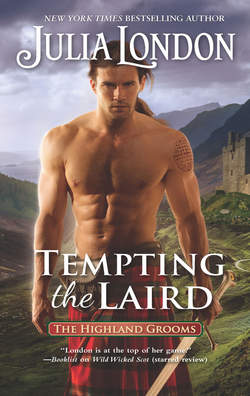

Читать книгу Tempting The Laird - Julia London, Julia London - Страница 13

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

“YOU’RE CERTAIN OF THIS, are you?” Hamlin asked.

“Aye,” Eula said. She was standing on a chair before him, working on the knot of his neckcloth, her brow furrowed in concentration.

“I was speaking to Mr. Bain,” he said, and touched the tip of his finger to her nose.

“Aye, your grace, that I am,” a voice behind Hamlin said.

Hamlin eyed the reflection of his secretary, Nichol Bain, in the mirror. He was leaning against the door frame, his arms folded across his chest, watching Eula’s ministrations. The auburn-haired, green-eyed young man was ambitious in the way of young men. He didn’t care about the rumors swirling around Hamlin, he cared about performing well, about parlaying his service to a duke to a better position. What would that be, then? Service to the king? Hamlin could only guess.

Bain had come to Hamlin through the Duke of Perth, the closest friend of his late father. As Hamlin had been a young man himself when he’d become a duke, Perth had taken him under his wing, and twelve years later, like his father before him, Hamlin considered Perth his closest adviser. Perth had brought Bain to him, had vouched for what Hamlin had thought were rather vague credentials.

Bain’s expression remained impassive as he calmly returned Hamlin’s gaze in the mirror. The man was impossible to discern. Whatever he thought about any given situation, he kept quite to himself unless asked. But he’d made up his mind about tonight’s dinner at once when Hamlin had asked. Frankly, he’d hardly thought on it at all. He’d said simply, “Aye, you must attend.”

Hamlin looked at himself in the mirror, eyeing his dress. He’d not seen about acquiring another valet since the last one had “retired” from his post after the fiasco with Glenna. He’d never been anything but perfectly civil to the man, and yet he’d believed the talk swirling around his master. Fortunately, Hamlin was quite capable of dressing himself and had donned formal attire. His waistcoat was made of silver silk, his coat and breeches black. Alas, Eula’s attempt to tie his white silk neckcloth had not met with success.

“I think it a waste of time,” he said to his reflection, returning to his conversation with Bain. “Nothing of consequence can come of it.”

“It is well-known that the Earl of Caithness is unduly influenced by MacLaren’s opinion. A vote from Caithness will be instrumental, if no’ decisive,” Bain said. “It could verra well be the vote to put you in the Lords, aye? The more familiar you are with the Caithness surrogate, the better your odds.”

Hamlin responded with a grunt. If he secured a seat in the House of Lords, it would be nothing short of a small miracle. Scotland was allowed sixteen seats, and those seats were determined by a vote of the Scottish peers. Four had opened, and his name had been put forth by virtue of his title. But his appointment, which had once been seen as a fait accompli, was now tenuous at best. People did not care to be represented by a man rumored to be a murderer.

“You see this as an opportunity to be familiar with MacLaren. I see it as an opportunity for a lot of scandalmongers to invent a lot of scandal.”

“What does it mean, scandalmonger?” Eula asked.

“It means busybodies have been invited to dine, that’s what.”

She shrugged and hopped down from the chair, her task complete. “Will the lady attend?”

“What lady?” Hamlin asked absently as he tried to straighten the mess she’d made of his neckcloth.

“The bonny one with the golden hair.”

And the gray-blue eyes. He could not forget those eyes sparkling with such mischievous delight. She was a minx, that one. It seemed of late that when most women viewed him at all, it was with a mix of horrified curiosity and downright fear. But Miss Mackenzie had looked at him as if she wanted to either challenge him to a duel or invite him to dance. He didn’t know what to make of her forthright manner, really. He wondered if anyone had ever tried to bring her to heel. She was not a young debutante, that much was obvious, but a comely, assured woman, scarcely younger than he. Which raised the question of how a beautiful woman of means was not married? “I believe she will be, aye,” he said to Eula.

“I rather like her,” Eula said.

Of course she did—Eula was a wee minx herself, and with no woman to properly guide her, she was turning into a coquettish imp. “Where is your maid, then, lass? ’Tis time for your bed, I should think.”

“Already?” Eula complained.

“Already.” He leaned down and kissed the top of her head.

“You look very fine, Montrose,” she said, eyeing him closely.

“Your grace,” he reminded her.

“Your grace Montrose,” she returned with a pert smile. In the mirror’s reflection, Hamlin caught Bain’s slight smile of amusement.

“Off you go, then. I’ll come round to see you on the morrow, aye?”

“Good night,” she chirped, and skipped out, intentionally poking Bain in the belly as she passed him.

When she had gone out, Hamlin undid his neckcloth and began to tie it again. “You’re convinced, are you, that given all that has happened, I still stand a chance at gaining a seat?” Hamlin asked bluntly.

“No’ convinced, no, your grace,” Bain said. “But if anyone will consider a change of heart, ’tis MacLaren. He would keep the seat close to home and his interests rather than stand on principle.”

Apparently, Hamlin was the unprincipled choice for the seat. He mulled that over as he retied his neckcloth. He was not shocked that MacLaren might advocate for him for less than principled reasons—a seat in the Lords wielded considerable power in Scotland, and Hamlin would be expected to return favor to whomever had supported him. But he wasn’t convinced that MacLaren’s lack of principle would extend all the way to him. He could very well have another candidate in the wings.

Never mind all this dithering about the evening on his part. He’d sent his favorable reply to Norwood on Bain’s recommendation and would attend this bloody dinner. He was, if nothing else, a man of his word.

His butler appeared in the doorway and stood next to Bain. “Shall I have your mount saddled, your grace?”

It was a splendid night for riding, the moon full, the path through the forest that separated Blackthorn Hall and Dungotty pleasant and cool. But before Hamlin could answer, Bain lifted a finger. “If I may, your grace.”

Hamlin nodded.

“To arrive on horseback to an important supper such as this might give the appearance of having suffered a diminishment in your standing. I’d suggest the coach, then.”

A diminishment of standing. Is that what was said of him now? Hamlin sighed with irritation at the lengths he had to go to present himself to a society he’d once ruled and that had been quick to turn its back on him. Before he’d been married, invitations to Blackthorn Hall had been sought after throughout Scotland and even in England—the prospect of marrying a future duke, particularly one with the revered name of Montrose, had brought the lassies from far and wide. Hamlin had had no firm attachment to any of them, and he’d agreed to marry the woman his father had deemed suitable to carry the Montrose name and bear its heirs.

After his marriage, Hamlin and Glenna hosted dinners and balls for the country’s elite in his ailing father’s stead, as was expected of him, the heir. And when his father died, and the title had passed to him, Hamlin had stepped into his father’s shoes. He and Glenna had dined with peers, appeared in society when it was expected. He opened a school and presented funds to a theater troupe. He sat on councils and hunted game and joined men at the gentleman’s club in Edinburgh to complain about the government.

He had performed the duties of a duke in the same distant manner as his father had before him. Not because he was the same distant person his father had been—Hamlin liked to think himself as warmer than his father had ever been—but because he was already having trouble with Glenna and he didn’t want anyone to know.

The trouble with Glenna was not apparent to anyone else before the disaster fell that ruined his life and his spirit, and left him desolate and questioning everything he thought he’d ever known about himself or this world. What had happened at Blackthorn Hall was a disgrace to any man.

That astounding fall from grace was the reason he’d taken Nichol Bain into his employ. The first thing Bain had said to Hamlin the day they met was I am the man who might repair your reputation, I am.

Normally, Hamlin would have taken offense to that. But he was intrigued by Bain’s lack of hesitation to say it, and he was acutely aware that his reputation was in critical need of repair. This was, in fact, the first invitation he’d received in several months.

“Aye, Stuart, do as he says, then,” Hamlin conceded. “The coachmen and the team will no’ care to stand about waiting for a lot of fat Englishmen to dine, but that’s their lot in life, it is.”

* * *

THE EMBLAZONED MONTROSE coach drew to a halt in the circular drive at the Dungotty estate, and two footmen sprinted to attend it. The door was opened for Hamlin, a step put down for his convenience to exit the coach. The front door likewise opened for him before Hamlin could reach it, and a man wearing a powdered wig and a highly embroidered, fanciful coat stepped forward, bowed low and said, “Welcome to Dungotty, your grace.”

“Thank you.” He handed the man his hat as he stepped into the foyer. The grand house had had a bit of work done to it since Hamlin had last seen it, which he recalled was at least a decade ago, before his marriage. Marble flooring had replaced wooden planks, and an expansive iron-and-crystal chandelier blazed with the light of a dozen candles overhead. The stairs leading to the first floor were dressed in expensive Aubusson carpets, the railing polished cherry.

Hamlin removed his cloak, handed it to yet another footman and wondered just how many footmen an English earl actually needed for summering in Scotland. He’d seen more tonight than he had on staff at Blackthorn Hall, which was twice the size of this house.

The sound of laughter suddenly rose from a room down a long hall. Hamlin immediately tensed—it sounded as if there were more souls laughing than the four he expected, which were the MacLarens, Norwood and his niece.

“This way, if you please, your grace,” the butler said, and walked briskly in the direction of the laughter, down a corridor and to a set of double doors. He placed both hands on the brass handles, paused and gave his head a bit of a shake, then practically flung the doors open. He stepped inside and loudly cleared his throat. Standing behind him, Hamlin could see a number of heads swivel around. Damn it to hell, he’d been waylaid by that old English goat. There was a crowd gathered in this room.

The butler bowed and said quite grandly, “My Lord Norwood, may I present his grace, the Duke of Montrose.”

Hamlin moved to step forward, but the butler was not quite done.

“And the Earl of Kincardine,” he added, just as grandly.

Hamlin waited a moment to ensure that was the end of it, but as he moved his foot, the butler added with a flourish, “And the Laird of Graham.”

Well, that was definitely the end of it, as he held no other titles. But Hamlin arched a brow at the butler all the same, silently inquiring if he was done. The butler bowed deeply and stepped back.

Hamlin walked into the room and looked around at the dozen souls or more gathered. He made a curt bow with his head, and almost as one, the ladies curtsied and the men bowed their heads back at him.

“Welcome, welcome, your grace!” Norwood appeared through what felt a wee bit like a throng, one arm outstretched, the other hand clutching a glass of port. He was dressed in the finest of fabric, his waistcoat nearly to his knees and as heavily embroidered as the butler’s. They shared a tailor, it would seem.

“We are most pleased you have come. May I introduce you to my guests?” Norwood said, and gestured to the MacLarens. “Mr. and Mrs. MacLaren, with whom, I am certain, you are acquainted.”

“Your grace,” Mrs. MacLaren said, and curtsied, her powdered tower of hair tipping dangerously close to Hamlin.

“Montrose, ’tis good to see you about,” MacLaren said, eyeing Hamlin shrewdly as he gripped his hand and shook it heartily.

“Thank you,” Hamlin said.

When MacLaren had taken a good long look at him, he shifted his gaze to Norwood, and something flowed between those two men that Hamlin didn’t care for. That was precisely the reason he hadn’t wanted to come here this evening—the unwelcome scrutiny, the assumptions about what had happened at Blackthorn.

“My dear friend Countess Orlov and her cousin, Mr. Vasily Orlov,” Norwood continued, introducing him to a middle-aged woman with dark hair and rouged cheeks, and her fastidiously dressed cousin, who wore a sash across his chest with several medals pinned to it.

He was then introduced to an English family, the Wilke-Smythes, whose relation to Norwood was quite unclear. Lord Furness, a corpulent man who, from what Hamlin could glean, was an old friend. He seemed already well on his way to being thoroughly pissed. Next was Mrs. Templeton, a woman with a full bust and a painted fan, which she employed with great verve in the direction of her décolletage.

“Lastly, my dear niece Miss Mackenzie, who has already had the great pleasure of making your acquaintance,” Norwood said, and waved airily at his niece.

She had made it quite clear it was not a pleasure, as he recalled. Miss Mackenzie rose elegantly from her inelegant perch on the arm of a settee. “It was indeed a great pleasure, your grace,” she said with a wee lopsided smile that made it seem as if she was teasing him. She was wearing a shimmering gown of silver silk cut so daringly low across her bosom that standing over her, Hamlin had a most enticing view of creamy, full breasts. Her eyes, the remarkably brilliant gray-blue orbs, were shining at him a mix of mirth and curiosity. Her golden hair had been fashionably arranged on top of her head, pinned with a pair of tiny ornamental bluebirds, and a pair of long curls dangled across her collarbone.

He inclined his head. “Miss Mackenzie.”

She sank into a curtsy at the same moment she offered her hand to him. He reluctantly took it, bowing over it, touching his lips to her knuckles. It struck him as somehow incongruent that a woman with such an audacious manner should have such an elegant hand that smelled of flowers.

He lifted her up and let go of her hand.

“There, then, the introductions are done,” Norwood said. “You are in want of a whisky, your grace, are you not? I know a Scotsman such as yourself enjoys a tot of it now and again. My stock has come from my sister, Lady Mackenzie of Balhaire, and she assures me it has been distilled with the greatest care.”

“No, thank you,” Hamlin said. He would prefer to keep all his wits about him this evening.

Miss Mackenzie arched a brow. “Do you doubt the quality of our whisky, then, your grace? I’ve brought it all the way from our secret stores at Balhaire.”

“I’ve no opinion of your whisky. I donna care for it,” he said, but really, it was the whisky that didn’t agree with him. The worst argument he’d ever had with Glenna came after an evening of drinking whisky. Hamlin had sworn it off after that night. He’d never believed himself to be one who suffered the ravages of demon drink, but a bad marriage could certainly illuminate the tendency in a man.

The lass smiled and said, “There you have it, uncle—that is two of us, both Scots, who donna care for whisky.”

“What? I’ve seen you enjoy more than a sip of whisky, my darling,” the earl said, and laughed roundly.

She shrugged, still smiling.

“Will you have wine?” Norwood asked Hamlin.

“Thank you.”

“Rumpel! Where are you, Rumpel?” Norwood called, turning about and wandering off to find someone to pour a glass of wine.

His niece, however, showed herself to be more expedient. She walked to a sideboard, poured a glass of wine and returned, handing it to Hamlin.

He took it from her, eyeing her with skepticism. “Thank you.”

“’Tis my pleasure, your grace. I find that a wee bit of wine eases me in unfamiliar places. It helps loosen my tongue.” She smiled prettily.

Did she think him uneasy? She stood before him, her hands clasped at her back. She made no effort to move away or to speak. No one else approached, which didn’t surprise Hamlin in the least. He’d been a pariah for nearly a year and knew the role well.

“Will it surprise you, then, if I tell you I didna believe you’d accept our offer to dine?” she asked.

He considered that a moment. “No.”

“Well, I didna believe it. But I’m so verra glad you’ve come.”

He arched a brow with skepticism. “Why?” he said flatly.

She blinked with surprise. She gave a cheerful little laugh and leaned slightly forward to whisper, “Because, by all accounts, your grace, you’re a verra interesting man.”

That surprised him. Was she openly and, without any apparent misgivings, referencing the untoward rumors about him? “You shouldna listen to the tales told about town, Miss Mackenzie.”

“What tales?” she asked, and that mischievous smile appeared again. “What town?”

“Here we are!” Norwood said, reappearing in their midst. He’d brought the butler, who carried a silver tray on which stood a small crystal goblet of wine. Norwood spotted the wine Hamlin already held. “Oh,” he said, looking confused. “Well, never mind it, Rumpel,” he said, and waved off the glass of wine the butler was trying to present to Hamlin. “You may take that away. I beg your pardon, Montrose, if my niece has nattered on. Have you, darling?” he asked, smiling fondly at her. He probably doted on her, which would explain her impudence. She’d probably been allowed to behave however she pleased all her life.

“Whatever do you mean, uncle?” Miss Mackenzie asked laughingly.

“Only that you are passionate about many things, my love, and given opportunity, will expound with great enthusiasm.”

Miss Mackenzie was not offended—she laughed roundly. “You dare say that of me, uncle? Was it no’ you who caused your guests to retire en masse just last evening with your lengthy thoughts about the poor reverend’s most recent sermon?”

“That was an entirely different matter,” Norwood said with a sniff of indignation. “That was an important matter of theology run amok!”

“Milord.” The butler had returned, sans tray and wine. “Dinner is served.”

“Aha, very good.” Norwood stepped to the middle of the room and called for attention. “If you would, friends, make your way to the dining room. We do not promenade at Dungotty, we go in together as equals. And we dine at our leisure! I’ll not insist we race through our courses like the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, whom I know firsthand to be quite rigid in her rules for dining. Countess Orlov has been so good as to help me determine the places for everyone. You will find a name card at each setting. Catriona, darling, will you see the duke in, please?” With that he turned about and offered his arm to the young Miss Wilke-Smythe.

Miss Mackenzie held her hand aloft in midair. “You heard my uncle—I’m to do the escorting of our esteemed visitor, who, it would seem, is no’ our equal after all, but above us mortals and worthy of a special escort.”

The woman was as impudent as Eula.

She smiled slyly at his hesitation. “Please donna give him reason to scold me.”

With an inward sigh, Hamlin put his hand under her arm and promenaded her into the dining room ahead of everyone but Norwood.

The dining room was painted in gold leaf and decorated with an array of portraits of men and women alike. The table had been set with fine china, sparkling crystal, and silver utensils and candelabras polished to such sheen that a man could examine his face in them. A floral arrangement of peonies graced the middle of the table, and as Hamlin took his seat, he discovered that one had to bend either to the left or right to see around the showy flowers.

On his right was the Wilke-Smythe miss, and on his left, Mrs. MacLaren. He was not entirely sure who sat across from him, given the flowers. Norwood was seated at the head of the table, naturally, and anchoring the other end was Miss Mackenzie. She had the undivided attention of Mr. Orlov to her right, and Lord Furness to her left.

The dinner began with carrot soup, progressed to beef, potatoes and boiled apples, and was, Hamlin would be the first to admit, quite well-done. The earl had not exaggerated his cook’s abilities.

In the course of the meal, Mrs. MacLaren asked after Hamlin’s crops. Yes, he said, his oats were faring well in spite of the drought this summer. Yes, his sheep were grazing very well indeed.

When he turned his attention to his right, Miss Wilke-Smythe was eager to speak of the fine weather, and how she longed for a ball to be held this summer at Dungotty. “I miss England so,” she said with a sigh. “I’m invited to all the summer balls in England. On some nights, I keep a coach waiting so that I might go from one to the next.”

She made it sound as if there were scores of summer balls, dozens to be attended each week. Perhaps there were. He’d not been to England in years.

“Alas, there are none planned for Dungotty,” she said, pouting prettily, and Hamlin supposed that he was supposed to lament this sad fact, and on her behalf, either make a plea to her host to host one or offer to arrange one himself. But Hamlin couldn’t possibly care less if there were a hundred balls planned for Dungotty this summer, or none at all.

His lack of a response seemed to displease Miss Wilke-Smythe, for she suddenly leaned forward to see around him. “My Lord Norwood, why are there no balls to be held at Dungotty this summer?”

“Pardon?” the earl asked, startled out of his conversation with Countess Orlov. “A ball? My dear, there are not enough people in all the Trossachs to make a proper ball.”

This answer displeased Miss Wilke-Smythe even more, and she sat back with a slight huff. But then she turned her attention to Norwood’s niece. “Do you not agree, Miss Mackenzie, that we are in need of proper diversion this summer?”

Miss Mackenzie was engaged in a lively conversation with Mr. Orlov and looked up, her eyes dancing around the table as if she was uncertain what she might have missed. Her cheeks were stained a delightful shade of pink from laughing, and her eyes, even at this distance, sparked. “I beg your pardon?”

“I was just saying that Dungotty is so very lovely,” Miss Wilke-Smythe explained, “but there are very few diversions. How shall we ever survive the summer without a ball?”

“Oh, I should think verra well,” Miss Mackenzie said. “We survive them without balls all the time, do we no’, Mrs. MacLaren? I intend to survive the summer by returning home,” she said. “You must all take my word that the journey to Balhaire is diverting enough for a dozen summers.”

Her announcement caused Miss Wilke-Smythe more distress. “What?” she cried, sitting up, her fingers grasping the edge of the table. “You mean to leave us? But...but when? How long will we have your company at Dungotty?”

This outburst had gained the attention of everyone at the table, and they all turned to Miss Mackenzie, awaiting her answer.

“A fortnight,” she said. She smiled and turned her attention back to the Russian, apparently intent on continuing her conversation, but Miss Wilke-Smythe pressed on.

“But why must you go?”

“Yes, why indeed?” Mr. Orlov seconded as his hand strayed near Miss Mackenzie’s, his fingers touching her thumb. “You do not mean to deprive us of your lovely company, surely. You must stay the summer, Miss Mackenzie, for I shall be highly offended if you do not.”

Miss Mackenzie laughed. “You might be offended for all of an afternoon, sir, but I’ve no doubt you’d find suitable company, aye?”

“Oh, she means to stay,” Norwood said dismissively. “She’s been too long in the Highlands.”

“Too long in the Highlands, as if that were possible!” Miss Mackenzie playfully protested. “You know verra well that I’ve an abbey to attend to, you do, Uncle Knox. I intend to leave in a fortnight.”

“An abbey!” Mrs. Templeton said, and snorted. “I would not have guessed you a nun.”

Miss Mackenzie did not take offense to that purposeful slight. She laughed again, delighted by the remark. “On my word, I’ve no’ been accused of being a nun, Mrs. Templeton. But I’ve wards that need looking after, aye?”

“You’re far too young for wards, Miss Mackenzie,” Mrs. Wilke-Smythe said graciously.

“She is indeed, but she speaks true,” Norwood says. “My niece and her dearly departed lady aunt have provided shelter for women and children for a few years now.”

Shelter for women and children? Wards? Hamlin looked curiously at Miss Mackenzie. He himself had a ward. That she had a ward—several of them, by the sound of it—aroused his curiosity.

She looked around the table at everyone’s sudden attention to her. Her laugh was suddenly self-conscious. “Why do you all look at me this way, then? Have you never done a charitable thing, any of you?”

“’Tis more than charity, my darling,” Norwood said.

“What women?” Mrs. Templeton demanded. “What children?”

“Women who’ve no other place to go, aye?” Miss Mackenzie explained. “They’ve taken up rooms at an abandoned abbey on property my family owns, that they have.”

“Why have they no place to go?” Miss Wilke-Smythe asked with all the naivete of her age.

“That’s...that’s no’ an easy answer, no,” Miss Mackenzie said, and shifted uncomfortably. For the first time since Hamlin had made her acquaintance, she seemed at a loss for words and looked to her uncle for help. “It’s that they are no’ welcome in society or with families for...for various reasons.”

“Good Lord,” Furness said. “Do you mean—”

“Aye, I mean precisely that, milord,” she said quickly before he could say aloud who these women were. “Women who have been cast out, along with their children.”

That was met with utter silence for a long moment. Mrs. Wilke-Smythe looked at her husband, but he was staring at Miss Mackenzie.

Privately, Hamlin marveled at her revelation. The sort of charitable work she was suggesting she did was the kind generally reserved for Samaritans and leaders of the kirk. Ladies of Miss Mackenzie’s social standing might embroider a pillow or collect alms, but they did not generally participate in a manner that would put them into direct contact with such outcasts. Or at least, they would not house them. It appeared that Miss Mackenzie was more than a pampered woman of privilege.

“What do you make of it, Montrose?” MacLaren abruptly asked him. “Seems the sort of thing you’d run across now and again in the Lords, does it no’? Social injuries, poor morals and the like?”

“They donna have poor morals,” Miss Mackenzie said, her voice noticeably cooler. “Or if they have poor morals, it is because the poor morals were forced onto them.”

MacLaren ignored her, his gaze on Hamlin. “Well? What would you say to someone with Miss Mackenzie’s passion for the depraved?”

“They are no’ depraved!” she said, her voice rising.

“Yes, your grace, what do you say to it?” the countess asked him.

One reason Hamlin was intent on gaining a seat in the House of Lords was to address social injustice, to move Scotland forward, away from the rebellions of the past. Change was needed. Many people had been displaced by the rebellion, he knew, but even he was taken aback by this. Women and children living in a run-down abbey? He glanced at Miss Mackenzie, who was watching him without any discernible expectation. He realized she didn’t care what he thought of it. That also intrigued him. “One canna dictate or impose on the charitable intentions of another, aye?”

“One can if it’s wrong,” MacLaren said.

Miss Mackenzie’s gaze narrowed slightly, and she looked away.

“For God’s sake, Rumpel, take that arrangement away, will you?” Norwood complained. “I can’t see Cat from here.”

The butler moved at once to remove the offending peonies.

“Catriona is a philanthropist,” Norwood continued, looking around at them all.

“Philanthropy!” Countess Orlov suddenly laughed. “Of course, that explains it! I understood something much different, but now I understand it plainly. The Orlov family is among the greatest philanthropists of Russia.”

Miss Mackenzie’s face had turned a subtle shade of pink. “’Tis no’ philanthropy,” she said low. “My family is verra generous with their resources, aye, but ’tis a wee bit different for me. I verra much want to help them. By the saints, I donna understand anyone who’d no’ want to help them. Their lives have unfurled in ways through no fault of theirs, and life can be verra cruel to women, it can.”

“Oh, dear,” Mrs. MacLaren muttered despairingly. “Do you mean that life has been cruel to you, then?”

“To me?” Miss Mackenzie clucked her tongue. “No’ to me. I’ve had every privilege. But to women born to less fortunate circumstances, aye? Women without a family fortune to gird them, aye? I’ve wanted for nothing in my life, no’ a thing. But these women? They’ve wanted for compassion and love, a place to call their own. They’ve wanted food for their children and shoes for their feet. Some of them have come with hay stuffed into their shoes to keep the damp from seeping in. Can you imagine it, any of you?”

It was the height of indelicacy to speak of these things at a supper table, but Hamlin found her response to be intriguing and, frankly, righteous. Everyone needed to understand the inequalities that existed in their world.

“I wouldn’t know about that, but life has certainly been cruel to me,” Mrs. Templeton said bitterly, prompting Norwood to pat her kindly on the hand before she swiped up her wineglass and drank. Mrs. Templeton seemed to have forgotten she was dressed in silk and dripping in jewels. She clearly didn’t understand what cruel meant.

“What madness is this?” Furness demanded of Norwood. “How is it your family has allowed one of your own to...to consort with such women and in such a public manner?”

“I beg your pardon, sir, but my uncle doesna speak for me,” Miss Mackenzie said calmly, although the color was high in her fair cheeks, and her grip of the table so tight that Hamlin could see the whites of her knuckles from where he sat. “Griselda Mackenzie, God rest her soul, turned an old abbey into a safe haven for the forlorn and the lost, aye? I donna know all the circumstances that brought these women to Kishorn, but it never mattered to her, it did no’—what mattered was that they’d lost their husbands and fathers and brothers, with no one to provide for them, or had escaped situations in which their bodies were used for the pleasure of men.”

Mrs. Wilke-Smythe gasped with alarm. Her daughter’s eyes rounded.

“None of them had a place to go, no’ until Zelda revived the old abbey for them.”

“But that’s...that’s hardly proper,” Mrs. Wilke-Smythe said uncertainly.

“Neither is it proper to leave them in the cold with no hope,” Miss Mackenzie retorted.

“But what do you do?” Miss Wilke-Smythe asked, clearly enthralled by this unexpected side of Miss Mackenzie, while her mother withered in her seat, clearly undone by the world beyond ivy-covered walls. “Do you mean you are with them?”

Miss Mackenzie let go her grip of the table and touched a curl at her neck. “Aye, I am. I see after them, that’s what,” she said with a shrug. “I see that they have all they need.”

“My niece is to be commended,” Norwood said firmly, but it was clear to Hamlin that few others in this room, with perhaps the exception of Vasily Orlov, shared his view. “Frankly, it is unconscionable that there are those who would cast out these women and children from the safety of an old abbey when they can’t properly fend for themselves,” he continued.

“Who would cast them out?” asked MacLaren.

“Highland lairds,” Miss Mackenzie said. “They donna like them so close, aye? They can find no pity in their hearts, can see no value in them. They view them as hardly better than cattle.”

“How do you presume to know what is in the hearts of the lairds?” Lord Furness demanded.

“Englishmen, too,” she continued, ignoring him. “They want the land for their sheep. They mean to seize the property. The Crown has determined it forfeit.”

“On what grounds?” MacLaren asked gruffly.

“I’ll tell you the grounds,” Norwood said grandly. “My niece will not tell you the whole story, I’m certain of it. Her aunt, who I may personally attest was as daring a woman as I’ve ever known, and if I might say so, quite beautiful,” he added wistfully, “in her own way assisted the Jacobite rebels who fought to overthrow our king by hiding them when they fled to escape the English forces.”

There were gasps all around, which Norwood clearly relished.

“Treason!” MacLaren uttered.

“Uncle, perhaps you ought no’—”

“Perhaps they ought to know the truth, darling.”

Hamlin’s curiosity about this abbey was entirely kindled. He had not been on the side of the Jacobites—he was loyal to the king. But like most Scots, he was not particularly fond of the English and their ways.

“This woman’s aunt was a traitor to the king and the Crown,” Furness said angrily, pointing at Miss Mackenzie.

“Furness, for God’s sake, man, she was a benevolent,” Norwood said impatiently. “When the rebellion was put down, and these men faced certain death, she took it upon herself to help them escape with their lives instead of seeing them slaughtered. Find fault with it if you will, but I think it a very noble thing to do for one’s countrymen.”

No one argued with Norwood’s impassioned defense, but Hamlin privately wondered if it was truly noble to aid traitors, no matter if they were countrymen.

“Shall I tell you what else?” Norwood asked, leaning forward now, one elbow on the table.

“No, Uncle Knox,” Miss Mackenzie said, sounding slightly frantic.

But Norwood had the room’s rapt attention, and Hamlin knew he would not relinquish that attention. It seemed even the servants were leaning a little closer to hear his answer.

“Our own Catriona Mackenzie helped her.”

“Airson gràdh Dhè,” Miss Mackenzie muttered, the meaning of which was not known to anyone in this group. “I beg you, Uncle Knox, donna say more!”

“She’s a daring girl in her own right,” he said. “Her own father expressly forbid her to associate with known Jacobites, and yet my beautiful, compassionate niece could not let those young men die! She brought many of them to Kishorn herself.” He sat back, nodding at the looks of shock around him. Miss Mackenzie looked as if she wanted to crawl under the table. “What’s the matter, darling? You’re not ashamed, are you?”

“No!” she said emphatically. “But you are needlessly distressing your guests, uncle.”

“They’ve no grounds for distress!” he proclaimed. “I will have you all know that I mean to help her. What sort of men are we to punish a woman’s true compassion? Is that not what we all seek from the fairer sex? The Lord Advocate contends the property is forfeit for housing those traitors a decade ago, but by God, I shall have something to say for it.”

Miss Mackenzie groaned softly and bowed her head.

“And what have you to say for that, Montrose?” MacLaren challenged him. “Is the property forfeit?”

“I’ll no’ pass judgment on events for which I donna have all the facts, sir, and I’ll no’ do so here for your entertainment.”

A ghost of a smile appeared on MacLaren’s lips. If he wanted to find reason to deny him the vote, then so be it. But Hamlin would not be goaded into making a pronouncement on Miss Mackenzie’s good intentions.

“I beg your pardon, Lord Norwood, but what have these women to do with the rebels?” Miss Wilke-Smythe asked.

“You see, don’t you, my dear, that once the rebels slipped away, it was only natural that women and children who had lost their protectors and providers to the same battlefield and desertion would follow? And once they were gone, others who had no place to go, no way to feed their children came behind them. It was a noble calling that Zelda and Catriona undertook.”

“I would argue that,” Furness sniffed. “Seems rather foolhardy and ill-advised to me. Precisely the sort of thing one can expect to happen when one leaves aunts and daughters to their own devices without proper arrangements for marital supervision.”