Читать книгу The De Zalze Murders - Julian Jansen - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеThe day dawns red

IN AN UPSTAIRS BEDROOM, the attacker has gone berserk. Ruthlessly, his forceful axe blows strike the head of the dark-haired young man. He is strong and agile and swiftly overpowers his victim, like a predator its prey. His quarry defends himself with his hands, desperately trying to ward off the blows. He fights to keep death at bay. But death looms over him.

More blows follow. And yet more. He grabs at his attacker. Slashing through the air, the axe cuts his left hand. The little finger hangs from a piece of skin. Blood spurts down his neck, over his bare torso, and down onto his boxer shorts.

He starts stumbling. Breath rattling, he falls face down. His body comes to rest on his bed, limp.

A grey-haired man rushes into the bedroom. The nightmare from which he woke with a start was no dream, but the cries of death. He stops, shocked, at the bed on which his older son lies, and it is there the killer strikes, raining down axe blows – mainly to the back of the older man’s head. Death comes quickly.

His wife and teenage daughter, terror-stricken, are fleeing down the passage towards the stairs leading to the ground floor. They have to pass the room where the screams have now fallen quiet.

The attacker blocks their path. The mother rushes straight at him. She is hit on the nose. Then he aims at her head with the axe. She tries to hold him off with her right hand, and the weapon strikes her thumb and upper head. Her head snaps forward. Now he has the back of her skull in his sights. Hacking blows hit it with enormous violence. She falls down.

And does not get up again.

The axe wounds the blonde girl on the right side of her head. She collapses next to her mother, her jugular vein partially severed.

***

The summer sun is rising behind the Jonkershoek mountains as domestic workers walk to work on the De Zalze golf estate outside Stellenbosch shortly after seven o’clock. They can’t believe their eyes: in front of a double-storey house in Goske Street stands a bloodied, half-naked young man. Dressed only in grey sleeping pants and short white socks, he is preoccupied with his cellphone. The curious audience grows as the young man with the dark-blond hair talks on the phone, but no one can make out anything of the conversation.

At 7:12 am he calls the 107 emergency number. Janine Philander, an operator at the public emergency communication centre in Cape Town, answers. She puts the call through to the ambulance services at Tygerberg Hospital in Parow. A female operator speaks to the caller and Philander1:

OPERATOR: Ambulance services. Good morning.

PHILANDER: Morning. Janine, 107. I’m speaking to?

OPERATOR: You’re speaking to Christi, Janine.

PHILANDER: Christi, I have a caller on the line. They’re on some winelands there in Stellenbosch, but the address is a bit tricky … Uhm … three adults. One teenage girl. One adult is on the line. His name is Henri.

OPERATOR: Henri?

PHILANDER: Yes. They were assaulted now with an axe. No suspects on scene. He says … I’m going to conference you. Want you to hear this. Hold. Henri?

HENRI: Yes.

PHILANDER: I’ve got ambulance services on the line. So, he gave me a few different addresses. The one he’s gonna go with, he says, is 10 Allemann Street. In Stellenbosch.

HENRI: Yeah. If you go to 10 Allemann Street. Are you sending one there?

OPERATOR: OK, tell me, what is your street name?

HENRI: My street name is Goske.

OPERATOR: OK, die straat waar die incident is? [OK, the street where the incident is?]

HENRI: Yes … it. Yes.

OPERATOR: OK, wat’s die straat se naam? Goske. [What’s the name of the street? Goske.]

HENRI: Goske. Goske Street.

OPERATOR: Goske. G-O-S-K-E.

HENRI: Yes, Goske, in Stellenbosch.

OPERATOR: Is it a street name? OK. Let’s just check this. Hold for me.

OPERATOR TO PHILANDER: Kry jy daai straat? [Do you find that street?]

PHILANDER: No, I get … a Bothasig in Milnerton.

HENRI: If you just, 10 Allemann is just past my street. If you send an ambulance.

OPERATOR: Is it Allemone or Allemann?

HENRI: Allemann.

OPERATOR: OK, spel daai vir my, ek wil gou hier opskryf. [OK, spell that for me. I just want to write it down.]

HENRI: A-double L-E-M-A-double N.

OPERATOR: A-double N.

HENRI: Alle-mann with two n’s.

OPERATOR: I’m not picking it up.

PHILANDER: Let me just write it here on my thingy.

OPERATOR: Is it number 10, neh? Al-le-mann.

HENRI: Do you get any Allemann Street? You can send anybody and I can meet him there in the road.

OPERATOR: Allemann Street. Not Anemone. It’s Allemann?

HENRI: Yah.

OPERATOR: In which area of Stellenbosch is it?

HENRI: Hi. It’s in De Zalze.

OPERATOR: Pardon?

PHILANDER: De Zalze.

HENRI: Called De Zalze.

OPERATOR: Watter area in Stellenbosch is dit? [What area in Stellenbosch is this?]

PHILANDER: De Zalze. D-E-Z-A-L-T-S-E.

HENRI: No, D-E-Z-A-L-Z-E. [Philander spells along with Henri.]

OPERATOR: Zalze. OK, golf estate.

HENRI: It’s a golf estate.

OPERATOR: OK, OK, what kind of injuries is this?

HENRI: Uhm … My… My… My… family and me have been … were attacked … by a guy with an axe.

OPERATOR: With an axe … unconscious, huh?

PHILANDER: They’re unconscious, he says.

HENRI: Yes … and bleeding from the head. [He gives a nervous giggle.]

OPERATOR: OK … die adres [the address]. OK. Just want to get the right thing here. Hou aan. [Hold on.]

[No conversation for 23 seconds.]

OPERATOR: OK. Hold on. You say it’s number 10 Allemann Street. De Zalze golf estate in Stellenbosch?

HENRI: Yeah.

OPERATOR: OK, thank you, sir, we’ll send a … just keep your cell open in case they get lost.

PHILANDER: OK.

HENRI: OK. Call on my mobile phone. Call on my mobile phone. I will be out in the street … meet the ambulance there.

OPERATOR: OK then. OK.

HENRI: How, how long will you …?

OPERATOR: It won’t be long … We’ll send an ambulance out as soon as possible. OK then.

PHILANDER: OK.

OPERATOR: Thank you, sir. Goodbye.

PHILANDER: Bye-bye.

***

Just before half past seven a police vehicle turns hurriedly into the narrow Goske Street. A neighbour had already called the 10111 emergency number when he realised something strange was happening. The vehicle stops in front of the white double-storey house with the two young trees. Sergeant Adrian Kleynhans and Constable Marius Jonkers jump out, removing their service pistols from their holsters as they walk. The sergeant scans the surroundings, and sniffs the air, as if he smells danger. At the white garage door he jiggles the handle to see if it is locked. Then he looks though a chink in the curtains of the window to the right of the front door. The room inside is dark.

The next moment he bumps into Henri, who has a cellphone in his hand. Sergeant Kleynhans is even more on the alert when he sees the blood on the young man’s body and sleeping pants. He asks him who he is, what has happened, what is wrong? Henri just mumbles something and, rather casually, points to the top floor.

‘The problem is upstairs,’ he says softly, and continues fiddling with his cellphone.

The police officer orders Henri to wait outside on the stoep. Then he enters the house, his guard up.

Inside, it is silent as the grave. To the right in the tiled entrance hall is the staircase, with elegant black railings. The officer notices a dark-red wet spot on the shiny beige tiles. It seems to come from the first floor.

He walks up the stairs. Cautiously. A sour, metallic smell hangs in the air. The officer expects the worst. The scene on the top floor stops him dead in his tracks: the bodies of two scantily clad women lie in the passage near the bedroom door, next to a bookcase. The older woman is dressed in beige panties and a navy-blue vest. She has gaping head wounds. Her face is pallid.

The young girl’s long blonde hair is bloodstained. She looks as if she is asleep.

Sergeant Kleynhans tightens his grip on his firearm; someone may still be hiding in the house.

He has shared grisly crime scenes and videos on social media to see the reaction of his friends. But the gruesome scene facing him now is real and immediate, not just a film. He experiences it through all his senses.

Carefully, he enters the nearest bedroom, his ears cocked for the slightest hint of danger. A grey-haired man is slumped over the top end of a single bed in a kneeling position, his legs on the floor. His body and multicoloured striped boxers are bloodstained. On the floor a mutilated dark-haired man, wearing blue striped shorts, lies facedown.

As he walks past the women in the passage, one of the girl’s legs twitches slightly; a macabre sight, almost like a corpse suddenly coming to life. She is alive! The sergeant phones his shift leader at once.

***

At the Stellenbosch detective branch in Adam Tas Avenue, Colonel Deon Beneke is leading the daily parade. The detective branch is housed in an old red-roofed double-storey building, a stone’s throw from Papegaaiberg. For years, a plantation of pine trees covered the slopes. Now the hill is bare, the trees all felled.

His diary is open at Tuesday, 27 January 2015. He and the detectives are discussing the day’s work programme and the progress made with dockets. Later they will decide together which cases should enjoy priority.

The colonel’s police cellphone interrupts the meeting. He grabs it. The caller is Constable Zuko Matho, the night shift’s service leader. By eight o’clock Matho would usually have collected all the dockets, submitted a report on the night’s events, and ended his shift. Then he’d drive the short distance to his home in Kayamandi, have a light breakfast and go to bed.

But today he was summoned to the De Zalze golf estate, just outside Stellenbosch. There was already a commotion at the main entrance when he arrived; a security patrol had reported to the centre at the gate that there was serious trouble in Goske Street.

‘Pipe down!’ Beneke calls out rather irritably to the chatting detectives in their chairs before he can continue his phone conversation. His expression is grim. Hunched forward in his seat, he listens attentively to Constable Matho’s report. His right eyebrow rises slightly as he starts jotting down details in his notebook in front of him. Noting the surprised look on his face, the detectives itch to know what he is being told.

He ends the call. ‘There’ve been three murders,’ he announces, and briefly gives them the details. They stare at their colonel in shock. His pumpkin-coloured shirt fits rather tightly over his stomach. Some of his colleagues anticipate that, one day, the buttons will pop off.

‘Do things like this happen in Stellenbosch?’ Beneke later wonders aloud. Since starting his work as head of detectives in the vibrant student town, he hasn’t had to deal with much violent crime.

A captain next to him remarks drily: ‘Lately it’s really only been the balaclava gang that terrorises the area.’

‘Yes, but even they don’t kill; just tie up their victims,’ a colleague observes.

Some of the other detectives nod in agreement.

Beneke lifts an eyebrow abstractedly. He assigns the task of leading the axe-murder investigation to Matho. The constable is therefore in charge of the crime scene. From now on, no one may enter the scene without his permission, and without being accompanied by him.

The colonel dismisses the meeting but asks some members of the Serious and Violent Crimes Unit to stay behind. Among them are sergeants Stephen Adams, Marlon Appollis and Denver Alexander.

The day-shift members should go along as well, Beneke adds. He himself will also drive to the scene after he has summoned the teams from the Forensic Science Laboratory in Plattekloof in Parow outside Cape Town, and the Local Criminal Record Centres of Paarl and Worcester.

He allocates the tasks, then walks out of the main building towards the row of parked cars and gets into his vehicle. Thoughts are churning through his mind: a murder inside the high-security estate is sensational. But three murders – and with an axe at that – are unprecedented.

The drive to De Zalze usually takes about five minutes. This morning though, with the bustling traffic and the students who have started returning to university, he needs an extra dose of patience.

When the police officers and the various units arrive at 12 Goske Street, Detective Constable Matho accompanies each individually along the designated route to the horrific crime scene on the top floor.

***

In the Naspers Centre in Heerengracht, Cape Town, the reporters in Rapport and Die Burger’s combined newsroom on the sixth floor have been at work since early morning as usual. Our Tuesday news lists have to be finalised for the editorial conference at nine o’clock. As January is ‘the silly season’, the list of newsworthy stories is rather slim. I carry a mug of coffee to my desk, ready to start the day. Someone is mixing instant porridge in a bowl. Here and there fingers are already rattling over keyboards.

Outside the 26-storey building the morning sunlight falls on the slopes of Table Mountain. The cableway is a pencil line against the dark crags and pale-blue sky. Heavy traffic trundles into the city. Ships lie at anchor in the harbour, where the reflections of the sunlight glitter on the sea’s ripples. The Mother City is gearing up for the working day.

The next moment, my cellphone beeps. I glance at the message: ‘Family at De Zalze hacked to death with axe. Child survives.’ Like a newspaper headline. A ‘What the fuck!’ escapes my lips. I put down my coffee mug and call the person who sent the message. The details are still patchy, the sender informs me. In quick succession, other reporters in the room receive the shocking news. Via SMS, e-mail, phone call or on WhatsApp.

Disbelief and shock mingle with questions. A family? An axe? Three dead? Some colleagues start speculating that it may be the handiwork of the notorious balaclava gang that has been terrorising the Kuils River-Stellenbosch region with burglaries in the past weeks. ‘Scumbags!’ a reporter exclaims. ‘It must have been more than one person – to have managed to massacre almost an entire family, to overpower them in their sleep. There must have been a terrible fight, resistance … An axe?’

‘Get as much information as possible and keep a close watch on the daily papers during the week,’ our news editor, Inge Kühne, instructs from the Sunday paper Rapport’s offices in Johannesburg. We send text messages to all our police contacts. The internet is combed. The search terms: ‘axe’ and ‘De Zalze’. The traps are set for any incoming news on this breaking story.

***

In Goske Street, the area around No. 12 has become a hive of activity. In front of the house the police and forensic teams in their light-blue overalls and gloves are hard at work.

Warrant Officer Nicky Steyn also arrives at the scene. He and his colleagues were working on an investigation involving the balaclava gang when they were called to De Zalze, and immediately rushed to the Goske Street house. Perhaps he can pick up the trail of the gang on the estate, Steyn hopes. If they are, in fact, the perpetrators.

Two ambulances, with the paramedics Victor Isaacs, Axel Mouton, Marco Jones and Christiaan Koegelenberg, are already at the scene. After the call from the emergency centre in Parow, they wove their way through the heavy morning traffic from Stellenbosch’s ambulance station in Merriman Road to the estate with screaming sirens.

Detective Constable Matho conducts the paramedics upstairs and looks on as they kneel next to each victim in turn, checking for signs of life. Three times they just shake their heads. No pulse, no breathing.

Squatting down next to the unconscious girl, a paramedic checks her pulse to make sure her blood is circulating. One checks for an obstruction in her airway, then another makes sure she is breathing comfortably. She has a gaping wound to her head; her jugular vein seems to be severed. The paramedics staunch the bleeding and bandage the wound. They lift the girl carefully onto a stretcher that has been hurriedly brought in. She groans. They need to get her to Mediclinic Stellenbosch as soon as possible.

The paramedics’ boots leave a bloody trail from the top floor to the ambulance.

Outside the house, the task of attending to the large bruise on Henri’s forehead falls to Victor Isaacs. There are also two long, thin marks across his chest. He has a superficial blueish stab wound to the left side of his body. No blood flowing from it. There are three thin scratches to his left arm. The paramedic shines his torch into the young man’s glazed eyes to check how the pupils react to light. The pupils contract abnormally, which surprises Isaacs and his colleagues as it may be an indication of an unknown substance in Henri’s bloodstream.

Isaacs is already haunted by the scene, and particularly the horrific wounds sustained by the victims. As he packs away his equipment and peels off his gloves, he is overcome by sadness. It would take the whole team a long time to get over what they had just seen.

Members of the police’s forensic unit place a bloodstained axe and a kitchen knife, apparently part of a set, in transparent plastic bags, and label them. The items will be tested for DNA as well as for so-called ‘touch DNA’ (DNA that is transferred via skin cells deposited on an object whenever it is handled or touched).

The axe looked brand-new, according to those who caught a glimpse of it.

Meanwhile, reporters, photographers and a television team have dashed to De Zalze. At the main entrance, they are stopped firmly by security personnel. Other entry plans have to be devised to reach Goske Street. Two reporters try an alternative route via the adjacent Kleine Zalze wine estate, from which they discover an access route to De Zalze, and manage to get near the house in Goske Street.

From behind the cordoned-off area they send out tweets, take photos of police officers and the forensic team, and talk to some of the neighbours. The bystanders’ eyes are fixed on the double-storey house, shock and incredulity on many faces.

Among them is Felicity Louis, a domestic worker on the estate. Earlier, she saw Henri standing in front of the house. His blue eyes were dark, almost vacant, she recounts. ‘His eyes had such a funny look, as if they were looking far, far into the distance. He just stood there.’ Apparently urine was running down one leg, into his sock. ‘He even waved at the neighbours.’

In the back seat of a parked police vehicle sits the family’s domestic worker, severely traumatised. She arrived at the house early in the morning – even before the first police officers turned up – and went upstairs, where she saw the bodies and ran out of the house screaming hysterically. It is all still too much for her. Every now and again she sobs quietly. A policeman brings her a new handkerchief and a glass of water.

Martin Locke, a neighbour of the family and well-known SABC TV sports commentator from the 1980s, watches from beyond the cordoned-off area with his blonde fiancée, Jeanette. Today is his 75th birthday, and this afternoon he and Jeanette are getting married. He calls out to Henri, who is standing to one side, but the young man just stares ahead. Later Martin walks off and watches from further away as the police and members of the forensic unit remove black plastic containers from a vehicle and carry them into the house. Another neighbour stands next to him. Now and then they exchange hushed comments.

A resident who lives lower down in Goske Street confides from behind a hand that in the early hours some of the neighbours heard sounds of a ‘row’ coming from the house.

Later Henri’s girlfriend, Bianca van der Westhuizen, arrives after having seen all his calls on her cellphone. She is accompanied by Alex Boshoff, a close friend of Henri. Bianca is inconsolable and Henri puts his arm around her. He is crying unashamedly. Alex comforts his friend and cries along with him.

Also standing in front of the murder house is André du Toit, Henri’s uncle on his mother’s side. The estate management summoned him urgently, but reportedly Du Toit wanted to know why he was needed before taking on the rush-hour traffic from the northern suburbs of Cape Town. On hearing the news, he sped to Stellenbosch in his double-cab bakkie.

His brother-in-law had given André’s name and contact number to the management the year before, in case of an emergency. Little did he know what the nature of that emergency would be.

Meanwhile, more reporters and photographers who have caught wind of the route to the house via Kleine Zalze arrive in Goske Street and congregate behind the police’s crime-scene tape. At this stage the media do not know exactly where in the house the bodies are lying. Apart from the fact that the Van Breda family lives here, information about the attack and the victims is still extremely scarce. Those who do obtain any details share them in whispers or jot then down quickly in a notebook.

On Facebook, the profiles of the daughter, Marli, and her brother Rudi show that the family previously lived in Perth and Brisbane, Australia. The digital rumour mill has started grinding, and Twitter is abuzz about the murders.

Forensic teams in their protective suits and gloves, escorted by a patient Constable Matho, still move in and out of the house. It looks like a scene from a thriller.

Photographers struggle to get a frontal shot of the murder house. The cordoned-off area stretches up to three houses from No. 12. The police and emergency vehicles, as well as the two trees in front of the house, obscure the view even more. Photographers have to be content with side-view shots taken from the neighbouring houses. Some obtain permission to take photos from the neighbours’ balconies but still can’t get a good view. The police officers keep a stern eye on the media. No one dares move beyond the yellow-and-blue tapes.

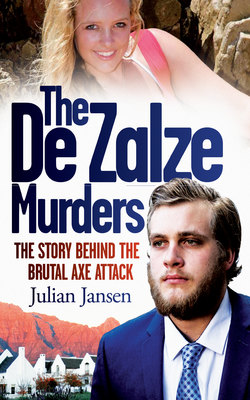

As the hours go by, the bigger picture starts taking shape: the 54-year-old Martin van Breda was an affluent businessman. His wife was the 55-year-old Teresa, a homemaker. Rudi, their eldest child, was a 22-year-old student at the University of Melbourne. Their other son is 20-year-old Henri. Their daughter Marli, aged 16, attends a private school outside Somerset West. The family is originally from Pretoria. The upmarket suburb of Waterkloof Heights.

Most of their relatives still live in Gauteng and Mpumalanga. Among them are Teresa and André’s 90-year-old mother, Rika du Toit, who lives in a retirement home in Kempton Park. She suffers from Alzheimer’s disease and when told that her daughter, son-in-law and grandchild have been murdered, does not grasp the full meaning of the shocking news at first.

André and his wife Sonja start a WhatsApp group to keep the extended family abreast of developments.

Members of the media still thronging the main entrance in the late-afternoon sun are enormously relieved when Eben Potgieter, chairman of the De Zalze homeowners’ association, and Boet Grobler, the estate manager, finally invite them in for a news conference.

Immediately after the bodies in the house were discovered, Eben says, he instructed the security convenor on the estate to establish whether the perimeter fence had been breached in any way. He emphasises that there is no sign of forced entry into the estate. No one signed the visitors’ register to visit Goske Street the previous day or night. According to him, there also seem to be no signs of a break-in at the house concerned. It appears to be an ‘isolated incident’. He is absolutely sure of that.

***

Earlier in the day the police took Henri in for questioning. To some detectives, the young man appeared quiet; although the shock may cause him to act strangely, they thought. Others recounted that he ‘reeked of alcohol’ and was ‘cocky at first’. But his attitude reportedly changed later when an officer remarked out of the blue that his sister had ‘started talking’.

In his witness statement, Henri said that an ‘unknown person’ attacked his family. He had been in the bathroom of the upstairs bedroom he shared with his brother. When he came out, he saw the intruder (whom he described in the statement) attacking his brother with an axe. He was too afraid to help his brother. The intruder subsequently attacked his father, and then his mother, and finally his sister.

He threw an axe at the attacker; a fresh mark on the wall substantiated this, he said. He fell on the stairs and was knocked out. Some time afterwards he regained consciousness and called the emergency services on his cellphone, according to his statement.

The sun has already set when André and his wife, Sonja, took Sasha, Marli’s beloved black dog from Australia, with them to their home in Welgelegen, about 17 kilometres outside Cape Town. There they watch the television news about the gory axe murders of a respected businessman, his wife and their elder son in their white double-storey home on a quiet street in an exclusive winelands golf estate.

Back in Somerset West, where Marli has in the meantime been transferred to the Mediclinic Vergelegen, surgeons battle to save the blonde girl’s life. If she survives, will she be able to talk? If so, what will her account of the night’s events be?

1 Transcript of recording of call to emergency services as broadcast on eNCA.