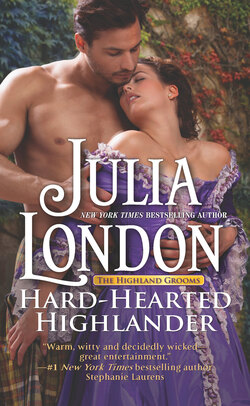

Читать книгу Hard-Hearted Highlander - Julia London - Страница 12

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

HE FIRST NOTICES her at the Mackenzie feill, an annual rite of celebration where Mackenzies and friends come from far and wide for games, dancing and song. She is wearing an arasaid plaid that leaves her ankles bare, and a stiom, the ribbon around her head that denotes she is not married. She is dancing with her friends, holding her skirt out and turning this way and that, kicking her heels and rising up on her toes and down again. She is laughing, her expression one of pure joy, and Rabbie feels a tiny tug in his heart that he’s never felt before. The lass intrigues him.

He moves, wanting to be closer. He catches her eye, and she smiles prettily at him, and that alone compels him to walk up to her and offer his hand.

She looks at his hand, then at him. “Do you mean to dance, then?”

He nods, curiously incapable of speech in that moment. Her soft brown eyes mesmerize him, make him think of the color of the hills in the morning light.

“Then you must ask, Mackenzie,” she teases him.

“W-will you dance, then?”

She laughs at his stammering and slips her hand into his. “Aye, lad. I will.”

They dance...all night. And for the first time in his twenty-seven years, Rabbie thinks seriously of marriage.

* * *

RABBIE’S MOTHER PUT her foot down with him, as if he was a lad instead of a man in his thirty-fifth year. As if he was still swaddled. “You will go and pay her a call,” she said firmly, her eyes blazing with irritation.

“She will no’ care if I call or no’,” he said dismissively.

“I care,” she snapped. “That you are not attached to her, that you do not care for her, is no excuse for poor manners. She is your fiancée now and you will treat her with the respect she is due.”

Rabbie laughed at that. “What respect is she due, Maither? She is seventeen, scarcely out of the nursery. She is a Sassenach.” She was pale and docile and hadn’t lived, not like he had. She had no experience beyond her own English parlor. She trembled when he was near—or when anyone was near, for that matter. He couldn’t imagine what he would even say to the lass, much less how he might inhabit the same house as her.

His mother sighed wearily at his pessimism. She sat next to him on the settee, where Rabbie had dropped like a naughty child when he’d been summoned. She put her hand on his knee and said, “My darling son, I’m so very sorry about Seona—”

Rabbie instantly vaulted to his feet. “Donna say her name.”

“I will say it. She’s gone, Rabbie. You can’t live your life waiting for a ghost.”

He shot his mother a warning look. “You think I wait for Seona to appear by sorcery? I saw her house. I saw where blood had spilled, where fires had burned,” he said, his gut clenching at the mere mention of it. “I’m no’ a dull man—I understand what happened. I’m no’ waiting for a ghost.” He strode to the window to avoid his mother’s gaze and to bite down his anger.

In his mind’s eye, he could see the house where Seona had lived with her family and a father who had abetted the Jacobites. A father who had sent his sons to join the forces marching to England to restore Charlie Stuart to the throne. They’d been slaughtered on the field at Culloden, and her father was hanged from an old tree on the shores of Lochcarron, so that any Highlander gliding past on a boat could see him, could see what vengeance the English had wrought on those who took Prince Charlie’s cause.

But Seona? Her sister, her mother? No one knew what had become of them. Their home had been ransacked, the servants gone, the livestock stolen or shot. There was no one left, no one who could say what had happened to them. The only ones to survive the carnage were Seona’s niece and nephew; two wee bairns who’d been sent to stay with a clan member when the news came the English were sweeping through the Highlands. There was no one else, no other MacBee living in these hills any longer. And judging by the devastation done to the MacBee home, a man could only imagine the worst—every night, in his dreams, he imagined it.

“If you’re not waiting for a ghost, then what are you waiting for?” his mother persisted as Rabbie tried once again to erase the image of the forsaken household.

Death. Every day, he waited for it. Perhaps in death he’d know what had become of the woman he’d loved. In death, there would be relief from this useless life he was living. From the searing guilt he bore every single day for having been unable to save her.

“And while you wait for whatever it is that will ease you, that poor English girl has been bartered like a fine ewe and has come all this way to a strange land, to marry a man she scarcely knows. A man who is older than her by more than fifteen years, and who is bigger than her in every way. Of course she is frightened. The least you might do is put her at ease.”

Rabbie slowly turned, fixing his gaze on his mother. “You are verra protective of a lass you scarcely know, are you no’?”

His mother’s vexation was apparent in the dip of her brows. “I was that lass once, Rabbie Mackenzie. I was a sheep, just like her, bartered to your father. I know what she must be enduring just now, and I have compassion for her. Just as I have compassion for you, darling—this isn’t what either of you hoped for, but it is what has come. If only you could find some compassion in your own heart for her, you might find a way to accept it.”

Rabbie didn’t know how to explain to his mother that words like compassion and hope were far beyond his capacity to fathom. He was merely existing, moving from one day to the next, contemplating his own death with alarming regularity.

His mother was accustomed to his surliness, however, and she didn’t wait for his answer, but turned and walked out the door of her sitting room, pausing just at the threshold. “Catriona will accompany you.”

“Cat!”

“Yes, Cat,” she said. “Your sister will be helpful in making Miss Kent feel comfortable and soothing any ruffled feathers.”

“Ruffled feathers,” he scoffed.

“Yes, Rabbie. Ruffled feathers. You have treated Miss Kent very ill.”

Rabbie shook his head.

“She’s a sweet girl. If you allowed yourself to stop thinking of your own hurts, you might be pleasantly surprised by her.”

Once again, his mother didn’t wait for him to say curtly that he couldn’t possibly be surprised by the likes of her, and quit the room.

Rabbie turned back to the window and stared blankly ahead. His mother’s words floated somewhere above him. His mind saw nothing but darkness.

* * *

WHEN RABBIE EMERGED in the bailey, having prepared himself as best he could to call on his fiancée, Catriona was already there, waiting impatiently for him. She was dressed properly, which was to say like a Sassenach. Highlanders were now banned by law from wearing plaid. His father had taken that edict to mean they should dress as the English would dress in all things. His father had softened with age, an old man with a bad leg who wanted no trouble from the redcoats that appeared from time to time at their door.

Catriona had a jaunty hat on her head, with a feather that shot off one side like an arrow’s quill. It was a hat that their sister-in-law, Daisy, had given Catriona when she and Cailean had come to Balhaire after brokering the marriage offer between the Mackenzies and the Kents.

Rabbie paused next to her mount and looked up at her hat. “That is ridiculous.”

“How verra kind,” she said saucily. “Should I inquire as to what has made you so bloody cross today, then?”

“The same that makes me cross every day—life,” he said, and hauled himself up onto the back of his horse. He gave his sister a sidelong glance. “I didna mean to wound your tender feelings,” he said, gesturing to her hat. “You know verra well what I meant by it, aye?”

“No, Rabbie, I donna know what you meant. I never know what you mean. No one knows what you mean anymore.” She was the second woman today to want no more words from him.

She wheeled her horse about and spurred it on, but then immediately drew up as two riders came in through the bailey gates. Seated behind each rider was a child.

“Who is it?” Rabbie asked as the riders turned to the right.

“You donna recognize them, then?” Catriona asked. Rabbie shook his head. “That is Fiona and Ualan MacLeod.”

The names were familiar to Rabbie, but it took him a moment to recall the children of Seona’s sister, Gavina MacBee MacLeod. The last he’d seen them they were bairns, Fiona having only learned to walk, and Ualan still toddling about on fat wee legs.

“Why are they here, then? Are they no’ in the care of a relative?”

Catriona looked at him. “Aye, the elderly cousin of a MacBee, I think. She’s passed.”

Rabbie’s gaze followed the riders with the children as they disappeared into the stables. “Who has them now?”

“No one,” Catriona said. “There are no MacBees or MacLeods left in these hills, are there? Aye, they’ve brought them to Balhaire for safe harbor until someone decides what’s to be done with them.”

Rabbie jerked his gaze to his sister. “Why was I no’ told of it?”

Catriona snorted. “Look at you, lad. Do you think any of us would add to your burden?” She sent her horse to a trot.

Rabbie looked back to where the riders had gone, but there was no sign of them. He reluctantly followed after Catriona.

The ride to Killeaven was quicker than by coach, which plodded along on old, seldom-used roads. Catriona and Rabbie rode through the forest on trails well known to them from having spent their childhood exploring the land around them. They splashed across a shallow river, then trotted up a glen, through a meadow. At the old Na Cùileagan cairn, they turned west and cantered across the open field where the Killeaven cattle and sheep had once grazed—but they were all gone, seized by the English and sold at market.

As they trotted into the drive—newly graveled—Rabbie noted the new windows and the repair to two chimneys. The weathered front door of the house swung open. Lord Kent, in the company of Lord Ramsey, strode out to greet them. Both men were dressed for riding. Behind them was Niall MacDonald. Slight and taciturn, he’d proven himself to be a keen observer. He was good at what he did for the Mackenzies—which consisted primarily of keeping his eyes and ears open and reporting back to the laird.

“There you are, Mackenzie,” Kent said. “I’d expected you well before now.”

His voice was slightly admonishing, and Rabbie resisted the urge to shrug. Not that Kent would have noticed—his gaze was on Catriona.

“I beg your pardon, we’ve been detained,” Rabbie lied. He swung off his horse to help down Catriona, but she’d leaped off her mount before he could reach her. “May I introduce my sister, Miss Catriona Mackenzie,” Rabbie said. “She was away when you arrived.”

“Miss Mackenzie,” Lord Kent said, bowing his head, and then introducing his brother. “Now then, Mackenzie. We would like to be about the business of stocking sheep here. We’ll need a market.”

“Glasgow,” Rabbie said instantly.

Kent frowned. “Glasgow is too far, isn’t it? I’d need drovers and such. I had in mind buying from Highlanders, such as yourself.”

Rabbie’s pulse quickened a beat or two. Kent thought he might help himself to what sheep they’d managed to keep, did he? “Our flocks have been decimated,” he said as evenly as he could. “Sheep and cattle alike.”

“We will eventually want to add cattle, naturally,” Kent said, as if Rabbie hadn’t spoken. If he understood how the Highland herds had been decimated, he was either unconcerned or obtuse. “But for now, we want to be about the business of sheep.”

Of course they did. Wool was a lucrative business.

“You have sheep there at Balhaire, do you not?” he asked, squinting curiously, as if he’d expected Rabbie to offer them up.

He might have said something foolish, but Catriona slipped her hand into the crook of his elbow and smiled sweetly at him. Her eyes, however, were full of warning. “Aye,” Rabbie said slowly. “But none for sale. They’ll be lambing soon.” That was a lie, but he gambled that Kent didn’t know one end of a sheep from the other.

“Well. Perhaps we’ll have a word with your father,” he said, exchanging a look with his brother. “We’re on our way to Balhaire now, as it happens.”

Rabbie could well imagine his father selling off half their flock so as not to “make trouble,” and said quickly, “You ought to call on the Buchanans” as casually as he might as he removed his gloves. “They’ve a flock they might cull.”

Behind Kent, Rabbie noticed the look of surprise on Niall’s face.

“The Buchanans,” Lord Kent repeated, sounding uncertain.

“Aye, the Buchanans. You’ll find them at Marraig, near the sea. Follow the road west. Mr. MacDonald knows where.”

Lord Kent looked back at his escort, whose expression had fallen back into stoicism, then at Rabbie. “How far?”

“Seven miles at most.”

“We’ll be met with hospitality, or a gun?”

Rabbie smiled. “This is the Highlands, my lord.” He let that statement linger, let Kent imagine what he would for a moment or two, and indeed, he and his brother exchanged another brief, but wary, look. “Aye, you’ll be met with hospitality, you will. But were I you, I’d have a man or two with me.”

Lord Kent nodded and gestured to his brother. “Assemble some of the men, then.”

He turned back to Rabbie. “Very well, we will call on the Buchanans. You’ll find your fiancée with the women.” He began striding for the stables, his business with Rabbie done.

Rabbie watched him go, trailed by his brother. Niall paused briefly before following them.

“Anything?” Rabbie asked in Gaelic.

“Only that the food is not to their liking,” Niall responded in kind.

“They’ll like it well enough, come winter,” Catriona said as she passed both men on her way to the door.

“The Buchanan sheep suffered the ovine plague,” Niall reminded Rabbie.

Rabbie gave Niall the closest thing to a smile he’d managed in weeks. “Aye, lad, that I know.”

“They’ve come round, they have,” Niall said.

“Who?”

“The Buchanans. I’ve seen them twice up on the hill behind Killeaven.”

“Aye, any clans remaining will come to have a look, will they no’?”

Niall shrugged. “It was odd, it was. They sit there, watching.”

There was no trust between the Buchanans and the Mackenzies. Rabbie couldn’t guess what they were about, but he’d reckon their interest wasn’t a neighborly one.

By the time he caught up to Catriona, the butler had already met her. The man wore a freshly powdered wig and his shoes had been polished to a very high sheen. Perhaps he thought the king meant to call today.

“Welcome,” the butler said, and showed them into the salon just beyond the entry. It smelled rather dank, Rabbie thought, even though the windows were open. Dry rot, he presumed, and supposed that would be his burden once he took the wee bird to wife.

“Have you a calling card I might present to her ladyship?” the butler asked.

Rabbie glared at him. A calling card? The lass was fortunate he’d come at all.

“I beg your pardon, but we donna make use of calling cards here,” Catriona said. “If you would be so kind, then, to tell her that Mr. Rabbie Mackenzie and Miss Catriona Mackenzie have come?”

“He knows who we are,” Rabbie said gruffly.

“Yes, of course,” the man said, ignoring Rabbie entirely as he hurried off in little staccato steps.

“A calling card,” Rabbie muttered.

“They’re English, then,” Catriona said. “They have their ways, and we have ours, aye? Donna be so sour, Rabbie.”

He might have argued with her, but they were both startled by a lot of clomping overhead and looked to the ceiling. It sounded as if a herd of cattle had been aroused. One of them—the calf, he presumed—ran from one end of the room to the other, and back again.

Moments later, they arrived in a threesome—Lady Kent and her lookalike daughter, and the maid, who barely spared him a glance as she entered, but then smiled prettily at Catriona before moving briskly to stand on the other side of the room apart from the rest.

Rabbie watched her, frowning. What made this woman so arrogant? She should have curtsied to him, as he was her superior in every way. He was so distracted by her conceit that he failed to introduce his sister or greet his fiancée.

“My brother has forgotten his manners, aye?” Catriona said. “I am his sister, Catriona Mackenzie. I was away when you arrived, tending to our aunt. She’s rather ill.”

“Oh. I am very sorry to hear it,” Miss Kent said. “Umm...” She glanced across the room at the maid, who gave her a tiny, almost imperceptible nod. “May I introduce my mother, Lady Kent?”

Lady Kent curtsied and mumbled something unintelligible to Rabbie. Catriona returned the greeting quite loudly, as if she thought the woman was deaf. Then Miss Kent slid her palms down her side and said, “Good afternoon, Mr. Mackenzie” without looking directly at him.

“Aye, good afternoon.”

“Will you please sit?” she asked.

“Thank you,” Catriona said, and plunked herself down on a settee. Rabbie didn’t move from his position near the hearth.

“Might I offer you something to drink?” Miss Kent asked in a manner that suggested she’d been rehearsing the question, and looked nervously to Rabbie.

“No. Thank you.”

“Have you any ale?” Catriona asked. “I’m a wee bit dry after our ride.”

Miss Kent looked startled by Catriona’s request. “Ah...” She glanced to the butler, who nodded and walked out in that same eager manner as before.

The maid was now leaning against a sill at the open window, gazing out, as if there was no one else in the room but her. “Oh, I beg your pardon, sir,” Miss Kent said, having noticed the direction of Rabbie’s gaze. “M-may I introduce Miss Bernadette Holly? She is my lady’s maid.”

Miss Bernadette Holly pushed herself away from the sill and sank into what could only be termed a very lazy curtsy.

“Aye, we’ve met,” he said dismissively.

“You have?” Miss Kent exclaimed.

“In the Balhaire kitchen,” he said, at the very same moment the maid said, “No.”

Miss Kent looked at her lady’s maid, her brows rising higher.

“What I mean to say is that we were not formally introduced,” Miss Holly said. “Our paths crossed in the kitchen, that’s all.”

One of Rabbie’s brows rose above the other. Was she openly contradicting him, this lady’s maid?

“Oh, dear, of course, the kitchen,” Miss Kent said. “That was...well, it was an unfortunate oversight.”

He didn’t know what Miss Kent thought was an oversight and he didn’t care. He kept staring at the maid, this Miss Holly, wondering how she kept her employ with her supercilious ways. She leaned against the sill once more and folded her arms across her body, returning his gaze with one that seemed almost impatient.

“Do you ride, Miss Kent?” Catriona suddenly interjected, heading off anything Rabbie might have said about the maid.

“Oh, I, ah... I am a poor rider,” the bird said, and glanced uncertainly at Miss Bernadette Holly, who once again gave her an almost imperceptible nod, as if giving her permission to continue. Rabbie glared at her.

“There is much to see in these hills, views you’d no’ see in England, aye? Perhaps you would join Rabbie and I one afternoon?” Catriona suggested.

Again, Miss Kent looked to Miss Holly. This time, she raised her dark brows, and Miss Kent spoke instantly. “Yes, thank you.”

What was this, was the bird the maid’s bloody puppet? Even the girl’s utterly useless mother kept glancing nervously and fretfully at Miss Holly.

Miss Holly smiled a little at Miss Kent, and Miss Kent suddenly smiled, too, as if she’d just remembered an amusing jest. And then she blushed, as if she were embarrassed by the jest. Diah, she was more a child than a woman grown. Rabbie shifted restlessly and caught Catriona’s eye. She gave him a very meaningful and slightly heated look.

He suppressed a sigh of tedium and looked at the bird again. The color in her cheeks was very high.

The butler returned with Catriona’s ale, at which point Miss Kent took a seat beside Catriona.

“How do you find Killeaven?” Rabbie asked, making some effort, he thought, although his voice was flat and emotionless, no doubt because he didn’t care what she thought of Killeaven.

“It’s...well, it’s bigger than I anticipated,” Miss Kent said, and again looked to Miss Holly. “I suppose...that is to say, perhaps we might make improvements to it?”

Was she asking him? “Pardon?”

Miss Kent looked in his direction—but at his feet. “Perhaps we might make some improvements to the house and the grounds.”

He didn’t care what she did to Killeaven. Burn it down for all he cared. “I donna really care.”

That earned him another heated look from his sister. “What my brother means is that it is up to you, Miss Kent. This is your house to do as you please, aye?”

He hadn’t meant that at all.

“Would you like to see it?” Miss Kent asked suddenly. She was not speaking to Rabbie, but to Catriona.

Catriona gulped down a bit of ale and said, “I should like it verra much, I would.” She stood.

Miss Kent and her mother rose almost as one. The three of them walked out of the room, Miss Kent suddenly jabbering. At the door, Catriona glanced back and motioned with her head for Rabbie to come along. He ignored her. He didn’t care about this house. What he cared about was Catriona’s unfinished ale. He walked to the settee and the small table where she’d set it down, picked it up and drained it. He put the empty glass down, folded his arms and turned to Miss Holly.

She was glaring at him.

“Aye, what, then?” he asked impatiently. She shook her head, as if the burden of explaining what, exactly, was too great. “You are a peculiar one,” Rabbie said irritably.

She watched him in silence.

“Tell me, then, is your charge capable of rational thought? Or must you do all of it for her?”

“I beg your pardon,” she said indignantly. “I don’t do any thinking for her.”

“No? Why, then, does she look to you before she answers any question put to her?”

“She is anxious,” Miss Holly said instantly. “And eager to impress you.”

He snorted. “Well, that’s no’ possible.”

“Is it likewise not possible for you to make her feel the least bit welcome?”

He jerked his head up at that bit of insolence. “You dare to instruct me, lass?” he asked incredulously.

“Someone ought to,” she said pertly.

In that moment, Rabbie felt something besides anger or despair—he felt stunned. He’d never in his life been addressed by a servant in such a manner. He didn’t know what game she was playing with him, but it was an unwinnable one. He casually moved to where she stood, standing close, towering over her. She was pretty in an exotic way, he decided. Her skin was flawless. Her lips were full and the color of new plums. And her brows, dark and full, were dipped into an annoying vee shape above those pretty hazel eyes sparkling with ire. “A wee bit of advice, lass,” he said, voice low as he took in the slight upturn of her nose and the strand of hair that had come undone and now draped across her smooth, creamy décolletage. “Donna think to shame me. It will no’ work. For one, I donna care what that wee mouse thinks of me, aye? For another, there is little anyone can do to me that’s no’ already been done, and been done worse.”

One her dark brows lifted in a manner that reminded him of a woman hearing a tale she did not believe.

“You donna care for me, then,” he allowed. “I donna care for you, either. But I will marry that lass, and if you continue on as you have in my presence, I will put you out on your lovely arse and pack you back to bloody old England. Do you understand me?” He was confident that would do it—that would make her quake in her festive little slippers.

But the maid surprised him with a smirk; she seemed almost amused by his threat. “Neither should you think to threaten me, sir. For there is little you can do to me that has not already been done, and been done worse.” She gave him a bit of a triumphant look and stepped around him, walking out of the room and leaving the faint scent of her perfume in her wake.

What did that mean? What might have possibly been done to that privileged little butterfly? She was naive—she had no notion of the cruelty of life, not like he did.

But her lack of fear and her conceit would not leave him. He was still brooding about it when the women returned, at which point he picked up his gloves and held out his arm to Catriona. “We’ll take our leave, aye? Lady Kent, Miss Kent, you and your family are invited to dine at Balhaire this Friday evening if it suits,” he said formally.

The mouse smiled with surprise.

“Your lady’s maid as well,” he added awkwardly and, at least to him, surprisingly.

The mouse smiled as if she hadn’t a brain in her head.

“We might discuss the details of the wedding, aye?” Catriona added. “Our customs are a wee bit different.”

“Oh. Yes, we should...we would like that very much, wouldn’t we, Mamma?” the mouse asked uncertainly.

“Yes, thank you,” the mother said, and returned her daughter’s anxious smile.

“Aye, verra well.” Rabbie was suddenly eager to be gone. “Cat?” He began striding for the door.

They walked out of the house, Miss Kent and Lady Kent trailing behind, calling their goodbyes and thank-yous. Rabbie mounted his horse and looked back at the house, and imagined those hazel eyes shooting daggers at him from behind one of the new windows.