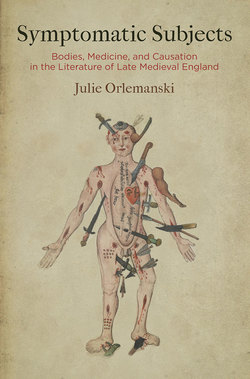

Symptomatic Subjects

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Julie Orlemanski. Symptomatic Subjects

Отрывок из книги

Symptomatic Subjects

Mary Thomas Crane and Henry S. Turner, Series Editors

.....

In this document, then, the practice of bodily interpretation appears in its deeply social aspect. Joanna’s neighbors are the first to diagnose her, drawing on the traditions of sequestration in canon law (and ultimately Mosaic Law) as well as novel rhetorics of contagion.86 It is impossible now to determine the reasons behind this initial diagnosis. Were there visible symptoms that called for it, or was it motivated by the desire to lay hold of a woman’s property, or to bridle her willful behavior? Joanna’s neighbors, finding their diagnosis ignored, petitioned the court of Chancery to lend it legal force. But against the normal course of common law, in which a jury’s judgment was adequate to determine leprosy, the king’s own physicians were solicited. Thanks to the exceptional intervention of Joanna’s apparent ally Robert Stillington, scientific discourse gained a foothold in the situation, and the physicians answered the earlier writ with their own exam, rendering “the truth [veritas] on this subject most plain and clear [clarissima].”87 None of the documents includes Joanna’s own account, but her refusal to accede to her neighbors’ diagnosis is a statement in itself. Though the patient’s speech is given no particular authority in the document, it is her diagnostic dissent that gathers a conflicting set of interpretive practices around her. The situation illustrates how the parsing of bodily signs was the occasion not only for interpretation but also for the extrasemiotic negotiation among different authorities and systems of bodily discernment.

Physiognomy, like leprosy’s diagnosis, occasioned the fraught recoding of medieval bodies into legible signs. The physiognomic art sought to discover a person’s character on the basis of bodily features, and in late medieval England it circulated in the discursive borderlands between medicine, natural philosophy, magic, and literary pleasure. Like phisik, physiognomy derives from the Greek term physis. As one Middle English treatise remarks, “This word phisonomea ys said of phisis, that is nature, and gnomos, that is dyvynynge [divining, discerning].”88 In his influential commentary Roger Bacon (d. 1294) gave the word a slightly different gloss: “‘Physiognomy’ is the rule of nature in the complexion of the human body and in its composition—because in Greek ‘nomos’ is ‘law,’ and ‘phisis’ is ‘nature’ [Phisonomia est lex nature in complexione humani corporis et eius composicione, quia Grece ‘nomos’ est ‘lex,’ ‘phisis’ est ‘natura’].”89 Whether grounded in gnosis or nomos, medieval physiognomy presumed the ordered lawfulness of nature, which undergirded the correspondence of physical features and character. This mutual entailment of body and behavior was usually explained with a nod to astrology. James Yonge, in his translation and redaction of the Secretum Secretorum in 1422, states that “al bodely thyngis [all bodily things] be governyd and ordaynyd by the Planetes and the Sterris [stars],” and accordingly everyone is “disposid dyversly [diversely] to vertues and to vices.”90 Astral determinism does not sit comfortably with Christian theology, and Étienne Tempier’s well-known condemnations of 1277 insisted anew that stars merely incline and do not determine human behavior. But physiognomy leaned heavily on this inclination and elaborated the fantasy that bodies, by virtue of being natural things, made persons legible.

.....