Читать книгу Adventure Capital - Julie Kleinman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

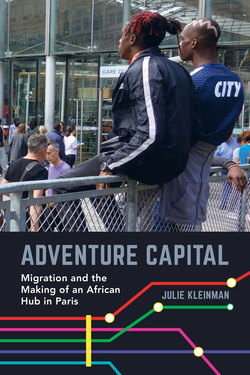

On a breezy spring day in 2010, Lassana Niaré1 and I sat sipping espressos at a café across the street from the Gare du Nord railway station in Paris. We gazed at the station’s glass-walled entrance, where groups of young West African men stood chatting as people brushed by them on their way into the busiest rail hub in Europe. Originally from a village in rural western Mali, Lassana had been living and working in France for almost a decade. He and his West African comrades met most evenings at the Gare du Nord, which they passed through on their evening commute.

I had first met Lassana the previous fall in the station’s front square. At the time, he sported neat cornrows in his hair and wore baggy jeans, a jersey emblazoned with “The Bronx,” and a backwards Yankees cap. He had come to France in 2001 on a three-month commerce visa and spent the better part of his twenties barely getting by as an undocumented cleaner and construction worker. He and many other West African workers came to the station for various reasons: to catch up with friends and discuss the news, find better jobs, get loans, and meet new people. For them, the station is more than a simple transit site.

“We are adventurers here,” Lassana used to say—not foreigners, guest workers, refugees, or migrants. Many West Africans I met in France used the terms l’aventurier (adventurer) and l’aventure (adventure) to describe themselves and their situation. It was not just an attempt to romanticize difficult journeys and hard times.2 These terms and their equivalents have long been used among West Africans to signify that migration is an initiatory journey, a rite of passage.3 Seeing their voyages as part of a broader tradition helped to maintain connections to their families across long distances. It gave migrants a way to find meaning in risky travels and misfortune abroad.4 “Soninke are the greatest adventurers,” Lassana once bragged, referring to his ethno-linguistic group that comprises about two million people in the Western Sahel (a semi-arid region just south of the Sahara including parts of Mali, Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea, Gambia, and Burkina Faso) but which also has a significant global diaspora. His father and uncles all had left on adventures in their youth; most of his brothers and cousins were on their own adventures in central Africa and Spain. The notion of migration as an “adventure” was widespread among migrants at the Gare du Nord as it is with migrants from this region living across the globe.5

Lassana’s vision departed from the assumptions of so-called “economic migration” applied to migrants like him, which assumes that migration is a relatively new phenomenon where poor people are forced to leave underdeveloped villages in Africa and go to work in European capitals.6 Lassana, rather, saw migration as a necessary stage of life and the continuation of a long tradition. He was not alone. Many West African migrants come from places where “not migrating is not living,” as anthropologist Isaie Dougnon puts it.7 The idiom of adventure is a way for Lassana and other West Africans to conceptualize their journeys. It also provides a new perspective for understanding migrant lives and struggles more broadly.

The notion of migration-as-adventure challenges the nation-state definition of immigration, which presumes that the migrant moves from one bounded entity into another with the goal of settling and attaining citizenship, and often, in the xenophobic imaginary, of relying on state subsidies. Instead, adventurers live by the ethic of mobility, producing social and economic value by creating new networks for exchange, and making the most of what anthropologist Anna Tsing calls “encounters across difference.”8 Lassana and his friends see the Gare du Nord as the ultimate place to carry out their adventures. Instead of remaining within the well-trodden paths of kinship and village ties, they use the station to meet people outside of their communities, people who might help enable their onward mobility and realize future-looking projects. Adventurers have transformed the largest rail hub in Europe, and the Gare du Nord has changed their life course.

On the day we met for coffee across the street from the station, Lassana asked me how my research on the station was going. “Bit by bit,” I responded, some of the discouragement coming through in my voice.

“It’s good you’re writing a book. This is what matters,” Lassana replied reassuringly. “The important thing is to have projects, to think of the future, keep moving. Avoid getting stuck.” This advice reflected Lassana’s adventure ethos, which sought constant forward movement: he told me that he hoped to meet a German woman at the Gare du Nord, move to Germany, and find something better than underpaid construction jobs in France. Now that he had the resident permit, he wanted to go elsewhere.

As we sat at the café, a small TV set above the bar drew Lassana’s attention, interrupting our conversation. The screen showed a few white people on a boat throwing life-vests toward hundreds of black people in the water. The disembodied journalist’s voice intoned: “In the Mediterranean Sea between Africa and Europe, a boat filled with migrants has sunk. The nearest coast guard mounted a rescue, saving some, but many have drowned.”

“We already know this story,” Lassana said.

He was right: the sinking of unseaworthy vessels “filled with migrants” was frequently reported in the media in this way. In this saga linking two sides of the Mediterranean, we knew the tragedy’s denouement: survivors would bring the terrible news to their villages, and families would try to locate their kin from afar. In the days that follow, bodies would wash up on pristine European beaches, or would be tugged out of the water by Frontex (European Union border control) ships. Many would never be found.9

Lassana narrowed his eyes at the screen, furrowing his brow. It was as if he were trying to see whether he recognized anyone. I learned later that he was trying to see if he could tell where the surviving “Africans” had come from by looking at them. But the camera panned over the migrants, returning to focus on the people in the boat as they pulled men, women, and young children aboard.

We already knew this story, as Lassana said, because of how dangerous Africa to Europe migration routes have become. European Union and member-state policies have criminalized migration by shutting down legal pathways to Europe, reinforcing border control, and detaining and deporting undocumented migrants.10 Rather than dissuading people from migrating, these policies have led migrants to seek more perilous routes, such as crossing the Mediterranean in ill-equipped and unseaworthy vessels. Between 2000 and 2014, it is estimated that 22,400 people died attempting to enter Europe; more than 5,000 people died trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2016 alone.11

For Africans who have made it to Europe and have been living there for years or even decades, the tragedies in the Mediterranean strike close to home. Their brothers and sisters are taking grave risks to go abroad. Like Lassana, many West African migrants in France come from places where migration abroad is a rite of passage for young men: to remain at home is to feel stuck forever.12 When they are denied visas at the consulate in their home countries, as most poor migrants from the global South now are, they will set out for the desert and march toward the sea, paying smugglers and joining the many refugees fleeing conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

As many scholars and activists have shown, the EU could prevent these deaths in border zones (such as the Mediterranean and the Saharan desert) by providing legal paths for those who migrate. Instead, EU policies make migrant death more likely as European border control creeps further into the African continent.13 Those who make it across face detention, deportation, and perilous onward journeys. Even those who get papers feel trapped, unable to return to their villages for fear that their temporary resident permits would not allow them to reenter Europe.14 Some migrants will make their way further north with the hopes of gaining passage to England. They set up makeshift camps, a few around the Gare du Nord and others in northern French towns like Calais, which get periodically torn down. Several people have died trying to get to the United Kingdom via the underground tunnel built for the Paris-London Eurostar train.15

The Gare du Nord has become part of these border zones and the violence they enact. Despite being thousands of kilometers from the Mediterranean, and three hundred kilometers from France’s northern border, the station operates the Eurostar rail line that takes passengers through the Channel tunnel to London. As a result, there is a legal border within the Gare du Nord that passengers to the United Kingdom must pass through before they board. In May 2017, an unidentified refugee was electrocuted and died at the station while trying to jump onto a London-bound train. He was not the first to die this way. The trappings of the border and those who enforce it are everywhere in the rail hub, including military patrols and customs agents, British immigration officers, two types of the French national police, railway police, and private security.

Like many railway stations across the world, the Gare du Nord has also been a magnet for those who exist on society’s margins, often excluded from full participation in urban citizenship. More than any other Parisian railway station, the area is known as a site where homeless people, sex workers, teenage runaways, petty criminals, and drug users congregate alongside the throngs of passengers taking international trains. Since 2009, the Gare tended to be in the news for one of two reasons (based on tracking Google alerts): a police action following “gang fights,” drug trafficking, or youth delinquency; or the arrival of an international celebrity on the Eurostar train. French literature and filmmaking represent it as a site of encounter, danger, and/or criminality.16 The neighborhood around it has been formed by successive waves of migrants, from rural French to southern Europeans to North and sub-Saharan Africans to South Asians, leading tourist brochures to describe it as “exotic” and “colorful.”17

The station has been used as an example of France’s urban ills, a dangerous and seedy locale where African immigrants and their descendants were accused of taking over Parisian public space. “You arrive at the Gare du Nord, it’s Africa! It’s no longer France!” exclaimed Nadine Morano, former French government minister and congresswoman, while being interviewed on French television. In a similar vein, I heard several white French people refer to it as “la Gare des Noirs” (the Noir/Black Station) instead of the Gare du Nord (the North Station). I will return later in the book to both of these racialized representations, which are interpreted differently in the station’s social world. According to the head of John Lewis, one of the biggest English department store chains, the station is “the squalor pit of Europe.” In the popular imaginary of many commuters from the Paris region I spoke to, the Gare is an unavoidable nuisance that they must pass through to get where they are going.

But the violence of the border and the presence of society’s excluded does not define the station. In the social imaginary of many migrant communities, it has taken on other meanings. For example, for the Algerian-French novelist Abdelkader Djemaï and the chibanis (Algerian retirees) in his novella Gare du Nord, the station is a symbol of warmth and connection holding the promise of distant lands: “As soon as they approached the Gare du Nord,” Djemaï writes of the chibanis, “They felt attracted by its warm atmosphere, its feminine forms, and by the soft light that had the color of a good beer. It was the port where they debarked depending on their mood and their imagination.” Although the station also reminds them of their precariousness, their “fear of ending up homeless like all of those on the sidewalks of the Gare du Nord,” it remains a mobile home-away-from-home, fitting to lives woven in the interstices of urban life in France.18 Or as writer Suketu Mehta speculates, “Maybe what keeps the immigrants in the area, is the knowledge that the first door to home is just there, in the station, two blocks away. The energy of travelers is comforting, for it makes us feel that the whole world, like us, is transient.”19 These narratives anchor the station to the immigrant history of northeast Paris where it is located. They evoke the aesthetic of movement as one of the factors that draws so many to the station.

Lassana and his adventuring peers often used the word “crossroads” to describe what they appreciated at the station; unlike segregated spaces of the Paris capital region so often studied in the scholarship on migration, it brings together people from all backgrounds.

“We all started out in the immigrant dormitory,” Lassana used to say, referring to the foyers built in the 1950s in France to house foreign workers. “But we didn’t stay there very long, we didn’t want to put ourselves on the sidelines.”

His friend Mahmoud, an older Pakistani man who had been in France for decades, agreed. “You don’t want to be on the sidelines, so you come to the Gare du Nord,” he said.

Many migrants saw the station as a site of convergence and social potential. Lassana and his peers also said that it helped them to understand and live in the “real France”: the one hidden by media representations and invisible from the “sidelines” of suburban housing projects and immigrant dormitories.

BEYOND BORDERS

By examining the intersection of West African adventures with the Gare du Nord, we can disrupt the “story we already know” about migration and integration, and offer other stories too often obscured by the focus on border violence, detention, and deportation in the media and in scholarship.20 Even when intended as critique, the media spectacle of migrant death and the emphasis on the repressive tactics of policing and security often end up enhancing the visual impression of states’ power to exclude undesirable populations. The focus on borders, camps, and the security apparatus enacting dramatic forms of exclusion at entry points and in transit zones tends to neglect the way that migrant experience is also defined by the more banal functioning of a capitalist market system in which migrants are included but as subordinate members of a social, economic, and political system that offers them few rights and privileges while requiring their labor, a process anthropologist Nicholas De Genova calls “inclusion though exclusion.”21 The focus on repression also tends to ignore the failures and gaps in state-made exclusionary measures and the ways that migrants have contributed to the making of Europe and its urban spaces.

Lassana and other West African adventurers use the station to challenge “inclusion through exclusion” and build an alternative form of meaningful integration via urban public space. I have chosen to use the controversial word integration not as an analytical concept but as a provocation and to displace some of the commonsense ways of thinking about what integration means and what it could look like, especially since rural migrants from West Africa are often presented as refusing to integrate. The term is used in French state immigration policy (including the now defunct “High Council of Immigration”) and political speech, usually to imply that certain communities—most often Muslims and people of color—have failed to “integrate” in an acceptable way.22

At the Gare du Nord, migrants develop new strategies to work around the restrictions placed on their mobility by French policies and migration restrictions put into place since the 1970s, policies that created the category of the “clandestine” migrant.23 The 2008 economic crisis and the 2015 “migration crisis” have created further obstacles to migrant livelihoods by fueling nationalist political movements and making it more difficult for migrants to find jobs and secure legal status.24 When their sojourns abroad started to extend to over a decade and the signifiers of status and success escaped their reach, migrants began to seek new ways to attain their goals in France.

It was in this quest that West African adventurers have developed what they call the “Gare du Nord method,” a set of practices and an overall moral orientation through which they seek to create new channels to produce value abroad. This approach is based on combining the lessons of courage and discipline taught in their village upbringing with the strategies they learned on the road across West and Central Africa, and the knowledge they gain in France. Through it, they seek to create value through social relations and systems of exchange and reciprocity. The result of their labor, I argue, is the creation of an African hub: not a cultural enclave of “Little Africa,” but a hybrid node of communication and exchange in which the material infrastructure of the French state becomes entangled with the social relationships and economic practices of West African adventurers.

Given immigration restrictions that lead migrants to stay longer in French territory, yet policies that exclude them from French public life, West African migrants are using the station to build a pathway toward a more dignified form of integration and mutual belonging that resonates with their adventure. Given their status, the limited form of integration and success they achieve is often provisional and symbolic. The material conditions of their lives, the discrimination they face, and their exclusion from a decent labor market bars them from achieving their plans abroad. Their experiences reveal that French ideals of “social mixing” and positive coexistence (often called le vivre ensemble, or “living-together”) are inflected with what Jean Beaman calls “France’s racial project” based on white supremacy.25 Adventurers offer their own implicit and explicit critiques of that project. Their Gare du Nord method comes much closer than French institutions at actualizing the promise of mutual belonging encapsulated in living-together.

STORIES WE TELL

I am writing this book at a time when we need new models for understanding migrants’ lives and the structures that constrain them. Political ideologies of populist nationalism and economic imperatives that govern migration policy in the global North have created a broken system that is leaving tens of thousands dead at sea and on other perilous migration routes, while also leading to worsening economic and social outcomes for migrants and their descendants who arrive at their destinations. The current modes of managing migration are not working. Liberal models of tolerance celebrate multiculturalism but cover up structural inequalities and state policies of deportation and exclusion. The economic imperative of the capitalist system to maintain an available but restricted pool of migrant labor leads to precarious jobs and hardship. The global management of migration, spearheaded in Europe and the United States, creates avoidable suffering. It is what kills migrants each day. In this context, adventurers recognize that their options for futures abroad are getting thinner. Yet they are spending more and more of their lives far from home, in a permanent state of transit. As their time on the road lengthens to cover the greater part of their adult life, they also become wary of the futures proposed to them by their kin: of settling in their village as a household head in an arranged marriage.

The stories and narratives that we impose on migration play a key role in formulating how we imagine the problems it presents, and, thus, which solutions are possible. A typical narrative, bolstered by a long history of French sociology, from Emile Durkheim to Pierre Bourdieu and Abdelmalek Sayad, highlights that migration is produced by the inequalities of a capitalist market world system that forces people living in collectivist communities to be uprooted and then transplanted as wage laborers to a context where they suffer on the margins.26 Sayad used his sociology of Algerian immigrants in a powerful critique of French modes of integration and immigration management, but French xenophobic rhetoric has recycled the uprooting thesis to blame sub-Saharan African immigration for many problems in French society, from the national debt and rising unemployment to crime and insecurity.27 The infamous 2005 banlieue “riots”? According to several politicians and intellectuals, African family structure and polygamy was to blame.28 The problem, they said, was not with “African culture” but rather with its importation into France. According to this logic, cultural practices became problems and explanations for violence when they left their acceptable place in the “African village” and came to occupy French urban spaces and public housing.29

Another story about migration, used to describe European immigrants to the United States and recently applied to African migration, imagines that migrants are heroic individuals realizing their dreams by breaking away from oppressive conditions and social constraints.30 Both of these stories begin from the assumption that migration is defined by a breaking away that ruptures kin relationships and can lead to social pathology. In both cases, the problem is located in the sending country (it is underdeveloped or uncivilized, or perhaps the social environment is stifling), and so the solution must be focused on migrant culture and sending countries, removing European responsibility for reproducing inequality.

Where will new models and narratives come from? I propose that they come not from academic and policy debates but from the migrants themselves, from the way they see the world through their notion of adventure and the way they configure themselves as adventurers through the public space of the Gare du Nord. From this perspective, they are not ethnographic objects providing evidence of the effects that capitalist market logics and French/EU migration policy have on West African migrants, but rather offer new theorizations of migration and French urban public space, and predictions of what the future might hold.31 If migration is recognized instead as a potential form of social continuity, a normal part of the life course, then the problems that migrants face today in France can be exposed for what they are: produced by French and EU policies that arrest and constrain the mobile pathways of migrants. The solution, then, needs to help enable these pathways instead of further limiting them or making them more dangerous.

The frame of adventure has become a way for West African migrants to make sense of and act in a world of enduring risk, where migrant death on the road has become an ordinary occurrence. Where they could go from employed and “legal” to jobless and “illegal” overnight.32 Where their own capacity to meet their needs and their social obligations to their family are tenuous. Where they are marked by the color of their skin as threatening and fundamentally unlike white French citizens. In the face of border deaths and precarious existences, the Gare du Nord has become a key site in their efforts to make meaningful social ties to help them not only survive in Europe, but to “become somebody,” as Lassana put it, against the odds.

Across the world, migrants are using new strategies to confront difficult circumstances. Much recent work has explored how migrant communities create social networks and community among co-nationals or co-ethnics. Such strategies play into what the French state deplores as “communitarianism,” by which they mean the ways that migrants create enclaves that bar their integration into “French” ways of life.33 Adventurers suggest that this version has it backwards. Instead of building their networks of “co-ethnics” and extended kin in France, West African migrants at the Gare du Nord depart from their kin and village communities to create social ties and families across national, racial, ethnic, and class boundaries. Meanwhile, it is rather the French state that promotes communitarianism through racial profiling, urban redevelopment, and regulations aimed at curbing marriages between French citizens and non-nationals. The adventurer imaginary and Gare du Nord method offer a critique of the French politics of difference and the marginalization it produces, as well as an alternative model for what migration management, migrant integration, and the elusive goal of urban living together might look like.

WHY THE GARE DU NORD?

My attention first turned to the Gare du Nord during the French presidential election campaigns of 2007, when the French nightly news reported that a riot had taken place there following the violent arrest of a Congolese man who had entered the commuter rail area without a ticket. Politicians and news media used the event as evidence that an incursion had taken place: from their perspective, African residents of suburban housing projects had succeeded in bringing the “disorder” of their worlds to the international train station, a vital center of French capitalism. The event sparked a debate over what kind of order the French state should maintain and who could legitimately occupy French public spaces. It helped to confirm right-wing candidate Nicolas Sarkozy’s victory a few weeks later by bringing the themes of insecurity and immigration back to the center of political debate.34

As I began to examine the station and its history, I found that the Gare du Nord, operating as a critical urban space and border zone within Paris, provides an extraordinary site for the exploration of the way borders, state policy, urban public space, and migration intersect in France. Since its construction in the mid-nineteenth century, the station has hosted the political struggles of workers and migrants, as well as state experiments in control and policing. In addition to the meanings it has for many immigrant communities in Paris, the history of the station and its many renovations reveal how racial inequality has been built into urban spaces from their inception. It plays a pivotal role as a site for the government’s efforts to police migration within Paris, connecting the policing of what anthropologist Didier Fassin calls the “internal boundaries” of France to the policing of its territorial borders.35 It is an important site in the social and professional lives of many adventurers and migrants—from nineteenth-century provincial workers arriving in the capital to West Africans like Lassana today. The station is an alternative place for “migrant city-making,” the apt term that Ayse Çaglar and Nina Glick Schiller use to describe how urban areas are produced through the ways migrants build connections across scales (local, regional, and global) when subject to inequality and power differentials.36 There are many railway stations in Paris, but none of them—according to West Africans I met there—provided such a distinctive “international crossroads.”37

FIGURE 1. Aerial photo of the Gare du Nord and surrounding area, 1960. Archives de la Préfecture de Police.

The station’s name designates potential: it proclaims that from here, you can get to the north. All of the trains that leave the station will first pass through Paris’s 10th and 18th districts, both gentrifying areas with halal butchers, sidewalk cafés, a West African market, trendy bars, Turkish sandwich shops, Sri Lankan restaurants, and art deco apartment buildings. The rails then cross under the circular highway that separates city from suburbs and proceeds to traverse the Seine-Saint-Denis, a district that combines high-modernist public housing projects with old town squares. The vast majority of the station’s passenger traffic comes from the commuter rail, built in the 1970s, which brings suburban traffic into the city center. Those train lines include the exurbs or grande banlieue, where picturesque towns and single-family homes give way to rolling farmland. The high-speed lines race through that whole stretch in a blur to arrive in the provincial northern capital of Lille, one hour away, now in commuting distance to Paris. From there, it is one hundred kilometers northwest to the English Channel, where the Eurostar trains will pass through an underwater tunnel, before traversing the English countryside on their way to London. The northeastern route through Lille connects the Gare du Nord to northern European cities of Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam, and Cologne. By the 1990s, over five hundred thousand people passed through the Gare du Nord each day, making it the busiest station in Europe. Today, that number may be closer to one million on some days.38

As a node created by multiple transportation infrastructures coming together, the Gare du Nord has also become a central point of exchange in unsanctioned economic networks and urban hustling, from commerce in stolen cell phones, personal check fraud schemes, and pirated DVD sales to the formalized structures that enable the sale of illegal drugs arriving on the train from Belgium and the Netherlands.39 Networks of Eastern European immigrants have mobilized transportation and related tourism infrastructure to make money from begging practices, which have joined the ranks of “uncivil” offenses (les incivilités) punished by the railway police.40

The station’s social environment has also been produced through the changing legal economy. The establishment of West and North African networks there occurred when migrant settlement patterns in Paris met the process economists call the flexibilization of labor: agencies specializing in temporary day-labor work placements sprang up around the station in the 1970s, and in the morning would recruit construction workers at the entrance. Around that time, African migrants were moving to the cheaper housing in the area and also to the new public housing in suburbs served by the Gare du Nord rail lines. The work agencies are still in the area, though they no longer recruit at the Gare. But many West Africans still meet at the station and use it to find work.

It was no coincidence, Lassana told me, that they ended up at Europe’s busiest rail hub. “It’s an international railway station here,” as he often put it. The potential for movement suffused the station, with fifteen hundred trains coming and going each day and passengers from the world over pouring out of the station’s doors. It is the “true wilderness,” as Bakary, a Senegalese migrant put it, referring to the Gare du Nord as that liminal space of possibility in his migratory rite of passage where, away from his family, he would prove his ability to overcome obstacles and danger.

NEW ADVENTURES: REDEFINING THE MIGRANT’S JOURNEY

When I first asked Lassana what he meant when he referred to his departure from his home village as “leaving on adventure” (partir en/à l’aventure) and to himself and his comrades as adventurers (aventuriers),41 he explained it this way: “We’re all looking for a way to get out of struggle (la galère) and into happiness (le bonheur). But some are not cut out for adventure, and they stay in la galère. But I’m an adventurer. My father was an adventurer. My father was poor. My mother was poor. But my father told me, if you’re born in misery you can end up with happiness, but if you’re born with wealth you can end up in misery. And he told me my pathway would take me far from our home.” The notion of adventure helped Lassana connect his struggles to a tradition passed down from father to son. It offered a framework for interpreting hard times abroad as well as a sense of belonging to a larger community of adventurers.

Adventure was not just another word for migration: it contained a whole world of West African migrant histories.42 Precolonial trading empires and colonial rule have helped shape a flexible cultural idiom for West Africans voyaging abroad. Like all idioms, it is not a deterministic cultural pattern but rather a malleable resource that migrants draw on in different contexts, transforming it as they do so. As Lassana taught me, it provided a template for those who left their families for lands unknown. Sylvie Bredeloup, an anthropologist who has long studied the notion of adventure among West Africans, calls it a form of “moral experience” in which migrants seek personal and social fulfillment through migration.43 Examining how West African migrants understand and express their life course through this idiom sheds light on critical aspects of migratory pathways that are often ignored in policy debates. The adventurer outlook offers a cultural logic and moral template for how life should unfold, and for how people ought to relate to one another.

Seeing migration as adventure does not mean seeing it as a romantic or thrilling odyssey that exists outside of the social realm. “L’aventure” and “l’aventurier” are rather loose French translations of terms from Mande languages spoken by West Africans in France (including the languages Soninke, Bamanakan, Malinke, Mandingo, Jula/Dyula, and Khassonke). The space of this journey is called the tunga/tunwa, an unknown or foreign place, a “space of exile.”44 In Soninke, the word adventure is also translated as gunne (“wilderness/bush”) and adventurer is a translation of gounike/gudunke and other similar terms meaning “the man of the bush” or “the man of the wilderness.”45 These terms point to what makes the West African migratory adventure specific and remarkable: Migration in this case is a rite of passage in which the migrant must confront risk and the unfamiliar to ensure his social becoming. Becoming a marriageable man meant undertaking an initiatory journey during which the migrant is supposed to accumulate wealth before returning home to marry and settle in the village. Migration in this context is seen as a way of reproducing—not dismantling—peasant communities.46

Adventures have a long history. Well before they migrated to France, the importance of commerce and travel among Soninke had already been established through a long history of contact, exchange, and mobility, including trans-Saharan trading empires and caravans that predate European colonization.47 Similar idioms have existed in many parts of West and Central Africa, as Jean Rouch documented in his 1967 film Jaguar about Nigerien migration to Ghana, and as anthropologist Paul Stoller explored in his ethnography and fiction (including his ethnographic novel Jaguar, narrating the present and pasts of journeying Songhay traders from Niger).48 These notions are being updated and transformed in present contexts, such as the recent resurgence and new significations of the term “bush-falling” to describe Cameroonian migration to Europe.49

Islamic religious commitments shape the adventures examined in this book. They provide a moral template for how to act in foreign and fraught situations: Lassana’s father guided him to use the Qur’an to “find the pathway” through Islam while abroad, in order to avoid trouble that could disrupt his voyage. It was thought that going to Qur’anic school was the best training for succeeding abroad because it provided moral discipline. Amadou and Jal referred to the importance of “din” (religion, from the Arabic) in helping them stay on the right path in France. Seeking knowledge and (self-) discovery through travel is based on Islamic traditions, whether in pilgrimage to Mecca and other sites of religious learning, such as Timbuktu, or in voyages to the non-Islamic world, as the writings of the great fourteenth-century traveler Ibn Battuta testify.50

Colonial rule did not introduce mobility, but it would transform the pathways of many adventurers as they became wage laborers.51 Many Soninke continued their mobile traditions by seeking work across the French empire. They took grueling jobs cultivating crops in Senegal or working on the docks in Marseille not because they were forced to by the real burden of French colonial taxes or because they were desperate and disenfranchised, lacking land or wealth and seeking to escape. Rather, as historian François Manchuelle illustrates, migrants were often village nobles who left with the goal of strengthening traditional authority and their own status.52 Voyages have long conferred prestige to migrants.53 There is a saying that I heard several versions of in Soninke and Bamanakan that reflects this notion: “If he who has visited 100 places meets he who has lived 100 years, they will be able to discuss.” In other words, knowledge gained through travel abroad can disrupt a rigid hierarchy based on age, allowing a younger man to exchange and converse at the same level as his elder.54

The adventure has further transformed as structural readjustment policies implemented in the 1980s led to diminished buying power and stagnated social mobility across most of the continent.55 In rural Senegal and Mali, droughts of the 1970s and 1980s compounded the precariousness of rural communities. Transnational migrants sending remittances became “national heroes,” as anthropologist Caroline Melly puts it, taking the place of the diminished state to provide new possibilities for rural communities to survive.56 In addition to house-building, contributing to diaspora village associations to build mosques, schools, and infrastructure such as water towers and electricity in a display of what Daniel Smith calls “conspicuous redistribution” became a mark of having “become somebody” as an adventurer.57

The notion of migration as adventure and the personhood of the adventurer as an alternative to the abject refugee or the subjugated wage laborer offers a compelling counternarrative to state policies aimed at controlling and defining migration and migrants. Migration, in this tradition, is not a problem to be solved but a mechanism for social and economic reproduction; it is not only a choice made to combat poverty or dire circumstances, but a pathway toward social becoming.58 As much as it has changed over time, the notion of adventure serves as a hermeneutic, guide, and moral beacon for West Africans abroad, a lighthouse that they seek in times of trouble.59 From the perspective of adventure, migrants are embedded in a social system in which confronting risk through the migratory journey helps—not hinders—their transition to adulthood. From the perspective of adventure, migrants are not seeking settlement, citizenship, and dependence but rather the conditions of possibility for continued mobility and exploration.

LASSANA’S PATH

Lassana was fourteen when he began making plans to leave his home. The following year, unbeknownst to his family, he jumped onto a truck and went from village to village doing odd jobs until he made his way to Bamako, the Malian capital. His father sent his brother to get Lassana to return. Instead, Lassana refused, saved up more money, and left for Côte d’Ivoire. This dramatic and secretive escape from the clutches of parental and elder sibling authority, as he tells the story, set the stage for his ensuing adventure across West Africa and into France.

He had grown up in a village I will call Yillekunda, ten kilometers from the town of Diema in the region of Kayes, the largest sending region of Malian immigrants to France. He grew up in a multiethnic and multilinguistic environment dominated by Soninke speakers. The village depended on millet and other grain harvests from collectively owned agricultural land as well as on remittances from migrants abroad, and it had experienced severe droughts in the 1970s and 1980s. As in other parts of the Senegal River Valley, his village was plagued by a lack of access to water for irrigation, as well as a lack of state presence and infrastructure.60

Lassana’s family was part of the ruling elite in a village divided between “nobles” and those in professional castes (such as blacksmiths).61 He was the first son of his father’s second wife and had three older step-brothers (the children of his father’s first wife). Lassana’s position within his family would have several consequences for the trajectory his life took. As the son of a second wife, he had to do the bidding of his half-brothers and accept the beatings he got from them without complaint. His mother died when he was ten years old and his older sister left to marry a Malian living in France, leaving him and his younger brother alone to fend for themselves against them. There was a public school with instruction in French located near his village, but like most of his brothers who would be leaving on adventure, Lassana attended Qur’anic school. Qur’anic school, according to his father, would prepare them for a difficult and disciplined life on the road and help them to stay on the right path of Islam while abroad.

Lassana’s departure on the truck signified his leaving of the world of lineage and his entrée into the liminal world of adventure. Far from being outside the bounds of kin reciprocity, however, he relied on help and finance from family members while on the road. Once successful, he would have to help kin with their migratory projects. Leaving has become an expensive business, entailing high fees for identification documents, visas, and travel tickets or large sums paid to traffickers. While some families may save money to help fund migration, it is often kin abroad who have the capital to help their family members depart.

To get out of West Africa, Lassana needed a national ID card, for which he would have to pretend to be over eighteen. Bamako, he intimated, was not distant enough to be part of a “true adventure,” and he knew he had to move on or risk being sent back to his family. He worked odd jobs for Soninke cousins until he had enough to go to Abidjan. Lassana stayed in Côte d’Ivoire, moving to Daloa, a center of the cacao trade, until he saved enough money to get a passport and apply for a merchant visa that would grant him a temporary stay in France. He had proved himself on the road, and when he was eighteen, he got his father’s blessing for the trip to France. He returned to Bamako to get his papers in order.

His father, who had ventured as far as neighboring Senegal, visited him there and taught him the secret rituals he had to practice once in Europe to avoid misfortune. His older sister in France sent him a plane ticket. He did not go back to Yillekunda before he left for Europe. Returning home would have been anathema when his adventure had barely begun. In 2001, he boarded an Air France flight with a three-month visa, imagining that he would stay for two or three years and then move on or return to Mali. He would not leave France for almost a decade.

MAP 1. The West African home region of many adventurers at the station, showing the route Lassana took from Yillekunda to Abidjan before coming to France. Thomas Massin.

Tunga te danbe don, nga a be den nyuman don: this is the Bamanakan (Bambara) proverb of the adventure, which anthropologist Bruce Whitehouse argues is key to understanding West African migrants and which he translates as: Exile knows no dignity, but it knows a good child.62 Or in other words, as Lassana’s friend Dembele put it, “When you’re an aventurier, you’re nobody.” An almost identical proverb exists in Soninke: Tunwa nta danben tu, a na len siren ya tu, which Soninke linguist Abdoulaye Sow translates as “Our identity can be ignored in foreign lands, but not our courage.”63 Migrants leave their home and go into a new world where the status they grew up with (their lineage-based identity/dignity) means very little; what matters is their own hard work. This is why, as Whitehouse points out, they can take jobs that would otherwise be shameful. The proverb is a poetic concentration of the adventurer’s liminal logic, and of the notion that when they leave en aventure they leave the constraints of village structures behind. But their activities at the Gare du Nord suggest that they do seek both dignity and respect—not only jobs and material resources—through their time there. They hope to recover the masculine status and dignity denied by the police, their legal status, and their jobs. In this context, they suggest a new version of the proverb: Exile that lasts for decades may yet know dignity, if you have courage.

DWELLING IN MOTION

Most West African adventurers in France do not end up at the Gare du Nord, and given its reputation for attracting criminals and delinquents, many even look down at their brethren who do. Those who invest in the station are seeking a pathway to success and social relationships outside the scripts of French assimilation and kin expectations. By focusing their efforts on the Gare du Nord, they cultivate an alternative version of integration into French public space. They sought to meet passengers coming from afar on high-speed trains and to form friendships with other adventurers. As in the social clubs (grins) of urban West Africa, they were not brothers but equals who met to chat and drink tea, sometimes developing strong social obligations of solidarity.64 Lassana and his peers even developed a particular way of interacting with the police. Their practices—whether economic, social, romantic, or a combination of all of those—involved making connections across the station’s many social boundaries, and their strategies stressed the importance of building horizontal networks and relationships more than they focused on gaining the rights of citizenship from the French state.

Those horizontal relationships and networks suggest that integration (contrary to French rhetoric on the subject) is not opposed to community, mobility, and ties to elsewhere. Adventurers at the Gare du Nord delve into French urban life—at the center, not on the sidelines—because they believe that full experience abroad is what will allow for self-realization and for the reproduction of their agrarian communities. The notion of settlement as a goal does not make sense to them; meaningful integration instead ought to create opportunities for mobility and personal growth. They are not simply “economic migrants”; they are also explorers seeking knowledge in faraway lands.

What if, adventurers ask, integration did not entail settlement? Could there be a more just model of integration based on a more mobile worldview? Instead of thinking through migration from the endpoint of settlement, we might instead see it through what Catherine Besteman calls “emplacement”—the many ways that migrants experience and engage with places where they live. Emplacement here is a form of belonging that diverges from the official paths of assimilation offered by state programs and laws.65 Through emplacement, migrants form communities and make their mark on their dwelling places, which can also become important loci of political claim-making.66 Unlike neighborhoods and immigrant dormitories, emplacement at the Gare du Nord has a direct connection with mobility. Emplacement in this context engages with transportation infrastructure—the channels and pathways that meet at the station. By staying put and practicing emplacement in a space meant for circulation, adventurers also challenge the prevailing logic of how the station is managed and policed. They dwell there, create networks, and try to produce value, but they do not settle. This dwelling-in-motion is rich in narrative: adventure stories are told and retold at the station, and become circulating tales that provoke debate and discussion over how migrants in France ought to act, work, and respond to hardship. By tracing adventurer strategies and pathways at the Gare du Nord, I examine how migrants make emplacement and mutual belonging through a public space designed for transience and anonymity.67

MOBILITY AND FIELDWORK

My work with adventurers like Lassana and many of his friends whom I met during the years I spent researching pushed me to look beyond the media spectacles surrounding the station in the 2000s and to consider the longer history of the Gare du Nord. To understand their lives and what drew them to the station, I had to understand this complex space that hundreds of thousands of people passed through each day, a space whose history as France’s largest international train station offered a crucial window into ways that ideas about racial and cultural difference had been built into French public spaces.

Carrying out an ethnography of a major transportation hub has some methodological challenges, and I experimented with approaches from urban studies, anthropology, cultural history, and geography. I needed some guiding lights of my own as I joined adventurers at the station. The corpus of urban anthropologist Setha Low offered a multifaceted approach to doing ethnography in complex public spaces, and Low illustrates how to balance political economic critique without losing the texture of lived experience and emotional attachments.68

Paul Stoller’s ethnography of West African traders, Money Has No Smell: The Africanization of New York City has provided a model of what the transnational ethnography of migrant experience in urban space can contribute to our understanding of global economic transformations. Focusing on the trajectories of a small number of migrants reveals, as Stoller puts it, “how macrosociological forces twist and turn the economic and emotional lives of real people.”69 I build on Stoller’s approach by examining the longer history of the Gare du Nord, seeing this site as a prism reflecting not only the migrant experience but also state projects of ordering and policing difference. The station itself offers the methodological object from which I have built this ethnography outward to answer the question: What does migration, urban space, and integration look like from the view from the tracks, from the perspective of the Gare du Nord?

The second inspiration is Lassana himself, his story, and his commitment to this project. I have tried to do justice to his story and analysis, in the process documenting how an adventurer confronts the precarious realities of contemporary migration while negotiating his own coming of age. This approach recalls the life history method, well established in African studies, that privileges narrative depth in order to show how individuals imagine and build their worlds under a set of historical conditions and constraints.70 The innovative work on life course by anthropologists Jennifer Cole and George Meiu (among others) offers a framework to consider the continued importance of social and kin relations in changing conditions.71 In following Lassana’s adventure, I also take my methodological cue from West African modes of imagining life pathways, where aspirations for living a dignified life in tough circumstances lead to the invention of new strategies.72

Adventure Capital is based on eighteen months of intensive fieldwork in Paris between 2009 and 2011, as well as several visits between 2012 and 2018 that allowed me to follow up with the people I worked with and track changes at the station. As Peter Redfield observed, ethnographers often have more in common with Claude Levi-Strauss’s bricoleur than with the engineer: fieldwork unfolds through improvisation with available materials rather than via engineered design.73 “The subway corridors,” Marc Augé suggests in In the Metro, “ought to provide a good ‘turf’ for the apprentice ethnologist,” but only if she dispenses with classical methods of interview and survey, and instead is able to observe, follow, and listen.74 I followed these improvisational approaches as I traced the many threads that led to and from the station, going where they took me instead of defining a particular (national or ethnic) group in advance. Ethnographers can learn from adventurers, as I did. I became an apprentice to the Gare du Nord method—learning to use encounters across difference to build networks and create value in a transit hub. They taught me to observe people, to discern what encounters were worthwhile, and to make new channels connecting places, displacing commonsense ways of seeing the world. They stress the importance of knowing the past from several angles, and were invested in uncovering the history of the Gare du Nord. To this end, I examined tribunal records and blueprints from the Paris Municipal Archives, North Railway Company correspondence and meeting minutes from the National Labor Archives, and blueprints and directives from Haussmann-led Paris in the National Archives.

I spent most of my fieldwork hanging out around the station and talking to a changing group of about thirty-five West African men who ranged in age from nineteen to thirty-two, and who strolled, talked, sat, and observed together in the front square and in cafés around the neighborhood. Most of these men had been in France between three and twelve years, and about half of them were undocumented, while most of the others had recently obtained resident permits. The majority came from the western Kayes region of Mali and its adjoining areas across the borders in Senegal and Mauritania, while a few others came from Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea. They spoke a mix of French, Pulaar, and several Mande languages (Soninke, Jula, Bamanakan, and Khassonke) among themselves. Almost all identified as practicing Muslims and, with the exception of the Ivoirians, they had attended Qur’anic schools and did not speak French when they arrived. They worked in subcontracted and temporary labor jobs in construction, cleaning, and food service. In the summer of 2010, I spent two months as an SNCF intern on the high-speed lines, and accompanied railway police on their patrols, offering another perspective of what it meant to see through the lens of the Gare du Nord, and to understand how adventurers were represented and imagined by station workers.

A few caveats: The population of a major city passes through the Gare du Nord each day, and this book does not attempt to offer a picture of its totality. I made the choice to seek in-depth knowledge in order to offer the “thick description” that distinguishes meaningful ethnography, even in our “multi-sited” age of mobility.75 Most of the subjects in this book are West African men, in part because French policies and policing have a particular impact on them.76 Like the adventurers documented here, West African women are also struggling to make their own pathways toward integration—just not through the Gare du Nord.77 I also sought to explore the way that West Africans adventurers see and create a world in the station. This called for time and resources to explore all facets of their lives, including in some cases going back to their villages and meeting their families. It was after I returned from Mali and Senegal that I began to understand what was happening at the station.

I did not have the resources to do this in-depth work with all the people and worlds of the station; the book is focused on adventurers and the networks they made. It bears pointing out that although they are often represented as “Africans,” adventurers are a diverse group: they are multilingual, multiethnic, and multinational. I also chose not to focus on the people involved in drug dealing or crime: they occupied an outsized place in the media and popular representations of Africans at the station, but few of the men I met there were involved in illegal activities.

Research in a public space where I had no status was challenging. For the first six months of my research, many people believed I was a police officer or informant and denounced me to their peers. I was often yelled at and accused of conspiring with the police. I came to understand that these were attempts to situate me within an unstable universe where a single bad encounter could lead to failed immigration projects, arrest, or deportation. As in much ethnography, a “key informant” enabled my provisional integration into the station social scene. Lassana took me under his wing as a social apprentice, vouched for me, and became my de facto field research assistant (a role for which he refused to accept money). In the moments when I became dejected with the feeling that I would barely scratch the surface of what was going on at the station, he would find a new person for me to meet, or a new corner of station life to discover. He knew the place, as he liked to say, like his own hand.

Our relationship illuminated some of the way gender roles played out in this male-dominated social environment. We met because he, like many of his comrades, were using the station to meet women. He approached me to ask for a cigarette—even though he did not smoke. I asked if he would talk to me for my research. He agreed, and ended up acting as my protector, an older brother figure and station guide. This relationship meant that I was rarely hassled at the station, even when he was not present.

My experiences illustrate how constrained women’s roles were at the Gare du Nord: unlike men, women could not hang out and chat—it was assumed they were there to meet men. Any time I sat in a café with Lassana (or anyone else), his friends who came by to say hello and who did not know me asked him in Soninke or Bamanakan whether I was his girlfriend. They were suspicious when he said no and explained that I was writing a book about the station. I did not fit into the categories that women were supposed to occupy. If I was not someone’s girlfriend, they reasoned, I must have been with the police. It was only after I went to the station in 2016 with my son, a baby at the time, that some men I had known for years admitted that up until then, they had suspected I was French and not from the United States, and that I was working with the police. My newfound status as a mother was part of what changed their opinion.

During my research, I took on multiple roles that also helped me to understand the precarious positions these men found themselves in. When they had to find new housing, I became an amateur real estate agent, looking for apartments after assessing their budget and transportation needs. When they legalized their status and decided to make a return visit, I helped them find flights using the internet. I helped edit résumés for temporary construction work and fill out applications for unemployment benefits.

Aside from formal interviews with train station personnel and urban planners, I spent the first year in the field using my tape recorder sparingly. All the men I spoke to knew about my research project and had agreed to take part. I took my cue from other urban anthropologists working among sensitive or marginalized populations and embraced the “unassuming research strategy” of participating in daily life and conversations, and then rushing away to write it all down in a notebook afterward.78 As I built trust among some of the men, I started using my tape recorder or cell phone to record longer narratives and conversations.

Everyone I spoke to knew I was doing research, and many of them were invested in my book project. In the decade since I began, our lives all transformed. Their adventures all turned out differently than they had imagined, and the Gare du Nord could not change the realities of legal, social, and economic marginalization. But it did give them a space to discover “the France you don’t see on TV,” as Lassana put it—which is also what I want to illuminate here.

TRACING BOUNDARIES

The story of the Gare du Nord and the experiences of West African adventurers there are the twin intertwining threads that structure this book. When the station was built in the mid-nineteenth century, it was part of an imperial vision imagining the melding of modern industry, infrastructure, and international exchange. But railway terminals were also feared as threatening spaces of social mixing that needed new measures to separate, control, and police the “dangerous classes” that converged there. Chapter 1, “Dangerous Classes,” considers the Gare’s early days to show how inequality based on ideas of racial difference has been built into this public space, as part of efforts to ensure for smooth transport and circulation while controlling the potential threats to the political and social order of bourgeois Paris. Today, migrants confront the remnants of the station’s guiding imperial ideology as they reconfigure their relationship to the history of public space in Paris.

When part of the Gare du Nord was rebuilt at the dawn of the twenty-first century, it came to embody anew the contradictions between a French Republican narrative of inclusive “living together,” and the policing methods used against people of color at the station. The station’s rebuilding and the 2007 revolt that took place in its wake are the foci of chapter 2, “The Exchange Hub.” After considering how a public space in the center of the capital became a crucible of anti-black racism and French national boundary definition, I examine how African-French young people and West African migrants used the March 2007 station revolt to defy their marginalization and make the station into a meaningful site for political action and social relationships.

The revolt trained the floodlights of the national media on the Gare du Nord and reinforced the discourse that Africans were threatening and dangerous to French public order. But there was nothing exceptional about the racialized police intervention that sparked it. In the everyday life of this transit hub, West African migrants were living out their adventures as they were confronted with new laws and policing practices. Chapter 3, “The Gare du Nord Method,” explores the encounters between migrants and police. As West Africans learn to deal with the police, they also produce new survival strategies, refashion social relationships, and confront their precarious position head-on.

Adventurers engage in many kinds of work at the station, from providing services for train voyagers to building and maintaining social relationships. Chapter 4, “Hacking Infrastructures,” explores how they use the station to expand their economic opportunities by seeking encounters across difference and by transforming state transit infrastructures for their own ends. As they are further marginalized by policy and by diminishing economic opportunities, West Africans use tools and knowledge gained on their adventures in an effort to produce new channels for creating value.

The Gare du Nord method is not only a practical set of tools for dealing with the precariousness of migrant livelihoods, it is also the way that West Africans who claim it attempt to forge a new pathway for their uncertain coming of age. Chapter 5, “The Ends of Adventure,” examines how West African migrants seek self-realization through the station’s social world while maintaining patrilineal and village ties. The station transforms their pathways to adulthood as they connect it to transnational circuits of social reproduction.

I end by considering the outcomes of the Gare du Nord method and speculating on the ways that adventurer visions displace ideologies of difference arising from colonial domination, which exclude African migrants from being seen as part of the European collective project. The Gare du Nord cannot save migrants from marginalization. Nevertheless, migrants work to reproduce a world where adventure is still possible, and in doing so, they offer an alternative pathway toward the ideal of mutual belonging, recognition, and living together.

Adventurers undermine the boundaries—between migrant and citizen, center and periphery, neighbor and stranger—that have come to define political debate and the contours of French public space. West African migrants have pulled the Gare du Nord into networks and relationships that neither the French state nor their own families could have predicted. This book is the story of how that happened and what might happen if we consider the histories of border making and difference, urban space and migration, belonging and exclusion, from the perspective of adventurers at the largest railway hub in Europe.