Читать книгу A Song for Jenny: A Mother's Story of Love and Loss - Julie Nicholson - Страница 7

CHAPTER 2 Prelude

ОглавлениеTears, idle tears, I know not what they mean, Tears from the depth of some divine despair Rise in the heart, and gather to the eyes, In looking at the happy autumn-fields, And thinking of the days that are no more.

TENNYSON

Bangor station is more or less deserted; there’s only a smattering of people, holidaymakers I guess from the chatter and clothing and luggage. One or two faces glance at me as I pass along the platform: another holidaymaker in her linen trousers, summer top and flip flops. People smile and nod good morning. I half smile back. There’s a family group with three young children, slightly old-fashioned looking, carrying buckets and spades and dressed in knitted cardigans over shorts and T-shirts. I listen to their sing-song chatter, parents, grandparents and children, light-hearted and joyous. The smallest child is wearing red wellington boots and jumping up and down in excitement as the train approaches. The granny takes her hand as the men pick up the luggage and my mobile phone bleeps in my pocket.

A text from Vanda: ‘are you on the train yet?’

I wait until I’m settled in a seat – plenty to choose from – before replying and also sending a text to Sharon letting her know I’m on my way. She sends one back almost immediately saying ‘see you soon’. People have stopped asking if there’s any news.

As the train trundles out of Bangor station I notice the happy holiday family have settled themselves further down the carriage. I’m glad of the distance and the peace and quiet.

It’s a fairly grotty train, old bucket-type seats, upholstery worn thin and shiny, windows darkened by dust and grime. Still, I can see out. The train picks up speed and soon we’re speeding along the North Wales coast. The sun is rising in the sky, bathing the mountains in early morning glow and causing the sea to shimmer – so beautiful, so tranquil, and so perfect. We pass through one seaside town after another, Conwy, Llandudno, Colwyn Bay, Rhyl, and I watch, hypnotized, as other passengers come and go. The train carries me along, eyes unwavering, fixed on the distance, staring out at the horizon, on and on through mile upon mile of early-morning glistening coastline.

When the train stops at Llandudno Junction a young couple laden down with climbing gear pass by my window. Laughingly they heave rucksacks on to their backs and set off in a joyous mood, hand in hand.

Leaving Anglesey behind exposes a trail of memories of other summers spent watching the happy, laughing faces of my children and nieces and nephews as they scrambled over rocks and enjoyed the freedom of the beach. Memories of wonderful, fun-filled times and of fallouts when family gathered together and inhabited the same small space; of my mother-in-law shouting at careless boat-handlers who leave trailers lying on the beach for little feet to trip over; of endless days spent waiting for the rain to cease and games of Trivial Pursuit with laughter-filled accusations of cheating and red-herring clues; impressive thunder and lightning storms over the bay; a star-filled midnight sky; quiet, tranquil out-of-season days; and noisy, crowded peak-season weekends with a bay full of motor boats and jet skis jamming the approach lane with four-wheel drives and trailers.

I remember the moment I first felt Jenny’s life within me. Of course I didn’t know it was Jenny then; it could have been Isabel or Christopher or one of my favourite Shakespearean heroines Hermione.

I am in the tiny bay of Traeth Bychan on the island of Anglesey where the Nicholson clan has gathered for the spring bank holiday weekend. Some of us are braving the still wintry temperature of the sea for the first swim of the season. Greg has plunged straight in, strong front crawl strokes taking him away from the shore without a backward glance until he is far out and then he turns, calling to the shore, ‘Come on’. My arms are raised in the brace position as the ice cold water laps over my feet, knees and up to my thighs. Counting one, two, three I plunge into the sea, teeth chattering, breathless with cold. After a few strokes I’m used to the water and shout encouragingly at someone still tentatively wading through the shallows, ‘It’s wonderful once you’re in’.

Wonderful it may be, but too cold for more than a quick swim. Before long, I’m picking my way carefully back over the stones and pebbles that separate the sea from the low prom wall surrounding the bungalow and old smithy, two buildings which form the family holiday home. My mother-in-law, already changed from her swim into shorts and a top, is waiting with a mug of coffee as I step over the wall onto the prom. Wet springy curls frame her face as she settles into a deckchair with her own coffee and takes a furtive puff from the cigarette that she thinks no one can see her smoking. Her perpetually bronzed limbs glisten with newly applied olive oil as she raises her feet to the wall for another coating of sun. This place has been her holiday home since she was a child, the place where year after year, at every opportunity, she has brought her own children and now an emerging new generation of grandchildren. Already there are three, Lucy and Andrew and baby Katie, with the next baby on the way as I am pregnant, barely five months.

Wrapping a towel around my wet and shivering body I drink from the mug of coffee before donning sunglasses, spreading the towel on the ground and settling down to dry off in the sun with a book at the ready. Other members of the family return from their swim and are soon scattered around the prom lazing, like me, on towels reading or dozing or sitting in chairs gazing out to sea. A few small sailing dinghies bob about in the bay and other larger sailing boats are dotted around further out to sea. It is quiet and peaceful in the early season and the entire bay seems to belong to us. As I turn page after page, words fade in and out of focus and I soon give in to warmth-induced sleepiness, resting my head on the open book and closing my eyes. There is barely a sound other than the distant passing whir of a speed boat, an occasional call of a child and the gentle afternoon drone of the corporate Nicholson snore. All is still and in the stillness I feel a tiny movement in my womb, like a flutter of butterfly wings. I hold my breath and wait; there it is again, another butterfly movement. For a few minutes I lie secretly revelling in the new sensation before lifting my head and saying, ‘I just felt the baby move’.

Turning over onto my back, placing my hands on the spot where I felt the tiny flutters of movement, an instinctive gesture of protection for the life within that has begun to make its presence felt.

Anglesey holds so much of the past, times to treasure and times lost. As the island recedes into the distance of the coast and into the distance of memory I’m surprised by an overwhelming feeling of sorrow and by the idea that I never want to return. My hands feel damp; I look down at them resting in my lap and notice a damp patch on my trousers. For one awful and embarrassing moment I think I’ve wet myself before realizing that my face is also moist. Instinctively, almost absently, I lift a hand to wipe away tears streaming down my face.

I don’t know how long I’ve been crying, yet not crying. No sound, just tears. How could I not have realized? Instinctively I glance around at the few people dotted around the carriage; no one is looking or taking any notice of the lone traveller staring through the window, lost in thought and crying her silent tears. Wiping my hands on a dry patch of trouser leg, I lean my head against the coolness of the glass window pane, aware but not caring about the sodden patch on my lap. Tears continue to flow and I let them fall, unchecked, on to the spreading wetness of darkening red linen, looking more like blood than water and feeling like the broken waters of impending childbirth. ‘Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean.’ Is this the difference between crying and weeping – sorrow rising from the heart, wordlessly and soundlessly?

Now I can’t bear my thoughts; they tumble out with my tears, images of Jenny lying hurt and afraid and alone. I screw my eyes up tight and lament with all my heart: Please God please God please God. Please God what? Keep her safe, keep her safe: words going round and round my head, picking up the age-old rhythm of the speeding train. I jump to my feet in a rising tide of panic, searching through my bag for a pack of tissues and blowing my nose fiercely to rid my head of wild unwanted thoughts and unuttered prayers. Groping for the sunglasses perched on top of my head I pull them down to shield my eyes, protection against more than the glare of the sun.

I try not to think of the last twenty hours or the implications of my journey but it’s impossible not to think of Jenny and I tell myself over and over again she’s going to be all right, she’s going to be all right, keeping my mind focused on that one positive thought.

The motion of the train is soothing and must have rocked me into a light doze. When I open my eyes we’ve left the coast behind, the landscape is duller, industrial and functional, more in keeping with my mood. The guard announces the approach to Crewe. Shrugging on my denim jacket and checking for the ticket in the pocket, I grab my bag, take a quick look around in case I’ve left anything, then walk along the carriage towards the nearest door, relieved that the first step of the journey is almost over.

I stand with my legs astride my bag and rocking from side to side with the motion of the train. Wales has merged into England and the past into the present. I try not to see the future looming darkly like the shadow currently spreading along the carriage as the train pulls into Crewe station.

I have to lean out of the window to manoeuvre the handle that opens the door, which jams and then swings open with such a force that I almost fall out. I head straight for the Ladies and check the pitiful state of my face. I repair the damage and then contemplate going to the buffet and having a cup of coffee but decide against it and sit on a bench to wait the half-hour or so for Sharon’s train.

More waiting! I sit very still, feeling quite composed, looking straight ahead and listening to station announcements, doors slamming and whistles being blown, sharp and piercing. A guard walks by and asks if I’m all right. Instead of answering I ask if this is the platform for the Manchester train.

‘You’re all right, love, about another twelve minutes now.’

‘Thank you.’

I smile to myself. Maybe he wasn’t asking after my wellbeing, merely enquiring if I needed any information.

A couple more trains pull in and pull out before the tannoy announces the arrival of the Manchester train. As the train pulls in I get to my feet, scanning the windows for a sign of my cousin; then as it stops I see her at the door directly in front of me. Dark brown hair frames her face on the other side of the window. She doesn’t see me at first. All her attention is on heaving down the window to lean out and open the door. Then just as I lift my hand to wave and attract her attention, she lifts her head, catches sight of me and smiles in recognition. My cousin Sharon, tall as I am short, colour co-ordinated and elegant even at this hour of the day, steps down from the train and we move towards each other, embracing, holding each other for a moment. No words are spoken, the hug says everything. As we move apart we both have tears in our eyes. There’s a while to wait for the connection so we sit in the buffet with a cup of coffee and catch up, talking calmly and concentrating on details and logistics and what we’ll do when we get to Reading.

There’s a man, smart, good-looking, youngish, in a seat across the aisle, travelling alone. He has a warm smile and confirms we’re on the London train as Sharon and I settle into our seats and dither about a bit, making sure we’re on the right train and that it stops at Rugby. He’s trying to get back to his family in London. He left home early yesterday, before the explosions, for a meeting in the North and because of the disruption of trains was unable to travel back yesterday evening. He has a wife and two little girls. We talk generally about the horrors of yesterday and then tell him the reason for our journey. He’s very concerned and attentive and kind. Talking to him helps; it gives us a sense of purpose and solidarity; it’s energizing somehow. We can be positive and say determinedly that Jenny appears to be missing, probably caught up in the chaos and we’re on our way to London to search for her. In less than an hour the train pulls into Rugby station and as we prepare to leave our travelling companion gives us his business card and asks if we can give him a quick call when we’ve found Jenny, to let him know how things are. As he hands me the card he says, ‘I’ll be thinking about you and hope you find your daughter safe and well. If there’s anything I can do, anything, please call.’ I want to hold the moment, give myself up to the reassurance of his caring presence and kind words, but we must be on our way and he must be on his.

Stepping down from the train we spot Martyn further along the platform, waiting and looking out for us. After quick hugs and greetings he takes our bags and we head towards the exit. Behind us carriage doors slam and a whistle blows before the train slowly starts to pull out of the station. As we reach the exit I catch a glimpse of the man inside a carriage, standing and looking out, his face no longer smiling but full of concern. He passes before my eyes, his arm raised in farewell.

Martyn and Sharon are talking. I turn my attention deliberately away from the departing train and follow my cousins to the car. Any awkwardness and emotion is alleviated through the chatter relaying details of the journey and the concern and kindness of the stranger who through a chance encounter did us a great service and, in doing so, made all the difference.

Time drags as we motor south. There are hold-ups on the motorway so we find an alternative route which takes us through villages and small towns. I can feel myself growing increasingly agitated as we hit one hold-up or roadwork after another. In distance we’re close to Reading yet in time so far away. Martyn estimates we’ll be an hour or so, later arriving than anticipated. It’s frustrating for all of us and all sorts of useless berating goes on in my head: We should have taken the train to Reading … We still have to get to London … I should have left Anglesey yesterday and ignored police advice … I should have travelled to Reading last night … I should be in London finding Jenny not held up by roadworks … I’m letting her down. Then I hear my grandfather’s voice piercing my memory: Don’t waste your time worrying about what you should have done – things are as they are.

At last we’re on the approach to Reading. We drive past the university and Elmhurst Road where Jenny spent her first undergraduate year in halls; then I phone James for directions to the house. James and Vanda come out as we pull up outside. As we pass through the front door I catch sight of Jenny’s black high-heel shoes, kicked off and lying abandoned. The sight of them is almost my undoing.

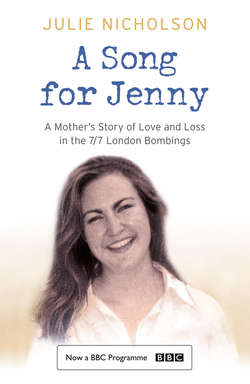

There isn’t time or opportunity to stop and ponder as we move on into the sitting room where my oldest friend Dendy, Jenny’s godmother, is sitting with a mug of tea, having travelled from Bristol by train earlier to help with the search. Over mugs of tea we talk about what to do. My sister Vanda is speaking, saying her husband Stefan has stayed home with their children but is concerned that we must have a plan and not wildly rush into London going randomly from place to place. I had thought we could split up into pairs and cover as many hospitals as possible in a short time but James, having been in London the night before, thought we should head straight for the Royal London Hospital as apparently that is where all survivors have been taken who were not yet accounted for. James has printed off a large picture of Jenny, taken outside the Albert Hall. It’s not one I’ve seen before; she looks beautiful, happy and laughing. He’s saying how people in London last night were handing out pictures of missing friends and family and thought it would be a good idea to take one of Jenny; someone may recognize her.

Should we go by train or car? Martyn volunteers to drive but there isn’t enough room for all of us and it doesn’t make sense to take more than one car. Stefan, practically, had thought there should be someone at the end of a phone, providing a kind of base camp and keeping in touch with Greg, Lizzie and Thomas. My sister makes a reluctant suggestion that she should withdraw from the search party and return home to be with Stefan, where they can be the conduit for news. I really want her to come with me but the fact is there isn’t room in the car for more than five people and someone has to stay behind. Vanda also has two young children to take care of. All things considered, this is the only sensible compromise. A decision has to be made and we need to get going. We agree to call every hour even if there’s no news.

My husband and two children are in Bristol, my parents in Anglesey and now I’m leaving my sister in Reading. Everything is starting to feel very fragmented but this isn’t the time for self-indulgent emotions; all I can think about is finding Jenny.

Sharon sits in front with Martyn and I sit in the back of the car with James and Dendy. James is very quiet, mostly looking out of the window as we travel along the motorway towards London. I need something to do and begin sending text messages to various people who won’t yet know about Jenny. Dendy suggests sending a block message but I can’t manage the technology so pass the mobile phone over to her. She asks me what I want to say. What do I say? ‘I’m on my way to London. Jenny appears to be missing following the explosions on the underground yesterday. I thought you would want to know. Julie’.

Conversation is mostly sporadic and light. Sometimes we even laugh. Martyn finds a packet of Minstrel sweets and passes them around. Ordinary things! There are long periods when very little is said as we are lost in our own thoughts, gazing out of the window or attending to text messages on mobiles.

Traffic slows to a crawl on the approach into London. We travel alongside a small white van on the inside lane for a while before picking up speed again and moving ahead. The driver is bobbing his head around, listening to music and tapping out the beat on the steering wheel, oblivious to being watched from the neighbouring car. He’s wearing green overalls; some kind of maintenance uniform, I suppose. We pass each other several times as traffic speeds up and slows down in alternate lanes.

I ask James about the photo of Jenny taken on the steps of the Albert Hall. They were going to a Proms concert. James points out that what you can’t see in the picture are Jenny’s feet which had been hurting from walking around all day. She had swapped her high heels for a pair of James’s trainers, several sizes too big.

Once in the thick of London traffic we debate a route to the hospital. None of us really has a clue and consider stopping to pick up a map. For a while we go with the general flow towards central London, stopping and starting and trying not to get impatient with the slow progress. There’s nothing around us that suggests anything of the carnage we were fixated upon yesterday, glued to our television screens. Everything looks as normal: roads full of traffic; people meandering along and rushing about; shops open; offices functioning. For those of us in the back of the car, there’s nothing to do but be patient and look out of the window. Stiff from sitting in one position I shuffle around a bit and stretch my neck, looking out through the glass roof of the car; it’s a Scenic, I think. For the first time I notice tops of buildings and comment that one can’t usually look up and out from the inside of a car and it’s a new and interesting perspective. For a few minutes the talk is all about the buildings we pass and the architecture – architecture, for God’s sake!

We pull up at some traffic lights and a police car draws alongside. Waiting for the lights to change, Martyn quickly winds down the window and asks the police officers for directions to the Royal London Hospital. The officer nearest to us asks why we want to get there, as though they can sense the urgency, and Martyn explains, indicating towards me in the back. ‘My cousin’s daughter is missing and we’re trying to find her.’ The officer turns slightly to glance at me, and then tells Martyn to follow them; they will guide us to the hospital. The lights change and the police car pulls in front of us, forging ahead through traffic and traffic signals with determined confidence and speed. At times Martyn can barely keep up, nervously pressing through a red light as the police car ignores the signal to stop. It all starts to feel bizarre and quite surreal, on the tail of a police car speeding through the streets of London – not so fast that it was dangerous, just fast enough to bring Martyn out in a cold sweat.

‘This feels all wrong,’ he says. ‘Every instinct in my body tells me to slow down when I see a police car, not speed up and definitely not to go through red lights!’

The police car is clearly doing its best to get us through the traffic and to the hospital as swiftly as possible. Despite the tension it’s impossible not to see the farcical side of this; ‘Jenny would find this hilariously funny, like something out of a Bond film,’ I say just as the police car indicates for us to pull over.

The police officer in the driving seat gets out and walks the few steps to our car. ‘We’re heading straight on now but if you turn into this road on the left it will take you down to the hospital. I hope you find your daughter.’ With that he was gone and in moments the police car had sped off without giving us any opportunity to find out their names or say more than a hasty ‘thank you’.

The hospital building is obscured by scaffolding and green mesh, which makes the entrance difficult to find at first. Martyn drops us off and then goes to find somewhere to park the car. Dendy goes with him. ‘Don’t wait,’ Martyn says. ‘We’ll come and find you.’ The remaining three of us stand and watch as he drives off down the street then we turn and enter through the double doors of the hospital.

1989

Jenny is about eight years old. I’m rushing around, getting ready to go out, typically late, as is my lift. It’s a warm early summer’s evening; the front door is open so air can circulate through the house. Greg is settling Thomas and Lizzie, reading a bedtime story. Jenny is playing in the garden, looking out for my lift.

‘She’s here, she’s here,’ Jenny calls out, my prompt to hastily kiss Thomas and Lizzie before running downstairs.

‘Go inside now,’ I say to Jenny, ‘Daddy will be running your bath soon.’ She’s jumping on and off the wall, over the rose bushes which are in full flower.

‘I want to wave bye-bye.’

‘All right, but I want to see you go inside and close the door before I leave.’

I wave a greeting to my friend sitting at the driver’s wheel. Jenny is wrapping her arms around my neck and giving me kisses, lots of them, before climbing back on the wall and jumping over a rose bush again.

‘Watch, Mummy.’

‘Be careful, if you fall you’ll hurt yourself. That rose bush is full of thorns.’

‘One more jump!’

I close the front gate behind me and sit in the car, waiting, slightly impatiently, for the final assault over the rose bush. Jenny is waving at the car as she jumps; this time falling in the bush. Leaping from the car I rush back into the garden and help her up. She is shaken and fighting back tears.

‘My leg hurts.’

‘You’re OK,’ I say, brushing her down and showing her a small graze just above her knee.

‘Look, it’s just a scratch. Ask Daddy to clean it in the bath. You’re lucky you didn’t get a thorn.’ Taking her by the hand, we get to the door as Greg is coming downstairs.

‘Can you see to Jenny’s leg, she scraped it on the rose bush? I need to go.’

Jenny gives me one more, slightly tearful, kiss before I close the door behind me and hurry back down the garden path. Apart from a few pangs of maternal guilt as we drive away from the house, I think no more about the incident.

‘I’m not sure about this,’ I say to my friend as we drive along. We’re on our way to a religious campaign, a Billy Graham event which I have been persuaded to attend.

‘You’ll be fine. You might even enjoy it.’

‘I suppose I ought to listen to Billy Graham once in my life, if only to say I’ve done it!’ It’s fair to say I’m curious about the impact his campaigns seem to be having. This one is called Mission England.

Stewards are enthusiastically directing people into specially erected marquees. Already I am feeling this is not where I want to be. Inside the tent, people are jostling for seats; excited anticipation seems to be the prevailing mood though there are plenty of tentative faces and baffled expressions. The sermon itself is being broadcast from London and transmitted onto large screens erected at the front of the tent. With as much of an open mind as I can muster I settle back to experience the phenomena of Billy Graham. On this occasion the good news of Jesus Christ is lost on me. It is all too much, too zealous. As people leave their seats and go forward at the speaker’s invitation, first steps to a new birth, I can only look on in wonder.

‘This is not for me,’ I say to my friend who is looking delightedly at what is happening at the front. I want to leave but dare not leave my seat. Most of my life I have attended church, found a resonance in ritual and sacred music and enjoyed the community of fellowship. The rhythm of the church year and Christian festivals is as much part of me as the seasons of the year. I love to hear the retelling of biblical stories and engage with the mystery and exploration of faith so I’m not quite sure why I find this so alienating.

I arrive home feeling completely overwhelmed by crusading Christianity, bemused by the response of the masses and for some inexplicable reason utterly depressed by the whole experience. I turn my key in the lock, glad to be home and looking forward to a cup of tea and bed.

Greg’s face is sombre and doesn’t respond at all when I say I think I’m going to become an atheist. Instead he greets me with the news that he has been in casualty all evening with Jennifer, the result of a long deep gash from the fall into the rose bush. The injury required several stitches and a tetanus booster. Feelings of shock, concern and guilt all tumble out at once as I rush upstairs to check Jenny is OK. Tentatively, so as not to wake her, I lift the covers and peer at the dressing covering her entire upper thigh. Thankfully, she is sleeping soundly and peacefully. I lean over and place a kiss full of love and apology on her forehead. Propped up on the bedside table is a colourful ‘Certificate of Bravery’ made out to Jennifer Nicholson and issued by staff at the hospital. Downstairs Greg tells me how, after I left, Jenny pulled her skirt up to check her sore leg and noticed the full extent of the injury. Our next-door neighbour was called in to sit with the younger children while Greg took Jenny to hospital.

‘Let Jenny tell you about it herself in the morning, she wants to surprise you and show off her stitches and the certificate. She was very brave.’

Ah well, I reason, as my head touches the pillow half an hour or so later, I suppose this is the stuff of childhood. It could have been worse.

The Royal London Hospital, early afternoon Friday 8 July

The reception area is crowded. Looking around there don’t seem to be any notices or indications of where we might go for specific information regarding the events of yesterday. We speak to a passing uniformed nurse but she isn’t able to help directly or know where we should go. She isn’t aware of this hospital being a centre for concerned relatives and suggests we enquire at Reception. So we stand in the queue for the general reception desk and wait our turn. The person at the desk can’t tell us anything either, but directs us to a waiting room in another part of the hospital which is being used, she believes, as a temporary incident room. Once or twice we manage to get lost en route until eventually we find a member of staff who accompanies us to the right floor, leading the way through a door where we’re plunged into a sea of confused and worried faces, all turning to look at the newcomers as we enter the room. It’s a montage of images and shapes, of tableaux and sounds; it’s a film set with actors dressed as officers and personnel: there’s a sari and several pairs of jeans in shades of blue denim; a diminutive, elderly nun dressed in traditional black habit and a young black-suited cleric, tall with a slightly stooped appearance, wearing glasses and a dog collar. He’s holding a half-eaten sandwich still in its plastic container. This is not real. This does not belong to my reality, to the quiet vigil of yesterday or the gently poignant journey along the coast.

There’s a round table in the corner with large flasks and trays of beakers, jugs of milk and bowls of sugar; teaspoons are scattered around the table and used sugar packets litter the surface. A seated area to the left is separated from the rest of the room by a sort of handrail barrier. Some people are sitting, talking to what I assume to be police or medical staff and others are standing around the room. Doors at the end lead out to a balcony where some people are smoking, others speaking into mobile phones. Now that we’re here we don’t quite know what to do. At one and the same time it is both reassuring and bewildering. Having arrived at the place we now find ourselves hovering on the edge of someone else’s drama. There’s chaos, bustle, noise, yet in the midst of it all there’s purpose and quiet calm amongst the gathered groups. There’s a couple standing to our right; the woman holds a picture of a younger woman in formal graduation robes and smiling out from the picture. I catch the woman’s eyes; they’re troubled and slightly desperate. For a second or two we connect and exchange a look born out of mutual understanding as something between a smile and a grimace passes between us.

Martyn and Dendy arrive, talking about where they parked the car, unsure whether it was a legal parking space. Martyn shrugs his shoulders: ‘I left a note of explanation on the windscreen and hope I don’t get clamped or towed away.’ The five of us are wondering what to do. Martyn goes off to see if he can find out anything and the rest of us stand around, taking in our surroundings. When Martyn returns a few minutes later, he is none the wiser. It looks as if there are personnel moving around the room and taking details from people, so we guess we have to wait our turn.

The nun and the cleric stand out amongst the groups of people as they don’t quite belong. I move out to the balcony, possibly to avoid contact. Their presence symbolises that all is not well. At this moment I need optimism and hope. The view is hardly soothing. I want green fields and trees and flowers, not concrete and bins and pipes. I find myself part of the other communing bodies, leaning over the balcony, speaking into mobile phones, connecting with home, feeding the same non-information. This is where I am, this is what I’m doing, this is what I know, this is what I don’t know. How are you? What are you doing? Words of love and encouragement exchanged and reinforced across the country and probably also across the world.

A few chairs are scattered around on the balcony, but there isn’t any room to sit down so we move inside and stand in a group talking and not talking and looking around, and looking lost and looking at other people looking lost. The young cleric approaches us tentatively, asking if we’ve had far to travel today. ‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, what difference does it make how far we’ve had to travel today?’ Thankfully the words never leave my mouth. He’s still clutching his sandwich pack as he comes out with one asinine phrase after another. I let the others respond while I look on barely listening; thinking, impatiently and ungraciously, that I wish he would just go away and leave us alone. We all stand there for a few minutes until the cleric runs out of things to say and we run out of responses. I know I should say something to ease his discomfort but can’t be bothered. I feel irritated that we have to be subjected to his helpless ministrations. ‘Is there anything I can get you?’

I want to shake him. Clearly at a loss, he shuffles awkwardly from foot to foot before suddenly thrusting out the remainder of his sandwich towards us and asking if any of us is hungry. For a moment the sandwich hovers between us like an embarrassing pause before we politely decline. I don’t know whether to laugh or scream. With a rush of words none of us catch clearly he waves the sandwich in the direction of the refreshment table, inviting us to help ourselves to tea or coffee and biscuits and hopes it isn’t long before we get some news. On that we’re all in agreement.

Martyn pours tea and coffee into a couple of plastic beakers as a man standing close to the table informs us that the coffee is cold and the tea stewed. Nevertheless we take our beakers and move to the far side of the room where some seats have become vacant. Martyn and James stand by the window as Dendy, Sharon and I sit in a line, turning our bodies slightly in towards each other so we can talk more easily.

‘You should have told him you’re a vicar,’ Sharon says teasingly.

Our three sets of eyes follow the cleric, still clutching his half-eaten sandwich and now talking to an older couple sitting a short distance away. We sip our tepid tea and watch his slow progress around the room, warming to him as he extends his arm and offers his sandwich again. Maybe there isn’t anything else he can offer.

‘I wish he’d just eat it!’ I blurt out.

‘Is he a chaplain?’ Sharon asks.

‘I don’t know; he didn’t introduce himself as a chaplain. I think if he was a chaplain he wouldn’t be quite so ill at ease.’

‘Maybe he’s from a local church wanting to help in some way. He seems out of his depth.’ Dendy makes a half-hearted attempt at being charitable.

We’re all out of our depth, I think, but don’t say.

I might have been friendlier towards the cleric but he reminds me of who I am and possibly of my own inadequacies in such a situation. With some consternation, I realise I do not wish to be reminded of my own vocational role. If I were in his shoes, I doubt I could offer people any more than a half-eaten sandwich, which is a troubling thought. I do not wish to be aligned with these two people. I am a mother, desperately searching for her child. I am Jenny’s mother. I am also a priest but at the moment I am embarrassed by the fact and I am struggling to see how the church has a place in this room.

Eventually someone comes and takes a few details: my name, Jenny’s name, her age, our relationship and establishes that I’m the next of kin. Between us James and I give the information asked for: any scars, distinguishing features, colour and length of hair … We trip over each other in our eagerness to provide any detail that could help identify Jenny. It doesn’t take long. All of us watch and listen intently to what the woman is saying. Apparently there are seven casualties in total in different parts of the hospital in various states and conditions and yet to be identified. It’s possible that Jenny could be one of them. She’ll be back as soon as she has some information. Meanwhile, we should help ourselves to tea and coffee or water. For a moment I think she’s going to tell us to make ourselves at home.

The elderly nun is moving around, gliding up to people and standing alongside for a while before moving on. People are trying to avoid catching her eye. As though she spots a new set of faces in the room she moves over towards us. ‘Keep her away from me,’ I appeal to Sharon and turn my body pointedly in Dendy’s direction, feigning a conversation. I listen to the nun talking to Sharon for what seems an age. She has a kindly, soft, prayer-like voice and Sharon is being very patient and gentle in her response. The nun has assumed Sharon is looking for her daughter. Perhaps I should engage but it’s all too much effort and I remain resolutely turned away. At this moment I don’t want the attention of chaplains or nuns or anything except action and people who will help me find Jennifer.

Martyn has wandered off in search of a loo and James has sat down in the vacant seat on the other side of Dendy. His head is bowed and he’s staring at his rucksack on the floor between his feet. He looks far away and tired and there’s something about his hunched shoulders that makes me want to stand up and shout: Won’t somebody help us please. Of course I don’t.

The room is becoming increasingly crowded; everyone is desperate for information and feeling the frustration of needing to be tolerant of a system and await developments. The room is airless. Even with the doors to the balcony wide open, there is hardly any air circulating and the heat is oppressive and uncomfortable. Some people are waving papers like fans to create streams of cooling air. Empty water bottles lie discarded, scattered around the room on tables and under chairs. Water jugs on the refreshment table are being emptied faster than volunteers can replenish them. People sporadically go over to the table and tip the jug as though expecting a stream of water to miraculously appear.

Another cleric comes into the room, bearing a tray filled with white plastic beakers. He’s tall and has an air of confidence and authority as he announces: ‘Iced water if anyone would like some.’ He doesn’t ask anyone about their journey or sympathize in pitying tones, he simply attends to a present need – thirst in a crowded hot hospital waiting room – making eye contact and smiling his care as he passes around beaker after beaker of refreshingly cold water. ‘That’s my kind of chaplain,’ I whisper in Sharon’s ear.

The nun remains by Sharon’s side, watching events and commenting from time to time on something in the room or an aspect of the day. It seems that having found a sympathetic ear she is loath to relinquish her attachment and is now reminiscing, ‘This reminds me of the war,’ describing clearing away rubble from the streets and finding people beneath and how the spirit amongst everyone was wonderful. I dare not catch Sharon’s eye.

Just as I think we can’t bear any more Second World War recollections, however kindly meant and gently shared, the female staff member calls my name and comes over, we hope with some information, and the nun slips away saying something about hoping for good news and very nice to meet and talk with us.

It emerges there’s a young white woman, unidentified, in IT, aged about thirty. ‘Let me see her.’ Either I didn’t say it or the member of staff didn’t hear me. There are two other women also in IT but neither match Jenny’s description. One is an older woman and the other Asian. There’s one woman who could be Jenny and that’s the possibility I hold on to. I don’t think about why she might be in IT. We describe Jenny again, going over details as requested, hair, eyes, height. She confirms what James has told us, that there is no point going to other hospitals as all casualties yet to be identified have been brought here. A police liaison service is being put in place through the hospital and so we’ll be amongst the first to have someone assigned to us. We’re assured that for the time being this is the best place to be.

As hard as it is – and it is hard – all we can do is wait, patiently. Restless and impotent, together with everyone else in the room, we give ourselves up to the process. The term ‘waiting room’ has taken on a new meaning.

Martyn goes off in search of sandwiches, supplies for the long haul, he says, even though none of us is interested in eating. It’s hot. I go out on to the balcony for some space and air and attend to the now regular ritual of checking messages and rigorously calling Jenny’s mobile, persistent in urging her to be safe and in contact. The latter feels like a salve to the implications of the last hour. Hang in there, Jenny, we’re on our way to you.

Leaning over the balcony rail, for a few minutes blotting out the crowded room, I gaze down at the concrete vista, as I call home imagining the scene with Greg and Lizzie and Thomas, frustratingly dependent on us for any morsel of news. I wish I had something positive to give them other than relaying bare facts and rigorously repeating the need to stay positive. A smile escapes at Lizzie’s affectionate description of Auntie Chris making them feel they weren’t quite so alone any more. She tells me of friends who had called and of Sharon and Mike’s older girls, Katie and Joanne, who are driving down from Manchester so they could all be together – cousins in solidarity. Lizzie’s voice, sounding wobbly yet so courageous, lingers in my ear as my eyes remain fixed and staring.

Take courage, soul. This is my prayer, all I can muster.

I feel suspended between endlessly blue sky above and grey unrelenting concrete below. One contradicts the other, like my head, full of opposing forces. When I speak to people I hear my voice reasoning positively full of hope. Yet in moments of isolation this deep, creeping fear almost overwhelms me. Ripples of it rise up threatening to break the surface and I have to take deep guttural breaths to force it back in place. I remain calm, but it is, in truth, a fearful calm. On my way back into the room I stop to speak to a couple who smiled and said hello as I passed earlier. We talk for a few minutes, sharing stories of the last twenty-four hours and sympathizing with each other. They hope I find my daughter. I hope they find their son. This is a very worrying time, we all agree. They seem very alone.

As the afternoon wears on more and more people arrive. All the cultures of the world seem to be gathered here, united in purpose, many carrying pictures of missing relatives. A Japanese couple struggle to make themselves understood. A group of young adults looking for a lost friend bring new energy into the room as they take up seats in the same area as us. Their chatter is a diversion and provides a new focus for a time.

The person who spoke to us earlier and took Jenny’s details comes back. The young woman in IT is not Jenny. They checked hair colouring and other features and distinguishing marks. I don’t know whether to be relieved or despondent. In desperation I ask about the remaining casualties in other parts of the hospital, any chance one of those could be Jenny? Even as I ask I know checks will already have been made. I can’t take my eyes off her face as she shakes her head slowly. ‘No, I’m sorry.’ For a moment or two we stand in awkward silence.

‘What happens now?’ Martyn’s voice cuts into the pause.

‘A police officer will be along shortly to speak to you and take things on from here.’

For some reason I find myself saying ‘thank you’ before sitting down and waiting for the next directive.

More cooled water is being circulated but we’re almost too tired and preoccupied to bother taking any. The plastic bag containing packs of sandwiches Martyn went out for earlier lies neglected at our feet, mostly untouched. For a while after the latest information none of us speaks; we focus instead on drab peeling paintwork, metal window frames, torn or worn patches on seats and our own private thoughts. I watch as James takes his mobile from a pocket to check a text and replace it without replying.

Heads turn in the direction of the door as two police officers come in. The officers pause for a moment, scanning the room, before reading out the names of two families. The rest of the room waits expectantly for a few minutes before returning to its mix of activity and contemplation.

A young woman in a light blue shirt stands just inside the doors and looks over towards us, raising her eyebrows to enquire, ‘Mrs Nicholson?’ She introduces herself as Joanne, a police liaison officer. She’s a similar age and colouring to Jenny. We follow her into another room, smaller with a few functional tables set against the wall and chairs pulled around. There are already two other families talking to police officers in their respective groups. Joanne apologizes for the cramped space as we settle ourselves into seats and make introductions. She’s warm and friendly. Forms are systematically filled in; we respond to question after question, while Joanne writes. Descriptions and details already given are gone over again in minute detail: position and size of scar, dental work, surgical procedures, height, and vital statistics – hip measurements, chest. ‘She has a wonderful bosom,’ I blurt out, aghast at myself and recognizing shock in the faces of my companions at my outrageous remark. ‘Well, she does!’ I persist with some embarrassment.

James tries to remember what Jenny was wearing when she left for work, whether her hair was tied up or loose, what kind of bag she was carrying and what personal possessions she had with her. Between us we rack our brains for any detail that may help locate and identify her. James recites the route Jenny would normally take to work, and the timings, the unlikelihood of her being at Edgware Road travelling in the direction of Paddington. ‘It doesn’t make sense,’ James insists over again. ‘Jen would be travelling away from Paddington not towards it.’ Joanne doesn’t have any answers; all she can do is collate as much information as possible about Jenny and all we can do is cooperate in the task.

The interview is difficult; it’s impossible not to listen to snatches of conversation from the two other interviews going on in the room at the same time, we’re all in such close proximity. None of us has the luxury of privacy.

Joanne asks about Jenny’s teeth, whether she had any significant dental treatment. ‘She doesn’t have any fillings,’ I say when Joanna’s pager bleeps and with a hasty ‘excuse me’ she leaves the room and we have no alternative but to sit and eavesdrop on what the other families in the room are saying.

On her return, Joanne explains how the police liaison service works. I feel considerable relief knowing that someone is going to be working alongside us, on our behalf, in finding Jenny.

‘Where are you going now: Reading or Bristol?’ she asks.

‘Reading for the time being.’ I give her my sister’s address and phone number, then we go back into the waiting room while Jo attends to some practicalities.

After the confined atmosphere of the interview room, the open and fresh air of the balcony is a welcome change. For a few minutes we discuss the various aspects of the interview before dispersing around the balcony busy with our mobile phones.

I hear my name called and swing around quickly, my eyes sweeping past Dendy and Sharon and James in different parts of the balcony before fixing on the person coming towards me. Would I consent to having my DNA taken?

Through a haze I’m aware of a small room, a swab and plastic tube. I think I open my mouth. It is said that children only ask questions they are ready to hear answers to. I do not ask any questions of the person taking my DNA.

It’s all over. Joanne tells us to go home. There’s nothing else we can do here. The police liaison service will take over all the groundwork now.

‘Will that be you?’ I ask.

Disappointment is reflected in all our faces as Joanne explains that as she is attached to London we will be assigned liaison officers from the Reading area. We’ve warmed to her and built up some trust and confidence with her.

‘When will we hear from someone?’

‘Soon, probably in the next few hours.’

As James takes her card and puts it in his wallet, the last words we hear from Jo are: ‘But if there’s anything I can do, please call me.’

We’re a subdued group retracing our steps down vaguely familiar stairs and corridors and leave the hospital through the same double doors that we entered several hours before, walking straight into the path of a man holding out his hand and begging for money. We’re taken aback and pause, rather than stop, for a moment and look at him as we pass. All I can do is shake my head limply in response to his extended hand. None of us is in the mood to hear his tale of woe, in fact we feel he should be ashamed of himself preying on vulnerable people coming out from the hospital. He doesn’t give up on us as easily as we give up on him, pushing his bike and pursuing us along the road. He continues following and calling out to us for some time before we turn the corner in our callous disregard.

Buildings have blotted out the sunshine and we walk the rest of the way to the car in shade. Double red lines follow the kerb around and I ask idly what they signify. Apparently they’re worse than double yellow lines. Drivers must not stop or park on them for any reason. There isn’t a vehicle in sight so the penalty must be harsh. As I follow the double red lines along the road, they seem to represent all the frustrations and ‘no go’ areas of the last twenty-four hours.

We don’t say much during the drive out of London. Sharon calls Vanda to let her know we’re on our way. Any more information can wait until we reach the house. The atmosphere in the car is pensive. The last couple of hours have been filled with words and now there’s nothing left to say. We’ve run out not only of words but of energy and purpose too. Martyn concentrates on driving and the rest of us sit slumped in the solitude of our own thoughts. Mine are brooding and as much as I try to push troubling imaginings to the back of my mind, to keep focused on Jenny and on positive possibilities, darker thoughts niggle away at the surface of my consciousness. This day has not ended; it has been a beginning, an introduction, like the prelude to an immense piece of music.