet. And, by pushing away a mass of air at that speed with the blades of a propeller, the same result is achieved.”4

What Robur had just said had been said before him by all the partisans for aviation, whose work must, slowly but surely, lead to the solution of the problem. To Messrs. de Ponton d’Amécourt, de La Landelle, Nadar, de Lucy, de Louvrié, Liais, Béléguic, Moreau, the brothers Richard, Babinet, Jobert, du Temple, Salives, Pénaud, de Villeneuve, Gauchot and Tatin, Michel Loup, Edison, Planavergne, and so many others, is due the honor of spreading these simple ideas! Abandoned and taken up again so many times, they will not fail to triumph some day. To aviation’s enemies, who declare that the bird can only stay in the air because he breathes it in and inflates himself with it, need we wait for their response? Hasn’t it been proven that an eagle weighing five kilograms would have to fill himself with fifty cubic meters of warm air, merely to remain in space?

That is what Robur demonstrated with undeniable logic, amid commotion rising from every side. And, for his conclusion, here are the sentences he threw in the balloonians’ faces:

“With your aerostats you can do nothing, reach nothing, dare nothing! The most intrepid of your aeronauts, John Wise, though he had already made an aerial crossing of twelve hundred miles above the American continent, had to give up his project of crossing the Atlantic! And since then, you haven’t moved a step, not one single step, in that path!”

“Sir,” said the president, forcing himself in vain to keep calm, “you forget what our immortal Franklin said when the first Montgolfier balloon appeared, at the moment when the gas balloon was about to be born: ‘It is only a child, but it shall grow!’5 And it has grown—”

“No, president, no! It has not grown! It has only put on weight—which is not the same thing!”

This was a direct attack on the projects of the Weldon Institute, which had ordained, supported, subsidized the making of a monster-balloon. And so propositions of the following type, hardly supportive in nature, soon crisscrossed through the hall:

“Down with the intruder!”

“Throw him off the platform!”

“Yes, make him prove he’s heavier than air!”

And so on.

But these were only words, not assaults. Robur, impassible, was still able to cry out:

“Progress is not in aerostats at all, citizen balloonians; it is in flying machines. The bird flies, and it is not in any way a balloon; it is a machine!”

“Yes, it flies,” shouted the fuming Bat T. Fyn, “but it flies against all the rules of mechanics!”

“Really?” replied Robur, shrugging his shoulders.

Then he resumed:

“Ever since the flight of great and small flyers was first studied, one simple idea has prevailed: that all that has to be done is to imitate nature, for nature is never wrong. Between the albatross, who flaps its wings at most ten times a minute, and the pelican, who does so seventy times—”

“Seventy-one!” said a jeering voice.

“And the bee at 192 times a second—”

“A hundred and ninety-three!” came the mocking cry.

“And the fly at 330—”

“Three hundred thirty and a half!”

“And the mosquito at millions—”

“No—billions!”

But Robur, interrupted, did not interrupt his demonstration.

“Between these various figures—” he resumed.

“There’s a long way to jump!” returned a voice.

“—there is the possibility of finding a practical solution. On the day Monsieur de Lucy proved that the stag beetle, that insect weighing only two grams, can lift a burden of four hundred grams, or two hundred times its own weight, the problem of aviation was solved. Furthermore, it was shown that wing surface decreases relative to the augmentation of the dimension and weight of the animal. Since then, people have been able to imagine or construct more than sixty apparatuses …”

“Which will never be able to fly!” shouted the secretary Phil Evans.

“Which have flown, or will fly,” replied Robur, not at all disconcerted. “And, whether we call them streophores, helicopters, orthopters, or, in imitation of the French word ‘nef,’ meaning ‘vessel,’ from navis, we employ the word avis and call them ‘efs,’ we arrive at the apparatus whose creation will render man master of space.”

“Ah! the propeller!” riposted Phil Evans. “But the bird has no propeller … that we know of!”

“It has,” replied Robur. “As Monsieur Pénaud demonstrated, in reality the bird acts as a propeller, and its flight is helicoidal. Therefore, the motor of the future is the propeller, the helix—”

“From such an evil spell,

Saint Helix, preserve us!”

sang one of the spectators, who, by chance, remembered that tune from Hérold’s Zampa.6

And everyone took up the refrain in chorus, with such intonations as to make the French composer shudder in his grave.

Then, after the last notes had been drowned in a horrendous uproar, Uncle Prudent, taking advantage of a momentary calm, thought it his duty to say:

“Citizen stranger, until now we’ve let you speak without interruption …”

It would appear that, for the president of the Weldon Institute, those retorts, those shouts, those pointless digressions, were not even interruptions, but a mere exchange of arguments.

“However,” he continued, “I must remind you that the theory of aviation was condemned in advance and rejected by the majority of American and foreign engineers. A system that leaves in its wake the deaths of the Flying Saracen in Constantinople, of the monk Voador in Lisbon, of Letur in 1854, of Groof in 1874, without counting the other victims I’ve forgotten, not to mention the mythological Icarus …”

“That system,” snapped Robur, “is no more damnable than the one whose martyrs include Pilâtre de Rozier in Calais, Madame Blanchard in Paris, Donaldson and Grimwood wrecked in Lake Michigan, Sivel, Crocè-Spinelli, Eloy, and so many others you take such care to forget!”

This was a “tac-au-tac” riposte, as they say in fencing.

“Besides,” went on Robur, “in your balloons, perfected though they may be, you could never achieve a really practical speed. You would take ten years to go around the world—which a flying machine could do in eight days!”

Fresh shouts of protest and denial, which lasted three long minutes, up to the moment when Phil Evans could take the floor.

“Mr. Aviator,” he said, “you who taunt us with the glories of aviation, have you ever aviated?”

“Of course I have!”

“And made the conquest the air?”

“Perhaps, sir!”

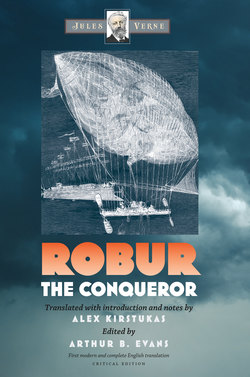

“Hurrah for Robur the Conqueror!” shouted an ironic voice.

“Why, yes! Robur the Conqueror. I accept the name, and I will use it, for I have that right!”

“We’ll allow ourselves to doubt that!” shouted Jem Cip.

“Gentlemen,” returned Robur, knitting his brow, “when I come to discuss something seriously, I do not accept denials for replies, and I would be glad to know the name of the person to whom I speak …” “I’m Jem Cip … a vegetarian …”

“Citizen Jem Cip,” replied Robur, “I’m aware that vegetarians generally have longer intestines than other men—longer by a foot at least. Which is already a good deal; so don’t force me to stretch them even further, beginning with your ears …”

“To the door!”

“To the street!”

“Dismember him!”

“Lynch law!”

“Twist him into a propeller!”

The balloonians’ fury had reached its limit. They had risen from their seats. They surrounded the platform. Robur disappeared amid a shower of arms that buffeted him like the wind of a tempest. In vain the steam whistle sent out volleys of fanfares over the assembly! That evening, Philadelphia must have imagined that fire was devouring one of its districts, and that all the water in the Schuylkill River could not put it out.

“You aren’t Americans.”

Suddenly, a movement of recoil shook through the tumult. Robur, pulling his hands out of his pockets, extended them toward the first ranks of the mob.

Slipped upon these hands were a pair of brass knuckles, which also served as revolvers and could be fired off by pressure from the fingers—in fact, little pocket machine guns.7

And then, taking advantage not only of his assailants’ recoil, but also of the silence that accompanied it:

“Decidedly,” he said, “it wasn’t Amerigo Vespucci who discovered the New World, it was Sebastian Cabot! You aren’t Americans, citizen balloonians! You’re only cabbageheads!”8

At that moment, four or five gunshots rang into the void. They hit nobody. The engineer disappeared amid the smoke, and when it had cleared, no trace of him was found. Robur the Conqueror had taken flight, just as if some flying machine had carried him off into the sky.