Читать книгу Symptomatic Subjects - Julie Orlemanski - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Imagining Etiology

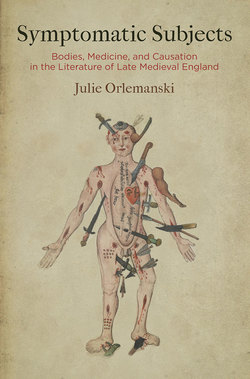

On the final decorated folio of a fifteenth-century English medical manuscript, a figure gazes out. This is the Wound Man, a conventional surgical diagram that has been rendered here, in what is now London, Wellcome Library MS 290, with extraordinary delicacy (Figure 1).1 His well-proportioned body stands with a naturalistic grace, left leg slightly bent, even though the outline of his body is punctured with arrows, swords, clubs, and spears, and his skin gapes with open sores. He regards his viewers calmly from this unbearable embodiment, displaying his gashes and lesions. The picture is the last in a series of eight full-page medical illustrations in the manuscript, occupying their own quire after a pair of anatomical treatises in Middle English.2 The minute strokes of the artist’s shading evoke the heft of the Wound Man’s limbs and testify to a degree of mimetic craftsmanship in excess of the image’s technical purpose. Like the medical diagrams of the Disease Man, the Blood-Letting Man, and the Zodiac Man, the Wound Man is designed for heuristic reference, not verisimilar representation; he gives schematic and mnemonic shape to a long list of cutaneous conditions. But in this manuscript, unusually, the image has little connection to the accompanying medical texts, and the Latin labels that unfurl around him are not linked to further elaborations.3 He is unmoored from any straightforward purpose. The floating tools and weapons around him suggest the instruments of the arma Christi, the oft-depicted instruments of the Passion, and even more closely he echoes warnings against Sabbath breakers found in medieval English wall paintings, where images of the “Sunday Christ” show implements biting into Christ’s limbs just as they do into the Wound Man’s.4 Finely detailed features, his closed lips and heavy-lidded eyes, intimate a sense of lucid endurance and, together with this, the impression of inwardness, some self that is the locus of his undergoing. Whatever depths are hinted at, however, recede from the shallow openness of his chest cavity and the Wound Man’s bright, bared heart.

Figure 1. Wound Man. English, late fifteenth century, Wellcome Library MS 290, fol. 53v. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London.

Untethered from texts describing treatment for his injuries, then, the Wellcome Wound Man is at least as much about the emotional and aesthetic pull of his injured figure as he is about surgical expertise.5 Like many of the corporealized figures discussed in the chapters to follow, he conjures a multitude of discourses and associations. The contents of the manuscript bespeak theoretical anatomy; his iconography’s origins are in surgical therapeutics; and the parallels with Christian devotional imagery are too obvious to be missed. But he also signifies in terms less bound by discursive context. Insofar as medicine addresses broadly shared conditions like pain, mortality, and physical flourishing, the line between technical expertise and palpable experience is never secure. The Wound Man, with his finely modeled limbs and face, exerts a mimetic and thus a recognitive claim. He is like us—and that intuition is perceptible in the minor discomfort of calling him an it. At the same time, this is unambiguously a diagram, a pigmented shape. Medical knowledge depends on the abstraction and inscription of corporeality, and the ontological gap between representation and flesh ongoingly qualifies interpretation. Between him and it, the Wound Man holds viewers’ gaze in the image’s crosscurrents.

Because the significance of the human body is never strictly scientific—because it attracts multiple schemes of regulation and recognition and calls up notions of experience, consciousness, and self—situations of medical explanation verge constantly into dramas of embodiment and expression, interpretation and feeling. This chapter and those that follow attend to such dramas as they unfolded in the era of medical writing’s popularization in England. Wellcome Library MS 290 is a small part of what was a sea change in how men and women in medieval England read and wrote about their bodies. During the later fourteenth century and throughout the fifteenth, medical textuality flourished. English readers demanded and produced an enormous number of manuscripts addressing why bodies thrived and suffered and how they could be healed. The spread of medical literacy called for imagination as well as intellectual and practical skills. It asked audiences to picture their bodies, their world, and the interactions between them differently. Readers experimented with seeing themselves medically and seeing their bodies as the materialization of causes. Optimistically, medical textuality helped to realize a causally labile universe, one in which readers might understand and influence their corporeal conditions. More darkly, medicine articulated the constitutive vulnerability of the microcosm to the macrocosm—a vulnerability figured in the Wound Man’s opened flesh.

The Wellcome Wound Man acts as something of a found allegorical figure, embodying dynamics that are at play across the length of Symptomatic Subjects. In the simultaneity of his woundable passivity and his upright carriage, he brings to a point of high tension the qualities of determination and agency that recur in medieval depictions of symptomatic expression. By seeming to show his wounds, to relate himself to them in the midst of his hyperbolic suffering, he suggests the centripetal pull of the self as an idea that gathers the porous, dissolving body back together. The Wound Man is also a crossroads for narrative. Each of his particular harms—incisio cerebri (incision to the brain), inflatio faciei (swelling of the face), sagitta cuius ferrum remansit in carne (arrowhead stuck in the flesh)—unspools an incipient case history. Finally, what turns out to be his melancholy joke is that he is no one. He portrays no singular body, not even an idealized one. The extravagance of his injuries is a function of his generality: he condenses in one figure what medical practitioners would have encountered across dozens of patients. Medieval theories of knowledge, which were shaped by Aristotelian thought, held that there could be no true science of particulars. Accordingly, the translation from individual patient to general rule and back again was required for the understanding that phisik made possible. But it is the Wound Man’s wit and pathos that he at once embodies and evades that translation. He sets generality in the teeth of individuation, so that it is hard not to see him, this compendium of maladies, as an ill-fated and piteous fellow.

The present chapter explores some of the dynamics exemplified in the Wellcome Wound Man, which are also endemic to the interpretation of bodies in late medieval England. The Wound Man personifies these dynamics in a decidedly extreme form, on the edge of paradox. However, as will become clear, the strange conditions of the Wound Man’s flesh—the polarized interplay of determination and agency, the embodiment of causes, and the flickering between generality and particularity—can be traced through much of medieval medicine and other endeavors of somatic interpretation in the period, as they helped set in motion novel projects of explanation, expression, and imagination.

Symptoms and Selves

Among the pilgrims described in the General Prologue of the Canterbury Tales, it is Chaucer’s Summoner who is least at home in his own skin. No doubt, the man has his physical pleasures: he loves eating garlic, onions, and leeks, drinking strong red wine, belting out a duet with the Pardoner in his “stif burdoun [strong bass],” and enjoying the company of “his concubyn,” not to mention the other “yonge girles of the diocise.”6 But the Summoner’s portrait begins with his irritated, abraded, and discomfiting face and all the remedies that fail to change it:

A Somonour was ther with us in that place,

That hadde a fyr-reed cherubynnes face,

For saucefleem he was, with eyen narwe.

As hoot he was and lecherous as a sparwe,

With scalled browes blake and piled berd.

Of his visage children were aferd.

Ther nas quyk-silver, lytarge, ne brymstoon,

Boras, ceruce, ne oille of tartre noon,

Ne oynement that wolde clense and byte,

That hym myghte helpen of his whelkes white,

Nor of the knobbes sittynge on his chekes. (623–33)

[A Summoner was with us there, who had a fire-red cherubim’s face and narrow eyes, for he was afflicted with saucefleme. He was as hot and lecherous as a sparrow, with scabby brows and a patchy beard. Children were afraid of his appearance. No quicksilver, lead oxide, brimstone, borax, white lead, cream of tartar, nor any ointment that cleans and burns might help him with his white pustules, nor the knobs sitting on his cheeks.]

Saucefleme—salsum flegma or “salt phlegm”—was an itchy, scabby inflammation of the face, which entailed swelling, discoloration, and pustules. It could be a symptom of leprosy but was generally regarded as a dermatological ailment in its own right. That the term is unusual in the late fourteenth century is suggested by the fact that the General Prologue is the earliest recorded usage, with nearly all subsequent attestations coming from remedy collections or surgical treatises.7 The word’s technical flavor marks the Summoner’s individuating details as notably medical phenomena. The diagnostic quality of readers’ attention is bolstered by the lines’ implication of causal links between the Summoner’s intemperate behavior and his pathology. Numerous scholars have catalogued the echoes between the portrait and medieval medical writings.8 Yet even if some of Chaucer’s contemporary readers were uninformed about the details of phisik, the similarity between the Summoner’s “fyr-reed” visage and the “strong wyn, reed as blood” and the rhyme between his pimpled “chekes” and diet of “lekes” would insinuate correlations between what the Summoner does and what he physically is (624, 635, 633–34).

By the point that the Summoner appears in the General Prologue, Chaucer’s readers have grown familiar with their hermeneutic task—to glean from details of dress, habit, physiognomy, and diction hints of each pilgrim’s moral disposition and style of social inhabitation. The momentary encounter, we are given to understand, is a metonym for the greater life, and each visible exterior ciphers a distinctive personality. So, the Yeoman’s “broun visage” reflects his life outdoors, and the Prioress’s vast “fair forheed” imports courtly mien (109, 154). That the Monk is “ful fat” is not unrelated to his appetite for “fat swan” (200, 206), and so on. The General Prologue is one of the great documents of characterological implication in medieval literature, and features like the Miller’s wart and the Cook’s mormal have primed readers to conjecture among behavior, persona, and bodily form. As the audience looks through the narrator’s eyes, they exercise a symptomizing regard, discovering in each pilgrim’s appearance traces of those forces—institutional, natural, and subjective—that shape the life. Diagnosis and etiological imagination mingle with the everyday business of social discernment.

When the narrator reports of the Summoner, “saucefleem he was, with eyen narwe. / As hoot he was and lecherous as a sparwe,” the lines’ three characterizing adjectives (saucefleem, hoot, and lecherous) all point, from different angles, toward the mediating notion of complexio. Complexion—the relative calibration of the body’s four primary physical qualities (hot, cold, moist, and dry) and its humors (phlegm, blood, black bile, and red or yellow bile)—was perhaps the most widely known idea from Galenic medicine in the Middle Ages. Complexional theory acted as a rational basis for linking together the body’s circumstances, its state of health, its appearance, and its unseen material reality. Understood in terms of complexion, saucefleem represents an imbalance in the humors. Disease in the Middle Ages was conceived not in terms of an underlying invasive entity but as temperamental disequilibrium. The idea that the Summoner’s dietary and sexual excess is somehow responsible for his saucefleem partakes of the understanding of complexio as a proportionality that varies constantly, fluctuating with every change in someone’s intake, environs, and behavior.

The adjective hoot, by contrast, hints at a more permanent physiological condition. As Nancy Siraisi explains, in medieval medical theory “each person was endowed with his or her own innate complexion; this was an essential identifying characteristic acquired at the moment of conception and in some way persisting throughout life.… Thus, a particular person might be characterized as having a hot complexion relative to other human beings, and this characterization would apply to him or her throughout life.”9 Such categories became sweeping social typologies in the later Middle Ages, as their use elsewhere in the General Prologue suggests: the Reeve is “a sclendre colerik man,” while the Franklin’s “complexioun” is “sangwyn” (587, 333). In these cases, the order of causation partly reverses itself: it may be because the Summoner is “hot” that he craves what he craves and does what he does. Complexion produces action, as well as action producing complexion. Lecherous shifts the Summoner’s description more squarely into the moral realm, though the disposition to lust too could be entailed by humoral disposition. The comparison to a sparrow reinforces the apparent innateness of the Summoner’s characteristics. The sparrow “is a ful hoot bridde and lecherous,” reads John Trevisa’s translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus’s popular encyclopedia De proprietatibus rerum.10 How different are the sparrow’s species traits from the Summoner’s proclivities? Does the man’s complexion determine him, or does he determine it? Would physiological and moral change demand an Archimedean point beyond the confines of the Summoner’s own flesh?

In no way does the General Prologue force such questions, which after all were among the most contentious of the Middle Ages and edged swiftly into disputes about inclination and free will.11 It is part of the narrator’s blithe tact not to dwell on matters like these. Tensions between choice and disposition, or between individual and type, are allowed to remain suspended, and in this way Chaucer’s General Prologue is similar to the medical discourse that partly undergirds it. Both phisik and Chaucer-the-pilgrim leave aside dogmatic pronouncements to concentrate on the intricately particularized individuals at hand. But in the process of doing so they end up instantiating a distinctive way of seeing the world, focused on persons’ jointly material and semiotic constitutions and how these constitutions might be read.

The co-implication of natural impulse and human action is raised in no less prominent a place than the first lines of the General Prologue. It is “Whan that Aprill” moves the nectar in the flowers and sets the mechanisms of spring into lush operation, “Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.” The temporal coincidence of season and devotion allows nature and religion to share the stage, and the mischievous rhyme between the songbirds’ corages (where they feel Nature’s prick) and the people’s pilgrimages needles a connection that remains unsettled and unsettling throughout the Canterbury Tales, namely, the link between what we are (our longings, our actions, our bodies, our identities) and the forces in which we are enmeshed, like the prickling warmth of April and our answering flesh. These are the relations, between conditions and causes, that medieval medicine addresses as well. The more that readers of the General Prologue wish to pin down a given character—to diagnose the Summoner, interpret the Wife’s gapped teeth, determine whether or not the Physician is blameworthy, or know if the Pardoner is “a geldyng or a mare” (691)—the more urgently do uncertainties about causation, agency, and the stability of signs circulate. But the breezy narration, like complexio’s manifestly flexible apparatus, keeps radical incoherence out of sight. Both the General Prologue and medieval physiological theory generate a sense of knowing that trails off in the details, leaving room for indeterminacy. In Chaucer’s hands, this trailing off nourishes the impression that each pilgrim has a subjectivity in excess of the available grids of explanation.12 He invites his readers, then, to follow the advice of Galen (d. c. 210 CE), who declares that interiority can be known “if not by means of an absolutely firm kind of knowledge [disciplinam certam], then at least by ‘artful’ conjecture [secundum coniecturam quandam artificialem].”13

Throughout this book, I use the term symptom to name a somatic disturbance that, in its departure from expectations of bodily appearance or function, provokes interpretation. Symptoms appear when we regard bodies as animated systems of signs that refer to the nonconscious or only partly conscious processes in which material selves are entangled. Symptoms need not be medical. Miraculous indices of God’s favor appear frequently on medieval bodies, and romances are full of characters whose bodies mutely testify to their noble origins, like the light pouring from the mouth of Havelock the Dane. For their construal, symptoms require not only that interpreters work back from effects to cause but also that they make a decision among explanatory systems. Hermeneutic instructions are not in symptoms—not in the body’s pallor, excretions, pulse, or pain—but rather in the discursive environment where the body is embedded and becomes legible. The General Prologue pulls readers through a shifting series of discourses—moralistic, satirical, courtly, penitential, exemplary, physiognomic—to interpret the pilgrims’ figures. In the Summoner’s portrait and the “artful conjectures” it inspires, medicine’s primary operations of diagnosis, etiology, and treatment blend seamlessly into the structuring themes of the General Prologue, like the tensions between natural impulse and human action, type and individual, and sign and self.

My broad definition of the symptom, as an involuntary bodily sign, is at odds with the word’s narrow use in medieval Latin (symptoma, sinthoma) and in Middle English (sinthome), where it almost always appears in the context of learned medicine.14 The ancient Greek term originally meant a mischance, something that happens to or befalls someone, and it is relatively late in the development of Greek medical writing that sumptōmata came to denominate those bodily phenomena from which disease is inferred.15 In the twelfth century a transliterated form of the Greek word made its way into Latin translations of classical medical writings, to denote a quality or condition of the body—as in the Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum, or the “Book on the Conditions of Women,” as Monica Green translates it.16 From Latin, the word eventually entered medical writing in Middle English. More often, medical writers and translators employed the terms accidens (in Middle English, accident) and significatio (signe or token) to name the indices of disease. “Accident” forms a neat etymological counterpart to the Greek sumptōmata: from ad and cadere, it also means a falling to, or something that befalls, which gives it its philosophical sense as a contingent attribute.

Medieval theories of the natural sign (signa naturalia) are one framework for understanding the symptom’s yoking of causation and signification. According to Augustine’s foundational De doctrina christiana, the division between natural signs and conventional signs (signa data) is a basic distinction of semiotic theory. Whereas words proceed from a desire to communicate via a mutually recognized system of signs, signa naturalia make something known “without a wish or any urge to signify [sine voluntate atque ullo appetitu significandi].”17 Augustine’s examples are smoke, an animal footprint, and the face of someone angry or sad. Smoke “means” fire because smoke is caused by fire; the face indicates the mind’s feelings independently of the will (etiam nulla ejus voluntate).18 Relations of signifier and signified map onto relations of effect and cause. Augustine acknowledges briefly that such signifying is not itself merely natural; it depends on someone’s “observation and memory of experience with things [rerum expertarum animadversione et notatione].”19 Roger Bacon, in his 1267 treatise De signis, elaborates on this point. Bacon was one of the leading interpreters of the “new” Aristotle and a controversially original thinker in natural philosophy. In De signis, he notes that “according to the order of nature [ordinem naturae] one thing is the cause of another without having a relation of themselves to a knowing power, but solely from the fact of their relation with one another.”20 In other words, causes produce effects regardless of whether anyone knows about them. But signification works differently: “By contrast, the relations of sign, of signified, and of the one to whom signification occurs are applied through a relation to the mind apprehending [animam apprehendentem].”21 Despite the symptom’s natural, causal entailment, its legibility depends on learned systems of signs. For accidens to become significatio, the “mind apprehending” must track its meaning.

One of the foundational texts of medieval medical study, the Isagoge of Joannitius (Hunayn ibn Ishaq, d. 873), illustrates how the gap between causation and signification comes to be charged with social import. In its discussion of different categories of symptoms (de generibus significationum), it makes one distinction that depends not on the signs’ bodily location or timing but rather on the vantage from which the symptoms are perceived. “There is a distinction between signs and accidents,” the treatise states, even though “they have a single physical appearance”—namely, “to the patient [infirmo] these are accidents [accidentia], while to the doctor [medico], they are signs [significationes].”22 The same corporeal phenomena—sweating, racing pulse, trembling lips—are here endowed with two different states of existence, depending on whether they appear to the physician or the sick person. The treatise subtracts the semiotic quality of the symptom insofar as it happens to the patient. By reserving the symptom’s signifying power to the medicus, the Isagoge testifies to its place in a self-consciously learned tradition of healing, where interpretive authority rests with the educated practitioner. The distinction of sign from accident, even though “they have a single physical appearance,” also opens on to a much broader issue, namely, what authority (if any) the person bearing a symptom has to interpret it. Does the immediacy of her perspective yield any special insight, or is it disqualifyingly close? How does first-person knowledge rate alongside systematized expertise? Questions like these, about embodied experience and medical authority, are negotiated in many of the texts discussed in the chapters to follow.

It is the symptom’s medium, the living body, that gives the semiotic category its distinctiveness.23 Consciousness has only dim awareness of the biological processes that support its existence—the thickening of mucus membranes, the secretions of glands, the regulation of the heartbeat, and so on—processes that during the Middle Ages were categorized under the body’s “natural” and “vital” powers. Usually these processes carry on beneath the level of direct awareness, but in illness they spring to notice. Pain and bodily malfunction exaggerate the felt distinction between one’s sense of self and one’s corporeality, lending the body a kind of aggression: my stomach hurts; my stomach hurts me.24 In a sermon from the early fifth century, Augustine captures something of this phenomenological insight when he seeks to define illness’s opposite, health. “What is health?” he asks and answers, “Sensing, feeling nothing.”25 He continues, clarifying: “It isn’t just not to feel, as a stone doesn’t feel, as a tree doesn’t feel, as a corpse doesn’t feel; but to live in the body and to feel nothing of its being a burden, that’s what being healthy is.”26 In health, according to Augustine’s account, the body fades from concern, in what for him is a faint foretaste of resurrection. By contrast, symptoms, in their disturbance of somatic operation, trouble the body’s easy absorption into the self and insist that we feel its burden.

Strikingly, as the sermon continues, Augustine links the body’s obtrusion in sickness to the alien quality of medical discourse:

Indeed, we have many things inside us, in our entrails; would any of us know about them unless we had seen them in butchered bodies? Our guts, our innards, which are called intestines, how do we know about them? And then, precisely, it’s good, when we don’t feel them. When we don’t feel them, after all, when we are unaware of them, is when we are healthy. You say to someone, “Observe the esophagus.” He answers you, “What’s the esophagus?” Lucky ignorance! He doesn’t know where he keeps what is always healthy. If it wasn’t healthy, he would feel it; if he could feel it, he would be aware of it, and not for his own good.27

Here the very strangeness of medicine’s perspective and jargon is made into a premonition of suffering. Physiological vocabulary speaks for parts thrust into awareness by discomfort and breakdown. Augustine’s remarks dramatize how illness’s felt disjunction between body and self functions as an opening for discourse, when medicine’s language and gaze find their way into self-perception. To imagine our insides, according to Augustine, we project the sight of corpses inside ourselves, mingling our most private sensations with the observation of dead flesh. The passage’s brief imagined dialogue—Observe the esophagus. What’s the esophagus?—emphasizes the difference that perspective makes in speaking about the body. The terms of physiology seem alien to the healthy man; they name what he does not even know he has. But if he falls ill, he will need to speak in medicine’s idiom. On Augustine’s account, then, first-person experiences of sickness estrange us from our bodies and drive us to find new languages to describe them, to come to terms with what he calls the body’s burden.

None of this is to imply, however, that the Middle Ages had a dualistic conception of body and self. Christian theology and natural philosophy insisted on the ultimately embodied nature of human identity, albeit from different angles.28 Scholastic Aristotelianism taught that the soul was the substantial form of the body, and the incarnational theology central to late medieval devotion foregrounded the inextricability of flesh and salvation. But medieval culture, with its many ways of articulating corporeality, simultaneously spoke about what could not be directly identified with the body—self, subject, soul, spirit, person, reason, will. Through myriad explanations and practices, such terms were then re-related to the self’s materiality. Embodied subjectivity was negotiated between physical determination and willful agency and among the many historically specific ways of describing that interplay.

Returning to Chaucer’s Summoner, we can see that he exemplifies a number of key aspects of what it’s like to inhabit and respond to the observable disturbances of the flesh. Symptoms, as the Summoner’s portrait shows, are both material and social, taking shape between physiology and the expectations that frame it. His face is symptomatic because it is scabby and fyr-reed but also because of the fear that children express when they see it. As readers make their way through his portrait, his anomalous body catalyzes etiological speculation. Details of his life are drawn centripetally around his swollen, carbuncled features. We are called to fit his symptoms into a network of causes running both inside and outside his body and through various moments of biographical time. Etiological inference, it seems, is good at establishing correspondences between body and world but less adept at deciding the priority of cause and effect, or determining the relative fixedness, or fluidity, of embodied identity. And so, symptoms pose riddles of agency. They cannot be controlled merely by someone’s intending: the Summoner cannot directly will his skin fair or his complexion balanced. But symptoms respond to altered circumstances, to changed behaviors and habits. Phisik offers a backdoor to agency, through the manipulation of bodily causes, though in the case of the Summoner’s pharmaceutical self-fashioning, the seven medicines mentioned in the portrait all fall short.

These would-be remedies of quicksilver, lead oxide, brimstone, borax, white lead, and cream of tartar are all topical treatments to be applied to the skin. The superficial nature of the cures is of a piece with the Summoner’s preference for shallow pleasures over spiritual depths and for easy fixes over moral labor. But the remedies’ topicality may also say something meaningful about how the Summoner addresses himself to his body. It is from the outside that he tries to fix his symptomatic visage—from the same vantage that the gawking children aferd of his face look at him and, for that matter, from the position of the appraising narrator and readers. Like Augustine’s account of how someone comes to name her own intestines or esophagus, it is by way of others’ gaze that the Summoner recognizes his appearance as frightful, symptomatic, and in need of alteration. What could have been a mere accidental quality, a reddened roughness of the skin, assumes the role of stigma. The friction that Chaucer famously evokes between each pilgrim’s social role and that role’s idiosyncratic performance becomes in the Summoner’s case a friction at his own bodily surface, between his materiality and his desires, between what others see and what he wishes them to see. It is a resistance that, one imagines, is perceptible in the medicated abrasion of his skin, raw with borax, mercury, lead, and brymstoon—a corroded redness that is finally inextricable from the symptoms he treats.

English Phisik

The sense that saucefleem’s remedies might be near at hand and bodily infirmity susceptible to medical know-how are hopes that Chaucer’s Summoner would have shared with many in late medieval England. Medical discourse was on the rise. In the later fourteenth century, readers began to seek out and produce unprecedented numbers of texts addressed to the tasks of understanding and caring for human bodies. England’s growing culture of medical literacy and care was in many ways unique—a bricolaged, miscellaneous, and constantly renegotiated set of practices.

The absence of even incipient structures of regulation and professionalization distinguished England’s medical marketplace from the contemporary situation elsewhere in western Europe. The Royal College of Physicians was not founded until 1518, and medieval Oxford and Cambridge had only paltry medical faculties: “At Oxford … fewer than 100 men left any record of medical study [before 1500]. This was about one percent of recorded students. Cambridge’s body of medical students was about half the size of Oxford’s.”29 This differed from the powerful medical faculties in Paris, Montpellier, Bologna, and Padua.30 England’s cities lacked the broadly organized medical guilds of a place like late medieval Florence, and none of them paid salaries to physicians to help the poor and sick, in contrast to France, Italy, and the Crown of Aragon.31 The lack of opportunities for official employment disincentivized medical credentialing. Instead, patients in England sought health care within a heterogeneous network of physicians, apothecaries, astrologers, members of barber-surgeon guilds, itinerant “leeches” with and without formal education, midwives, tooth-drawers, oculists, parish priests, monastic communities, saints’ shrines, and members of their own or local households. While a few shared assumptions about complexion and pharmacopoeia, based upon broadly Galenic foundations, lent consistency to this range of healing authority, there is little else that these several modes of care can be presumed to share.

And yet one finds evidence for marked, punctual growth in medical writing. Thousands of medical texts in Middle English and Anglo-Latin survive from the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.32 While many kinds of informational writing were on the rise in the period, “the greatest growth was seen in the number of medical and surgical texts written in medieval English. The increase was nothing less than explosive,” writes historian of medicine Faye Getz.33 The acceleration of textual production is evident in the calculations of Peter Murray Jones, based on Dorothea Waley Singer’s hand-list of scientific manuscripts in the British Isles from before the sixteenth century—which deals with an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 texts across several languages. Jones estimates that six times as many texts survive from the fifteenth century as do from the fourteenth—despite the falling population and the more ephemeral (because more utilitarian) manuscript formats. These numbers “argue sufficiently strongly for dramatic developments in the way medical and scientific books were valued and used.”34 Moreover, Jones’s analysis shows the strongly medical orientation of the developing interest in science: the sum of texts and manuscripts dealing with medicine “amounts to more than all those dealing with the remaining subjects.”35

The database of scientific and medical writings in Old and Middle English, compiled by Linda Voigts and Patricia Deery Kurtz, provides another window onto the remarkable growth of medieval English medical writing. In 1995, when the first iteration of the database was nearly complete, it included “records for approximately 7,700 witnesses to texts, of which two hundred are Old English and the rest Middle English.”36 When the CD-ROM version of the database was issued five years later, it contained entries from 1,200 manuscripts.37 A search of the updated and revised version, made available online in 2014, turns up 7,048 scientific and medical texts when sixteenth-and seventeenth-century witnesses, as well as Old English texts, are omitted.38 Not all of this enormous number are medical, but the majority are, falling under such indexed subject categories as medical recipe-collections (1,926 records), herbs and herbal medicine (624), urine and uroscopy (459), bloodletting (408), humors (349), regimens of health (298), diet (274), gynecology and obstetrics (197), plague (174), etiology (146), and surgery (132). Other popular genres—works of alchemy, charms, aids to prognostication, astrological and calendrical texts, and veterinary medicine—often overlapped phisik’s concerns, aided in its practice, or shared its ways of perceiving and interacting with the material world.

Chapter 2 continues these reflections of the expansion of Middle English medical writing, but one point bears emphasizing in the meantime. Anglo-Latin medical writing also flourished during the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Though exact figures are wanting, it is clear that England’s Latin medical corpus grew in absolute terms, even if it declined as a proportion of all medical and scientific writing.39 In an earlier study, Voigts examined 117 medical and medical-scientific manuscripts (or discrete booklets) from late medieval England. Of these, only 30, or about a quarter, are entirely in Middle English; the rest are either entirely in Latin (16 manuscripts) or partly so (71 manuscripts).40 Thus the uptick in scholarly resources devoted to Middle English medicine should not obscure the reality that Latin and especially macaronic medical texts flourished at the same time. Latin works often appeared in the same codices as Middle English ones or in identical textual formats. No straightforward differentiation in audience was indicated solely by the choice of Latin or English.

The best name for this freshly textualized, decentralized discourse of medicine is phisik, a Middle English word that became prevalent just as the increase in medical writing was underway. Phisik sediments in its etymological history two successive developments in the medieval history of medicine: what might be called healing’s intellectualization and its subsequent popularization. The intellectualization began in the late eleventh century with the Latin term physica.41 In classical Latin physica denoted the branch of philosophy concerned with the natural world, deriving from physis, the Greek term for (roughly) “nature.” As classical natural philosophy, physica encompassed all inquiry into the qualities and operations of the mobile universe. During the Middle Ages, however, it took on a new meaning. As new Latin translations of Greco-Arabic medical writings began circulating first in southern Italy and then the rest of Europe, physica came to function as an alternative for the Latin term medicina, derived from the verb medeor, mederi—to heal or cure. To call medicine physica was to make claims about the rational character of medical knowledge—that it concerned fundamentally philosophical questions about what causes bodies to be as they are and to change. These are questions concerning the general order of nature, its categories and regularities. Physica in its medical sense, then, was inquiry into the human body insofar as the body was part of the orderly, rule-bound cosmos.

This sense of physica gained intellectual prominence in western Christendom through projects of translation, commentary, and teaching.42 Constantine the African (d. c. 1099) was the first major translator of Arabic medical writings into Latin. Working in the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, he translated what would become some of the most widespread texts of medieval rational medicine, including the Isagoge of Joannitius, the Viaticum (based on a treatise by Ibn al-Jazzar, d. c. 979), and the Pantegni (from the compendium by Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Majusi, d. 994). By the 1130s, Constantine’s translations are recorded in England. At the nearby “school” of Salerno, the Isagoge became a foundational text in the medical curriculum and so part of the articella, the collection of texts that would serve as the basis of medical teaching in Europe until the sixteenth century. Meanwhile, the labor of scientific translation picked up steam elsewhere in Europe. Gerard of Cremona (d. 1187), working in Toledo, translated inter alia several works of Galen and the very influential Canon on Medicine by Avicenna (Ibn Sina, d. 1037).43 Burgundio of Pisa (d. 1193) produced perhaps ten translations of Galenic treatises from Greek.44 As Michael McVaugh observes, the wealth of translations was such that by the latter half of the thirteenth century, “it was no longer possible to assume that a scholar could easily search out whatever text he might happen to want,” and ingenious précis and concordances, adapting developments in biblical scholarship, began to be devised, so that (in the words of one of these précis-makers, John de Saint-Amand) “students who pass sleepless nights looking for information among the works of Galen may be relieved of their struggles.”45 Medicina was established as one of the three higher faculties at medieval universities, and elite physicians and surgeons across Europe began composing “a newly self-conscious medical literature” of their own.46 Centers of medical learning took root in Montpellier and Paris in the late twelfth century and in Bologna in the early thirteenth.

The art of healing, then, had become a full-blown intellectual discipline. Thanks to the prominence of Aristotelian philosophy in the thirteenth century, the sense of natural philosophy as a science whose principal end was truth rather than practical action gained ground. But if medicina and scientia naturalis came to be defined against one another in this way, physica could still name their overlap in the newly rational medicine. And that systematic knowledge reached new audiences in formats like encyclopedias, how-to manuals, sermons, vernacular translations, miracle collections, and poetry.

When phisik became part of the standard vocabulary of Middle English in the fourteenth century, it did so in tandem with the remarkable upsurge in medical writing. While phisik maintained some of the bookish and philosophical associations of its Latin cognate, its semantic range also broadened and loosened. It continued to denote natural philosophy, as physica had in classical Latin, as well as medical science, as it had come to do in medieval Latin. Yet it also designated the medical profession, a medicinal substance, a medical treatment, a healthy practice, and a healthful regimen.47 It was sometimes used in contradistinction to surgery, which was understood to be a manual craft and therefore lower in the hierarchy of arts. Yet the mildness of phisik’s academic connotations is clear from its ready exchangeability with the originally Anglo-Saxon (and therefore markedly non-Latinate) term leechcraft. For instance, a translation of Guy de Chauliac speaks of the body’s role in “alle lechecrafte or phisic,” and John Paston complains about the cost of “my lechecrafte and fesyk.”48 The banns advertising a fifteenth-century medical practitioner proclaim, “Here is a man that is a conyng [knowledgeable] man in leche-craftis, bothyn in ffysykke & surgere.”49 Rather than marking a strong distinction between vernacular handicraft and Latinate science, phisik was an index of their overlap. If, in the two centuries preceding, physica had fitted healing to the systemicity of scholastic education, Middle English phisik adapted those academic ambitions to the decidedly unsystematic conditions of learning outside universities—and to the hopes for health that various categories of readers harbored.

The messy, makeshift, and profoundly generative labors of medical writing undertaken in late medieval England answered to two overarching purposes: the organization of information and the social accommodation of suffering. Medicine was simultaneously a system for explaining the entanglement of bodies in the material world and a set of techniques for managing that entanglement. “Iff mens bodies wern of irn [were made of iron],” speculates one work of Middle English medicine, “thei needen no rule of helth.”50 But human bodies were not iron. The remedy books so popular in the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were produced in and for communities that faced high levels of illness and infirmity. Nutrition and sanitation conditions contributed to the prevalence of diseases like tuberculosis, influenza, malaria, typhus, smallpox, and dysentery—to say nothing of the plague, which recurred periodically in England from the mid-fourteenth century to the seventeenth.51 Conditions like toothache, blindness, skin disease, paralysis, gout, kidney stones, and bone fractures further added to what Paul Slack calls the “burden of sickness,” or the costs imposed on a society by the poor health of its members.52 It is in light of such corporeal precarity that practices of vernacular medical learning took on their full significance. And it is against the shadowy background of the period’s largely unrecorded habitus of everyday embodiment—the lived varieties of physical care and embodied self-relation that were themselves reflective and imaginative undertakings—that medieval writings about the body should assume their meaning for us now.

The Body’s Causes

What models of embodiment did this newly accessible archive of theory-rich medical learning entail? Broadly based on the writings of Galen and his Arabic and Latin heirs, this system of ideas held that human physiology was made from the same components as the rest of the universe—namely, the elements (earth, water, air, and fire) endowed with their respective qualities (hot, cold, wet, and dry). The four bodily humors (black bile, phlegm, blood, and choler) were called the “children” of the elements, and they combined in each person to produce her unique complexion. Elements and humors could not be observed directly but they underlay observable things. Their qualities of heat and moisture did not merely differentiate the natural world but gave it its dynamism, drawing each element toward its proper place and in the process fueling physical change. The Middle Ages did not have an “ontological” concept of disease—that is, there was no entity, like a microorganism, that disease was understood to be—so medieval pathology dealt instead with the patterned conditions of the human body as the result of causal factors. A wide range of influences could affect an individual’s physiology—from the planets to daydreams, from the west wind to the scent of flowers, from sexual intercourse to the recitation of prayers. Not germs but the world itself “infected” the permeable microcosm.

The most common medical framework for explaining the hidden dimensions of the body was a triad of categories known as the “naturals,” the “contra-naturals,” and the “non-naturals” (res naturales, res contra natura, res non naturales). Ubiquitous across the medical corpus, this scheme provided countless thinkers with a ready means of thinking about somatic structure and alteration. Res naturales encompassed what was intrinsic to the body: “the elements, the mixture [of qualities] [commixtiones], the humors [compositiones], the members [of the body], the powers [virtutes], the faculties [operationes], and the spirits.”53 Contra-naturals opposed the health of the body; they were diseases and their symptoms. The non-naturals stood in between, neither good nor bad in themselves. They were the quotidian factors that influenced sickness and health: “The first is the air which surrounds the human body, [then] food and drink, exercise and rest, sleep and waking, fasting and fullness, and incidental conditions of the mind.”54 This widely known system propounded a model of corporeality as an amalgamated composite, knit together by the constant interchange of physical forces and stuffs. Bodily changes could be analyzed into a series of micro-events, each with its own contingencies. Imagining etiology might entail zooming in to the body’s constituents or zooming out to trace someone’s path through the world.

The Zodiac Man, a diagrammatic aid to bloodletting common in late medieval English manuscripts, offers an image of the body’s susceptibility to such a cause-struck world (Figure 2). The man’s naked body literally crawls with the symbols of the zodiac, representing the influence on various body parts of the moon’s path through the heavens. Painted in lavish color in many of the folded physicians’ calendars that were unique to late medieval England, the image was likely intended to be seen by patients and practitioners alike during consultations.55 Its effect, one imagines, was multivalent: bespeaking bodily vulnerability but also medicine’s learned mastery of that vulnerability; diagramming practical information while emblematizing, with strange acuity, the feeling of a body not quite under human control. Like the Wellcome Wound Man, the Zodiac Man is aesthetically arresting as well as informational. It suggests how newly accessible scientific information might have redounded on images of the body in an era when creaturely life was being reconceived within a web of material forces and technical explanations.

One particularly urgent occasion for etiological imagination was the Black Death. The epidemic ravaged Europe between 1348 and 1350, killing perhaps a third of England’s population in its course, with mortality rates much higher in some communities. A second massive outbreak hit in the early 1360s, and a total of thirteen epidemics on a national scale occurred in England between 1349 and 1485, along with numerous regional outbreaks.56 In the course of its devastation, the plague posed a number of etiological puzzles to medical thought.57 At least in its bubonic form, it was characterized by unusual and distinctive symptoms, reinforcing authorities’ sense that this was something new. Because it occurred in so many places at once, it could not be explained solely with reference to the elements and humors, nor on the basis of local environmental factors. Physicians agreed that it must have its origins in the heavens, in celestial events that could poison the atmosphere on such a vast scale. At the same time, differentiation in the plague’s effects also needed to be explained. After witnessing the first outbreak in England, the French physician and astrologer Geoffrey of Meaux announced his intentions “to write something about the cause of this general pestilence, showing its natural cause, and why it affected some countries more than others, and why within those countries it affected some cities and towns more than others, and why in one town it affected one street, and even one house, more than another, and why it affected nobles and gentry less than other people, and how long it will last.”58 To explain the plague, Geoffrey would need to grapple with causes at multiple scales, accounting for the disease’s massive reach as well as its variability across regions, between social groups, and even from household to household.

Figure 2. Zodiac Man. English, early fifteenth century. © The British Library Board, Sloane MS 2250, fol. 12.

An early and important attempt at explanation was undertaken in the shocking plague year of 1348. Writing at the behest of the French king, the medical faculty at the University of Paris located the disease’s “distant and first cause [remota et primeva causa]” in the astrological conjunction of three planets in 1345, which led to the poisoning of the atmosphere and to the corruption of susceptible bodies.59 The doctors enumerated other possible causes as well: winds blown from alien places, earthquakes releasing rotten vapors in the earth, unseasonable weather, and complexions that were especially hot and moist. This causal proliferation reflects the range of factors known to influence human sickness. It also registers the doctors’ uncertainty, “for a sure explanation [certa ratio] and perfect understanding [perfecta cognitio] of these matters is not always to be had.”60 The effort to reckon with an abundance of causes is entirely characteristic of late medieval etiological thought. In the first lines of their prologue, the physicians even pitch their report in terms of an idealized psychology of causal inquiry: “Seeing things which cannot be explained [effectibus quorum causa latet], even by the most gifted intellects, initially stirs the human mind to amazement; but after marveling, the prudent soul yields to its desire for understanding and, anxious for its perfection, strives with all its might to discover the causes of the amazing events [effectuum mirabilium causas].”61 This lofty philosophical opening should not, however, obscure the decidedly practical and social concerns motivating the king’s charge and the faculty’s recommendations for prevention and cure.

Between the mid-fourteenth century and 1500, 281 plague tractates are known to have been composed, typically explaining the causes of the disease and recommending a variety of precautions and treatments.62 Etiologically, most share the Parisian faculty’s tactics; they link the planets’ influence to the corruption of the air, while adding information about individual complexions and regimen, occasionally with a nod to God’s power.63 The genre was seized on by English readers. The tract of the otherwise unknown John of Burgundy (also called John of Bordeaux and John de la Barbe) was by far the most popular plague work in late medieval England. Probably compiled in 1365, it circulated in various Latin versions and gave rise to at least six independent Middle English translations.64 Something like forty-six witnesses to Middle English translations and adaptations survive from before 1500.65 As one Englishing explains, while the “influence or impressioun of the hevenly or high bodies” makes the air “corrupt” and “pestilencial in effect,” this environmental change is “nat al-only [not the only] cause of moreyne [plague].”66 The treatise cites Galen for the general principle that “the body suffrith no corrupcioun but if [unless] the matier of the body be prompt or redy.”67 So, it is not only the heavens above but flesh “stuffed ful of humours that bien [are] mystempered” that together create the conditions for plague.68

John of Burgundy’s treatise stresses the importance of the causal understanding it provides. For instance, in the words of the Middle English translation, whoever “han nat drunken of that sweete drynke of astronomy” will not be able to “put to this pestilencial sores no parfit remedy” because those who “knowe nat the cause and the qualite of the sikenes, they may not hele it, as saide the prince of medicyne, Avicen.”69 Averroes is also cited, with the Aristotelian truism that “a man knowith nat a thyng but if he knowe the cause both fer and nygh [distant and proximate].”70 In this vernacular rendering, such scholastic promotions of causational knowing reached new readers and charged etiological knowledge with the urgency of survival.

John of Burgundy’s treatise includes an acknowledgment of God’s power: whoever follows its advice may survive “if the helply [merciful] wil of God be with hym.”71 Likewise, the Parisian doctors duly state that “any pestilence proceeds from the divine will [epidimia aliquando a divina voluntate procedit].”72 Indeed, naturalist explanations did not contradict the supernatural etiologies that were ubiquitous in sermons and chronicles, where plague was cast as divine punishment for humankind’s sins. However, the intellectual energy of both the Parisian faculty and John of Burgundy was occupied with routing that ultimate divine cause through the intricate etiological apparatus of the physical world.

This emphasis on natural and especially astrological causation sometimes raised hackles, despite (or because of) its evident popularity. For instance, Dives and Pauper, a moderately popular Middle English dialogue on the Ten Commandments from the early fifteenth century, pushes back against naturalist presumption.73 In the section on the First Commandment, Dives mocks those who consider themselves astrological experts. They believe, he declares, “Noon hungyr [famine], noo moreyn [plague], noo tempest, noo sekenesse, noo werre [war] shal falle [befall]” unless caused by the heavenly bodies and predicted by the astrologers’ calculations—“for, as they seyn, the bodyis abovyn rewlyn [rule] alle thyngge here benethyn.”74 Such explanatory naturalists, according to Dives, make God “more thral [lowly] and of lesse power than ony kyng or lord is upon erthe.”75 Later, it is the remarkable diversity of natural phenomena that provides a further reason to doubt astrological causes—because, on this account, the planets cannot account for such variation. Ironically, Pauper’s description of the plague sounds at first very much like that of Geoffrey of Meaux:

Sumtyme is moreyn general, sumtyme parcyal, in on contree nought in anothir; sumtyme in on toun and nought in the nexte; sumtyme in the to syde of the strete and nought in the tothir. Sum houshold is takyt up al hool; at the nexte it takyt noon.76

[Sometimes plague is general, and sometimes partial, in one country and not in another; sometimes in one town and not in the next; sometimes on the near side of the street and not on the other side. Some household is completely devastated; at the next, no one is struck.]

Rather than pursuing an ever more intricate causal explanation to account for these variations (as Geoffrey of Meaux does), Dives and Pauper reject the utility of any such account and recommend turning to God instead.

Pauper prefers demons to celestial conjunctions as the intermediary explanation for pestilence: devils often “have leve [permission]” from God, for reason of “mannes synne,” to “doon [create] wondres, to causen hedows [terrible] tempest, to enfectyn and envenymen the eyr and causen moreyn [plague] and syknesse, hunger and droughte.”77 Strikingly, the dialogue even wades into the murky overlap between causation and semiotics. Pauper is eager to show that natural signs—especially the position of the planets—may signify without acting as causes. After all, he reasons, condensation on a stone “is tokene of reyn [rain]” but “nought cause of the reyn.”78 Just so, by means of the planets’ positions, someone gains knowledge not “as be [by] causis but as be tokenys, for God made hem to been tokenys to man, beste, bryd, fysh and othere creaturys.”79 Here is a passage of vernacular theory on the semiotics and etiology of the natural world.

As the example of Dives and Pauper suggests, medicine (together with natural philosophy) existed in a changeable, sometimes volatile relation with God’s omnipotence and the health of the soul. The impulse to regulate medicine’s and religion’s tangled jurisdictions is nowhere more evident than in the 1215 decree of the Fourth Lateran Council stating that “physicians of the body [medicis corporum]” must “warn and persuade” their patients “first of all to call in physicians of the soul [medicos animarum].”80 The statute justifies itself in terms of the well-being of patients: because “sickness of the body may sometimes be the result of sin [infirmitatis corporalis nonnumquam ex peccato proveniat],” it follows that once spiritual health (spirituali salute) has been seen to, patients “may respond better to medicine for their bodies; for when the cause ceases so does the effect [cum causa cessante cesset effectus].” Moreover, the writers explain, some patients, when their physicians advise them “to arrange for the health of their souls, [they] fall into despair and the more readily incur the danger of death.”81 Yet if all physicians did this, there would be no reason for fear. A final sentence dispels any ambiguity about the relative claims of body and soul: “Since the soul is much more precious than the body, we forbid any physician, under pain of anathema, to prescribe anything for the bodily health [pro corporali salute] of a sick person that may endanger his soul [in periculum animae convertatur].”82 The Lateran rule was often quoted or paraphrased in later texts, including medical ones.83

This decree was issued amid tensions concerning the role of Aristotelian philosophy in scriptural and moral matters. In no uncertain terms, the rule about physician of the soul takes the moralists’ side in seeking to subordinate naturalistic concerns to spiritual ones. Importantly, however, it leaves room for debate about causation. Bodily sickness is only sometimes (nonnumquam) the result of sin, which means that humoral, astrological, and other natural forces remain explanations circulating uneasily alongside moral and divine ones. This unsettledness necessitates the ongoing work of causal discernment and etiological narration. Given the ceaseless negotiation between medicine and religion throughout the Middle Ages, it is notable that Darrel Amundsen has found a close predecessor for the 1215 decree, in a twelfth-century medical treatise on physicians’ etiquette. It advises the physician to send his patient to confession before commencing any examination, because if the patient “hears mention of this [confession] after you have examined him and have considered the signs of disease, he will begin to despair of recovery, because he will think you despair of it too.”84 The Lateran decree offers an identical version of patient psychology; a recommendation for confession in the course of treatment makes the patient despair, perhaps fatally. In the overlap of these two documents, one sees medici of body and soul worrying, in almost identical terms, over how the sick will navigate the crisscrossing urgencies of physical and sacramental care.

When, in the General Prologue of the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer sketches his archetypical member of the medical profession, he makes explicit reference to etiology. The portrait of the “Doctour of Phisik” marks the close relation between medical skill and the knowledge of causes:

He knew the cause of everich maladye,

Were it of hoot, or coold, or moyste, or drye,

And where they engendred, and of what humour.

He was a verray, parfit praktisour:

The cause yknowe, and of his harm the roote,

Anon he yaf the sike man his boote.85

[He knew the cause of every disease, whether it was hot, cold, moist, or dry, and where they were engendered, and from what humor. He was a true and perfect practitioner: having learned the cause and the root of the harm, he soon gave the sick man his remedy.]

Etiological know-how is tied directly to the physician’s success in healing. According to the verses, identifying the “cause” of every illness means being able to place it within the system of elemental qualities at the foundation of medieval pathology. Although the basis of the Galenic system in the four qualities may seem simple, the portrait emphasizes the elaborate learning that makes such explanation possible. The narrator lists a rather staggering library of medical authorities that the Physician “wel knew” (lines 429–34), and also mentions his expertise in surgery, astrology, and the crafting of measured regimens. It is the fact that his treatments are informed by etiological acumen that makes the Doctour “a verray, parfit praktisour”: because he understands the cause and “roote” of the patient’s “harm,” he is able to give the “sike man” the proper remedy.

Yet the narrator’s famously offhand comment that the Doctour of Phisik’s “studie was but litel on the Bible” also suggests a limit to the physician’s explanatory authority. His current journey to the shrine of the “hooly blisful martir” who “hath holpen [has helped]” pilgrims “whan that they were seeke [sick]” gently qualifies the practical effectiveness of his remedies.86 The shrine was famous for its curative properties, and many of the ampullae that pilgrims used to collect holy water, which was supposedly tinctured with Saint Thomas’s blood, bear the words Optimus egrorum medicus fit Toma Bonorum, or “Thomas is the best doctor of the worthy sick.” The Doctour of Phisik may be a master of some causes but ignorant of others. In the Middle Ages there was no a priori principle to guarantee that a naturalistic explanation for health was more appropriate than a supernatural one, or vice versa.87 The controversy that the Physician has inspired among modern readers—does Chaucer portray him as laudable or blameworthy?88—reflects what was an open question in the later Middle Ages. How legitimate was it to bracket the Bible and concentrate on the intricate technicalities of the medical arts? Chaucer’s portrait implies at once the height of the Physician’s learned authority and its provisionality within the wider frame of the Canterbury pilgrimage and the Christian cosmos. The narrator’s lightness of touch in evoking both medical authority and its limits suggests something of the undecidability of religion’s and medicine’s claims on the body.

The “Specific Rationality” of Medicine

Medieval medicine’s special relation to etiology stemmed not only from the vast number of physical causes it sought to comprehend. It arose as well from the unique position of phisik among medieval discourses of knowledge. More than any other, medicine was aware of itself as an amalgam of theoretical and practical expertise and sensitive to the fact that this produced its “specific rationality,” or its logic and style of thought.89 The standard primer in medieval medical education, the Isagoge, opens by stating that “Medicine is divided into two parts, namely, the theoretical and the practical [Medicina dividitur in duas partes, scil. in theoricam et practicam].”90 Similarly, Avicenna, at the start of his influential Canon, explains medicine’s division into theory and practice: “Theory is that which, when mastered, gives us a certain knowledge, apart from any question of treatment. Thus we say there are three forms of fever and nine complexions. The practice of medicine is not the work which the physician carries out, but is that branch of medical knowledge which, when acquired, enables one to form an opinion upon which to base the proper plan of treatment.”91 Almost all systematic treatments of medicine begin by dividing medical learning into theory and practice. In doing so, writers flagged medicine’s special responsibility to hold together generality and particularity, philosophy and experience, and universal principles and individual cases.

The epistemological status of medicine was of special concern in the Middle Ages thanks to Aristotelian hierarchies of knowledge. Writing in the early eleventh century, Avicenna was already anxious to synthesize Galenic and Aristotelian systems. That task became urgent for medical thinkers in western Christendom following the ascent of the “new” Aristotle in the thirteenth century. At stake was the standing of medicina in the emerging culture of the university. In the hierarchies that structured academic learning, the more that a discipline mixed in the realm of contingent particulars, the lower its status was on the scale of intellectual value. In accord with Aristotle, thinkers tended to doubt that real truths could be based on particular experiences of an ever-changing physical world. Such observations lacked the necessity and universality proper to scientia, which depended on a rigorous demonstration through deductive process beginning with first principles and definitions.92 Medicine sat uneasily astride the definitions of scientia and ars. It was both a theoretical discipline with its own principles and a practical discipline proceeding by empirical observation and inductive judgment and aiming to affect patients’ health.

Uneasiness about medicine’s epistemological status is nowhere more visible than in the scholastic prologues, or accessus, of medical treatises, which became increasingly elaborate as writers sought to describe medicine in Aristotelian terms.93 There, medical writers questioned whether medicine was a scientia or an ars; if a scientia, whether it was speculative, practical, operative, active, or mechanical; if an ars, whether it was mechanical or “real” (realis); whether it was the most perfect art; and so on.94 Most agreed that to the extent that medical thought moved from causes to effects, it, like natural philosophy, possessed demonstrably true knowledge based on axiomatic principles—and was thus a scientia. But to the extent that the physician tried to infer causes from observable effects and to read etiologies from symptoms, medicine was far from a pure science. Among the medieval disciplines of understanding, then, medicine played fretfully between causes and effects.

Such considerations did not remain confined to academic prefaces. The innovative French surgeon Henri de Mondeville (d. 1316) negotiated medicine’s double role in his Chirurgia.95 On the one hand, Henri was eager to dismiss mere empiricism. Speaking of the necessity of theory and abstraction, he warns that “particular cases are and always will be infinite in number, and consequently unknown [quia particularia sunt et erunt infinita et per consequens ignota].”96 And yet, he points out soon after, in a warning against overly abstract theory, “medicine is carried out not on mankind in general, but on every individual in particular [medicina enim non fit homini in universali, sed unicuique individuo].”97 Traces of similar oscillation and compromise are evident even in Galen’s writings, composed in what was already an Aristotelian age. The Greek physician’s disagreements with both sides of his era’s polarized medical culture, the medical “rationalists” and “empiricists,” show him trying to balance the sure knowledge of natural philosophy against the insights of sensory observation and experience.

A related epistemological point is made in no less prominent a place than the beginning of the Metaphysics, where Aristotle states that it is a matter of experience (experientia) “to have a judgment that when Callias was ill of this disease, this did him good, and similarly in the case of Socrates, and so in many individual cases.” However, it is a matter of art (ars) to judge that the treatment “has done good to all persons of a certain constitution.”98 While art is a higher form of knowledge than experience, the imperatives of clinical treatment appear to upend the hierarchy:

For the physician [medicans] does not cure “man,” except in an incidental way [secundum accidens]—but rather Callias or Socrates or someone else called by some such individual name, who just happens to be a man [cui esse hominem accidit]. If, then, someone has the explanation [rationem] without the experience [sine experimento], and recognizes the universal [universale] but does not know the individual [singulare] included in this, he will often fail to cure [curatione peccabit]; for it is the individual that is to be cured [singulare namque magis curabile est].99

This passage should not be taken as a defense of empiricism. Aristotle leaves no doubt that wisdom comes with explaining the causes behind observed facts. But the passage distances such wisdom from practical success. Because healing is a matter of particulars, of this embodied individual, experience might prove superior. While treating the patient as “man” may be essential to medicine’s scientific project, it is a particularized person, designated here by the proper names Callias and Socrates, who wants healing. The passage captures something of the epistemological pathos of medieval medicine, as it weaves from general knowledge to singular scenes of suffering and care, and back again. The flickering between generality and particularity is what the Wellcome Wound Man (discussed at this chapter’s opening) likewise sets in motion—as the image’s diagrammatic universality warps but does not subsume the individuality of the man’s figure and face.

Joel Kaye’s magisterial study of the new “idea of balance” arising between 1250 and 1375 locates medicine at the heart of scholastic intellectual history, despite what would seem to be its problematically practical focus. Kaye’s book follows the vicissitudes of a conceptual model, that of “equalization,” as it was gradually developed and disseminated in scholastic thought. This wide-ranging paradigm, based partly on Galen’s ever self-calibrating body, focuses on the “dynamic interaction” of a system’s working parts and the production of balance as the “aggregate product of the systematic interaction of multiple moving parts within the whole.”100 This model “made possible a form of naturalistic explanation that did not require the existence or intervention of an intelligence or ordering power existing above or outside the sphere that it governed.”101 In other words, the interaction of causal forces themselves produced the qualitative identity of the system in which they participated. Though Aristotle had an intellectual cachet with which scholastic thinkers were eager to associate themselves, Kaye argues that it was Galenic thought that actually acted as a crucial, if partly disavowed, intellectual model: “While the writings of Aristotle are generally taken as the textual point of departure for scholastic speculation, I have found that the most dynamic and productive texts behind the new model of equilibrium came not from Aristotle but from Galen and his continuators, both Arabic and Latin.”102

Symptomatic Subjects picks up where Kaye’s study concludes. In the later fourteenth century, according to Kaye, the scholastic model of equilibrium broke down. He hazards two speculations as to why. The first is the development of a “plethora of competing models,” which dispersed the paradigms’s coherence just as “the university ceased to be the center and arbiter of speculation.”103 The phenomenon of explanatory proliferation, which accompanies the diffusion of intellectual authority beyond the university, creates the conditions of etiological imagination to which I have gestured, especially among lay and vernacular audiences. The second reason Kaye hazards for the breakdown of the scholastic model of equilibrium is what he describes as the widespread “failure of faith in the potential of systematic self-ordering and self-equalization: a failure in the assumption that the process of interior self-ordering can, in itself, replace the ordering power of an intervening or overarching intelligence.”104 Indeed, such distrust in systematic self-balancing is found frequently in the sources discussed in the ensuing chapters of this study, whether in the physician Arnau of Vilanova’s worry over medical contingency or in Arcite’s corrupting body in Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale.”

Behind such pessimism, Kaye speculates cautiously, may be all the bad news of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—plague, labor unrest, authoritarian politics, heterodoxy and its suppression. Yet, I think, just as important to the pessimism expressed in my sources is these sources’ scale. Both practical medicine and imaginative literature tend to think at the scale of the individual. If natural philosophy and avowedly theoretical medicine concentrate on the regularities of the species, medical practice and literary narrative proceed from the exigencies of individuals. It is “the individual that is to be cured,” as Aristotle writes, and it is also the individual who perishes, as all eventually do. The model of equilibrium that Kaye so persuasively identifies does, I think, find its way into the late medieval milieu of phisik—but as something fragilized and perhaps faulty. The self-equalizing model is the occasion for intellectual experimentation in various texts, as the body’s causal determinants are imagined and reimagined. But the numerousness of the factors involved tends to overwhelm powers of comprehension and control. After all, embodiment always turns out to be terminal.

Medicine’s position between theory and practice, between universal and particular, draws it into close alignment with two other intellectual procedures, narration and exemplification. As the causal forces understood to structure the physical world became more multifarious in the later Middle Ages, the task of interpreting individual bodies became more delicate.105 It required picking out the relevant threads of explanation and then charting singular itineraries of implication and consequence. This often happened through narrative, the efficacy of which was increasingly recognized in contemporary trends in academic medical writing.106 Experimenta, or “case histories,” and consilia, or didactic accounts of cases, became increasingly important genres for late medieval physicians and surgeons, as they responded to the perceived inadequacies of systematic theorization.107 Moreover, to put medical principles into action, practitioners had to recognize patients as examples, by discovering each body under examination as an instance of broader medical categories, and so to bring that individual, here and now, into the medicine’s system of interpretation.

Late medieval medicine, then, shares with practices of medieval narrative a vivid interest in the exemplary and explanatory functions of individual bodies. This fascination, with how general principles and overarching laws might (or might not) be legible in the flesh, animates an extraordinary passage from a mid-fourteenth-century devotional work. Henry of Lancaster’s (d. 1361) Anglo-Norman Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines (The Book of Holy Medicines) consistently imagines penitential spirituality through a series of intricately physicalized images of wounds, sickness, treatment, and healing. In this passage, however, his meditations turn to a body marked by learned medicine in particular. Henry prays:

Most sweet Lord, I entreat you that it please you that I may then be cut up and opened up before you [defait et overt par devant vous], my Lord and my master, as certain people are before the surgeons at those schools in Montpellier and elsewhere [devant ces surgens qe sont a ces escoles de Monpelers et aillours], to whom is given a man lawfully executed [mort par le droit de juggement]; he is given to them to open [est donee pur overir], in order to see and understand how and in what fashion the veins, nerves, and other parts are disposed in a man [a veoir et conoistre coment les veynes, les nerfs et les autres choses gisent dedeinz un homme et la manere]. Sweet Lord, I should wish to be opened up like this before you, that you might see fully openly how my flesh and my veins and all my limbs are suffused with sin [tout en apert veoir coment ma char et mes veynes et touz mes menbres sont pleyns de pecchés]; not at all, Lord, because I do not know full well that there is nothing you do not know; but to be healed of my evil illness [mes pur estre garry de ma male maladie]. Furthermore, I am a man condemned to death by law for my crimes, so that you can, Lord, with good reason, open and cut me up rather than another, and make an example of me to others so that they may see and recognize the abscesses in me [pur ensample doner de moi as autres des enpostumes q’ils purront veoir et conoistre en moi].108